Hypertensive emergency

| Hypertensive emergency | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Malignant hypertension |

| |

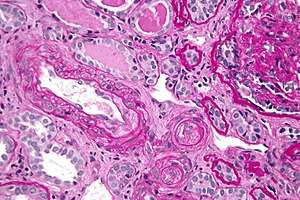

| Micrograph showing thrombotic microangiopathy, a histomorphologic finding seen in malignant hypertension. Kidney biopsy. PAS stain. | |

| Specialty |

Cardiology |

A hypertensive emergency, also known as malignant hypertension, is high blood pressure with potentially life-threatening symptoms and signs indicative of acute impairment of one or more organ systems (especially the central nervous system, cardiovascular system or the kidneys).[1] Typically the systolic blood pressure is at least over 180 mmHg or the diastolic is over 110-120 mmHg. It can result in irreversible organ damage. In a hypertensive emergency, the blood pressure should be slowly lowered over a period of minutes to hours with an antihypertensive agent.

Signs and symptoms

The eyes may show bleeding in the retina or an exudate. Papilledema must be present before a diagnosis of malignant hypertension can be made. The brain shows manifestations of increased pressure within the cranium, such as headache, nausea, vomiting, and/or subarachnoid or cerebral hemorrhage. Chest pain may occur due to increased workload on the heart resulting in a mismatch in the oxygen demand and supply to the heart muscle resulting in inadequate delivery of oxygen to meet the heart muscle's metabolic needs. People with hypertensive crises often have chest pain as a result of this mismatch and may suffer from left ventricular dysfunction. The kidneys will be affected, resulting in blood and/or protein in the urine, and acute kidney failure. It differs from other complications of hypertension in that it is accompanied by swelling of the optic disc.[2] This can be associated with hypertensive retinopathy.

Other signs and symptoms can include:

- Chest pain

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- Headache

- Nosebleeds that are difficult to stop

- Dyspnea

- Fainting or the sensation of the world spinning around them

- Severe anxiety

- Agitation

- Altered mental status

- Abnormal sensations

Chest pain requires immediate lowering of blood pressure (such as with sodium nitroprusside infusions), while urgencies can be treated with oral agents, with the goal of lowering the mean arterial pressure (MAP) by 20% in 1–2 days with further reduction to "normal" levels in weeks or months. The former use of oral nifedipine, a calcium channel blocker, has been strongly discouraged as it has led to excessive falls in blood pressure with serious and fatal consequences.[3]

Sometimes, the term hypertensive emergency is also used as a generic term, comprising both hypertensive emergency, as a specific term for a serious and urgent condition of elevated blood pressure, and hypertensive urgency, as a specific term of a less serious and less urgent condition (the terminology hypertensive crisis is usually used in this sense). Hypertensive crises must be carefully distinguished to avoid risks as they differ in managements. While intravenous medications are recommended to treat hypertensive emergency, they are not indicated for hypertensive urgency as aggressive lowering of blood pressure carries risk.[4]

Definition

| Terminology[5] | Systolic pressure | Diastolic pressure |

| Hypertensive crisis - emergency | ≥ 180 mm Hg | ≥ 120 mm Hg |

The term hypertensive emergency is primarily used as a specific term for a hypertensive crisis with a diastolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 120 mmHg or systolic blood pressure greater than or equal to 180 mmHg.[5] Hypertensive emergency differs from hypertensive crisis in that, in the former, there is evidence of acute organ damage.[5]

Causes

Many factors and causes are contributory in hypertensive crises. One main cause is the discontinuation of antihypertensive medications. Other common causes of hypertensive crises are autonomic hyperactivity, collagen-vascular diseases, drug use (particularly stimulants, especially cocaine and amphetamines and their substituted analogues), glomerulonephritis, head trauma, neoplasias, preeclampsia and eclampsia, and renovascular hypertension.[6]

Consequences

During a hypertensive emergency uncontrolled blood pressure leads to progressive or impending end-organ dysfunction. Therefore, it is important to lower the blood pressure aggressively. Acute end-organ damage may occur, affecting the neurological, cardiovascular, renal, or other organ systems. Some examples of neurological damage include hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral vascular accident/cerebral infarction, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and intracranial bleeding. Cardiovascular system damage can include myocardial ischemia/infarction, acute left ventricular dysfunction, acute pulmonary edema, and aortic dissection. Other end-organ damage can include acute kidney failure or insufficiency, retinopathy, eclampsia, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia.

Extreme blood pressure can lead to problems in the eye, such as retinopathy or damage to the blood vessels in the eye.[7]

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of hypertensive emergency is not well understood.[8] Failure of normal autoregulation and an abrupt rise in systemic vascular resistance are typical initial components of the disease process.[9]

Hypertensive emergency pathophysiology includes:

- Abrupt increase in systemic vascular resistance, likely related to humoral vasoconstrictors

- Endothelial injury

- Fibrinoid necrosis of the arterioles

- Deposition of platelets and fibrin

- Breakdown of normal autoregulatory function

The resulting ischemia prompts further release of vasoactive substances, completing a vicious cycle. If the process is not stopped, a vicious cycle of homeostatic failure begins, leading to loss of cerebral and local autoregulation, organ system ischemia and dysfunction, and myocardial infarction.[10]

It is estimated that single-organ involvement is found in approximately 83% of hypertensive emergency patients, two-organ involvement in about 14% of patients, and multi-organ failure (failure of at least 3 organ systems) in about 3% of patients.

The most common clinical presentations of hypertensive emergencies are cerebral infarction (24.5%), pulmonary edema (22.5%), hypertensive encephalopathy (16.3%), and congestive heart failure (12%). Less common presentations include intracranial bleeding, aortic dissection, and eclampsia.[9]

Cerebral autoregulation is the ability of the blood vessels in the brain to maintain a constant blood flow. It has been shown that people who suffer from chronic hypertension can tolerate higher arterial pressure before their autoregulation system is disrupted. Hypertensives also have an increased cerebrovascular resistance which puts them at greater risk of developing cerebral ischemia if the blood flow decreases into a normotensive range. On the other hand, sudden or rapid rises in blood pressure may cause hyperperfusion and increased cerebral blood flow, causing increased intracranial pressure and cerebral edema. Hypertensive encephalopathy - characterized by hypertension, altered mentation, and swelling of the optic disc- is one of the clinical manifestations of cerebral edema and tiny bleeds seen with dysfunction of cerebral autoregulation.[9]

Increased arterial stiffness, increased systolic blood pressure, and widened pulse pressures, all resulting from chronic hypertension, can lead to heart damage. Coronary perfusion pressures are decreased by these factors, which also increase myocardial oxygen consumption, possibly leading to left ventricular hypertrophy. As the left ventricle becomes unable to compensate for an acute rise in systemic vascular resistance, left ventricular failure and pulmonary edema or myocardial ischemia may occur.

Chronic hypertension has a great impact on the renal vasculature, leading to pathologic changes in the small arteries of the kidney. Affected arteries develop endothelial dysfunction and impairment of normal vasodilation, which alter renal autoregulation. When the renal autoregulatory system is disrupted, the intraglomerular pressure starts to vary directly with the systemic arterial pressure, thus offering no protection to the kidney during blood pressure fluctuations. During a hypertensive crisis, this can lead to acute renal ischemia.

Endothelial injury can occur as a consequence of severe elevations in blood pressure, with fibrinoid necrosis of the arterioles following. The vascular injury leads to deposition of platelets and fibrin, and a breakdown of the normal autoregulatory function. Ischemia occurs as a result, prompting further release of vasoactive substances. This process completes the vicious cycle.[6]

Treatment

Several classes of antihypertensive agents are recommended, with the choice depending on the cause of the hypertensive crisis, the severity of the elevation in blood pressure, and the usual blood pressure of the person before the hypertensive crisis. In most cases, the administration of intravenous sodium nitroprusside injection which has an almost immediate antihypertensive effect, is suitable (but in many cases not readily available). Other intravenous agents like nitroglycerine, nicardipine, labetalol, fenoldopam or phentolamine can also be used, but all have a delayed onset of action (by several minutes) compared to sodium nitroprusside.[11][12]

In addition, non-pharmacological treatment could be considered in cases of resistant malignant hypertension due to end stage kidney failure, such as surgical nephrectomy, laparoscopic nephrectomy, and renal artery embolization in cases of anesthesia risk.[13]

It is also important that the blood pressure is lowered smoothly, not too abruptly. The initial goal in hypertensive emergencies is to reduce the pressure by no more than 25% (within minutes to 1 or 2 hours), and then toward a level of 160/100 mm Hg within a total of 2–6 hours. Excessive reduction in blood pressure can precipitate coronary, cerebral, or renal ischemia and, possibly, infarction.[14]

The diagnosis of a hypertensive emergency is not based solely on an absolute level of blood pressure, but also on the typical blood pressure level of the patient before the hypertensive crisis occurs. Individuals with a history of chronic hypertension may not tolerate a "normal" blood pressure.

Epidemiology

Although an estimated 50 million or more adult Americans suffer from hypertension, the relative incidence of hypertensive crisis is relatively low (less than 1% annually). Nevertheless, this condition does affect upward of 500,000 Americans each year, and is therefore a significant cause of serious morbidity in the US.[15] About 14% of adults seen in hospital emergency departments in United States have a systolic blood pressure ≥180 mmHg.[16]

As a result of the use of antihypertensives, the rates of hypertensive emergencies has declined from 7% to 1% of people with high blood pressure. The 1–year survival rate has also increased. Before 1950, this survival rate was 20%, but it is now more than 90% with proper medical treatment.[9]

Estimates indicate that approximately 1% to 2% of people with hypertension develop hypertensive crisis at some point in their lifetime. Men are more commonly affected by hypertensive crises than women.

The rates of hypertensive crises has increased and hospital admissions tripled between 1983 and 1990, from 23,000 to 73,000 per year in the United States. The incidence of postoperative hypertensive crisis varies and such variation depends on the population examined. Most studies report and incidence of between 4% to 35%.[17]

Prognosis

Severe hypertension is a serious and potentially life-threatening medical condition. It is estimated that people who do not receive appropriate treatment only live an average of about three years after the event.[18]

The morbidity and mortality of hypertensive emergencies depend on the extent of end-organ dysfunction at the time of presentation and the degree to which blood pressure is controlled afterward. With good blood pressure control and medication compliance, the 10-year survival rate of patients with hypertensive crises approaches 70%.[19]

The risks of developing a life-threatening disease affecting the heart or brain increase as the blood flow increases. Commonly, ischemic heart attack and stroke are the causes that lead to death in patients with severe hypertension. It is estimated that for every 20 mm Hg systolic or 10 mm Hg diastolic increase in blood pressures above 115/75 mm Hg, the mortality rate for both ischemic heart disease and stroke doubles.

Several studies have concluded that African Americans have a greater incidence of hypertension and a greater morbidity and mortality from hypertensive disease than non-Hispanic whites.[20] It appears that hypertensive crisis is also more common in African Americans compared with other races.

Although severe hypertension is more common in the elderly, it may occur in children (though very rarely). Also, women have slightly increased risks of developing hypertension crises than do men. The lifetime risk for developing hypertension is 86-90% in females and 81-83% in males.

See also

References

- ↑ Thomas L (October 2011). "Managing hypertensive emergencies in the ED". Can Fam Physician. 57 (10): 1137–97. PMC 3192077. PMID 21998228.

- ↑ "malignant hypertension" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ↑ Rodriguez, Maria Alexandra; Kumar, Siva K.; De Caro, Matthew (March 2010). "Hypertensive crisis". Cardiology in Review. 18 (2): 102–107. doi:10.1097/CRD.0b013e3181c307b7. ISSN 1538-4683. PMID 20160537.

- ↑ Yang, Jeong Yun; Chiu, Sophia; Krouss, Mona (2018-02-26). "Overtreatment of Asymptomatic Hypertension—Urgency Is Not an Emergency: A Teachable Moment". JAMA Internal Medicine. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.0126.

- 1 2 3 Whelton, Paul K.; Carey, Robert M.; Aronow, Wilbert S.; Casey, Donald E.; Collins, Karen J.; Dennison Himmelfarb, Cheryl; DePalma, Sondra M.; Gidding, Samuel; Jamerson, Kenneth A.; Jones, Daniel W.; MacLaughlin, Eric J.; Muntner, Paul; Ovbiagele, Bruce; Smith, Sidney C.; Spencer, Crystal C.; Stafford, Randall S.; Taler, Sandra J.; Thomas, Randal J.; Williams, Kim A.; Williamson, Jeff D.; Wright, Jackson T. (13 November 2017). "2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults". Hypertension: HYP.0000000000000065. doi:10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065.

- 1 2 "Hypertensive Crises: Recognition and Management". Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ "Blurred Vision Causes". Archived from the original on 2011-01-28. Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ "Hypertensive Emergencies". Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- 1 2 3 4 "Pathophysiology". Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ "Vascular Biology Working Group". Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ Elliot, William J; Varon, Joseph; Bakris, George L. "Drugs used for the treatment of hypertensive emergencies". UpToDate. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ↑ Pak, Kirk J; Hu, Tian; Fee, Colin (2014). "Acute Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Appraisal of Guidelines". The Oschner Journal. 14 (4): 655–663. PMC 4295743. PMID 25598731.

A summary of recommendations from the selected guidelines is presented in Table 2.

- ↑ http://www.avicennajmed.com/article.asp?issn=2231-0770;year=2013;volume=3;issue=1;spage=23;epage=25;aulast=Alhamid;type=0

- ↑ Brewster LM, MD; Michael Sutters, MD (2006). "Hypertensive Urgencies & Emergencies - Hypertension Drug Therapy". Systemic Hypertension. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Vidt DG (2001). "Emergency room management of hypertensive urgencies and emergencies". Cleveland Clinic Foundation. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Shorr, Andrew F.; Zilberberg, Marya D.; Sun, Xiaowu; Johannes, Richard S.; Gupta, Vikas; Tabak, Ying P. (March 2012). "Severe acute hypertension among inpatients admitted from the emergency department". Journal of Hospital Medicine. 7 (3): 203–210. doi:10.1002/jhm.969. ISSN 1553-5606. PMID 22038891.

- ↑ "Hypertensive Crises" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-07-27.

- ↑ "Severe Hypertension Symptoms". Archived from the original on 2010-04-15. Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ "Mortality/Morbidity". Retrieved 2010-04-20.

- ↑ Howard, J. (1965). "Race Differences in Hypertension Mortality Trends: Differential Drug Exposure as a Theory". Systemic Hypertension. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 43: 202–218. JSTOR 3349030.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |