Shinkolobwe

Shinkolobwe mine, 1925 | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

Shinkolobwe mine | |

| Location | Shinkolobwe |

| Province | Katanga |

| Country | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Coordinates | 11°03′17.9″S 26°32′50.2″E / 11.054972°S 26.547278°ECoordinates: 11°03′17.9″S 26°32′50.2″E / 11.054972°S 26.547278°E |

| Production | |

| Products | Uranium ore |

| History | |

| Closed | 2004 |

Shinkolobwe, or Kasolo, or Chinkolobew, or Shainkolobwe, is a radium and uranium mine in the Katanga province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), located 20 km west of Likasi, 20 km south of Kambove, and about 145 km northwest of Lubumbashi.[1][2]

The mine produced uranium ore for the Manhattan Project. It was officially closed in 2004.

History

Shinkolobwe is the name of a nearby village, long since gone, and the name of an indigenous thorny fruit. According to Zoellner, it is also slang for "a man who is easygoing on the surface but who becomes angry when provoked".[3]

The mineral deposit was discovered in 1915 by an English geologist Robert Rich Sharp (1881–1958).[4][5] The mine was worked from 1921 onwards. Uranium-bearing ore was initially exported to Olen, Belgium for the extraction of radium,[6] and uranium. Only the richest ore was sent to Olen, with the remainder held in reserve. Open-cut mining was suspended at level 57 m and at the level 79 m underground in 1936, though exploration had commenced at level 114 m, and water pumps installed at level 150 m.[2][7]

Both Britain and France expressed interest in the Belgium inventory of uranium ore in 1939. Nothing further happened though after the Nazis occupied Belgium in 1940, gaining control of the ore still "on the docks".[3]:45[1]:186–187

Open-cut operations restarted in 1944, and underground in 1945. This required pumping the mine dry since the water table was at about 45 m. The 255 m level was reached in 1955.[2][8]

About 25,000 tU was produced over the subsequent two decades [1940-1960] from this vein-hosted deposit, but production ceased on independence in 1960, when the shafts were sealed and guarded.[9]

Gécamines is a state-controlled corporation founded in 1966 and a successor to the Union Minière du Haut Katanga (UMHK). Through a series of negotiations from 1960 to 1971 Gécamines acquired sole ownership of the Shinkolobwe resources, among other mines. It was reported in November 1998 that " At the other end of the deal is the Swiss-based Marc Rich commodity company, which did much of the "financial engineering" and has first refusal on the bulk of copper and cobalt production from the Groupe Central mines at Kababankola, Kamoya, Shinkolobwe, Kakanda and Kambove..." 'The wages of war' 20th November 1998. Thus 80% of Gécamines Groupe Central, including Shinkolobwe, was purchased by Virgin Islands based Rigepointe on 5th November 1998.[10]

Absent evidence to the contrary, Ridgepointe retained ownership of Shinkolobwe until May 2009, when its BVI registration became inactive following the imposition of US sanction and Mossack Fonseca's earlier desision to cut ties. [11]

In 2009, Misabiko blew the whistle on the government again, this time for its involvement in an illegal uranium mining plan at the notorious Shinkolobwe uranium mine that had been officially closed in 2004. He found out that the French nuclear corporation, Areva, was in secret negotiations with the Congo government. The French government and its then president, Nicolas Sarkozy, along with then Areva head, Anne Lauvergeon, had traveled to Congo. There, on March 26, 2009, they had secured a lightning quick deal with the Congo government for Areva to reopen uranium mining operations as the site.[12] In 2010 the government of the DRC has signed a contract for the legal and industrial exploitation of the Katanga uranium resources with the French energy company Areva. The details of this contract remain secret, but reportedly Areva has bought the right to the unlimited export of the Congolese uranium reserves. This deal has caused concern, as in the past Areva has been heavily criticised for its practices in the uranium mining business in other developing states, especially in Niger.[13]

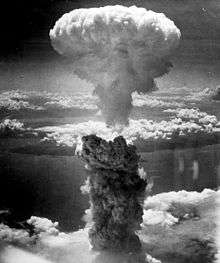

Uranium for the Manhattan Project

The United States used Shinkolobwe's uranium resources to supply the Manhattan Project to construct the atomic bomb in World War II. Edgar Sengier, then director of Union Minière du Haut Katanga, had stockpiled 1,200 tonnes of uranium ore in a warehouse on Staten Island, New York. This ore and an additional 3,000 tonnes of ore stored above-ground at the mine was purchased by Colonel Ken Nichols for use in the project. Nichols wrote:[14]

Our best source, the Shinkolobwe mine, represented a freak occurrence in nature. It contained a tremendously rich lode of uranium pitchblende. Nothing like it has ever again been found. The ore already in the United States contained 65 percent U3O8, while the pitchblende aboveground in the Congo amounted to a thousand tons of 65 percent ore, and the waste piles of ore contained two thousand tons of 20 percent U3O8. To illustrate the uniqueness of Sengier's stockpile, after the war the MED and the AEC considered ore containing three-tenths of 1 percent as a good find. Without Sengier’s foresight in stockpiling ore in the United States and aboveground in Africa, we simply would not have had the amounts of uranium needed to justify building the large separation plants and the plutonium reactors.

In 1940, 1200 tons of stockpiled uranium ore were shipped to the US by Edgar Sengier's African Metals Corp., a commercial arm of Union Miniere. Then, after the September 1942 agreement with Nichols, an average of 400 tons of Uranium oxide were shipped to the US each month. Initially, the port of Lobito was used to ship the ore, but later Matadi was used to improve security. Only two shipments were lost at sea. The aerodromes in Elizabethville and Leopoldville were also expanded. Additionally, the mine was reopened with the help of the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which involved draining the water and retooling the facility. Finally, the Office of Strategic Services were enlisted to deal with the threat of smuggling to Germany.[1]:3,6–7,11[3]:45–49

American interest in the Shinkolobwe mine for the purpose of developing of nuclear weapons led to the implementation of extensive security measures. Shinkolobwe's location was removed from maps and journalists were denied access to the mine and official information.

Postwar

Just as a lack of uranium ore impeded the German and Japanese attempts to make an atomic bomb, the Americans wanted to maintain their monopoly against the Soviets. According to Williams, "America had achieved a global hegemony, which was entirely reliant on its monopoly of Congolese uranium".[1]:231

Security measures were slightly more relaxed in the wake of World War II,[6] but in the 1950s, most journalists were able to gather only scraps of information on the mine's operation, from unofficial sources.[15][16] In 1950, a uranium processing plant was said to be under construction near the mine.[6] At the time, Shinkolobwe was believed to contain roughly half of the world's known reserves of uranium.[17]

In 1947, the U.S. received 1,440 tons of uranium concentrates from the Belgian Congo, 2,792 in 1951, and 1,600 in 1953. A processing plant was added nearby, and for increased security, a garrison was also established, with a supporting NATO military base in Kamina. Jadotville became a security checkpoint for foreigners. However, by the time of Congo independence, Union Miniere had sealed the mine with concrete.[1]:253–258

Closure

Artisanal mining has taken place on the site since 1997. The BBC's Premy Kibanga in Dar es Salaam says that already in 1998, uranium was seized in Tanzania and three people arrested. In 2002 Police in Tanzania seized 110kg of suspected uranium and arrested five people, including a national of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In early 2004 Arnaud Zejtman of the BBC found 6000 miners working the mine at Shinkolobwe. In July he reported that "Petwe Kapande, mayor of the nearby town of Likasi, told the BBC that nine bodies had been found. Some 30 miners were underground when the roof collapsed on Friday. "When I arrived, I found that six of the clandestine miners had been pulled out safe and sound, but others still remained trapped in the ruins," Mwema Teli, a safety official for the Congo government mines agency, told the Associated Press news agency."[18]

“They are digging as fast as they can dig, and everyone is buying it,” commented John Skinner, a mining engineer based in the nearby town of Likasi. “The problem is that nobody knows where it is going. There is no control at all.” [19]

US Cable 27 August 2004 - The current Governor of Katanga Province, Kisula Ngoy, has issued an order for all artisanal miners in and around Likasi and Lubumbashi to be moved to special artisanal zones, designated by the Minister of Mines, outside of Kolwezi, which is the furthest mining town from Lubumbashi. Econoff spoke with the leader of the Shinkolobwe artisanal miners union who confirmed that the Governor ordered the FARDC (army), ANR (intelligence service) and Mining Police to remove the miners from Shinkolobwe and all other sites in the Likasi/Lubumbashi area. He stated that all the miners - approximately 40,000 to 50,000 - are now in Likasi and Lubumbashi without money or means of employment. The miners also had to abandon the villages they built near the mine sites. (Comment. It is uncertain who is currently guarding and/or working the mines. End Comment.)[20]

The mine was officially closed on January 28, 2004, by presidential decree. However eight people died and a further thirteen people were injured in July 2004 when part of the old mine collapsed. Although industrial production has ceased with cement lids sealing off the mine shafts, there is evidence that some artisanal mining still goes on here. A United Nations inter-agency mission, led by the UN Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and organised through their Joint Environment Unit, visited the mine. The UNEP/OCHA concluded:

Shinkolobwe is representative of similar situations in Africa and elsewhere in the developing world. A strong link exists between rural poverty, environmental protection and this type of livelihood activity. Alternative income opportunities must be developed and integrated in parallel to artisanal exploitation if new livelihood options are to be found for these rural poor. A holistic, multidisciplinary approach within the context of poverty alleviation is essential to address this problem and avoid further human and environmental catastrophes.[21]

In October of 2005, a customs official in Tanzania made a routine inspection of a long-haul truck carrying several barrels of a metal called columbite-tantalite, otherwise known as coltan, a rare metal used in the manufacture of laptop computers and cell phones and other electronic goods. But he found a lode of unfamiliar black grit instead. One of his bosses later recalled the scene to a reporter: “There were several containers due to be shipped and they were all routinely scanned with a Geiger counter. This one was very radioactive. When we opened the container it was full of drums of coltan. Each drum contains about fifty kilograms of ore. When the first and second rows were removed, the ones after that were found to be drums of uranium.” A United Nations panel came in to investigate and concluded the source of both shipments had been illegal mining at Shinkolobwe.[22]

"Uranium for Iran" allegation

On July 18, 2006, the DRC Sanctions Committee (United Nations Security Council Committee Established Pursuant to Resolution 1533 (2004), to give it its full name) released a report dated June 15, 2006, which stated that artisanal mining for various minerals continues at the Shinkolobwe mine:

149. During an investigation into alleged smuggling of radioactive materials, the Group of Experts has learned that such incidents are far more frequent than assumed. According to Congolese experts on radioactive materials, organs of State security have, during the past six years, confiscated over 50 cases containing uranium or cesium in and around Kinshasa. The last significant incident occurred in March 2004 when two containers with over 100 kilograms of stable uranium-238 and uranium-235 were secured.

150. In response to a request for information by the Group of Experts the Government of the United Republic of Tanzania has provided limited data on four shipments that were seized over the past 10 years. Unfortunately the Government chose not to provide information about the quantities of the seized consignments nor the specific method of smuggling. At least in reference to the last shipment from October 2005, the Tanzanian Government left no doubt that the uranium was transported from Lubumbashi by road through Zambia to the United Republic of Tanzania. Attempts via Interpol to learn the precise origin within the Democratic Republic of the Congo have remained inconclusive.[23]

On August 9, 2006, the Sunday Times published a report claiming that Iran was seeking to import "bomb-making uranium" from the Shinkolobwe mine,[24] quoting the UN report of July 18, 2006. It gives "Tanzanian customs officials" as its sole source for the claim that the uranium was destined for processing in the former Soviet republic of Kazakhstan via the Iranian port of Bandar Abbas. Douglas Farah has compared this to the incorrect claim that Saddam Hussein was trying to buy yellowcake uranium from Niger, which formed part of the case made by George W. Bush for the invasion of Iraq.[25]

Geology

The formations of the Shinkolobwe ore deposit form a spur of the Mine Series wedged into a fold-fault. Uranium minerals, and associated cobalt, silver, nickel, bismuth and arsenic, occur as massive sulfide ore in veinlets along fractures, joints, and minor faults within the Katanga synclinorium. Uraninite mineralization occurred 630 Ma, when uraniferous solutions percolated into the dolomitic shales of the Precambrian Mine Series (Serie des Mines), under the Roche Argilotalqueuse (R.A.T.) nappe. The Mine Series is a Schist-Dolomite System postulated to be in the Roan System. This schistose-dolomite appears structurally between two contacts of the Kundelungu System, the Middle Kundelungu and the Lower Kundelungu, of the Katanga Group. The Lower and Upper Kundelungu form a double syncline, the northern limb of which overlies the Shinkolobwe Fault. These structural complexities aside, the Katanga stratigraphic column consists, top to bottom, of the Precambrian Kundelungu System (Upper, Middle and Lower), the Grand Congomerate and Mwashya Systems, the Schist-Dolomite System (Roan System-Mine Series of R.G.S., C.M.N., S.D., R.S.C., R.S.F., D. Strat., R.A.T. Gr., and R.A.T.) and the Kibara Group.[26][7]

Uraninite crystals from 1 to 4 centimeter cubes were common. New minerals identified here include ianthinite, becquerelite, schoepite, curite, fourmarierite, masuyite, vandendriesscheite, richetite, billietite, vandenbrandeite, kasolite, soddyite, sklodowskite, cuprosklodowskite, dewindtite, dumontite, renardite, parsonsite, saleite, sharpite, studtite, and diderichite. Similar uraninite deposits occur 36 km west at Swampo, and 120 km west at Kalongwe.[26][7]

Surface ores consist of oxidized minerals from supergene alteration above the water table and the formation of uranyl minerals. Below the water table, hypogene ores include uraninite (pitchblende), Co-Ni sulfides and selenides.[2]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams, Susan (2016). Spies in the Congo. New York: Public Affairs. pp. 2, 277. ISBN 9781610396547.

- 1 2 3 4 Heinrich, E. Wm. (1958). Mineralogy and Geology of Radioactive Raw Materials. New York: McGraw-Hill Book COmpany, Inc. pp. 289–297.

- 1 2 3 Zoellner, Tom (2009). Uranium. London: Penguin Books. p. 1. ISBN 9780143116721.

- ↑ (in French) Robert Rich Sharp, En prospection au Katanga il y a cinquante ans, Elisabethville, 1956.

- ↑ Hogarth, Donald, Robert Rich Sharp (1881–1958): prospector, engineer, and discoverer of the Shinkolobwe, Katanga, (Congo) radium-uranium ore-body, Society for the History of Discoveries

- 1 2 3 "Uranium ore, copper pacing Congo's output. American capital to have part soon in Katanga projects". The News-Herald. Franklin, Pennsylvania. 1950-05-18. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- 1 2 3 Derriks, J.J.; Vaes, J.F. (1956). The Shinkolobwe Uranium Deposit: Current Status of Our Geological and Metallogenic Knowledge, in Proceedings of the International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. New York: United Nations. pp. 94–128.

- ↑ Helmreich, Jonathan E. (1986). Gathering Rare Ores. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780691610399.

- ↑ Kinnaird, Judith A; Nex, Paul A.M (June 2016). "Uranium in Africa". Episodes. 39 (2): 335. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2016/v39i2/95782. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Wages of War" (vol39:23). Africa Confidential. Africa Confidential. 20 November 1998. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ "Alleged Mugabe cornies kept offshore firms years after UN alert raised". guardian.com. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Gunter, Linda Pentz. "Imprisoned, poisoned, tortured". Beyon Nuclear International. beyondnuclearinternational. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ "Uranium Mining in the DR Congo" (PDF). nuclear-risks.org. Ecumenical Network Central Africa. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Nichols, K. D. The Road to Trinity pages 44-47 (1987, Morrow, New York) ISBN 0-688-06910-X

- ↑ "Find world's richest uranium mines well guarded, output still a secret". Mansfield (Ohio) News-Journal. 1950-08-20. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ Cassidy, Morley (1953-08-02). "The word that is never said". The Kansas City Star. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ "Roughly half of the earth's uranium ore lies in the Belgian Congo". Daily Independent Journal. San Rafael, California. 1954-02-24. Retrieved 2015-01-16.

- ↑ Zajtman, Arnaud (12 July 2004). "DR Congo uranium mine collapses". BBC News Channel. BBC. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ Fleckner, Mads; Avery, John (July 2005). "Congo Uranium and the Tragedy of Hiroshima" (PDF). Pugwash Conference. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ↑ "REMOVAL OF ARTISANAL MINERS AROUND LIKASI - INCLUDING SHINKOLOBWE". wikileaks.org. Wikileaks. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ The DRC and Uranium for Iran accessed August 19, 2006

- ↑ Zoellner, Tom. "A (Radioactive) Cut in the Earth That Will Not Stay Closed". scientificamerican.com. Scientific American. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ DOCUMENTS RELATED TO THE SECURITY COUNCIL COMMITTEE ESTABLISHED PURSUANT TO RESOLUTION 1533 (2004) CONCERNING THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

- ↑ Iran's plot to mine uranium in Africa Sunday Times, August 9, 2006

- ↑ The DRC and Uranium for Iran. Retrieved August 19, 2006.

- 1 2 Byers, V.P. (1978). Principal Uranium Deposits of the World, USGS Open-File Report 78-1008. Washington: U.S. pp. 187–188.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shinkolobwe Mine. |