Demon core

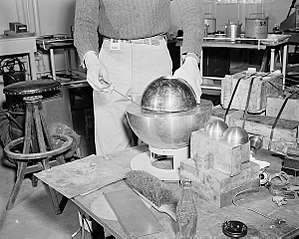

The demon core was a 6.2-kilogram (14 lb) subcritical mass of plutonium measuring 89 millimetres (3.5 in) in diameter, which was involved in two criticality accidents. The core was slated for use in a third World War II nuclear bomb, but remained in use for testing after Japan's surrender. It was designed with a small safety margin to ensure a successful explosion of the bomb. The device briefly went supercritical when it was accidentally placed in supercritical configurations during two separate experiments intended to guarantee the core was indeed close to the critical point. The incidents happened at the Los Alamos laboratory in 1945 and 1946, and resulted in the acute radiation poisoning and subsequent deaths of scientists Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin. After these incidents the spherical plutonium core was referred to as the "demon core".

Manufacturing and early history

The demon core (like the second core used in the bombing of Nagasaki) was a solid 6.2-kilogram (14 lb) sphere measuring 89 millimetres (3.5 in) in diameter. It consisted of three parts: two plutonium-gallium hemispheres and a ring, designed to keep neutron flux from "jetting" out of the joined surface between the hemispheres during implosion. The core of the device used in the Trinity nuclear test at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range in July did not have such a ring.[1][2]

The refined plutonium was shipped from the Hanford Site in Washington state to the Los Alamos Laboratory; an inventory document dated August 30 shows Los Alamos had expended "HS-1, 2, 3, 4; R-1" (the components of the Trinity and Nagasaki bombs) and had in its possession "HS-5, 6; R-2", finished and in the hands of quality control. Material for "HS-7, R-3" was in the Los Alamos metallurgy section, and would also be ready by September 5 (it is not certain whether this date allowed for the unmentioned "HS-8"'s fabrication to complete the fourth core).[3] The metallurgists used a plutonium-gallium alloy, which stabilized the δ phase allotrope of plutonium so it could be hot pressed into the desired spherical shape. As plutonium was found to corrode readily, the sphere was then coated with nickel.[4]

On August 10, Major General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., wrote to General of the Army George C. Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, to inform him that:

The next bomb of the implosion type had been scheduled to be ready for delivery on the target on the first good weather after August 24th, 1945. We have gained 4 days in manufacture and expect to ship the final components from New Mexico on August 12th or 13th. Providing there are no unforeseen difficulties in manufacture, in transportation to the theatre or after arrival in the theatre, the bomb should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after August 17th or 18th.[3]

Marshall added an annotation, "It is not to be released on Japan without express authority from the President", as President Harry S. Truman was waiting to see the effects of the first two attacks.[3] On August 13, the third bomb was scheduled. It was anticipated that it would be ready by August 16 to be dropped on August 19.[3] This was pre-empted by Japan's surrender on August 15, 1945, while preparations were still being made for it to be couriered to Kirtland Field. The third core remained at Los Alamos.[5]

First incident

The core, assembled, was designed to be at "−5 cents", or 5 percent below critical mass.[6] In this state there is only a small safety margin against extraneous factors that might increase criticality, causing the core to become supercritical, and then prompt critical, a brief state of rapid energy increase.[7] These factors are not common in the environment; they are circumstances like the compression of the solid metallic core – which would eventually be the method used to explode the bomb – the addition of more nuclear material, or provision of an external reflector which would reflect outbound neutrons back into the core. The experiments conducted at Los Alamos leading to the two fatal accidents were designed to guarantee that the core was indeed close to the critical point by arranging such reflectors and seeing how much neutron reflection was required to approach supercriticality.[6]

On August 21, 1945, the plutonium core produced a burst of neutron radiation that led to physicist Harry Daghlian's death. Daghlian made a mistake while performing neutron reflector experiments on the core. He was working alone; a security guard, Private Robert J. Hemmerly, was seated at a desk 10 to 12 feet (3 to 4 m) away.[8] The core was placed within a stack of neutron-reflective tungsten carbide bricks and the addition of each brick moved the assembly closer to criticality. While attempting to stack another brick around the assembly, Daghlian accidentally dropped it onto the core and thereby caused the core to go well into supercriticality, a self-sustaining critical chain reaction. He quickly moved the brick off the assembly, but received a fatal dose of radiation. He died 25 days later from acute radiation poisoning.[9]

| Name | Origin | Age at accident | Profession | Dose[8] | Aftermath | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haroutune "Harry" Krikor Daghlian, Jr. | New London, Connecticut | 24 | Physicist | 200 rad (2.0 Gy) neutron 110 rad (1.1 Gy) gamma | Died 25 days after the accident of acute radiation syndrome, haematopoietic focus | [10] |

| Private Robert J. Hemmerly | Whitehall, Ohio | 29 | Special Engineering Detachment (SED) guard | 8 rad (0.080 Gy) neutron 0.1 rad (0.0010 Gy) gamma | Died in 1978 (33 years after accident) of acute myelogenous leukemia at the age of 62 | [10] |

Second incident

On May 21, 1946,[11] physicist Louis Slotin and seven other Los Alamos personnel were in a Los Alamos laboratory conducting another experiment to verify the exact point at which a subcritical mass (core) of fissile material could be made critical by the positioning of neutron reflectors. Slotin, who was leaving Los Alamos, was showing the technique to Alvin C. Graves, who would use it in a final test before the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests scheduled a month later at Bikini Atoll. It required the operator to place two half-spheres of beryllium (a neutron reflector) around the core to be tested and manually lower the top reflector over the core via a thumb hole on the top. As the reflectors were manually moved closer and farther away from each other, scintillation counters measured the relative activity from the core. The half-spheres needed to maintain a slight separation between them in order to allow sufficient neutrons to escape, and the standard protocol was to use shims between them, as allowing them to close completely could result in the instantaneous formation of a critical mass and a lethal power excursion. Under Slotin's own, and unapproved, protocol, the shims were not used and the only thing preventing this was the blade of a standard straight screwdriver, manipulated by the scientist's other hand. Slotin, who was given to bravado, became the local expert, performing the test on almost a dozen occasions, often in his trademark blue jeans and cowboy boots, in front of a roomful of observers. Enrico Fermi reportedly told Slotin and others they would be "dead within a year" if they continued performing it.[12] Scientists referred to this flirting with the possibility of a nuclear chain reaction as "tickling the dragon's tail", based on a remark by physicist Richard Feynman, who compared the experiments to "tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon".[13][14]

On the day of the accident, Slotin's screwdriver slipped outward a fraction of an inch while he was lowering the top reflector, allowing the reflector to fall into place around the core. Instantly there was a flash of blue light and a wave of heat across Slotin's skin; the core had become supercritical, releasing an intense burst of neutron radiation estimated to have lasted about a half second.[6] Slotin quickly twisted his wrist, flipping the top shell to the floor. The heating of the core and shells stopped the criticality within seconds of its initiation,[15] while Slotin's reaction prevented a recurrence and ended the accident. The position of Slotin's body over the apparatus also shielded the others from much of the neutron radiation, but he received a lethal dose of 1,000 rad (10 Gy) neutron and 114 rad (1.14 Gy) gamma radiation in under a second and died nine days later from acute radiation poisoning. The nearest person to Slotin, Graves, who was watching over Slotin's shoulder and was thus partially shielded by him, received a high but non-lethal radiation dose. Graves was hospitalized for several weeks with severe radiation poisoning and developed chronic neurological and vision problems as a result of the exposure.[8] He died 20 years later, at age 55, of a heart attack. It may have been caused by hidden complications from radiation exposure, but could also have been genetic in nature, as his father had died from the same cause.[16][17][18]

The second accident was reported by the Associated Press on 26 May 1946: "Four men injured through accidental exposure to radiation in the government's atomic laboratory here [Los Alamos] have been discharged from the hospital and 'immediate condition' of four others is satisfactory, the Army reported today. Dr. Norris E. Bradbury, project director, said the men were injured last Tuesday in what he described as an experiment with fissionable material."[19]

Results of subsequent studies

There have been five studies performed regarding the amount of radiation each person involved received in the accident; these are the latest, dated 1978, from a table in this reference:

| Name | Origin | Age at accident | Profession | Dose[8] | Aftermath | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Louis Alexander Slotin | Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada | 35 | physicist | 1,000 rad (10 Gy) neutron 114 rad (1.14 Gy) gamma | died 9 days after the accident of acute radiation syndrome, gastrointestinal focus | [11] |

| Alvin C. Graves | Austin, Texas | 34 | physicist | 166 rad (1.66 Gy) neutron 26 rad (0.26 Gy) gamma | died in 1965 (19 years after the accident) of myocardial infarction, with aggravating "compensated myxedema and cataracts", while skiing | [8] |

| Samuel Allan Kline | Chicago, Illinois | physics student, later patent attorney | died in 2001 (55 years after the accident); refused to take part in studies | [8] | ||

| Marion Edward Cieslicki | Mt. Lebanon, Pennsylvania | 23 | physicist | 12 rad (0.12 Gy) neutron 4 rad (0.040 Gy) gamma | died of acute myelocytic leukemia in 1965 (19 years after the accident) | [8] |

| Dwight Smith Young | Chicago, Illinois | 54 | photographer | 51 rad (0.51 Gy) neutron 11 rad (0.11 Gy) gamma | died of aplastic anemia and bacterial endocarditis in 1975 (29 years after the accident) | [8] |

| Raemer Edgar Schreiber | McMinnville, Oregon | 36 | physicist | 9 rad (0.090 Gy) neutron 3 rad (0.030 Gy) gamma | died of natural causes in 1998 (52 years after the accident), at the age of 88 | [8][15] |

| Theodore Perlman | Louisiana | 23 | engineer | 7 rad (0.070 Gy) neutron 2 rad (0.020 Gy) gamma | "alive and in good health and spirits" as of 1978; probably died in June 1988 (42 years after the accident), in Livermore, California[20] | [8] |

| Private Patrick Joseph Cleary | New York City | 21 | security guard | 33 rad (0.33 Gy) neutron 9 rad (0.090 Gy) gamma | Sergeant 1st Class Cleary was KIA on 3 Sep 1950 while fighting with the 8th Cavalry Regiment, US Army in the Korean War.[21] | [8] |

Two machinists, Paul Long and another, unidentified, in another part of the building, 20 to 25 feet away, were not treated.[22]

After these incidents the core, originally known as "Rufus", was referred to as the "demon core".[3][23] Hands-on criticality experiments were stopped, and remote-control machines and TV cameras were designed by Schreiber, one of the survivors, to perform such experiments with all personnel at a quarter-mile distance.[15]

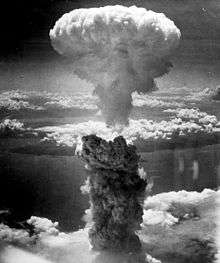

Operation Crossroads

The demon core was intended to be used in the Operation Crossroads nuclear tests, but after the criticality accident, time was needed for its radioactivity to decline and for it to be re-evaluated for the effects of the fission products it held, some of which could be very poisonous to the desired level of fission. The next two cores were shipped for use in Able and Baker, and the demon core was scheduled to be shipped later for the third test of the series, provisionally named Charlie, but that test was cancelled due to the unexpected level of radioactivity resulting from the underwater Baker test and the inability to decontaminate the target warships. The core was later melted down and the material recycled for use in other cores.[23][24]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Demon core. |

- ↑ Wellerstein, Alex. "You don't know Fat Man". Restricted data blog. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ↑ Coster-Mullen, John (2010). Core Differences, from "Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man". Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014. An error: the illustration caption states the Fat Man core was plated in silver; it was plated in nickel, as the silver plating on the gadget core blistered. The disk in the drawings is a gold foil gasket.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wellerstein, Alex. "The Third Core's Revenge". Restricted data blog. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- ↑ Baker, Richard D.; Hecker, Siegfried S.; Harbur, Delbert R. (1983). Plutonium: A Wartime Nightmare but a Metallurgist's Dream (PDF). Los Alamos Science. Los Alamos National Laboratory. pp. 142–151. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 22 November 2010.

- ↑ Shreiber, Raemer; Rhodes, Richard (1993). "Raemer Schreiber's Interview". Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved May 28, 2015. Raemer Schreiber being interviewed by Richard Rhodes

- 1 2 3 McLaughlin, Thomas P.; Monahan, Shean P.; Pruvost, Norman L.; Frolov, Vladimir V.; Ryazanov, Boris G.; Sviridov, Victor I. (May 2000). "A review of criticality incidents, 2000 Revision (LA-13638)" (PDF): 70–78. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ↑ Stater, Robert G. (December 13, 2012). "Prompt Criticality: A Concept with False Credentials". Nuke Facts. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hempelman, Louis Henry; Lushbaugh, Clarence C.; Voelz, George L. (October 19, 1979). What Has Happened to the Survivors of the Early Los Alamos Nuclear Accidents? (PDF). Conference for Radiation Accident Preparedness. Oak Ridge: Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. LA-UR-79-2802. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved January 5, 2013. Patient numbers in this document have been identified as: 1 - Daghlian, 2 - Hemmerly, 3 - Slotin, 4 - Graves, 5 - Kline, 6 - Young, 7 - Cleary, 8 - Cieleski, 9 - Schreiber, 10 - Perlman

- ↑ Miller, Richard L. (1991). Under the Cloud: The Decades of Nuclear Testing. The Woodlands, Texas: Two Sixty Press. pp. 68, 77. ISBN 0-02-921620-6.

- 1 2 Dion, Arnold. "Acute Radiation Sickness". Tripod. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- 1 2 "A Review of Criticality Accidents" (PDF). Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. September 26, 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ Welsome, Eileen (1999). The Plutonium Files (PDF). New York: Dial Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-385-31402-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ↑ Weber, Bruce (10 April 2001). "Theater Review; A Scientist's Tragic Hubris Attains Critical Mass Onstage". New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ↑ Shepherd-Barr, Kirsten; Lustig, Harry (November–December 2002). "Science as Theater: The Slip of the Screwdriver". American Scientist. Sigma Xi. 90 (6): 550–555. Bibcode:2002AmSci..90..550S. doi:10.1511/2002.6.550.

- 1 2 3 Calloway, Larry (July 1995). "Nuclear Naiveté" (PDF). Albuquerque Journal. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 16, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ↑ Clifford T. Honicker (November 19, 1989). "America's Radiation Victims: The Hidden Files". New York Times. p. 11. Archived from the original on August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Alsop, Stewart; Robert E. Lapp (March 6, 1954). "The Strange Death of Louis Slotin" (PDF). Saturday Evening Post. 226 (36). pp. 25ff. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2014. Retrieved April 3, 2014.

- ↑ Clifford T. Honicker (November 19, 1989). "America's Radiation Victims: The Hidden Files". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 17, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ Associated Press, "Several at Atomic Bomb Laboratory Injured", The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Monday 27 May 1946, Volume 52, page 1.

- ↑ State of California. California Death Index, 1940-1997. Sacramento, CA, USA: State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics.

- ↑ American Battle Monuments Commission. Korean War Listing.

- ↑ "Louis Slotin". Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- 1 2 Wellerstein, Alex (May 21, 2016). "The Demon Core and the Strange Death of Louis Slotin". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 24, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2016.

- ↑ Wellerstein, Alex (May 23, 2016). "The blue flash". Restricted Data. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2016.