Salmeterol

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Serevent |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Inhalation (MDI, DPI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 96% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 5.5 hours |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.122.879 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

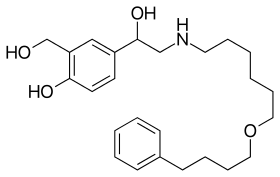

| Formula | C25H37NO4 |

| Molar mass | 415.57 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| | |

Salmeterol is a long-acting β2 adrenergic receptor agonist (LABA) used in the maintenance and prevention of asthma symptoms and maintenance of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) symptoms.[1] Symptoms of bronchospasm include shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing and chest tightness. It is also used to prevent breathing difficulties during exercise (exercise-induced bronchoconstriction).[2] It is marketed as Serevent in the US.[3] It is available as a dry powder inhaler that releases a powdered form of the drug. It was previously available as a metered-dose inhaler (MDI) but was discontinued in the US in 2002.[1][4] It is still available as an MDI in the UK as of 2013.

Medical uses

Salmeterol is used in moderate-to-severe persistent asthma following previous treatment with a short-acting β2 adrenoreceptor agonist (SABA) such as salbutamol (albuterol). LABAs should not be used as a monotherapy, instead, they should be used concurrently with an inhaled corticosteroid, such as beclometasone dipropionate or fluticasone propionate in the treatment of asthma to minimize serious reactions such as asthma-related deaths. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), LABAs may be used as monotherapy or in combination with corticosteroids. In exercise-induced bronchospasm monotherapy may be indicated in patients without persistent asthma. LABAs should not be used to treat acute symptoms.[1][5][6] The primary noticeable difference of salmeterol from salbutamol, and other short-acting β2 adrenoreceptor agonists (SABAs), is its duration of action. Salmeterol lasts approximately 12 hours in comparison with the salbutamol, which last about 4–6 hours.[1][5] When used regularly every day as prescribed, inhaled salmeterol decreases the number and severity of asthma attacks. However, like all LABA medications, it is not for use in relieving an asthma attack that has already started. Inhaled salmeterol works like other β2 agonists, causing bronchodilation by relaxing the smooth muscle in the airway so as to treat the exacerbation of asthma. The long duration of action occurs by the molecules initially diffusing into the plasma membrane of the lung cells, and then slowly being released back outside the cell where they can come into contact with the β2 adrenoreceptors, with the long carbon chain forming an anchor in the membrane. Salmeterol binding to the β2 adrenoreceptor does not induce desensitization or internalization of receptors which may also contribute to its long therapeutic duration of action. Formoterol has been demonstrated to have a faster onset of action than salmeterol as a result of a lower lipophilicity, and has also been demonstrated to be more potent—a 12 µg dose of formoterol has been demonstrated to be equivalent to a 50 µg dose of salmeterol.[2][7]

Pregnancy and lactation

The FDA assigns a Category C to salmeterol in pregnancy. Salmeterol use during pregnancy must be decided based on the risks versus benefits to the mother. There are no well-controlled studies with salmeterol in pregnant women. Some animal studies showed developmental malformation when the mother was given several clinical doses orally. In rats, salmeterol xinafoate is excreted in the milk. However, since there are no data to show excretion of salmeterol in a mother's breast milk, a decision on whether to continue or discontinue therapy should be decided based on the important benefits it provides to the mother. Pregnant and lactating women should consult their doctors before using salmeterol.[8]

Side effects

Due to its vasodilation properties, the common side effects of salmeterol are dizziness, sinus infection, and migraine headaches. In most cases, salmeterol side effects are minor and either don't require treatment or can easily be treated. Certain side effects, however, should be reported to a healthcare provider immediately. Some of these more serious side effects include a very fast heart rate, high blood pressure, and worsening breathing problems.[9]

Structure-activity relationship

Salmeterol has an aryl alkyl group with a chain length of 11 atoms from the amine. This bulkiness makes the compound more lipophilic and it also makes it selective to β2 adrenergic receptors.[10]

History

Salmeterol, first marketed and manufactured by Glaxo (now GlaxoSmithKline, GSK) in the 1980s, was released as Serevent in 1990.[4] The product is marketed by GSK under the Allen & Hanburys brand in the UK.

In November 2005, the US Food and Drug Administration released a health advisory, alerting the public to findings that show the use of long-acting β2 agonists could lead to a worsening of symptoms, and in some cases death.[11]

While the use of inhaled LABAs are still recommended in asthma guidelines for the resulting improved symptom control,[12] further concerns have been raised. A large meta-analysis of pooled results from 19 trials with 33,826 participants, suggests that salmeterol may increase the small risks of asthma-related deaths, and this additional risk is not reduced with the additional use of inhaled steroids (e.g., as with the combination product fluticasone/salmeterol).[13] This seems to occur because although LABAs relieve asthma symptoms, they also promote bronchial inflammation and sensitivity without warning.[14]

Long-acting β2 adrenoceptor agonists (LABAs)

Currently available long-acting β2 adrenergic receptor agonists include salmeterol (inhaled or sustained-release oral), formoterol, bambuterol and some others. Combinations of inhaled steroids and these long-acting bronchodilators are becoming more widespread; the most common combination currently in use is fluticasone/salmeterol (brand names Seretide (UK) and Advair (U.S.)).

See also

- Vilanterol — an ultra-long-acting β2 adrenoreceptor agonist with a similar chemical structure.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 "global initiative for chronic obstructive disease" (PDF). goldcopd.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- 1 2 "National Asthma Education and Prevention Program". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "Salmeterol inhalation index". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- 1 2 "FDA" (PDF). fda.gov.

- 1 2 "global initiative for astma" (PDF). ginasthma.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "Use of long-acting beta agonist in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". mhra.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ "Recommended Medication for Asthma" (PDF). www.partnershiphp.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-03.

- ↑ "Serevent Diskus" (PDF). accessdata.fda.gov. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "Medtv". HealthSavy. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ Medicinal Chemistry of Adrenergics and Cholinergics Archived 2010-11-04 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Advair Diskus, Advair HFA, Brovana, Foradil, Perforomist, Serevent Diskus, and Symbicort Information (Long Acting Beta Agonists)". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ↑ British Thoracic Society & Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). British Guideline on the Management of Asthma. Guideline No. 63. Edinburgh:SIGN; 2004. (HTML Archived 2006-06-18 at the Wayback Machine., Full PDF Archived 2006-07-24 at the Wayback Machine., Summary PDF Archived 2006-07-24 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ Salpeter S, Buckley N, Ormiston T, Salpeter E (2006). "Meta-analysis: effect of long-acting beta agonists on severe asthma exacerbations and asthma-related deaths". Ann Intern Med. 144 (12): 904–12. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-12-200606200-00126. PMID 16754916.

- ↑ Krishna Ramanujan (June 9, 2006). "Common asthma inhalers cause up to 80 percent of asthma-related deaths, Cornell and Stanford researchers assert". ChronicalOnline - Cornell University.