Sacubitril/valsartan

| |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| Sacubitril | Neprilysin inhibitor |

| Valsartan | Angiotensin II receptor antagonist |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Entresto, Azmarda, other |

| Synonyms | LCZ696 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | entresto |

| License data | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| KEGG | |

Sacubitril/valsartan, sold under the brand name Entresto among others, is a combination drug for use in heart failure developed by Novartis. It consists of the neprilysin inhibitor sacubitril and the angiotensin receptor blocker valsartan, in a 1:1 mixture by molecule count. It is recommended for use as a replacement for an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker in people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.[1]

Potential side effects include angioedema, kidney problems, and low blood pressure.[1] The risk of kidney problems and increased levels of serum potassium with sacubitril/valsartan is lower than that of an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. The combination is sometimes described as an "angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor" (ARNi).

It was approved under the FDA's priority review process on July 7, 2015.[2] It is also approved in Europe.[3] In the USA, the wholesale cost for a year of sacubitril/valsartan is $4,560 per person as of 2015.[4] Similar class generic drugs without sacubitril, such as valsartan alone, cost approximately $48 a year.[5] One industry-funded analysis found a cost of $45,017 per QALY.[6] The wholesale cost to the National Health Service in the UK is approximately £1,200 per person per year.[7]

Medical uses

Sacubitril/valsartan can be used instead of an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin receptor blocker in people with heart failure and a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), alongside other standard therapies (e.g. beta-blockers) for heart failure.[1][2][8] It is not known whether sacubitril/valsartan is useful for the treatment of heart failure in people with normal LVEF.[8] The level of evidence to support its use is less than that for ACE inhibitors and ARBs.[1] In those with class 2 or 3 failure who do well with an ACE inhibitor or ARB but still have symptoms, changing to sacubitril/valsartan decreases the risk of death.[1] It has not been compared directly to ARBs as of 2016.[1]

Changing 100 people from an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin II receptor antagonist to sacubitril/valsartan for 2.3 years would prevent 3 deaths, 5 hospitalizations for heart failure, and 11 hospitalizations overall.[8]

Adverse effects

Common adverse effects in the main study were cough, hyperkalemia (high potassium levels in the blood, which can be caused by valsartan), kidney dysfunction, and hypotension (low blood pressure, a common side effect of vasodilators and ECF volume reducers). 12% of the patients withdrew from the study during the run-in phase because of such events.[8]

Sacubitril/valsartan is contraindicated in pregnancy because it contains valsartan, a known risk for birth defects.[9]

Pharmacology

Valsartan blocks the angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1). This receptor is found on both vascular smooth muscle cells, and on the zona glomerulosa cells of the adrenal gland which are responsible for aldosterone secretion. In the absence of AT1 blockade, angiotensin causes both direct vasoconstriction and adrenal aldosterone secretion, the aldosterone then acting on the distal tubular cells of the kidney to promote sodium reabsorption which expands extracellular fluid (ECF) volume. Blockade of (AT1) thus causes blood vessel dilation and reduction of ECF volume.[10][11]

Sacubitril is a prodrug that is activated to sacubitrilat (LBQ657) by de-ethylation via esterases.[12] Sacubitrilat inhibits the enzyme neprilysin,[13] a neutral endopeptidase that degrades vasoactive peptides, including natriuretic peptides, bradykinin, and adrenomedullin. Thus, sacubitril increases the levels of these peptides, causing blood vessel dilation and reduction of ECF volume via sodium excretion.[14]

Neprilysin also has a role in clearing the protein amyloid beta from the cerebrospinal fluid, and its inhibition by sacubitril has shown increased levels of AB1-38 in healthy subjects (Entresto 194/206 for two weeks). Amyloid beta is considered to contribute to the development of Alzheimer's disease.[9]

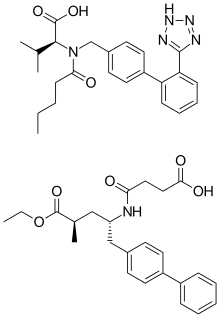

Chemistry

Sacubitril/valsartan is co-crystallized sacubitril and valsartan, in a one-to-one molar ratio. One sacubitril/valsartan complex consists of six sacubitril anions, six valsartan anions, 18 sodium cations, and 15 molecules of water, resulting in the molecular formula C288H330N36Na18O48·15H2O and a molecular mass of 5748.03 g/mol.[15][16]

The substance is a white powder consisting of thin hexagonal plates. It is stable in solid form as well as in aqueous (watery) solution with a pH of 5 to 7, and has a melting point of about 138 °C (280 °F).[16]

History

During its development by Novartis, Entresto was known as LCZ696. It was approved under the FDA's priority review process on July 7, 2015.[2] It was also approved in Europe in 2015.[3]

Society and culture

Trial design

There was controversy over the PARADIGM-HF trial—the Phase III trial on the basis of which the drug was approved by the FDA. For example, both Richard Lehman, a physician who writes a weekly review of key medical articles for the BMJ Blog and a December 2015 report from the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER) found that the risk–benefit ratio was not adequately determined because the design of the clinical trial was too artificial and did not reflect people with heart failure that doctors usually encounter.[4]:28[17] On the other hand, in December 2015 Steven Nissen and other thought leaders in cardiology said that the approval of sacubitril/valsartan had the greatest impact on clinical practice in cardiology in 2015, and Nissen called the drug "a truly a breakthrough approach."[18]

One 2015 review stated that sacubitril/valsartan represents "an advancement in the chronic treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction" but that widespread clinical success with the drug will require taking care to use it in appropriate patients, specifically those with characteristics similar to those in the clinical trial population.[19] Another 2015 review called the reductions in mortality and hospitalization conferred by sacubitril/valsartan "striking", but noted that its effects in heart failure people with hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, and the elderly needed to be evaluated further.[20]

Cost

The wholesale cost for a year of sacubitril/valsartan in the USA is $4,560 per person as of 2015,[4] but the cost to the NHS in the UK is less than £1,200 per person per year.[7] Similar class generic drugs without sacubitril, such as valsartan alone, cost approximately $48 a year.[5] One analysis found a cost of $45,017 per QALY.[6]

Research

The PARADIGM-HF trial (in which Milton Packer was one of the principal investigators) compared treatment with sacubitril/valsartan to treatment with enalapril.[21] People with heart failure and reduced LVEF (10,513) were sequentially treated on a short-term basis with enalapril and then with sacubitril/valsartan. Those that were able to tolerate both regimens (8442, 80%) were randomly assigned to long-term treatment with either enalapril or sacubitril/valsartan. Participants were mainly white (66%), male (78%), middle aged (median 63.8 +/- 11 years) with NYHA stage II (71.6%) or stage III (23.1%) heart failure.[22]

The trial was stopped early after a prespecified interim analysis revealed a reduction in the primary endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure in the sacubitril/valsartan group relative to those treated with enalapril. Taken individually, the reductions in cardiovascular death and heart failure hospitalizations retained statistical significance.[8] Relative to enalapril, sacubitril/valsartan provided reductions[22] in

- the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure (incidence 21.8% vs 26.5%)

- cardiovascular death (incidence 13.3% vs 16.5%)

- first hospitalization for worsening heart failure (incidence 12.8% vs 15.6%), and

- all-cause mortality (incidence 17.0% vs 19.8%)

The favorable effect of sacubitril/valsartan was seen in all subgroups examined, including those based on age, sex, weight, race, NYHA class, presence or absence of reduced kidney function, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and prior hospitalization.[9] Additional analyses of the trial demonstrated a meaningful representation of minority groups and well as a benefit in patients with an implantable cardiac device. Limitations of the trial include scarce experience with initiation of therapy in hospitalized patients and in those with NYHA heart failure class IV symptoms.[23][24]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yancy, CW; Jessup, M; Bozkurt, B; Butler, J; Casey DE, Jr; Colvin, MM; Drazner, MH; Filippatos, G; Fonarow, GC; Givertz, MM; Hollenberg, SM; Lindenfeld, J; Masoudi, FA; McBride, PE; Peterson, PN; Stevenson, LW; Westlake, C (20 May 2016). "2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America". Circulation. 134 (13): e282–e293. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435. PMID 27208050.

- 1 2 3 "FDA approves new drug to treat heart failure". Food and Drug Administration. 7 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Entresto". EMA. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- 1 2 3 Daniel A. Ollendorf, et al., "CardioMEMS™ HF System (St. Jude Medical, Inc.) and Sacubitril/Valsartan (Entresto™, Novartis AG) for Management of Congestive Heart Failure", Institute for Clinical and Economic Review, 1 December 2015.

- 1 2 Pollack, Andrew (August 30, 2014). "New Novartis Drug Effective in Treating Heart Failure". New York Times.

- 1 2 Gaziano, TA; Fonarow, GC; Claggett, B; Chan, WW; Deschaseaux-Voinet, C; Turner, SJ; Rouleau, JL; Zile, MR; McMurray, JJ; Solomon, SD (1 September 2016). "Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Sacubitril/Valsartan vs Enalapril in Patients With Heart Failure and Reduced Ejection Fraction". JAMA Cardiology. 1 (6): 666–72. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2016.1747. PMID 27438344.

- 1 2 "Entresto". MIMS. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McMurray, John J.V.; et al. (August 30, 2014). "Angiotensin–Neprilysin Inhibition versus Enalapril in Heart Failure". N Engl J Med. 371 (11): 993–1004. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1409077. PMID 25176015.

- 1 2 3 "Entresto prescribing information" (PDF). Novartis. July 2015.

- ↑ Mutschler, Ernst; Schäfer-Korting, Monika (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8 ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 579. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

- ↑ Zouein, Fouad A.; De Castro Brás, Lisandra E.; Da Costa, Danielle V.; Lindsey, Merry L.; Kurdi, Mazen; Booz, George W. (2013). "Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 62 (1): 13–21. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e31829a4e61. PMC 3724214. PMID 23714774.

- ↑ Solomon, SD. "HFpEF in the Future: New Diagnostic Techniques and Treatments in the Pipeline". Boston. p. 48. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ↑ Gu, J; Noe, A; Chandra, P; Al-Fayoumi, S; Ligueros-Saylan, M; Sarangapani, R; Maahs, S; Ksander, G; Rigel, D. F.; Jeng, A. Y.; Lin, T. H.; Zheng, W; Dole, W. P. (2010). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of LCZ696, a novel dual-acting angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor (ARNi)". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 50 (4): 401–14. doi:10.1177/0091270009343932. PMID 19934029.

- ↑ Schubert-Zsilavecz, M; Wurglics, M. "Neue Arzneimittel 2010/2011" (in German).

- ↑ Monge, M.; Lorthioir, A.; Bobrie, G.; Azizi, M. (2013). "New drug therapies interfering with the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system for resistant hypertension". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 14 (4): 285–9. doi:10.1177/1470320313513408. PMID 24222656.

- 1 2 Lili Feng, L; et al. (2012). "LCZ696: a dual-acting sodium supramolecular complex". Tetrahedron Letters. 53 (3): 275–276. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.11.029.

- ↑ Richard Lehman’s journal review—8 September 2014. NEJM 4 Sep 2014. Vol 371. The BMJ, 8 September 2014.

- ↑ Roger Sergel for Medpage Today. 5 Game-Changers in Cardiology in 2015: Entresto

- ↑ Lillyblad MP (2015). "Dual Angiotensin Receptor and Neprilysin Inhibition with Sacubitril/Valsartan in Chronic Systolic Heart Failure: Understanding the New PARADIGM". Ann Pharmacother. 49 (11): 1237–51. doi:10.1177/1060028015593093. PMID 26175499.

- ↑ Bavishi C, Messerli FH, Kadosh B, Ruilope LM, Kario K (2015). "Role of neprilysin inhibitor combinations in hypertension: insights from hypertension and heart failure trials". Eur. Heart J. 36 (30): 1967–73. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv142. PMID 25898846.

- ↑ Husten, Larry (March 31, 2014). "Novartis Trial Was Stopped Early Because Of A Significant Drop In Cardiovascular Mortality". Forbes.

- 1 2 King JB, Bress AP, Reese AD, Munger MA (2015). "Neprilysin Inhibition in Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Clinical Review". Pharmacotherapy. 35 (9): 823–37. doi:10.1002/phar.1629. PMID 26406774.

- ↑ Havakuk O, Elkayam U. Angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibition. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22:356-364. doi: 10.1177/1074248416683049.

- ↑ Perez AL, Kittipibul V, Tang WHW, Starling RC. Patients not meeting PARADIGM-HF enrollment criteria are eligible for sacubitril/valsartan on the basis of FDA Approval: the need to close the gap. JACC Heart Fail. 2017;5:460-463. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.03.007.