Mole (unit)

| Mole | |

|---|---|

| Unit system | SI base unit |

| Unit of | Amount of substance |

| Symbol | mol |

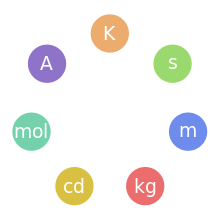

The mole is the unit of measurement for amount of substance in the International System of Units (SI). The unit is defined as the amount or sample of a chemical substance that contains as many constitutive particles, e.g., atoms, molecules, ions, electrons, or photons, as there are atoms in 12 grams of carbon-12 (12C), the isotope of carbon with standard atomic weight 12 by definition. This number is expressed by the Avogadro constant, which has a value of approximately 6.02214076×1023 mol−1. The mole is an SI base unit, with the unit symbol mol.

At its next meeting in November 2018 the CGPM is expected to accept the proposed redefinition of the mole, kilogram, ampere and kelvin, which will define the mole to have exactly 6.02214076×1023 elementary entities.[1]

The mole is widely used in chemistry as a convenient way to express amounts of reactants and products of chemical reactions. For example, the chemical equation 2 H2 + O2 → 2H2O implies that 2 mol dihydrogen (H2) and 1 mol dioxygen (O2) react to form 2 mol water (H2O). The mole may also be used to represent the number of atoms, ions, or other entities in a given sample of a substance. The concentration of a solution is commonly expressed by its molarity, defined as the amount of dissolved substance per unit volume of solution, for which the unit typically used is moles per litre (mol/l).

The term gram-molecule was formerly used for essentially the same concept.[2] The term gram-atom has been used for a related but distinct concept, namely a quantity of a substance that contains Avogadro's number of atoms, whether isolated or combined in molecules. Thus, for example, 1 mole of MgBr2 is 1 gram-molecule of MgBr2 but 3 gram-atoms of MgBr2.[3][4]

Definition and related concepts

Amount of substance is a measure of the quantity of substance proportional to the number of its entities. As of 2011, the mole is defined by International Bureau of Weights and Measures as:

- The mole is the amount of substance of a system which contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 0.012 kilogram of carbon 12.

- When the mole is used, the elementary entities must be specified and may be atoms, molecules, ions, electrons, other particles, or specified groups of such particles.

Thus, by definition, one mole of pure 12C has a mass of exactly 12 g.

The molar mass of a substance is the mass of a sample divided by the amount of substance in that sample. This is a constant for any given substance. Since the unified atomic mass unit (symbol: u, or Da) is defined as 1/12 of the mass of the 12C atom, it follows that the molar mass of a substance, measured in grams per mole, is numerically equal to its mean atomic or molecular mass expressed in Da.

One can determine the amount of a known substance, in moles, by dividing the sample's mass by the substance's molar mass.[5] Other methods include the use of the molar volume or the measurement of electric charge.[5]

The mass of one mole of a substance depends not only on its molecular formula, but also on the proportions within the sample of the isotopes of each chemical element present in it. For example, one mole of calcium-40 is 39.96259098±0.00000022 grams, whereas one mole of calcium-42 is 41.95861801±0.00000027 grams, and one mole of calcium with the normal isotopic mix is 40.078±0.004 grams.

Since the definition of the gram is not (as of 2011) mathematically tied to that of the atomic mass unit, the number of molecules per mole NA (the Avogadro constant) must be determined experimentally. The value adopted by CODATA in 2010 is NA = (6.02214129±0.00000027)×1023 mol−1.[6] In 2011 the measurement was refined to (6.02214078±0.00000018)×1023 mol−1.[7]

Mass and volume (properties of matter) are often used to quantify a sample of a substance. However, the volume changes with temperature and pressure. Similarly, due to relativistic effects, the mass of a sample changes with temperature, speed or gravity. This effect is very small at low temperature, speed or gravity, but at high speed like in a particle accelerator or theoretical space craft, the change is significant. The amount of substance remains the same regardless of temperature, pressure, speed or gravity, unless a (chemical or nuclear) reaction changes the number of particles.

History

The history of the mole is intertwined with that of molecular mass, atomic mass unit, Avogadro number and related concepts.

The first table of standard atomic weight (atomic mass) was published by John Dalton (1766–1844) in 1805, based on a system in which the relative atomic mass of hydrogen was defined as 1. These relative atomic masses were based on the stoichiometric proportions of chemical reaction and compounds, a fact that greatly aided their acceptance: It was not necessary for a chemist to subscribe to atomic theory (an unproven hypothesis at the time) to make practical use of the tables. This would lead to some confusion between atomic masses (promoted by proponents of atomic theory) and equivalent weights (promoted by its opponents and which sometimes differed from relative atomic masses by an integer factor), which would last throughout much of the nineteenth century.

Jöns Jacob Berzelius (1779–1848) was instrumental in the determination of relative atomic masses to ever-increasing accuracy. He was also the first chemist to use oxygen as the standard to which other masses were referred. Oxygen is a useful standard, as, unlike hydrogen, it forms compounds with most other elements, especially metals. However, he chose to fix the atomic mass of oxygen as 100, which did not catch on.

Charles Frédéric Gerhardt (1816–56), Henri Victor Regnault (1810–78) and Stanislao Cannizzaro (1826–1910) expanded on Berzelius' works, resolving many of the problems of unknown stoichiometry of compounds, and the use of atomic masses attracted a large consensus by the time of the Karlsruhe Congress (1860). The convention had reverted to defining the atomic mass of hydrogen as 1, although at the level of precision of measurements at that time—relative uncertainties of around 1%—this was numerically equivalent to the later standard of oxygen = 16. However the chemical convenience of having oxygen as the primary atomic mass standard became ever more evident with advances in analytical chemistry and the need for ever more accurate atomic mass determinations.

Developments in mass spectrometry led to the adoption of oxygen-16 as the standard substance, in lieu of natural oxygen. The old definition of the mole, based on carbon-12, was approved during the 1960s.[2][8] The four different definitions were equivalent to within 1%.

| Scale basis | Scale basis relative to 12C = 12 |

Relative deviation from the 12C = 12 scale |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic mass of hydrogen = 1 | 1.00794(7) | −0.788% |

| Atomic mass of oxygen = 16 | 15.9994(3) | +0.00375% |

| Relative atomic mass of 16O = 16 | 15.9949146221(15) | +0.0318% |

The name mole is an 1897 translation of the German unit Mol, coined by the chemist Wilhelm Ostwald in 1894 from the German word Molekül (molecule).[9][10][11] However, the related concept of equivalent mass had been in use at least a century earlier.[12]

The mole was made the seventh SI base unit in 1971 by the 14th CGPM.[13]

Criticism

Since its adoption into the International System of Units in 1971, numerous criticisms of the concept of the mole as a unit like the metre or the second have arisen:

- the number of molecules, etc. in a given amount of material is a fixed dimensionless quantity that can be expressed simply as a number, not requiring a distinct base unit;[8]

- the SI thermodynamic mole is irrelevant to analytical chemistry and could cause avoidable costs to advanced economies;[14]

- the mole is not a true metric (i.e. measuring) unit, rather it is a parametric unit and amount of substance is a parametric base quantity;[15]

- the SI defines numbers of entities as quantities of dimension one, and thus ignores the ontological distinction between entities and units of continuous quantities.[16]

In chemistry, it has been known since Proust's law of definite proportions (1794) that knowledge of the mass of each of the components in a chemical system is not sufficient to define the system. Amount of substance can be described as mass divided by Proust's "definite proportions", and contains information that is missing from the measurement of mass alone. As demonstrated by Dalton's law of partial pressures (1803), a measurement of mass is not even necessary to measure the amount of substance (although in practice it is usual). There are many physical relationships between amount of substance and other physical quantities, the most notable one being the ideal gas law (where the relationship was first demonstrated in 1857). The term "mole" was first used in a textbook describing these colligative properties.

Other units called "mole"

Chemical engineers use the concept extensively, but the unit is rather small for industrial use.[17] For convenience in avoiding conversions in the Imperial (or American customary units), some engineers adopted the pound-mole (notation lb-mol or lbmol), which is defined as the number of entities in 12 lb of 12C. One lb-mol is equal to 453.59237 mol;[18] which value is identical to the number of grams in an international avoirdupois pound.

In the metric system, chemical engineers once used the kilogram-mole (notation kg-mol), which is defined as the number of entities in 12 kg of 12C, and often referred to the mole as the gram-mole (notation g-mol), when dealing with laboratory data.[18]

Late 20th century chemical engineering practice came to use the kilomole (kmol), which is numerically identical to the kilogram-mole, but whose name and symbol adopt the SI convention for standard multiples of metric units – thus, kmol means 1000 mol. This is analogous to the use of kg instead of g. The use of kmol is not only for "magnitude convenience" but also makes the equations used for modelling chemical engineering systems coherent. For example, the conversion of a flowrate of kg/s to kmol/s only requires the molecular mass not the factor 1000 unless the basic SI unit of mol/s were to be used. Indeed, the appearance of any conversion factors in a model can cause confusion and is to be avoided; possibly a definition of coherence is the absence of conversion factors in sets of equations developed for modelling.

Concentrations expressed as kmol/m3 are numerically the same as those in mol/dm3 i.e. the molarity conventionally used by chemists for bench measurements; this equality can be convenient for scale-up.

Greenhouse and growth chamber lighting for plants is sometimes expressed in micromoles per square meter per second, where 1 mol photons = 6.02×1023 photons.[19]

Proposed redefinition

In 2011, the 24th meeting of the General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) agreed to a plan for a possible revision of the SI base unit definitions at an undetermined date.

The 26th meeting of the CGPM set for November 2018 has scheduled a formal vote on the proposed redefinition of SI base units mole, kilogram, ampere and kelvin. The mole will have exactly 6.02214076 x1023 specified "elementary entities".[20] The definition of the mole will no longer be based on mass. If the proposal is approved as expected, the new definitions will take effect 20 May 2019.

Related units

The SI units for molar concentration are mol/m3. However, most chemical literature traditionally uses mol/dm3, or mol dm−3, which is the same as mol/L. These traditional units are often denoted by a capital letter M (pronounced "molar"), sometimes preceded by an SI prefix, for example, millimoles per litre (mmol/L) or millimolar (mM), micromoles/litre (µmol/L) or micromolar (µM), or nanomoles/L (nmol/L) or nanomolar (nM).

The demal (D) is an obsolete unit for expressing the concentration of a solution. It is equal to molar concentration at 0 °C, i.e., 1 D represents 1 mol of the solute present in one cubic decimeter of the solution at 0 °C.[21] It was first proposed in 1924 as a unit of concentration based on the decimeter rather than the liter; at the time there was a factor of 1.000028 difference between the liter and the cubic decimeter.[22] The demal was used as a unit of concentration in electrolytic conductivity primary standards.[23] These standards were later redefined in terms of molar concentration.[24]

Mole Day

October 23, denoted 10/23 in the US, is recognized by some as Mole Day.[25] It is an informal holiday in honor of the unit among chemists. The date is derived from the Avogadro number, which is approximately 6.022×1023. It starts at 6:02 a.m. and ends at 6:02 p.m. Alternatively, some chemists celebrate June 2 or February 6, a reference to the 6.02 part of the constant.[26][27][28]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ IUPAC: "A new definition of the mole has arrived."

- 1 2 International Bureau of Weights and Measures (2006), The International System of Units (SI) (PDF) (8th ed.), pp. 114–15, ISBN 92-822-2213-6, archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-14

- ↑ Wang, Yuxing; Bouquet, Frédéric; Sheikin, Ilya; Toulemonde, Pierre; Revaz, Bernard; Eisterer, Michael; Weber, Harald W; Hinderer, Joerg; Junod, Alain; et al. (2003). "Specific heat of MgB2 after irradiation". Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter. 15 (6): 883–893. arXiv:cond-mat/0208169. Bibcode:2003JPCM...15..883W. doi:10.1088/0953-8984/15/6/315.

- ↑ Lortz, R.; Wang, Y.; Abe, S.; Meingast, C.; Paderno, Yu.; Filippov, V.; Junod, A.; et al. (2005). "Specific heat, magnetic susceptibility, resistivity and thermal expansion of the superconductor ZrB12". Phys. Rev. B. 72 (2): 024547. arXiv:cond-mat/0502193. Bibcode:2005PhRvB..72b4547L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.72.024547.

- 1 2 International Bureau of Weights and Measures. "Realising the mole Archived 2008-08-29 at the Wayback Machine.." Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ↑ physics.nist.gov/ Archived 2015-06-29 at the Wayback Machine. Fundamental Physical Constants: Avogadro Constant

- ↑ Andreas, Birk; et al. (2011). "Determination of the Avogadro Constant by Counting the Atoms in a 28Si Crystal". Physical Review Letters. 106 (3): 30801. arXiv:1010.2317. Bibcode:2011PhRvL.106c0801A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.030801.

- 1 2 de Bièvre, P.; Peiser, H.S. (1992). "'Atomic Weight'—The Name, Its History, Definition, and Units" (PDF). Pure Appl. Chem. 64 (10): 1535–43. doi:10.1351/pac199264101535. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-05-24.

- ↑ Helm, Georg (1897). "The Principles of Mathematical Chemistry: The Energetics of Chemical Phenomena". transl. by Livingston, J.; Morgan, R. New York: Wiley: 6.

- ↑ Some sources place the date of first usage in English as 1902. Merriam–Webster proposes Archived 2011-11-02 at the Wayback Machine. an etymology from Molekulärgewicht (molecular weight).

- ↑ Ostwald, Wilhelm (1893). Hand- und Hilfsbuch zur Ausführung Physiko-Chemischer Messungen [Handbook and Auxiliary Book for Conducting Physical-Chemical Measurements]. Leipzig, Germany: Wilhelm Engelmann. p. 119. From p. 119: "Nennen wir allgemein das Gewicht in Grammen, welches dem Molekulargewicht eines gegebenen Stoffes numerisch gleich ist, ein Mol, so … " (If we call in general the weight in grams, which is numerically equal to the molecular weight of a given substance, a "mol", then … )

- ↑ mole, n.8, Oxford English Dictionary, Draft Revision Dec. 2008

- ↑ "BIPM - Resolution 3 of the 14th CGPM". www.bipm.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Price, Gary (2010). "Failures of the global measurement system. Part 1: the case of chemistry". Accreditation and Quality Assurance. 15 (7): 421–427. doi:10.1007/s00769-010-0655-z. .

- ↑ Johansson, Ingvar (2010). "Metrological thinking needs the notions of parametric quantities, units, and dimensions". Metrologia. 47 (3): 219–230. Bibcode:2010Metro..47..219J. doi:10.1088/0026-1394/47/3/012.

- ↑ Cooper, G; Humphry, S (2010). "The ontological distinction between units and entities". Synthese. 187 (2): 393–401. doi:10.1007/s11229-010-9832-1.

- ↑ In particular, when the mole is used, alongside the SI unit of volume of a cubic metre, in thermodynamic calculations such as the ideal gas law, a factor of 1000 is introduced which engineering practice chooses to simplify by adopting the kilomole.

- 1 2 Himmelblau, David (1996). Basic Principles and Calculations in Chemical Engineering (6 ed.). pp. 17–20. ISBN 0-13-305798-4.

- ↑ "Lighting Radiation Conversion". Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ CIPM Report of 106th Meeting Archived 2018-01-27 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 7 April, 2018

- ↑ "Units: D". www.unc.edu. Archived from the original on 31 March 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- ↑ Jerrard, H. G. A Dictionary of Scientific Units: Including dimensionless numbers and scales. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 37. ISBN 9789401705714.

- ↑ Pratt, W. K. "Proposed new electrolytic conductivity primary standards for KCl solutions." J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol 96 (1991): 191-201.

- ↑ Shreiner, R. H.; Pratt, K.W. "Primary Standards and Standard Reference Materials for Electrolytic Conductivity, 2004" (PDF). www.nist.gov. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ↑ History of National Mole Day Foundation, Inc Archived 2010-10-23 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Happy Mole Day! Archived 2014-07-29 at the Wayback Machine., Mary Bigelow. SciLinks blog, National Science Teachers Association. October 17, 2013.

- ↑ What Is Mole Day? – Date and How to Celebrate Archived 2014-07-30 at Wikiwix, Anne Marie Helmenstine. About.com

- ↑ The Perse School (Feb 7, 2013), The Perse School celebrates moles of the chemical variety, Cambridge Network, archived from the original on 2015-02-11, retrieved Feb 11, 2015,

As 6.02 corresponds to 6th February, the School has adopted the date as their 'Mole Day'.

External links

- ChemTeam: The Origin of the Word 'Mole' at the Wayback Machine (archived December 22, 2007)