Rascians

Rascians (Latin: Rasciani, Natio Rasciana) was an exonym in the early modern period that designated Serbs of the Habsburg Monarchy, and in a wider perspective other related South Slavic ethnic groups of the Monarchy, such as the Catholic Bunjevci and Šokci (designated "Catholic Rascians"[1]). The term was derived from the "Raška" (Rascia), a medieval Serbian region and exonym of the medieval Serbian state in Western sources. Because of the large concentration of Serbs in the southern Pannonian Plain, this region was called Rascia, today encompassing territories of Serbia (Vojvodina), Croatia (Slavonia, south Baranya and west Syrmia), Hungary (north Baranya and north Bácska) and Romania (east Banat and lower Marisus).

Etymology

The demonym Latin: Rasciani, Natio Rasciana; Serbian: Раци/Raci, Расцијани/Rascijani; Hungarian: Rác, (pl.) Rácok; German: Ratzen, Raize, (pl.) Raizen, anglicized as "Rascians". The name, primarily used by Hungarians and Germans, derived from the pars pro toto "Raška" (Rascia), a medieval Serbian region.[2] The territory inhabited primarily by the Serbs in the Habsburg Monarchy was called Latin: Rascia; Serbian: Raška/Рашка; Hungarian: Ráczság,[3] Ráczország,[4] rácz tartomány,[4]; German: Ratzenland, Rezenland.

Background

The defeats at the hand of the Ottoman Empire in the late 14th century forced the Serbs to rely on the neighbouring states, especially Hungary.[5] After the Ottoman conquest of Serbian territories in 1439, Despot Đurađ Branković fled to the Kingdom of Hungary where he was given a large territory in southern Pannonia, while his son Grgur ruled Serbia as an Ottoman vassal until his removal in 1441.[6] Đurađ's daughter Katarina of Celje (1434–56) held Slavonia.[7] Having picked the losing side in the Hungarian civil war, the Branković dynasty were stripped of their estates in Hungary upon Matthias Corvinus' coronation in 1458. Left on its own, the Serbian Despotate lost the capital, Smederevo, to the Ottomans in 1459. Serbs migrated to Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Zeta, and in larger numbers to Hungary, where the immigrants were well-received. Many Hungarians left the frontier for the safer interior, leaving the southern Hungarian kingdom almost abandoned. The settlement of Serbs in Syrmia, Bačka, Banat and Pomorišje strengthened the Hungarian hold of these sparse areas, most exposed to Ottoman expansion. Following the Ottoman conquest, a large part of the Serbian nobility were killed, while what survived crossed into Hungary, bringing their subjects, including many farmer families, with them. King Matthias won over Vuk Grgurević in 1465 and proclaimed him a duke over Serbs in Syrmia and the surroundings, which intensified Serb migration; showing his military prowess with bands of Serb warriors, Vuk was proclaimed Serbian Despot in 1471 (thereby restoring the title). The Serbian Despot's army participated in the Ottoman-Hungarian Wars, penetrating into Ottoman territory, which saw large numbers of Serbs retreating with the Hungarian army. A letter of King Matthias from 12 January 1483 mentions that 200,000 Serbs had settled the Hungarian kingdom in the last four years.[8] Despot Vuk and his warriors were greatly rewarded with estates, also including places in Croatia. Also, by this time, the Jakšić family had become increasingly notable, and held estates stretching over several counties in the kingdom.[9] The territory of Vuk Grgurević (1471–85), the Serbian Despot in Hungarian service (as "Despot of the Kingdom of Rascia"), was called "Little Rascia".[10]

Since the 15th century, the Serbs made up a large percentage of the population on the territory of present-day Vojvodina. Because of this, many historical sources and maps, which were written and drawn between 15th and 18th centuries, mention the territory under the names of Rascia (Raška, Serbia) and Little Rascia (Mala Raška, Little Serbia).

History

16th century

After 1526, many Serbs (called "Rascians") settled in Slavonia.[11] In 1526–27, Jovan Nenad ruled a territory of southern Pannonia during the Hungarian throne struggle; After his death (1527), his commander Radoslav Čelnik ruled Syrmia as an Ottoman and Habsburg vassal until 1532, when he retreated to Slavonia with the Ottoman conquest.[12] Many of the Syrmian Serbs then settled the Kingdom of Hungary.[12]

A 1542 document describes that "Serbia" stretched from Lipova and Timişoara to the Danube, while a 1543 document that Timişoara and Arad being located "in the middle of Rascian land" (in medio Rascianorum).[13] At that time, the majority language in the region between Mureș and Körös was indeed Serbian.[13] Apart from Serbian being the main language of the Banat population, there were 17 Serbian monasteries active in Banat at that time.[14] The territory of Banat had received a Serbian character and was called "Little Rascia".[15]

In early 1594, the Serbs in Banat rose up against the Ottomans,[16] during the Long Turkish War (1593–1606)[17] which was fought at the Austrian-Ottoman border in the Balkans. The Serbian patriarchate and rebels had established relations with foreign states,[17] and had in a short time captured several towns, including Vršac, Bečkerek, Lipova, Titel and Bečej. The rebels had, in the character of a holy war, carried war flags with the icon of Saint Sava,[18] the founder of the Serbian Orthodox Church and an important figure in medieval Serbia. The war banners had been consecrated by Patriarch Jovan Kantul,[17] and the uprising had been aided by Serbian Orthodox metropolitans Rufim Njeguš of Cetinje and Visarion of Trebinje.[19]

17th century

In the 17th and early 18th century, the territory of Slavonia was called "Little Rascia", due to its large number of Serbs.[11] In 17th-century Habsburg usage, the term "Rascian" referred most commonly to the Serbs who lived in Habsburg territory, then more generally to Orthodox Serbs, wherever they lived, and then more generally still to speakers of Serbian or Croatian.[20] The Emperor's so-called "Invitatorium" in April 1690, for example, was addressed to Arsenije as "Patriarch of the Rascians", but Austrian court style also distinguished between "Catholic Rascians" and "Orthodox Rascians".[20] In 1695, Emperor Leopold issued a protective diploma for Patriarch Arsenije and the Serb people, whom he called "popolum Servianum" and "Rasciani seu Serviani".[21]

18th century

In official Habsburg documents from the 18th century the Serbs of Habsburg Monarchy were mentioned as Rasciani ("Rascians"), Natio Rasciana ("Rascian nation"), Illyri ("Illyrians") and Natio Illyrica ("Illyrian nation").[22]

During the Kuruc War (1703–1711) of Francis II Rakoczi, the territory of present-day Vojvodina was a battlefield between Hungarian rebels and local Serbs who fought on the side of the Habsburg Emperor. Darvas, the prime military commander of the Hungarian rebels, which fought against Serbs in Bačka, wrote: We burned all large places of Rascia, on the both banks of the rivers Danube and Tisa.

1801–48

When the representatives of the Vojvodinian Serbs negotiated with the Hungarian leader Lajos Kossuth in 1848, they asked him not to call them Raci, because they regard this name insulting, since they had their national and historical endonym – Serbs.

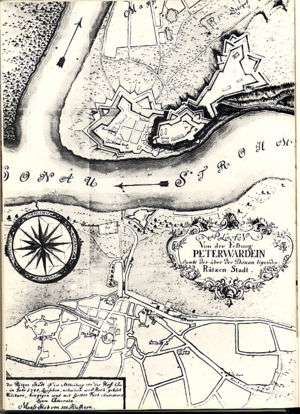

The initial name of the city of Novi Sad, Ratzen Stadt (Rascian/Serb City) derived from the name. The Tabán quarter of Budapest was also called Rácváros in the 18th-19th centuries due to its significant Serb population.

Since the 19th century, the term Rascians is no longer used.

Religion

After the Great Serb Migration, the Eparchy of Karlovac and Zrinopolje was established in 1695, the first metropolitan being Atanasije Ljubojević, the exiled metropolitan of Dabar and Bosnia.

Military

Legacy

There is a Hungarian surname, Rác.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Habsburg Serbs. |

References

- ↑ Glasnik Srpskog istorijsko-kulturnog društva "Njegoš". Njegoš. 1985.

У другој су биле све могуће нације, међу њима и „католички Раци", тј. Буњевци и Шокци.

- ↑ Kalić 1995.

- ↑ Rascia 1996.

- 1 2 Летопис Матице српске. 205-210. У Српској народној задружној штампарији. 1901. p. 20.

... и да je Иза- бела ту у области, Koja ce звала Cpoiija (Ráczország, rácz tartomány), за поглавара поставила 1542 ПетровиКа: Из AuaÄHJeea дела видимо, да je ПетровиК управл>ао банат- ским и сремским Србима, да je био велик ...

- ↑ Ivić 1914, p. 5.

- ↑ Новаковић, Стојан (1972). Из српске историjе. Matica srpska. pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Serbian Orthodox Church: Its Past and Present. 8. Serbian Patriarchy. 1992. p. 87.

- ↑ Henry Clifford Darby (1968). Short History of Yugoslavia. CUP Archive. p. 103.

- ↑ Ivić 1914, pp. 5–17.

- ↑ Sima Lukin Lazić (1894). Kratka povjesnica Srba: od postanja Srpstva do danas. Štamparija Karla Albrehta. p. 149.

- 1 2 Lazo M. Kostić (1965). Obim Srba i Hrvata. Logos. p. 58.

- 1 2 Летопис Матице српске. 351. У Српској народној задружној штампарији. 1939. p. 114.

- 1 2 Posebna izdanja. 4–8. Naučno delo. 1952. p. 32.

- ↑ Rascia 1996, p. 2.

- ↑ Mihailo Maletić; Ratko Božović (1989). Socijalistička Republika Srbija. 4. NIRO "Književne novine". p. 46.

- ↑ Rajko L. Veselinović (1966). (1219-1766). Udžbenik za IV razred srpskih pravoslavnih bogoslovija. (Yu 68-1914). Sv. Arh. Sinod Srpske pravoslavne crkve. pp. 70–71.

Устанак Срба у Банату и спалмваъье моштийу св. Саве 1594. — Почетком 1594. године Срби у Банату почели су нападати Турке. Устанак се -нарочито почео ширити после освадаъьа и спашьиваъьа Вршца од стране чете -Петра Маджадца. Устаници осводе неколико утврЬених градова (Охат [...]

- 1 2 3 Mitja Velikonja (5 February 2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 75–. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- ↑ Nikolaj Velimirović (January 1989). The Life of St. Sava. St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-88141-065-5.

- ↑ Editions speciales. Naučno delo. 1971.

Дошло ]е до похреаа Срба у Ба- нату, ко]и су помагали тадаппьи црногоски владика, Херувим и тре- бюьски, Висарион. До покрета и борбе против Ту рака дошло ]е 1596. године и у Цр- иэ] Гори и сус]едним племенима у Харцеговгаш, нарочито под утица- ]ем поменутог владике Висариона. Идупе, 1597. године, [...] Али, а\адика Висарион и во]вода Грдан радили су и дал>е на организован>у борбе, па су придобили и ...

- 1 2 Noel Malcolm, Kosovo - A Short History, Pan Books, London, 2002, page 145.

- ↑ Radoslav M. Grujić; Vasilije Krestić (1989). Апологија српскога народа у Хрватској и Славонији. Просвета.

Цар Леополд I издао je 1695. год. заштитну диплому за митрополита-патриарха ApcenHJa III MapHojeBHha и срйски народ (»popolum Servianum«, »Rasciani seu Serviani populi«, »populo Rasciano seu Serviano« итд.) y йожешком и ...

- ↑ Serbski li͡etopis za god. ... Pismeny Kral. Sveučilišta Peštanskog. 1867. pp. 250–.

Sources

- Books

- Ivić, Aleksa (1929). Историја Срба у Војводини. Novi Sad: Matica srpska.

- Ivić, Aleksa (1914). Историја Срба у Угарској: од пада Смедерева до сеобе под Чарнојевићем (1459-1690). Zagreb: Привредникова.

- Popović, Dušan J. (1957). Srbi u Vojvodini (1): Od najstarijih vremena do Karlovačkog mira 1699. Matica srpska.

- Popović, Dušan J. (1959). Srbi u Vojvodini (2): Od Karlovačkog mira 1699 do Temišvarskog sabora. Matica srpska.

- Tutorov, Milan (1991). Mala Raška a u Banatu. Zrenjanin.

- Journals

- "Rascia, Časopis o Srbima u Vojvodini". 1 (1). Vršac. May 1996.

- Kalić, Jovanka (1995). "Rascia - The Nucleus of the Medieval Serbian State". Faculty of Geography. Archived from the original on 2014-01-15.

- Gavrilović, Vladan, and Dejan Mikavica. "Владавина права и грађанска равноправност срба у Хабзбуршкој монархији 1526-1792." Teme-Časopis za Društvene Nauke 04 (2013): 1643-1654.

- Lemajić, Nenad (2016). "EARLY CONTACTS BETWEEN THE SERBS AND THE HABSBURGS (TO THE BATTLE OF MOHACS)". ISTRAŽIVANJA, Journal of Historical Researches. 25: 73–87.

Maps

Map from 1590, in which name Rascia is located in Banat

Map from 1590, in which name Rascia is located in Banat Map from 1609, showing name Rascia in Slavonia

Map from 1609, showing name Rascia in Slavonia Map from 1643-50, showing name Rascia in Slavonia

Map from 1643-50, showing name Rascia in Slavonia Map from 1645, in which name Rascia is located in Banat

Map from 1645, in which name Rascia is located in Banat Map from the first half of the 17th century, in which name Rascia is located in Banat

Map from the first half of the 17th century, in which name Rascia is located in Banat

- Map of Banat with the name Rasciani

Map of Novi Sad (Ratzen Stadt) from 1745

Map of Novi Sad (Ratzen Stadt) from 1745