Pons, Count of Tripoli

| Pons | |

|---|---|

His seal | |

| Count of Tripoli | |

| Reign | 1112–1137 |

| Predecessor | Bertrand |

| Successor | Raymond II |

| Born | c. 1098 |

| Died | 25 March 1137 (aged 38–39) |

| Spouse | Cecile of France |

| Issue |

Raymond II Philip Agnes |

| House | House of Toulouse |

| Father | Bertrand of Tripoli |

| Religion | Catholicism |

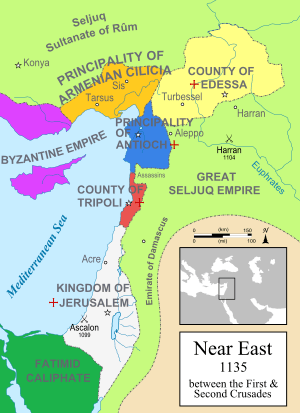

Pons (c. 1098 – 25 March 1137) was count of Tripoli from 1112 to 1137. He was still a minor when his father, Bertrand, died in 1112. He swore fealty to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos in the presence of a Byzantine embassy. His advisors sent him to Antioch to be educated in the court of Tancred of Antioch, thus putting an end to the hostilities between the two crusader states. Tancred granted four important fortresses to Pons in the Principality of Antioch. On his deathbed, Tancred also arranged the marriage of his wife, Cecile of France, and Pons. Pons closely cooperated with Tancred's successor, Roger of Salerno, against the Muslim rulers in the 1110s.

He refused obedience to Baldwin II of Jerusalem in early 1122, but their vassals soon mediated a reconciliation between the two rulers. Pons was one of the supreme commanders of the crusader troops during the successful siege of Tyre in 1124. He supported Alice of Jerusalem, the dowager princess of Antioch, against her brother-in-law, Fulk, King of Jerusalem, in late 1132, but they could not prevent Fulk from taking control of Antioch. A year later, Pons could only defend his county against Imad ad-Din Zengi, atabeg of Mosul, with Fulk's assistance.

Native Christians captured Pons during a campaign of Bazwāj, the mamluk (or slave) commander of Damascus, against Tripoli in March 1137. His captors handed him over to Bazwāj who had him killed. The County of Tripoli developed into a fully independent crusader state during Pons' reign who united his inherited lands (that his father had held in fief of the kings of Jerusalem) with territories located in the Principality of Antioch.

Early life

Pons' father, Bertrand, was the eldest son of Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse, but Bertrand's legitimacy was dubious because his parents were closely related.[1][2] The identity of Pons' mother is uncertain.[3] The contemporaneous Orderic Vitalis stated that Helie of Burgundy (a daughter of Odo I, Duke of Burgundy) was his mother, but William of Malmesbury wrote that Pons had been born to an unnamed niece of the powerful Matilda of Tuscany.[3] The year of Pons' birth is also uncertain.[4] The contemporaneous Muslim author, Ibn al-Qalanisi, noted that Pons was a "small boy" when his father died in early 1112.[4] William of Malmesbury and William of Tyre wrote that Pons had been an "adolescent" when he succeeded his father.[4] Available data, therefore, suggest that Pons was born around 1098, according to historian Kevin James Lewis.[4]

Bertrand renounced the County of Toulouse in favor of his infant half-brother, Alfonso Jordan, in the summer of 1108.[5][6] He soon sailed to Syria to claim the lands that his father had conquered around Tripoli.[5][7] Pons most probably accompanied his father.[4] He signed one of Bertrand's charters issued in Tripoli in 1110 or 1111.[4]

Reign

Minority

Pons was still a minor when his father died on 3 February 1112.[8][9] Anna Comnena recorded that Bishop Albert of Tripoli wanted to keep the money that a Byzantine embassy had deposited with Pons's father and the bishop.[10] Lewis says, the dispute evidences that the bishop exerted a strong influence on the government during Pons's minority.[11] The money was returned to the Byzantines only after they threatened to impose a blockade on Tripoli.[11][12] Pons could only keep the gold and other valuable objects which had explicitly been promised his father as a personal gift.[13] The Byzantines also persuaded Pons to swear fealty to the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, similarly to his grandfather and father.[14][15]

His "guardians and lords" concluded an agreement with Tancred of Antioch, making Pons "one of Tancred's knight", according to Ibn al-Qalanisi.[4] Historian Jean Richard associated the "guardians and lords" with the most influential noblemen of the County of Tripoli who ruled the county on the minor count's behalf.[16] Their decision helped to reconcile Antioch's Norman and Tripoli's Occitan crusaders, who had fallen out during the Siege of Antioch.[17][18] The conflict with the Byzantines also contributed to the rapprochement between Tripoli and Antioch.[14]

Tancred granted Tortosa (now Tartus in Syria), Maraclea, Safita and Hisn al-Akrad—which had been claimed by the counts of Tripoli—to Pons in fief.[19][20] For Pons held his inherited lands in fief of the kings of Jerusalem, Tancred's grant contributed to the development of Tripoli into an autonomous crusader state.[21] Tancred died in December 1112, but only after ordering his wife, Cecile of France, be engaged to Pons.[20][22] William of Malmesbury wrote that the dying prince arranged the marriage because he was convinced that Pons would be a successful military leader.[20]

Pons remained in Antioch during the first months or years of the rule of Tancred's successor, Roger of Salerno.[23] Baldwin I of Jerusalem sent envoys to Antioch to seek the assistance of Roger and Pons against Mawdud, the Seljuk atabeg of Mosul, who had invaded the Kingdom of Jerusalem in late June 1113.[24] However, Baldwin did not wait until their arrival and attacked the invaders near Tiberias, but his army was defeated on 28 June.[4][25] Pons accompanied Roger during the campaign and they sharply criticized Baldwin for his impatience after their arrival.[4]

Cooperation

Walter, Chancellor of Antioch, who wrote a chronicle about the history of the principality, never refers to Pons's presence in Antioch, implying that Pons had reached the age of majority and returned to Tripoli before 29 November 1114 (which is the starting date of Walter's narration).[23] Pons was certainly in Tripoli when Bursuq ibn Bursuq of Hamadan invaded Antioch in 1115, because Roger of Salerno sent envoys from Antioch to Tripoli to seek his assistance.[23] Walter of Chancellor recorded that Pons marched north to aid Roger only after Baldwin II of Jerusalem had ordered him to join his campaign, showing that Pons still acknowledged the suzerainty of the king.[26] After their united armies reached Apamea, Bursuq lifted the siege of the Antiochene fort of Kafartab and retreated without fighting.[27] Baldwin and Pons soon returned to their countries, enabling Bursuq to return and capture Kafartab.[28] Roger of Salerno attacked the invaders before Baldwin and Pons came back, and defeated Bursuq on 14 September.[29][30]

Ilghazi, the Ortoquid ruler of Mardin, invaded Antioch at the end of May 1119.[31] Bernard, the Latin Patriarch of Antioch, convinced Roger to again seek assistance from Baldwin II and Pons.[31][32] However, Roger could not wait until their arrival and launched a counter-attack against Ilghazi at the head of the whole army of his principality.[33][34] Roger died fighting and his army was annihilated on 28 June.[35][36] Ilghazi tried to prevent Baldwin and Pons from reaching Antioch, but Baldwin entered the town without resistance, and Pons, who arrived a day later, warded off Ilghazi's attack in early August.[37] Baldwin was acknowledged as the ruler of Antioch until its absent prince, Bohemond II, came of age.[38][39]

Conflicts and alliances

Baldwin's acquisition of Antioch made him the most powerful monarch of the crusader states which annoyed Pons.[40] Neither Pons nor the bishops of his county attended the synod which was held on 23 January 1120 at Nablus, although all prelates and secular lords of the Kingdom of Jerusalem were present at the assembly.[41] He openly refused obedience to the king in early 1122.[42][43] Baldwin mustered his army and marched towards Tripoli, taking the True Cross from Jerusalem with him.[42] To avoid an armed conflict, the two rulers' vassals mediated a reconciliation, making Baldwin and Pons "friends", according to Fulcher of Chartres' report.[44]

Balak, the Ortoquid ruler of Harran, captured Baldwin II of Jerusalem on 18 April 1123.[45][46] During his captivity, a Venetian fleet under the command of the Doge, Domenico Michele, arrived at Acre.[47][48] Taking advantage of the presence of a sizeable army from Europe, the leaders of the Kingdom of Jerusalem decided to capture Tyre, one of the two last Fatimid ports on the western coast of the Mediterranean Sea.[46][49] They laid siege to the town on 16 February 1124.[48]

The Jerusalemite nobles sent envoys to Pons, urging him to join the siege.[50] Pons hurried to the town, accompanied by a large retinue, damaging the self-confidence of the defenders of the town, according to William of Tyre.[50][51] Although Fulcher of Chartres and William of Tyre emphasized that Pons "remained always obedient" to Gormond, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, and other Jerusalemite lords during the siege, their narration actually evidence that Pons was regarded as one of the supreme commanders of the Christian army.[50] He led the Christian troops' successful attack against Toghtekin, the Emir of Damascus, who tried to relieve the besieged town.[50] He was chosen to confer knighthood to the messenger of Joscelin I of Edessa who had brought the severed head of Balak (Baldwin's captor) to the crusaders' camp.[50] After the capture of Tyre on 7 July,[48] Pons' banner was one of the three flags erected over the towers of the town.[52]

Pons' activities in the late 1120s and early 1130s are poorly documented.[53] He supported Baldwin II against Bursuq of Bursuq, who had invaded Antiochene territory and captured the fortress of Kafartab in May 1125.[53][54] The united forces of Jerusalem, Antioch, Tripoli and Edessa defeated Bursuq at Zardana on 11 June, forcing him to lift the siege of the fort.[53][55] Next year he sought assistance from the king in attacking Rafaniya (an important castle once held by Pons' grandfather).[56][57] They besieged the fortress for 18 days and captured it on 31 March 1126.[58][59] Pons also participated in an unsuccessful campaign against Damascus in November 1129.[60]

Sedition

Relationship between the crusader states became tense after Baldwin II died on 21 August 1131.[61] Baldwin's successor, Fulk of Anjou, seized the estates of the local lords in both Jerusalem and Antioch and granted them to his own partisans.[62] His sister-in-law, Alice, the dowager princess of Antioch wanted to take control of the government of Antioch and formed an alliance with Pons and Joscelin II of Edessa in the summer of 1132.[63][64] According to William of Tyre, Alice bribed Pons into the alliance.[65] The Antiochene lords who opposed Alice asked Fulk to intervene, but Pons refused the king passage through Tripoli, forcing Fulk to avoid the county and travel by sea to the Antiochene port of Saint Symeon (now Samandağ in Turkey).[66][67]

Pons hurried to Antioch and launched a series of attacks against Fulk and his allies from the Antiochene fortesses Chastel Rouge and Arzghan (two castles forming the dowry of his wife).[68] He captured the fort at Salamiyah.[69] Fulk attacked Pons near Chastel Rouge in late 1132.[69] Pons suffered a heavy defeat, with many of his retainers being captured in the battlefield, but he could fled.[69][70] His soldiers were taken in chain to Antioch where they were either imprisoned or executed.[69] Pons lost Chastel Rouge and Arzghan, but Fulk did not restored the suzerainty of the kings of Jerusalem over Tripoli.[71]

Last years

Pons renounced the estates that he held in the county of Velay (in France) in favor of the bishop of Le Puy in 1132.[72] He had the ra'īs (or native chief) of Tripoli murdered for unknown reasons in 1132 or 1133.[73] For the execution of a native chief at a crusader ruler's order was an unprecedented act, Lewis argues that it was the sign of growing unrest among the local population.[73] Actually, the Nizari strengthened their hold of the mountainous region along the northern border of the county in the 1130s.[74]

Imad ad-Din Zengi, atabeg of Mosul, invaded the County of Tripoli, plundering the capital and the neighboring region in 1133.[75] Pons wanted to stop the invaders near Rafaniya, but his army was almost annihilated.[75] After the catastrophic defeat, he fled first to Montferrand, and soon to Tripoli, while Zengi laid siege to the fort of Montferrand.[76] Pons sought Fulk's assistance and the arrival of the Jerusalemite army forced Zengi to lift the siege and to withdraw his troops from the county.[70][77]

In March 1137, Bazwāj, the mamluk commander of Damascus, launched a military campaign against Tripoli, reaching Pilgrims' Mount near the town.[78] Pons rode out of Tripoli to meet the enemy, but he suffered a defeat.[78] He fled to the nearby mountains, but local Christians—according to Lewis, most probably Jacobites or Nestorians[79]—captured and handed him over to Bazwāj who had him killed on 25 March 1137.[80][81]

Family

Pons married Tancred of Antioch's widow, Cecile of France, in the presence of Baldwin I of Jerusalem in Tripoli in the summer of 1115, according to Albert of Aix.[82][20] Being a daughter of Philip I of France and Bertrade de Montfort, she was the half-sister of Fulk of Jerusalem.[83] The eldest son of Pons and Cecile, Raymund, was allegedly born in the late 1110s, because he was an "adolescent" when he succeeded Pons.[84] Pons' younger son, Philip, was last mentioned in the 1140s, but the details of his life are unknown.[85] The only daughter of Pons and Cecile, Agnes, was married to Raynald II Mazoir who was a prominent Antiochene nobleman.[86]

References

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 26, 28, 73.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 61.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Lewis 2017, p. 76.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 65.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 34.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 35, 37.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 72, 76.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 31.

- ↑ Lilie 1993, pp. 87-88.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 78.

- ↑ Lilie 1993, p. 88.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 137-138.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 81.

- ↑ Lilie 1993, pp. 68, 88.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 77-78.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 124-125.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 80-81.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 102.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis 2017, p. 82.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Lewis 2017, p. 77.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 32.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 84.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 131.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 132.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 33.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 148.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 122.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 149.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 122-123.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 149-150.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 123.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 152.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 125.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 94.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 92-93.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 93.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 160.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 93, 96.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 161-162.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 97.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 166-167.

- 1 2 3 Lock 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 167-168.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis 2017, p. 98.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 96.

- 1 2 3 Lewis 2017, p. 100.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 100-101.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 174.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 101.

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 101-102.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 102.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 103.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 152.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 104.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 105-106.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 152-153.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 107-108.

- 1 2 3 4 Lewis 2017, p. 108.

- 1 2 Lock 2006, p. 41.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 108, 112.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 79-80, 117.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 116.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 114-115.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 112.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 112-113.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 113.

- 1 2 Lewis 2017, p. 117.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 134.

- ↑ Lewis 2006, p. 43.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 202.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 103.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 113.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 130.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, pp. 109, 183.

- ↑ Lewis 2017, p. 109.

Sources

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Crusader States. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9.

- Lewis, Kevin James (2017). The Counts of Tripoli and Lebanon in the Twelfth Century: Sons of Saint-Gilles. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-5890-2.

- Lilie, Ralph-Johannes (1993). Byzantium and the Crusader States 1096-1204. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820407-8.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 9-78-0-415-39312-6.

- Runciman, Steven (1989). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100-1187. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06163-6.

Further reading

- Richard, Jean (1945). Le comté de Tripoli sous la dynastie toulousaine (1102-1187) [The County of Tripoli under the Dynastie of Toulouse] (in French). P. Geuthner. ISSN 0768-2506.

Pons, Count of Tripoli Born: c. 1098 Died: 25 March 1137 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Bertrand |

Count of Tripoli 1112–1137 |

Succeeded by Raymond II |