Apamea, Syria

|

Greek: Ἀπάμεια Arabic: آفاميا | |

View of Apamea ruins | |

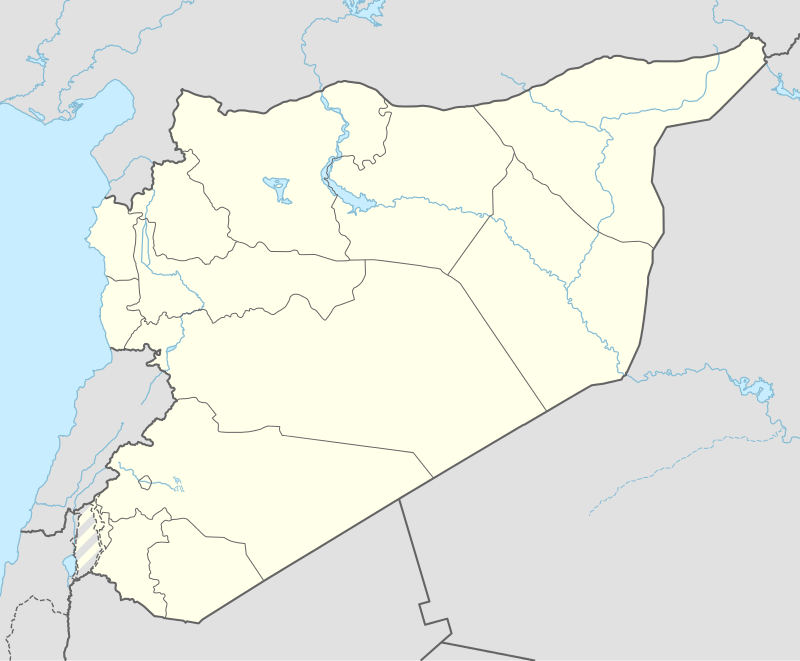

Shown within Syria | |

| Location | Hama Governorate, Syria |

|---|---|

| Region | Ghab plain |

| Coordinates | 35°25′05″N 36°23′53″E / 35.418°N 36.398°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Builder | Seleucus I Nicator |

| Founded | ca. 300 BC |

| Abandoned | 13th century |

| Cultures | Seleucid, Roman, Byzantine, Arab |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | ruins |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Apamea (Greek: Ἀπάμεια, Apameia; Arabic: آفاميا, Afamia), on the right bank of the Orontes River, was an ancient Greek and Roman city. It was the capital of Apamene under the Macedonians,[1] became the capital and Metropolitan Archbishopric of late Roman province Syria Secunda, again in the crusader time and since the 20th century a quadruple Catholic titular see.

Amongst the impressive ancient remains, the site includes the Great Colonnade which ran for nearly 2 km (1.2 mi) making it among the longest in the Roman world and the Roman Theatre, one of the largest surviving theatres of the Roman Empire with an estimated seating capacity in excess of 20,000.

The site is about 55 km (34 mi) to the northwest of Hama, Syria, overlooking the Ghab valley.

History

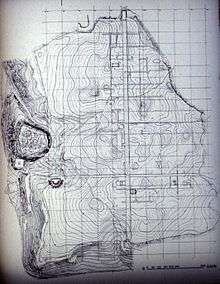

After the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great and the subsequent wars between his generals, Apamea fell under the command of the former Macedonian general Seleucus from about 312 BC. From about 300 BC Apamea was fortified and established as a city by Seleucus who named it after his Bactrian wife, Apama daughter of the Sogdian warlord Spitamenes (not his mother, as Stephanus asserts; compare Strabo, p. 578). The site was enclosed in a loop of the Orontes which, with the lake and marshes, gave it a peninsular form whence its other name of Cherronêsos. It was located at a strategic crossroads for Eastern commerce and became one of the four cities of the Syrian tetrapolis. Seleucus also made it a military base with 500 elephants, and an equestrian stud with 30,000 mares and 300 stallions.

After 142 BC, the pretender Diodotus Tryphon made Apamea the base of his operations.[2]

Q. Aemilius Secundus[3] did a population survey in AD 6, in which he counted "117,000 hom(ines) civ(ium)" – a figure that has been interpreted as giving a total population of either 130,000 or 500,000, depending on methods used.[4]

In 64 BC Pompey marched south from his winter quarters probably at or near Antioch and razed the fortress of Apamea when the city was annexed to the Roman Republic.[5] In the revolt of Syria under Q. Caecilius Bassus, it held out against Julius Caesar for three years till the arrival of Cassius in 46 BC. (Dion. Cass. xlvii. 26–28; Joseph. Bel. Jud. i. 10. § 10.) On the outbreak of the Jewish War, the inhabitants of Apamea spared the Jews who lived in their midst and would not suffer them to be murdered or led into captivity (Josephus, Bell. Jud. ii. 18, § 5). Apamea was briefly captured in 40 BC by the Pompeian-Parthian forces.

Much of Apamea was destroyed in the 115 AD earthquake, but was subsequently rebuilt.

From 218 until 234 AD the legion II Parthica was stationed in Apamea, when it abandoned support of the usurper Macrinus to the emperor and sided with Elagabalus' rise to the purple who then defeated Macrinus in the Battle of Antioch.[6]

Destroyed by Chosroes I in the 6th century, it was partially rebuilt and known in Arabic as Famia or Fâmieh, and destroyed by an earthquake in 1152.[7] In the Crusades it was still a flourishing and important place and was occupied by Tancred. (Wilken, Gesch. der Ks. vol. ii. p. 474; Abulfeda, Tab. Syr. pp. 114, 157.)

Both the Jerusalem Targumim considered the city of Shepham (Num. xxxiv. 11) to be identical with Apamea. Since Apamea virtually belonged to Rabbinic Palestine, the first-fruits brought by Ariston from that town were accepted for sacrifice in Jerusalem (Mishnah Ḥal. iv. 11).

Remains

Many remains of the ancient acropolis are still standing, consisting probably of the remains of the temples of a highly ornamental character and of which Sozomen speaks (vii. 15); it is now enclosed in ancient castle walls called Kalat el-Mudik (Kŭlat el-Mudîk); the remainder of the ancient city is to be found in the plain.

The most significant collection of objects from the site, including many significant architectonic and artistic objects, that can be seen outside of Syria are in Brussels at the Cinquantenaire Museum.

As a result of the recent civil war in Syria, the ancient city has been damaged and looted by treasure hunters.[8][9] In April 2017, Al-Masdar News published satellite photographs revealing the site was covered in hundreds of holes dug by treasure hunters seeking ancient artifacts.[10]

Great Colonnade

The Great Colonnade was situated along the main avenue of Apamea and ran for nearly 2 kilometres (1.2 mi), making it among the longest in the Roman world. It was rebuilt after the original, dating from the Seleucid Empire, was devastated along with the rest of Apamea in the 115 AD earthquake. Reconstruction started immediately and over the course of the second century the city was completely rebuilt, starting with the Great Colonnade.[11] The colonnade was aligned along the north-south axis, making up the city's "cardo maximus". Starting at the city's north gate, the colonnade ran in an uninterrupted straight line to the south gate. The northern third of the colonnade's stretch is marked by a monumental votive column that stood opposite the baths.[12] The colonnade passed through the centre of the city and several important buildings were clustered around it, including the baths, the agora, the Temple of Tyche, the nymphaeum, the rotunda, the atrium church and the basilica.[13] On either side of the street a 6.15 metres (20.2 ft) wide colonnade ran its full length. The columns were 9 metres (30 ft) high and 0.9 metres (2 ft 11 in) in diameter. They stood on square bases of 1.24 m on a side and 0.47 m high. The columns display two main designs: plain and distinctive spiral-flutes. Archaeologist Jean Lassus argues that the former dates back to the Trajanic period, while the latter to that of Antoninus Pius.[14] The colonnade's porticoes were paved with extensive mosaics along the full stretch of the colonnade.[12]

Under the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, several parts of the colonnade were restored. The street was narrowed to 12 m by adding a walkway on either side. Several stretches of the street had their Roman pavement replaced with a new pavement made of squared blocks of limestone. The new pavement also covered a completely overhauled drainage system. Justinian's changes included erecting a monumental tetrastylon made up of four 9 m high columns with a metre-high capitals.[15] The city, was however, later sacked by the Sasanians under Adarmahan.[16]

A reconstructed section of the colonnade be seen in the Brussels Cinquantenaire Museum.

Roman theatre

Originally built as a Hellenistic style theatre in the early Seleucid Empire, the theatre was expanded and remodelled in the early Roman period,[17] when the main stage and entrances were reorganized in a more typical Roman fashion. The 115 Antioch earthquake caused severe damage to the structure. It was rebuilt soon-after under patronage from both Trajan and Hadrian. The theatre was further expanded in the first half of the third century CE.[18] Under the Byzantine Empire the theatre's drainage basin was restructured and a "qanat" was built through the middle of the lower stage. By the late Byzantine period the theatre had stopped serving as a centre for theatrical performances. However, the theatre and its "qanat" continued to play an important role as a water resource during the Byzantine and Islamic periods.[19] The theatre was built into a steep hill overlooking the Orontes River valley.[20]

The theatre, along with the one at Ephesus, is one of the largest surviving theatres of the Roman Empire with an estimated seating capacity in excess of 20,000. The only other known theatre that is considerably larger was the Theatre of Pompey in Rome.[21] Much of the theatre structure is in ruins due to architectural collapses and extensive quarrying in later epochs,[22] and only one-eighth of the site has been exposed so far.[21] One of the main features at the theatre is its water basin and the elaborate Roman piping system used in it. The recently excavated terracotta system is located along the eastern ground entrance and is well preserved.[23]

Great hunting mosaic

This mosaic, now in the Cinquantenaire Museum, Brussels, was discovered in 1935 in the reception room of what was probably the palace of the Roman governor of the province of Syria Secunda. Its area is 120 m².

The great mosaic dates from 415-420 AD and is amongst the most prestigious of this type of composition. It is comparable technically and thematically with mosaics in the Palace of the Byzantine emperors in Constantinople, of the same period.

An inscription at the entrance states: "During the most beautiful Apellion, the triclinium was rebuilt in the month Gorpiaios, third indict, in the year 851" (September, 539 AD).

Ecclesiastical history

- TO ELABORATE

A 6th-century Notitia Episcopatuum shows that Apamea in Syria was the Metropolitan see, in the sway of Patriarchate of Antioch, for seven suffragan dioceses: Arethusa, Balanea, Epiphania in Syria, Larissa in Syria, Mariamme, Raphanea and Seleucobelus,[24] until the 7th century Arab conquest ended both Byzantine rule and the archbishopric, while Jacobites established their own see under Muslim rule, with at least nine bishops, who are not counted in the apostolic succession.

It became a Latin archiepiscopal see again at the 13th century Crusades[25][26] now under the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem.

No longer a residential archdiocese, it became listed by the Catholic Church as a fourfold titular see [27] in the Latin and three Eastern Catholic rites (of Metropolitan rank except the merely episcopal Maronite see).

Titular Latin see

The diocese was nominally restored as a Latin Catholic Metropolitan titular archbishopric (the highest rank) in the 19th century as Apamea (until 1925 also called Haman/ Hamous), renamed Apamea in Syria / Apamen(us) in Syria (Latin adjective) in 1933.

It is vacant since decades, having had the following incumbents, so far of the fitting Archiepiscopal rank :

- Antonio Briganti (1882.10.02 – death 1906) as emeritate, previously Bishop of Orvieto (Italy) (1871.10.27 – 1882.10.02)

- Paolo Pappalardo (Italian) (1948.08.07 – 1966.08.06) as papal diplomat : Apostolic Internuncio to Iran (1948.08.07 – 1953.03.19), Apostolic Internuncio to Syria (1953.03.19 – retired 1958)

- Eris Norman Michael O’Brien (1966.11.20 – death 1974.02.28) as emeritate; formerly Titular Bishop of Alinda (1948.02.05 – 1951.01.11) as Auxiliary Bishop of Archdiocese of Sydney (Australia) (1948.02.05 – 1951.01.11), Titular Archbishop of Cyrrhus (1951.01.11 – 1953.11.16) as Coadjutor Archbishop of Canberra and Goulburn (Australia) (1951.01.11 – 1953.11.16) and succeeded as Archbishop of Canberra and Goulburn (1953.11.16 – 1966.11.20).

Titular Maronite see

Established in 1970 as Maronite Titular bishopric of Apamea in Syria (of the Maronites), of the lowest (Episcopal) rank.

It is vacant since decades, having had the following incumbents of both the fitting Episcopal (lowest) rank and the intermediary (archiepiscopal) rank :

- Titular Archbishop Ignace Abdo Khalifé, Jesuits (S.J.) (1970.03.20 – 1973.06.25) as Auxiliary Bishop of Antioch of the Maronites (Lebanon) (1970.03.20 – 1971) and as Patriarchal Vicar of Antioch of the Maronites (1971 – 1973.06.25), later Archbishop-Bishop of Saint Maron of Sydney of the Maronites (Australia) (1973.06.25 – retired 1990.11.23); died 1998

- Titular Archbishop Antoine Joubeir (1975.07.12 – 1977.08.04) as Auxiliary Bishop of Tripoli of the Maronites (Lebanon) (1975.07.12 – 1977.08.04), later succeeding as Archeparch (Archbishop) of Tripoli of the Maronites (1977.08.04 – retired 1993.07.02); died 1994

- Titular Bishop Paul-Emile Saadé (1986.05.02 – 1999.06.05) as Auxiliary Bishop of Antioch of the Maronites (Lebanon) (1986.05.02 – 1987)and as Patriarchal Vicar of Antioch of the Maronites (Lebanon) (1987 – 1995); later Eparch (Bishop) of Batroun of the Maronites (Lebanon) (1999.06.05 – retired 2012.01.16).

Titular Melkite see

Established in 1980 as Melkite Metropolitan Titular archbishopric of Apamea in Syria (of the Melkites).

It is vacant, having had a single incumbent :

- Titular Archbishop Jean Mansour, Society of Missionaries of Saint Paul (M.S.P.) (1980.08.19 – 2006.11.17)

Titular Syrian see

Established in 1920 as Syrian (Syriac) Titular Metropolitan Titular archbishopric of Apamea in Syria (of the Syrians).

It is vacant since decades, having had the following incumbents of the Archiepiscopal (intermediary) rank :

- Titular Archbishop Clemente Micara (1920.05.07 – 1946.02.18) as papal diplomat: Apostolic Nuncio (ambassador) to Czechoslovakia (1920.05.07 – 1923.05.30), Apostolic Nuncio to Belgium (1923.05.30 – 1946.02.18), Apostolic Internuncio to Luxembourg (1923.05.30 – 1946.02.18), created Cardinal-Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva (1946.02.22 – 1946.06.13), promoted Cardinal-Bishop of Velletri (1946.06.13 – 1965.03.11), also Cardinal-Priest of S. Maria sopra Minerva in commendam (1946.06.13 – 1965.03.11), Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of Religious (1950.11.11 – 1953.01.17), Pro-Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of Rites (1950.11.11 – 1953.01.26), President of Pontifical Commission for Sacred Archaeology (1951 – 1965.03.11), became Cardinal Vice-Dean of Sacred College of Cardinals (1951.01.13 – 1965.03.11), Vicar General for the Vicariate of Rome (Italy) (1951.01.26 – 1965.03.11), Camerlengo of Sacred College of Cardinals (1960 – 1961), Apostolic Administrator of Ostia (Italy) (1962 – 1965.03.11)

- Titular Archbishop Clément Ignace Mansourati (1963.07.06 – 1982.08.11).

The Holy Great Martyr Procopius (Procopius of Scythopolis) is related to Apamea: "on the way to Egypt, near the Syrian city of Apameia, Neanius had a vision of the Lord Jesus, just as once formerly had happened with Saul on the road to Damascus" (source: the life of the saint, at https://www.holytrinityorthodox.com/calendar/los/July/08-02.htm)

Notable residents

- Al-Muqtana (11th-century Ismāʿīlī Governor and a founder of the Druze Faith, the primary exponent of the Divine call and author of several of the Epistles of Wisdom.) [28][29]

- Archigenes (Greek physician)

- Aristarchus of Thessalonica (bishop, one of the Seventy Apostles)

- Evagrius Scholasticus (6th-century historian)

- Iamblichus of Chalcis (Neo-Platonist philosopher)

- Junias (1st-century bishop)

- Numenius of Apamea (2nd century philosopher)

- Polychronius (bishop, and brother of Theodore of Mopsuestia)

- Posidonius (Greek philosopher and author, 2nd-1st Century BCE)

- Sextus Varius Marcellus (3d-century Roman Equestrian and later governor of Numidia. Husband of Julia Soaemias and father of Roman emperor Elagabalus)

- Theodoret (5th-century bishop)

See also

- Qalaat al-Madiq (modern city)

- List of Catholic dioceses in Syria

- Apamea (Babylonia)

References

- ↑ (Stephanus of Byzantium s. v.; Strabo xvi. p. 752; Ptolemy v. 15. § 19; Festus Avienus, v. 1083; Anton. Itin.; Hierocles)

- ↑ Strab. l. c.

- ↑ http://www.livius.org/pictures/lebanon/beirut-berytus/tombstone-of-q-aemilius-secundus/

- ↑ David Kennedy (20 Nov 2013). Gerasa and the Decapolis. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 111.

- ↑ Josephus 'Ant. xiv. 3. § 2

- ↑ Apamea in Syria in the Second and Third Centuries A.D. Jean Ch. Balty The Journal of Roman Studies Vol. 78 (1988), pp. 91-104 Published by: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies DOI: 10.2307/301452 Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/301452

- ↑

- ↑ Rebecca Ananda (26 May 2015). "The History and Culture I Saw in Syria Is Now Scarred by War". Huffington Post.

- ↑ Andrew Lawler, "Satellites track heritage loss across Syria and Iraq", Science, Year 2014, Volume 346, n° 6214, pp. 1162-1163, DOI:10.1126/science.346.6214.1162

- ↑ Shocking satellite images show illicit archeological excavation in Syria

- ↑ Balty, 1988, p. 91.

- 1 2 Foss, 1997, p. 207.

- ↑ Foss, 1997, p. 209.

- ↑ Crawford; Goodway, 1990, p. 119.

- ↑ Foss, 1997, p. 208.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 146–149, 150.

- ↑ Finlayson, 2012, p. 308.

- ↑ Finlayson, 2012, p. 309.

- ↑ Finlayson, 2012, p. 310.

- ↑ Finlayson, 2012, p. 292.

- 1 2 Finlayson, 2012, p. 278.

- ↑ Finlayson, 2012, p. 285.

- ↑ Finlayson, Cynthia (31 May 2012). "Uncovering the Great Theater of Apamea". Popular Archaeology. Retrieved 6 November 2012.

- ↑ Echos d'Orient 1907, p. 94.

- ↑ Jean Richard, "Note sur l'archidiocèse d'Apamée et les conquêtes de Raymond de Saint-Gilles en Syrie du Nord", in Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire, Year 1946, Volume 25, n° 1, pp. 103–108

- ↑ Konrad Eubel, Hierarchia Catholica Medii Aevi, vol. 1, p. 94; vol. 2, pp. XIV and 90

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 834

- ↑ Sāmī Nasīb Makārim (1974). The Druze faith. Caravan Books. ISBN 978-0-88206-003-3. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- ↑ Wahbah A. Sayegh (1996). The Tawhid Faith: Pioneers and their shrines. The Society. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

Sources and external links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Apamea. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Apamea. |

- GCatholic Latin titular see with incumbent biography links

- GCatholic Melkite titular Metropolitan see with incumbent biography links

- GCatholic Syrian Catholic titular Metropolitan see with incumbent biography links

- GCatholic Maronite titular episcopal see with incumbent biography links

- Suggestion to have Apamea recognized as a UNESCO world heritage site (in French)

- Images by Michał Jacykiewicz

Bibliography

- William Smith (editor); Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, "Apameia", London, (1854)

- R. F. Burton and T. Drake, Unexplored Syria

- E. Sachau, Reise in Syrien, 1883.