Pickaninny

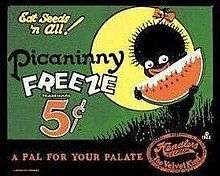

Pickaninny (also picaninny, piccaninny or pickinniny) is, in North American usage, a racial slur which refers to a depiction of a dark-skinned child of African descent. It is a pidgin word form, which may be derived from the Portuguese pequenino[1] (a diminutive version of the word pequeno, "little"). In modern sensibility, the term implies a caricature which can be used in a derogatory and racist sense.[2] According to the scholar Robin Bernstein, who describes the meaning in the context of the United States, the pickaninny is characterized by three qualities: "the figure is always juvenile, always of color, and always resistant if not immune to pain".[3]

Usage

Although the Oxford English Dictionary quotes an example from 1653 of the word "pickaninny" used to describe a child,[4] it may also have been used in early African American vernacular to indicate anything small, not necessarily a child. In a column in The Times of 1788, allegedly reporting a legal case in Philadelphia, a slave is charged with dishonestly handling goods he knows to be stolen and which he describes as insignificant, "only a piccaninny cork-screw and piccaninny knife — one cost six-pence and tudda a shilling..." The anecdote goes on to make an anti-slavery moral however, when the black person challenges the whites for dishonestly handling stolen goods too - namely slaves - so it is perhaps more likely to be an invention than factual. The deliberate use of the word in this context however suggests it already had black vernacular associations.[5] In 1826 an Englishman named Thomas Young was tried at the Old Bailey in London on a charge of enslaving and selling four Gabonese women known as "Nura, Piccaninni, Jumbo Jack and Prince Quarben".[6]

In the Southern United States, pickaninny was long used to refer to the children of African slaves or (later) of dark-skinned African American citizens. While this use of the term was popularized in reference to the character of Topsy in the 1852 book Uncle Tom's Cabin, the term was used as early as 1831 in an anti-slavery tract "The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave, related by herself" published in Edinburgh, Scotland. The term was still in some use in the United States as late as the 1960s.

The term piccaninny was used in colonial Australia for an Aboriginal child and is still in use in some Indigenous Kriol languages.[7][8]

In the Patois dialect of Jamaica, the word has been shortened to the form "pickney", which is used to describe a child regardless of racial origin.

In the Pidgin English dialects of Ghana, Nigeria and Cameroon, "pikin" is used to describe a child.

The word "pikinini" is used in Tok Pisin, Solomon Pijin and Bislama (the Melanesian pidgin dialects of Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands and Vanuatu respectively) the word for 'child' or 'children'. Unlike the situation in the U.S., there are no racist overtones to the word in these languages.

The word piccaninny (sometimes spelled "picanninnie") was also used in Australia during the 19th and 20th centuries. Its use is reflected in historic newspaper articles and numerous place names. Examples of the latter include Piccaninnie Ponds near Port Macdonnell, Piccaninny Lake in Renmark, Piccaninny crater and Picaninny Creek in Western Australia and Picaninny Point in Tasmania.[9]

Examples

In literature, films, and music

Many old lullabies have the word "pickaninny" in them — used as an affectionate term for babies — often interchangeable with a child's name, i.e.: to personalize the song many families have substituted the children's name. "It's time for little Pickaninnies to go to sleep."

Samuel Foote's 1755 nonsense prose includes: "there were present the Picninnies, and the Joblillies, and the Garyulies, and the grand Panjandrum himself...."

In the 1931 film The Front Page, one of the reporters played by Frank McHugh calls in a story to his newspaper about a colored woman giving birth to a pickaninny in the back of a cab. The term is used twice in the scene.

The word "pickaninnies" appears in the 1887 lyrics of Newfoundland folk song Kelligrew's Soiree: "There was boiled guineas, cold guineas, bullock's heads and piccaninnies."

Scott Joplin wrote the music for a lyric by Henry Jackson called "I Am Thinking of My Pickanniny Days," written in 1902.

In the novel Peter Pan by J. M. Barrie, the Indians of Neverland are members of the Piccaninny tribe.

The original version of the 1914 lullaby "Hush-A-Bye, Ma Baby" ("The Missouri Waltz") contains the line "when I was a Pickaninny on ma Mammy's knee." When it became the state song of Missouri in 1949, the word "pickaninny" was replaced with "little child." [10]

The term is used in the fourth verse of the Jimmie Rodgers tune "Peach Pickin' Time in Georgia", "When the picannies pick the cotton, I'll pick a wedding ring."

In Flannery O'Connor's "A Good Man Is Hard to Find", the grandmother uses the term: "'In my time,' said the grandmother, folding her thin veined fingers, 'children were more respectful of their native states and their parents and everything else. People did right then. Oh, look at the little pickaninny!' she said and pointed to a negro child standing in the door of a shack. 'Wouldn't that make a picture.'"

In the 1920s F. Scott Fitzgerald used the word "pickaninnies" to describe young black children playing in the street, in his short story "The Ice Palace".

Throughout his 1935 travel book Journey Without Maps, British author Graham Greene uses "piccaninny" as a general term for African children. In Margaret Mitchell's best-selling 1936 epic Gone with the Wind, Melanie Wilkes objects to her husband's intended move to New York City because it would mean that their son Beau would be educated alongside Yankees and pickaninnies.[11] Orson Scott Card's historical fantasy series The Tales of Alvin Maker uses the term, such as in Seventh Son: "Papooses learnt to hunt, pickaninnies learnt to tote...."

Also in 1935 the Shirley Temple film The Little Colonel features the grandfather Colonel barking "piccaninny" at two young children.

In the 1935 Shirley Temple film The Littlest Rebel the word "pickaninny" is used to describe the young slave children who are friends to Virgie, but excluded from her birthday party at the beginning of the film.

In the 1936 film Poor Little Rich Girl, Shirley Temple sings the song "Oh, My Goodness" to four ethnically stereotyped dolls. The fourth doll, representing a black African woman or girl, is addressed as "pickaninny".

In the 1936 Hal Roach feature General Spanky starring the Our Gang children, Buckwheat gets his foot tangled in the cord that blows the whistle on the river boat. Buckwheat is untangled by the captain of the river boat who hands him over to his master and tells him to "keep an eye on that little pickaninny."

Early editions of the longest-running British children's comic book, "The Beano", launched in 1938, featured a pickaninny character, Little Peanut, on its masthead.

In the 1940 film Philadelphia Story, photographer Liz Imbrie (Ruth Hussey) uses the term while inspecting the house of Tracy Lord (Katharine Hepburn).

In the 1940 film His Girl Friday, McCue, one of the press room reporters, jokes that "Mrs. Phoebe DeWolfe" gave birth to a pickaninny in a patrol wagon, concluding, "When the pickaninny was born, the Rifle Squad examined him carefully to see if it was Earl Williams. Well, they knew he was hiding somewhere." In the movie, Earl Williams is an escaped death row convict.

Marjorie Reynolds dresses as a stereotypical pickaninny figure in the 1942 film Holiday Inn.

In the opening line of Robert Wise's 1959 film Odds Against Tomorrow which tackled issues of racism, Robert Ryan's character picks up a young black girl after she bumps into him and says, "You little pickaninny, you're gonna kill yourself flying like that."

The 1968 Country Joe and the Fish album Together includes the fiercely ironic "Harlem Song", with the lyric "Every little picaninny wears a great big grin".

The Australian folk-rock band Redgum used the word in their song "Carrington Cabaret" dealing with white indifference to the problems of aboriginal Australia on their 1978 album If You Don't Fight You Lose.

In Stephen King's It, one of Richard Tozier's Voices is a black man named Pickaninny Jim, who refers to the character Beverly Marsh as "Miss Scawlett" in a reference to Gone with the Wind.

In the 1987 movie Burglar, Ray Kirschman (played by G.W. Bailey) confronts ex-con Bernice Rhodenbarr (Whoopi Goldberg) in her bookstore by saying "now listen here, pickaninny!"

The word was used by Australian country music performer Slim Dusty in the lyrics of his 1987 "nursery-rhyme-style" song "Boomerang": "Every picaninny knows, that's where the roly-poly goes."

Pickaninny was used in the 1995 Mario Van Peebles film Panther in a denigrating fashion by Oakland police officer characters to describe an African American child who was killed in a car accident.

In Spike Lee's 2000 film Bamboozled, the representation of African-Americans in popular media is examined and pickaninny representations figure prominently in the film.

._Port_Moresby%2C_Papua_New_Guinea._(10682223463).jpg)

In the second season of Luke Cage on Netflix, the Jamaica-raised character Bushmaster uses the term "pickney" on multiple occasions as a patois term for children, either children in general or to mean the adult child of someone. [12]

Controversial usage

The term was controversially used ("wide-grinning picaninnies") by the British Conservative politician Enoch Powell when he quoted a letter in his "Rivers of Blood" speech on 20 April 1968. In 1987, Governor Evan Mecham of Arizona defended the use of the word, claiming: "As I was a boy growing up, blacks themselves referred to their children as pickaninnies. That was never intended to be an ethnic slur to anybody."[13] Before becoming the Mayor of London, Boris Johnson wrote that "the Queen has come to love the Commonwealth, partly because it supplies her with regular cheering crowds of flag-waving piccaninnies." He later apologised for the article.[14][15]

Chess term

The term is in current use as a technical term in Chess Problems, for a particular set of moves by a black pawn. See: Pickaninny (chess).

Related terms

Cognates of the term appear in other languages and cultures, presumably also derived from the Portuguese word, and it is not controversial or derogatory in these contexts. It is in widespread use in Melanesian pidgin and creole languages such as Tok Pisin of Papua New Guinea, as the word for "child" (or just young, as in the phrase pikinini pik, meaning piglet). Indeed, even in quite formal events, HRH Prince Charles is referred to using the term in Tok Pisin, and has delighted in describing himself, when using this language in speeches to native speakers, as, "nambawan pikinini blong Kwin" ("number-one pickaninny belong queen", i.e. The First Child of the Queen).[16]

In certain dialects of Caribbean English, the words pickney and pickney-negger are used to refer to children. Also, in Nigerian as well as Cameroonian Pidgin English, the word pikin is used to mean a child.[17] And in Sierra Leone Krio[18] the term pikin refers to child or children, while in Liberian English the term pekin does likewise. In Chilapalapa, a pidgin language used in Southern Africa, the term used is pikanin. In Sranan Tongo and Ndyuka of Suriname the term pikin may refer to children as well as to small or little. Some of these words may be more directly related to the Portuguese pequeno than to pequenino, the source of pickaninny.

See also

References

- ↑ "pickaninny". Oxford English Dictionary online (draft revision ed.). March 2010.

Probably < a form in an (sic) Portuguese-based pidgin < Portuguese pequenino boy, child, use as noun of pequenino very small, tiny (14th cent.; earlier as pequeninno (13th cent.))...

- ↑ Room, Adrian (1986). A dictionary of true etymologies. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul Inc. p. 130.

- ↑ Bernstein, Robin (2011). Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights. New York: New York University Press. p. 35.

- ↑ "pickaninny". Oxford English Dictionary online (draft revision ed.). March 2009.

1653 in N. & Q. (1905) 4th Ser. 10 129/1 Some women [in Barbados], whose pickaninnies are three yeares old, will, as they worke at weeding..suffer the hee Pickaninnie, to sit astride upon their backs.

- ↑ "Black and White, A Modern Anecdote", The Times, 22 August 1788; Issue 1148; p.4; col B.

- ↑ The Times, 25 October 1826; Issue 13100; p.3; col A, Admiralty Sessions, Old Bailey, Oct. 24.

- ↑ "National Museum of Australia - 'Last of the Tribe'". nma.gov.au.

- ↑ Meakens, Felicity (2014). Language contact varieties. p. 367. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Maiden, Siobhan. "The Picaninny Point Debacle". ABC Australia. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ http://www.sos.mo.gov/archives/history/song

- ↑ http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0200161.txt

- ↑ https://www.netflix.com/title/80002537

- ↑ Watkins, Ronald J. (1990). High Crimes and Misdemeanors: The Term and Trials of Former Governor Evan Mecham. William Morrow & Co. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-688-09051-7.

- ↑ "Boris says sorry over 'blacks have lower IQs' article in the Spectator". Evening Standard. 2 April 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ↑ Telegraph: Original article by Boris Johnson from 10 January 2002

- ↑ "Prince of Wales, 'nambawan pikinini', visits Papua New Guinea" in The Telegraph, 4 Nov 2012

- ↑ Faraclas, Nicholas G. Nigerian Pidgin. p. 45. N.p.: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0-415-02291-6, p. 45, via Google Books.

- ↑ Cassidy, Frederic Gomes and Robert Brock Le Page. Dictionary of Jamaican English. p. 502. 2nd Edition. Barbados, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 2002. ISBN 976-640-127-6. via Google Books

External links

| Look up pickaninny in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pickaninny. |

- An article on the Pickaninny caricature