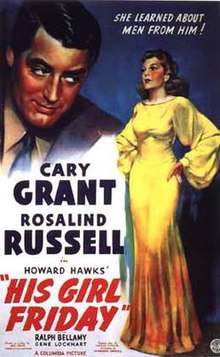

His Girl Friday

| His Girl Friday | |

|---|---|

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Howard Hawks |

| Produced by | Howard Hawks |

| Screenplay by | Charles Lederer |

| Based on |

The Front Page 1928 play by Ben Hecht Charles MacArthur |

| Starring |

Cary Grant Rosalind Russell Ralph Bellamy Gene Lockhart |

| Music by |

Sidney Cutner Felix Mills |

| Cinematography | Joseph Walker |

| Edited by | Gene Havlick |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

His Girl Friday is a 1940 American screwball comedy film directed by Howard Hawks, starring Rosalind Russell and Cary Grant, and released by Columbia Pictures. The plot centers on a newspaper editor named Walter Burns who is about to lose his newly engaged ace reporter ex-wife Hildy Johnson to another man. Burns suggests they cover one more story together, getting themselves entangled in the case of murderer Earl Williams as Burns desperately tries to win back his wife. The screenplay was adapted from the play The Front Page by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. This was the second time the play had been adapted for the screen, the first occasion being the 1931 film also called The Front Page.[1]

The script was written by Charles Lederer, Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur. The major change in this version, introduced by Hawks, is that the role of Hildy Johnson is a woman. Filming began in September 1939 and finished in November 1939, seven days past schedule. Production was delayed because the frequent improvisation and numerous ensemble scenes required many retakes. Hawks encouraged his actors to be aggressive and spontaneous, creating several moments in which the characters break the fourth wall.

In December 2017, Montreal Canada based independent theatre company, Snowglobe Theatre's Artistic Director Peter Giser adapted the script for the stage, expanded some characters and made the play more accessible to modern audiences. It was performed that December after Snowglobe obtained copyright status of this adapted version.

The film has been noted for its surprises, comedy and rapid, overlapping dialogue. Hawks himself was determined to break the record for the fastest film dialogue, at the time held by The Front Page. He used a sound mixer on the set to increase the speed of dialogue; he held a showing of the two films next to each other to prove how fast his film was.

The film was #19 on American Film Institute's 100 Years...100 Laughs and was selected in 1993 for preservation in the United States National Film Registry of the Library of Congress as "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot

Walter Burns (Cary Grant) is a hard-boiled editor for The Morning Post who learns his ex-wife and former star reporter, Hildegard "Hildy" Johnson (Rosalind Russell), is about to marry bland insurance man Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy) and settle down to a quiet life as a wife and mother in Albany, New York. Walter determines to sabotage these plans, enticing the reluctant Hildy to cover one last story, the upcoming execution of Earl Williams (John Qualen) a shy bookkeeper convicted of murdering an African-American policeman. Walter insists Hildy and her fiancé Bruce join him for lunch. At the restaurant, Hildy insists that she and Bruce will be leaving in two hours to take a night train to Albany to be married the following day. Walter attempts to convince Bruce that Hildy is the only one who can write a story to save wrongly convicted Earl Williams. After several attempts through deceit and lies to convince Hildy to stay, Hildy eventually agrees on the condition that Walter buys a $100,000 life insurance policy from Bruce in order to receive the $1,000 commission. In the meantime, Hildy bribes the jail warden to let her interview Earl Williams in jail. Williams explains that he shot the police officer on accident. Hildy uses economic theory to explain the murder of the cop to Williams, insisting that he shot the gun because of production for use.

Walter does everything he can to keep Hildy from leaving, first setting up and accusing Bruce of stealing a watch, forcing Hildy to bail him out of jail. Exasperated, Hildy announces her retirement from her profession; however, when Williams escapes from the bumbling sheriff (Gene Lockhart) and practically falls into Hildy's lap, the lure of a big scoop proves too much for her. Walter frames Bruce again, and he is immediately sent back to jail. At this point, she realizes that Walter is behind the shenanigans, yet is powerless to bail him out again. Williams comes to the press room holding a gun to Hildy and accidentally shoots a pigeon in fear. Hildy takes the gun from him. Bruce calls, and she tells him to wait, because she has Earl Williams in the press room. Williams's friend Mollie comes looking for him, assuring him that she knows he is innocent. When reporters knock at the door, she hides Williams in a roll-top desk. At this time, the building is surrounded by other reporters and cops looking for Williams. Hildy's stern mother-in-law-to-be (Alma Kruger) enters berating Hildy for the way she is treating Bruce. Upon being harassed for Williams's whereabouts by the reporters, Mollie jumps out of the window, but isn't killed. Annoyed, Walter has his colleague "Diamond Louie" (Abner Biberman) remove Mrs. Baldwin from the room "temporarily". Hildy wants to try to get Bruce out of jail, but Walter convinces her that she should focus on her breakthrough story.

Bruce comes into the press room having wired Albany for his bail asking about the whereabouts of his mother, as Hildy is frantically typing out her story. She is so consumed with writing the story that she hardly notices as Bruce realizes his cause is hopeless and leaves to return to Albany on the 9 o'clock train. "Diamond Louie" enters the room with torn clothes, revealing that he had hit a police car while driving away with Mrs. Baldwin. Louie reveals that he wasn't sure whether or not she was killed in the accident. The crooked mayor (Clarence Kolb) and sheriff need the publicity from the execution to keep their jobs in an upcoming election, so when a messenger (Billy Gilbert) brings them a reprieve from the governor, they try to bribe the man to go away and return later, when it will be too late. Walter and Hildy find out in time to save Williams from the gallows and they use the information to blackmail the mayor and sheriff into dropping Walter's arrest for kidnapping Mrs. Baldwin. Hildy receives one last call from Bruce, again in jail because of having counterfeit money that was unknowingly transferred to him by Hildy from Walter. Hildy breaks down and admits to Walter that she was afraid that Walter was going to let her marry Bruce without a fight. Walter and Hildy send money to bail Bruce out of jail.

Afterward, Walter tells Hildy they're going to remarry, and promises to take her on the honeymoon they never had in Niagara Falls. But then Walter learns that there is a newsworthy strike in Albany, which is on the way to Niagara Falls by train. Walter leads Hildy out of the press room, asking her to carry her own suitcase.

Cast

- Cary Grant as Walter Burns

- Rosalind Russell as Hildy Johnson

- Ralph Bellamy as Bruce Baldwin

- Gene Lockhart as Sheriff Hartwell

- Porter Hall as Murphy

- Ernest Truex as Bensinger

- Cliff Edwards as Endicott

- Clarence Kolb as the Mayor

- Roscoe Karns as McCue

- Frank Jenks as Wilson

- Regis Toomey as Sanders

- Abner Biberman as Louie

- Frank Orth as Duffy

- John Qualen as Earl Williams

- Helen Mack as Mollie Malloy

- Alma Kruger as Mrs. Baldwin

- Billy Gilbert as Joe Pettibone

- Pat West as Warden Cooley

- Edwin Maxwell as Dr. Eggelhoffer

- Marion Martin as Evangeline (uncredited)

Production

Development and writing

While producing Only Angels Have Wings (1939), Howard Hawks tried to pitch a remake of The Front Page to Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures. Cary Grant was almost immediately cast in the film, but Cohn initially intended Grant to play the reporter, with radio commentator Walter Winchell as the editor.[2] Hawks's production that became His Girl Friday was originally intended to be a straightforward adaptation of The Front Page, with both the editor and reporter being male.[lower-alpha 1] But during auditions, a woman, Howard Hawks' secretary, read reporter Hildy Johnson's lines. Hawks liked the way the dialogue sounded coming from a woman, resulting in the script being rewritten to make Hildy female and the ex-wife of editor Walter Burns played by Cary Grant.[4] Cohn purchased the rights for The Front Page in January 1939.[5]

Although Hawks considered the dialogue of The Front Page to be "the finest modern dialogue that had been written", more than half of it was replaced with what Hawks believed to be better dialogue.[6] Some of the original dialogue and all of the characters' names were left the same, with the exception of Hildy's fiancé, Bruce Baldwin. Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures approved Hawks' idea for the film project. Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur who had written the original play were unavailable for screenwriting. Consequently, Hawks considered Gene Fowler as the screenwriter, but declined the job because he disliked the changes to the screenplay Hawks intended to make.[5] Hawks instead recruited Charles Lederer who had worked on the adaptation for The Front Page to work on the screenplay.[7] Though he was not credited, Hecht did assist Lederer in the adaptation.[8] Additions were made in the beginning of the screenplay by Lederer to give the characters a convincing backstory so it was decided that Hildy and Walter would be divorced with Hildy's intentions of remarriage serving as Walter's motivation to win her back.[9]

During writing, Hawks was in Palm Springs directing Only Angels Have Wings, yet stayed in close contact with Lederer and Hecht during writing.[5] Hecht helped Lederer with some organizational revisions and Lederer finished the script on May 22. After two more drafts completed by July, Hawks called Morrie Ryskind to revise the dialogue and make it more interesting. Ryskind revised the script throughout the summer and finished by the end of September, before filming began. More than half of the original dialogue was rewritten.[5] The film lacks one of the well-known final lines of the play, "the son-of-a-bitch stole my watch!", because films of the time were more censored than Pre-code Hollywood films and Hawks felt that the line was too overused. Ryskind developed a new ending in which Walter and Hildy start fighting immediately after saying "I do" in the wedding they hold in the newsroom with one of the characters stating, "I think it's gonnna turn out all right this time." However, after revealing the ending to a few writer's at Columbia one evening, Ryskind was surprised to hear that his ending was filmed on another set a few days later.[10]

Forced to create another ending, Ryskind ended up thanking the anonymous Columbia writer, because he felt that his ending and ones of his final lines, "I wonder if Bruce can put us up," were better than what he had written originally.[10] After reviewing the screenplay, the Hays Office saw no issues with the film, besides a few derogatory comments towards newsmen and some illegal behavior of the characters. During some rewrites for censors, Hawks focused on finding a lead actress for his film.[11]

Ad-libs by Grant

Grant's character describes Bellamy's character by saying "He looks like that fellow in the movies, you know...Ralph Bellamy!" According to Bellamy, the remark was ad libbed by Grant.[12] Columbia studio head Harry Cohn thought it was too cheeky and ordered it removed, but Hawks insisted that it stay. Grant makes several other "inside" remarks in the film. When his character is arrested for a kidnapping, he describes the horrendous fate suffered by the last person who crossed him: Archie Leach (Grant's birth name).[13] Another line that people think is an inside remark is when Earl Williams attempts to get out of the rolltop desk he's been hiding in, Grant says, "Get back in there, you Mock Turtle." The line is a "cleaned-up" version of a line from the stage version of The Front Page ("Get back in there, you God damned turtle!") and Grant also played "The Mock Turtle" in the 1933 film version of Alice in Wonderland.[14]

Casting

Hawks had great difficulty casting this film. While the choice of Cary Grant was almost instantaneous, the casting of Hildy was a more extended process. At first, Hawks wanted Carole Lombard, whom he had directed in the screwball comedy Twentieth Century, but the cost of hiring Lombard in her new status as a freelancer proved to be far too expensive, and Columbia could not afford her. Katharine Hepburn, Claudette Colbert, Margaret Sullivan, Ginger Rogers and Irene Dunne were offered the role, but turned it down, Dunne because she felt the part was too small and needed to be expanded. Jean Arthur was offered the part, and was suspended by the studio when she refused to take it. Joan Crawford was reportedly also considered.[12] Hawks then turned to Rosalind Russell who had just finished MGM's The Women (1939).[15]

Russell was upset when she discovered from a New York Times article that Cohn was "stuck" with her after attempting to cast many other actresses. Before Russell's first meeting with Hawks, she took a swim and entered his office with wet hair, causing him to do a "triple take". Russell confronted him about this casting issue; he dismissed her quickly and asked her to go to wardrobe.[15] During filming, Russell noticed that Hawks treated her like an also-ran, so she confronted him: "You don't want me, do you? Well, you're stuck with me, so you might as well make the most of it."[16]

Filming

After makeup, wardrobe, and photography tests, filming began on September 27. The film had the working title of The Bigger They Are.[14] In her autobiography, Life Is A Banquet, Russell wrote that she thought her role did not have as many good lines as Grant's, so she hired her own writer to "punch up" her dialogue. With Hawks encouraging ad-libbing on the set, Russell was able to slip her personal, paid writer's work into the movie. Only Grant was wise to this tactic and greeted her each morning saying, "What have you got today?"[17] Her ghostwriter gave her some of the lines for the restaurant scene, which is unique to His Girl Friday. It was one of the most complicated scenes to film, because of the rapidity of the dialogue, none of the actors actually eat during the scene despite the fact that there is food in the scene. Hawks shot this scene with one camera a week and a half into production and it took four days to film instead of the intended two.[18] The film was shot with some improvisation of lines and actions, with Hawks giving the actors freedom to experiment as he did with his comedies more than his dramas.[19] The film is noted for its rapid-fire repartee, using overlapping dialogue to make conversations sound more realistic, with one character speaking before another finishes. Although overlapping dialog is specified and cued in the 1928 play script by Hecht and MacArthur,[20] Hawks told Peter Bogdanovich:

I had noticed that when people talk, they talk over one another, especially people who talk fast or who are arguing or describing something. So we wrote the dialogue in a way that made the beginnings and ends of sentences unnecessary; they were there for overlapping.[16]

To get the effect he wanted, as multi-track sound recording was not yet available at the time, Hawks had the sound mixer on the set turn the various overhead microphones on and off as required for the scene, as many as 35 times.[14] Reportedly, the film was sped up because of a challenge Hawks took upon himself to break the record for the fastest dialogue on screen, at the time held by The Front Page.[19] Hawks arranged a showing for newsmen of the two films next to each other to prove how fast his dialogue was.[21] Filming was difficult for the cinematographers because the improvisation made it difficult to know what the characters were going to do. Rosalind Russell was also difficult to film because of her lack of a sharp jawline, requiring makeup artists to paint and blend a dark line under her jawline while shining a light on her face to simulate a more youthful appearance.[21]

Hawks encouraged aggressiveness and unexpectedness in the acting, a few times breaking the fourth wall in the film. At one point, Grant broke character because of something unscripted that Russell did and looked directly at the camera saying, "Is she going to do that?". Hawks decided to leave this scene in the picture.[21] Due to the numerous amount of ensemble scenes, many retakes were necessary. Having learned from Bringing Up Baby (1938), Hawks added some straight supporting characters in order to balance out the leading characters.[18] Arthur Rosson worked for three days on second unit footage at Columbia Ranch. Filming was completed on November 21, seven days past schedule. Unusual for the time period, the film contains no music besides the music that leads to the final fade out of the film.[22]

Analysis

The title His Girl Friday is an ironical title, because a girl "Friday" represents a servant of a master, but Hildy is not a servant in the film, but rather the equal to Walter, her male counterpart. The world in this film is not determined by gender, but rather by intelligence and culpability. At the beginning of the film Hildy says that she wants to be "treated like a woman", but her return to her profession reveals her true desire to live a freer life.[23]

Themes

Criticism of domesticity

In His Girl Friday, even though the characters remarry, Hawks displays an aversion to marriage, home, and family through his approach to the film. Specific, exclusionary camera work and character control of the frame and the dialogue portray a subtle criticism of domesticity. [24]The subject of domesticity is fairly absent throughout the film. Even among the relationships between Grant and Russell and Bellamy and Russell, the relationships are positioned within a larger frame of the male predominated newsroom.[24]

Symbols and motifs

Hawks is known for his use of repeated or intentional gestures in his films. In His Girl Friday, the cigarette in the scene between Hildy and Earl Williams serves several symbolic roles in the film. First, the cigarette establishes a link between the characters when Williams accepts the cigarette even though he does not smoke. However, the fact that he doesn't smoke and they don't share the cigarette shows the difference between and separation of the worlds in which the two characters live.[25]

Style

The film contains two main plots: the romantic and the professional. Walter and Hildy work together to attempt to release wrongly convicted Earl Williams, while the concurrent plot is Walter attempting to win back Hildy. The two plots do not resolve at the same time, but they are interdependent because although Williams is released before Walter and Hildy get back together, he is the reason for their reconciliation.[26]

The speed of the film is particularly notable and is characterized by snappy and overlapping dialogue among interruptions and rapid speech. Gesture, character and camera movement, as well as editing, serve to complement the dialogue in increasing the pace of the film. There is a clear contrast between the fast-talking Hildy and Walter and slow-talking Bruce and Earl which serves to emphasize the gap between the intelligent and the unintelligent in the film. The average word per minute count of the film is 240 while average American speech is around 140 words per minute. There are nine scenes with at least four words per second and at least two with more than five words per second.[27] Hawks attached verbal tags before and after specific script lines so the actors would be able to interrupt and talk over each other without making the necessary dialogue incomprehensible.[28]

Closure Effect

A commonality in many Howard Hawks films in the revelation of the amorality of the main character and an inability of the protagonist to change or develop as a character. In His Girl Friday, Walter Burns manipulates, acts based on his own gain, frames his ex-wife's fiancé, and orchestrates the kidnapping of an elderly woman. Even at the end of the film, Burns convinces Hildy Johnson to remarry him despite how much she loathes him and his questionable actions. Upon the reconciliation of their relationship, there is no romance visible between each other. They do not kiss, embrace, or even gaze at each other. It is evident that Burns is still the same person as he was in their previous relationship as he quickly waves off the plans for the honeymoon that they never had in pursuit of a new story. Additionally, he walks in front of her when exiting the room, forcing her to carry her own suitcase, despite Johnson having already criticized that as being ungentleman-like in the beginning of the film. It's clear that the marriage is fated to face the same problems that ended it before.[29]

Film theorist and historian David Bordwell explained the ending of His Girl Friday as a "closure effect" rather than a closure. The ending of the film is rather circular and there is no development of characters, specifically Walter Burns, and the film ends similar to the way in which is starts. Additionally, the film ends with a brief epilogue in which the Watler announces their remarriage and reveals their intention to go cover a strike in Albany on the way to their honeymoon and they consider staying with Bruce in Albany. The fates of the main characters and even some of the minor characters such as Earl William are revealed, except there are minor flaws in the resolution. For example, they do not discuss what happens to Molly Malloy after the conflict resolved. However, the main characters endings were wrapped up so well that it overshadows the need for the minor characters' endings to be wrapped up. This creates a "closure effect" or an appearance of closure.[30]

Release

Release of the film was rushed by Cohn and a sneak preview of the film was held in December, with a press screening on January 3, 1940.[22] His Girl Friday premiered in New York City at Radio City Music Hall on January 11, 1940, and went into general American release a week later.[31][32]

Reception

Contemporary reviews from critics were very positive. Critics were particularly impressed by the gender change of the reporter.[22] Frank S. Nugent of The New York Times wrote, "Except to add that we've seen 'The Front Page' under its own name and others so often before we've grown a little tired of it, we don't mind conceding 'His Girl Friday' is a bold-faced reprint of what was once—and still remains—the maddest newspaper comedy of our times."[1] Variety wrote, "The trappings are different—even to the extent of making reporter Hildy Johnson a femme—but it is still 'Front Page' and Columbia need not regret it. Charles Leder (sic) has done an excellent screenwriting job on it and producer director Howard Hawks has made a film that can stand alone almost anywhere and grab healthy grosses."[33] Harrison's Reports wrote, "Even though the story and its development will be familiar to those who saw the first version of 'The Front Page,' they will be entertained just the same, for the action is so exciting that it holds one in tense suspense throughout."[34] Film Daily wrote, "Given a snappy pace, a top flight cast, good production and able direction, film has all the necessary qualities for first-rate entertainment for any type of audience."[35] John Mosher of The New Yorker wrote that after years of "feeble, wispy, sad imitations" of The Front Page, he found this authentic adaptation of the original to be "as fresh and undated and bright a film as you could want."[36] Louis Marcorelles called His Girl Friday, "le film américain par excellence".[37]

Legacy

His Girl Friday (often along with Bringing up Baby and Twentieth Century) is cited as an archetype of the screwball comedy genre.[38] In 1993, the Library of Congress selected His Girl Friday for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.[39] The film also ranked 19th on the American Film Institute's 100 Years...100 Laughs, a 2000 list of the funniest American comedies.[40] Prior to His Girl Friday the play The Front Page had been adapted for the screen once before, in the 1931 Howard Hughes-produced film also called The Front Page with Adolphe Menjou and Pat O'Brien in the starring roles.[41] In this first film adaptation of the Broadway play of the same title (written by former Chicago newsmen Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur), Hildy Johnson was male.[1]

His Girl Friday was dramatized as a one-hour radio play on the September 30, 1940 broadcast of Lux Radio Theater with Claudette Colbert, Fred MacMurray and Jack Carson.[42] It was dramatized again with a half-hour version on The Screen Guild Theater on March 30, 1941 with Grant and Russell reprising their film roles.[43][44] "The Front Page" was remade in a 1974 Billy Wilder movie starring Walter Mattheau, Jack Lemmon, and Susan Sarandon. Walter Mattheau as Walter Burns, with Jack Lemmon as Hildy Johnson and Susan Sarandon as his fiance.[45][46]

His Girl Friday and the original Hecht and MacArthur play were later adapted into another stage play, His Girl Friday, by playwright John Guare. This was presented at the National Theatre, London, from May to November 2003, with Alex Jennings as Burns and Zoë Wanamaker as Hildy.[47][48] The 1988 film Switching Channels was loosely based on His Girl Friday, with Burt Reynolds in the Walter Burns role, Kathleen Turner in the Hildy Johnson role, and Christopher Reeve in the role of Bruce.[49]

Quentin Tarantino, the director of Pulp Fiction (1994), has named His Girl Friday as one of his favorite movies.[50] In the 2004 film Notre musique, in Godard's classroom he explains the basic of film, specifically the shot reverse shot. As he explains this concept, two stills from His Girl Friday are shown with Cary Grant in one photo and Rosalind Russell in the other. He explains that upon looking closely, the two shots are actually the same shot, "because the director is incapable of seeing the difference between a man and a woman."[51]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 1998: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated[52]

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #19[53]

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[54]

- 2007: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated[55]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- Nominated Romantic Comedy Film[56]

References

Informational notes

- ↑ A "girl Friday" is an assistant who carries out a variety of chores. The name alludes to "Friday", Robinson Crusoe's native male dogsbody in Daniel Defoe's novel. According to Merriam-Webster's, the term was first used in 1940 (the year the film was released).[3]

Citations

- 1 2 3 Nugent, Frank S. (January 12, 1940). "Movie Review His Girl Friday (1940) THE SCREEN IN REVIEW; Frenzied's the Word for 'His Girl Friday,' a Distaff Edition of 'The Front Page,' at the Music Hall--'The Man Who Wouldn't Talk' Opens at the Palace". The New York Times.

- ↑ McCarthy 1997, p. 278.

- ↑ "Girl Friday". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ↑ Phillips 2010, p. 308.

- 1 2 3 4 McCarthy 1997, p. 279.

- ↑ Mast 1982, pp. 208-209.

- ↑ Grindon 2011, p. 96.

- ↑ Martin 1985, p. 95.

- ↑ Grindon 2011, p. 97.

- 1 2 McCarthy 1997, p. 281.

- ↑ McCarthy 1997, pp. 281-282.

- 1 2 Notes TCM

- ↑ Fetherling 1977, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Frank. "His Girl Friday".

- 1 2 McCarthy 1997, p. 282.

- 1 2 Osborne, Robert, Turner Classic Movie broadcast

- ↑ New York : Random House, 1977. ISBN 978-0-394-42134-6 OCLC 3017310

- 1 2 McCarthy 1997, p. 285.

- 1 2 McCarthy 1997, p. 283.

- ↑ Hecht, Ben, & Charles MacArthur, The Front Page, 1928. Samuel French, Inc.

- 1 2 3 McCarthy 1997, p. 284.

- 1 2 3 McCarthy 1997, p. 286.

- ↑ Grindon 2011, p. 105.

- 1 2 Danks 2016, pp. 35-38.

- ↑ Neale 2016, p. 110; McElhaney 2006, pp. 31–45

- ↑ Bordwell 1985, p. 158.

- ↑ Grindon 2011, p. 103.

- ↑ Mast 1982, p. 49.

- ↑ Dibbern 2016, p. 230.

- ↑ Bordwell 1985, p. 159; Dibbern 2016, p. 230

- ↑ Cohn, Herbert (January 12, 1940). "'His Girl Friday' Makes Gay Music Hall Comedy". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 11. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "At the Logan Wednesday". The Logan Daily News. January 22, 1940. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "His Girl Friday". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc. January 10, 1940. p. 14.

- ↑ "'His Girl Friday' with Cary Grant, Rosalind Russell and Ralph Bellamy". Harrison's Reports: 3. January 6, 1940.

- ↑ "Reviews of the New Films". Film Daily. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc.: 5 January 5, 1940.

- ↑ Mosher, John (January 13, 1940). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing Corp. p. 59.

- ↑ Bordwell 1985, p. 188.

- ↑ Brookes 2016, p. 2.

- ↑ Clamen, Stewart M. "U.S. National Film Registry — Titles". Clamen's Movie Information Collection. Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ↑ "America's Funniest Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ↑ Fristoe, Roger; Nixon, Rob. "The Front Page (1931)". Film Article. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ↑ "Spotlighting the Dial – Dramatic Programs". The Milwaukee Journal. 1940-09-30. p. 2 (Green Sheet). Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ↑ "TONIGHT - 7:30 WJAS (advertisement)". The Pittsburgh Press. 1941-03-30. p. 3 (section 5). Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ↑ "Screen Guild Theater". Internet Archive. March 26, 2007.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (December 19, 1974). "Wilder's Uneven Film of 'Front Page'". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ "Winners and Nominees: The Front Page". Golden Globes Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ Tarloff, Erik (July 6, 2003). "Theater; The Play of the Movie of the Play". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ Billington, Michael (June 6, 2003). "His Girl Friday". The Guardian. Guardian New and Media Limited. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (March 4, 1988). "Film: Turner in 'Switching Channels'". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Greatest Films Poll - 2012 - Quentin Tarantino". British Film Institute. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ↑ McElhaney 2016, p. 199.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies Nominees (10th Anniversary Edition)" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-07-17.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

Bibliography

- Bordwell, David (1985). Narration in the Fiction Film. Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299101703.

- Brookes, Ian, ed. (2016). Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. ISBN 9781844575411.

- Danks, Adrian (2016). "'Ain't There Anyone Here for Love?' Space, Place and Community in the Cinema of Howard Hawks". In Brookes, Ian. Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. pp. 35–38. ISBN 9781844575411.

- Dibbern, Doug (2016). "Irresolvable Circularity: Narrative Closure and Nihilism in Only Angels Have Wings". In Brookes, Ian. Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. 9781844575411: Palgrave. p. 230.

- Fetherling, Doug (1977). The Five Lives of Ben Hecht. Toronto: Lester and Orpen Ltd. ISBN 0919630855.

- Grindon, Leger (2011). The Hollywood romantic comedy: Conventions, history, controversies. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405182669. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- Martin, Jeffrey Brown (1985). Ben Hecht: Hollywood Screenwriter. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press. ISBN 083571571X.

- Mast, Gerald (1982). Howard Hawks, Storyteller. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195030915.

- McCarthy, Todd (1997). Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0802115985.

- McElhaney, Joe (2016). "Red Line 7000: Fatal Disharmonies". In Brookes, Ian. Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. p. 199. ISBN 9781844575411.

- McElhaney, Joe (Spring–Summer 2006). "Howard Hawks: American Gesture". Journal of Film and Video. 58 (1–2): 31–45. Retrieved 31 May 2018.

- Neale, Steve (2016). "Gestures, Movements and Actions in Rio Bravo". In Brookes, Ian. Howard Hawks: New Perspectives. London: Palgrave. p. 110. ISBN 9781844575411.

- Phillips, Gene (2010). Some Like It Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. p. 308. ISBN 9780813125701. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- Schlotterbeck, Jesse (2016). "Hawks's 'UnHawksian' Biopic: Sergeant York". Howard Hawks: New Perspective. London: Palgrave. p. 68. ISBN 9781844575411.

Further reading

- Walters, James (2008). "Making Light of the Dark: Understanding the World of His Girl Friday". Journal of Film and Video. 60 (3/4). Retrieved September 28, 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to His Girl Friday. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: His Girl Friday |

- His Girl Friday complete film on YouTube

- His Girl Friday on IMDb

- His Girl Friday at the TCM Movie Database

- His Girl Friday at AllMovie

- His Girl Friday is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- His Girl Friday at the American Film Institute Catalog

- His Girl Friday at Rotten Tomatoes