Peter O'Toole

| Peter O'Toole | |

|---|---|

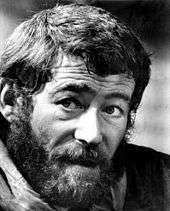

Peter O'Toole as T. E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) | |

| Born |

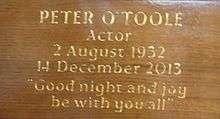

Peter James O'Toole[1] 2 August 1932 Leeds, Yorkshire, England[2] |

| Died |

14 December 2013 (aged 81) St John's Wood, London, England |

| Nationality | Disputed |

| Alma mater | Royal Academy of Dramatic Art |

| Occupation | Actor, author |

| Years active | 1954–2012 |

| Height | 6 ft 2 in (188 cm) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Partner(s) | Karen Brown (1982-1988) |

| Children | Kate O'Toole, Patricia O'Toole, and Lorcan O'Toole |

Peter James O'Toole [3] (/oʊˈtuːl/; 2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was a British stage and film actor of Irish descent. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic and with the English Stage Company before making his film debut in 1959.

He achieved international recognition playing T. E. Lawrence in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) for which he received his first nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor. He was nominated for this award another seven times – for Becket (1964), The Lion in Winter (1968), Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1969), The Ruling Class (1972), The Stunt Man (1980), My Favorite Year (1982), and Venus (2006) – and holds the record for the most Academy Award nominations for acting without a win. In 2002, O'Toole was awarded the Academy Honorary Award for his career achievements.[4] He was additionally the recipient of four Golden Globe Awards, one British Academy Film Award and one Primetime Emmy Award.

Early life

O'Toole was born in 1932. Some sources give his birthplace as Connemara, County Galway, Ireland,[5] while others cite St James University Hospital, Leeds, England.[6][7] O'Toole claimed he was not certain of his birthplace or date, noting in his autobiography that, while he accepted 2 August as his birthdate, said he had a birth certificate from each country, with the Irish one giving a June 1932 birth date. Peter had an elder sister, Patricia.[3] Records from the General Registry Office in Leeds, England confirm that Peter J (James) O'Toole was born in the north England town in 1932.[8]

He grew up in Hunslet, south Leeds, son of Constance Jane Eliot (née Ferguson), a Scottish[9] nurse, and Patrick Joseph "Spats" O'Toole, an Irish metal plater, football player and racecourse bookmaker.[10][11][12][13] When O'Toole was one year old, his family began a five-year tour of major racecourse towns in Northern England. He and his sister were brought up in the Roman Catholic faith of their father.[14][15]

O'Toole was evacuated from Leeds early in the Second World War,[16] and went to a Catholic school for seven or eight years, St Joseph's Secondary School at Joseph Street, Hunslet, where he was "implored" to become right-handed.[17] "I used to be scared stiff of the nuns: their whole denial of womanhood – the black dresses and the shaving of the hair – was so horrible, so terrifying ... Of course, that's all been stopped. They're sipping gin and tonic in the Dublin pubs now, and a couple of them flashed their pretty ankles at me just the other day", he said.[18]

Upon leaving school O'Toole obtained employment as a trainee journalist and photographer on the Yorkshire Evening Post,[19] until he was called up for national service as a signaller in the Royal Navy.[20] As reported in a radio interview in 2006 on NPR, he was asked by an officer whether he had something he had always wanted to do. His reply was that he had always wanted to try being either a poet or an actor.[21] O'Toole attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) from 1952 to 1954 on a scholarship after being rejected by the Abbey Theatre's drama school in Dublin by the director Ernest Blythe, because he couldn't speak the Irish language. At RADA, he was in the same class as Albert Finney, Alan Bates and Brian Bedford.[22] O'Toole described this as "the most remarkable class the academy ever had, though we weren't reckoned for much at the time. We were all considered dotty."[23]

Career

O'Toole began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic and with the English Stage Company, before making his television debut in 1954. He first appeared on film in 1959 in a minor role in The Day They Robbed the Bank of England.[24] O'Toole's major break came when he was chosen to play T. E. Lawrence in Sir David Lean's Lawrence of Arabia (1962), after Marlon Brando proved unavailable and Albert Finney turned down the role. His performance was ranked number one in Premiere magazine's list of the 100 Greatest Performances of All Time.[25] The role introduced him to US audiences and earned him the first of his eight nominations for the Academy Award for Best Actor. T. E. Lawrence, portrayed by O'Toole, was selected in 2003 as the tenth-greatest hero in cinema history by the American Film Institute.[26]

O'Toole was one of several actors to be Oscar-nominated for playing the same role in two different films: he played King Henry II in both Becket (1964) and The Lion in Winter (1968). O'Toole played Hamlet under Laurence Olivier's direction in the premiere production of the Royal National Theatre in 1963. He demonstrated his comedic abilities alongside Peter Sellers in the Woody Allen-scripted comedy What's New Pussycat? (1965). He appeared in Seán O'Casey's Juno and the Paycock at Dublin's Gaiety Theatre.

In 1969, he played the title role in the film Goodbye, Mr. Chips, a musical adaptation of James Hilton's novella, starring opposite Petula Clark. He was nominated for an Academy Award as Best Actor and won a Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy.

O'Toole fulfilled a lifetime ambition in 1970 when he performed on stage in Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot, alongside Donal McCann, at Dublin's Abbey Theatre. In 1972, he played both Miguel de Cervantes and his fictional creation Don Quixote in Man of La Mancha, the motion picture adaptation of the 1965 hit Broadway musical, opposite Sophia Loren. The film was a critical and commercial failure, criticised for using mostly non-singing actors. His singing was dubbed by tenor Simon Gilbert,[27] but the other actors did their own singing. O'Toole and co-star James Coco, who played both Cervantes's manservant and Sancho Panza, both received Golden Globe nominations for their performances. In 1980, O'Toole starred as Tiberius in the Penthouse-funded biopic, Caligula.

In 1980, he received critical acclaim for playing the director in the behind-the-scenes film The Stunt Man.[28][29] He received mixed reviews as John Tanner in Man and Superman and Henry Higgins in Pygmalion, and won a Laurence Olivier Award for his performance in Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell (1989).[30] O'Toole was nominated for another Oscar for My Favorite Year (1982), a light romantic comedy about the behind-the-scenes at a 1950s TV variety-comedy show, in which O'Toole plays an aging swashbuckling film star reminiscent of Errol Flynn. He also appeared in 1987's The Last Emperor, as Sir Reginald Johnston.

He won a Primetime Emmy Award for his role as Bishop Pierre Cauchon in the 1999 mini-series Joan of Arc. In 2004, he played King Priam in the summer blockbuster Troy. In 2005, he appeared on television as the older version of legendary 18th century Italian adventurer Giacomo Casanova in the BBC drama serial Casanova. The younger Casanova, seen for most of the action, was played by David Tennant, who had to wear contact lenses to match his brown eyes to O'Toole's blue. O'Toole was once again nominated for the Best Actor Academy Award for his portrayal of Maurice in the 2006 film Venus, directed by Roger Michell, his eighth such nomination.

O'Toole co-starred in the Pixar animated film Ratatouille (2007), an animated film about a rat with dreams of becoming the greatest chef in Paris, as Anton Ego, a food critic. He also appeared in the second season of Showtime's successful drama series The Tudors (2008), portraying Pope Paul III, who excommunicates King Henry VIII from the church; an act which leads to a showdown between the two men in seven of the ten episodes. Also in 2008, he starred alongside Jeremy Northam and Sam Neill in the New Zealand/British film Dean Spanley, based on an Alan Sharp adaptation of Irish author Lord Dunsany's short novel, My Talks with Dean Spanley.[31]

On 10 July 2012, O'Toole released a statement announcing his retirement from acting.[32]

Personal life

While studying at RADA in the early 1950s, O'Toole was active in protesting against British involvement in the Korean War. Later, in the 1960s, he was an active opponent of the Vietnam War. He played a role in the creation of the current form of the well-known folksong "Carrickfergus" which he related to Dominic Behan, who put it in print and made a recording in the mid-1960s.[33]

In 1959, he married Welsh actress Siân Phillips, with whom he had two daughters: actress Kate and Patricia. They were divorced in 1979. Phillips later said in two autobiographies that O'Toole had subjected her to mental cruelty, largely fuelled by drinking, and was subject to bouts of extreme jealousy when she finally left him for a younger lover.[34]

O'Toole and his girlfriend, model Karen Brown,[35] had a son, Lorcan Patrick O'Toole (born 17 March 1983), when O'Toole was fifty years old. Lorcan, now an actor, was a pupil at Harrow School, boarding at West Acre from 1996.[36]

Severe illness almost ended O'Toole's life in the late 1970s. His stomach cancer was misdiagnosed as resulting from his alcoholic excess.[37] O'Toole underwent surgery in 1976 to have his pancreas and a large portion of his stomach removed, which resulted in insulin-dependent diabetes. In 1978, he nearly died from a blood disorder.[38] He eventually recovered, however, and returned to work. He resided on the Sky Road, just outside Clifden, Connemara, County Galway from 1963, and at the height of his career maintained homes in Dublin, London and Paris (at the Ritz, which was where his character supposedly lived in the film How to Steal a Million). In an interview with National Public Radio in December 2006, O'Toole revealed that he knew all 154 of Shakespeare's sonnets. A self-described romantic, O'Toole regarded the sonnets as among the finest collection of English poems, reading them daily. In Venus, he recites Sonnet 18 ("Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?"). O'Toole wrote two memoirs. Loitering With Intent: The Child chronicles his childhood in the years leading up to World War II and was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year in 1992. His second, Loitering With Intent: The Apprentice, is about his years spent training with a cadre of friends at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

O'Toole played rugby league as a child in Leeds[39] and was also a rugby union fan, attending Five Nations matches with friends and fellow rugby fans Richard Harris, Kenneth Griffith, Peter Finch and Richard Burton. He was also a lifelong player, coach and enthusiast of cricket[40] and a fan of Sunderland A.F.C.[41]

O'Toole was interviewed at least three times by Charlie Rose on his eponymous talk show. In a 17 January 2007 interview, O'Toole stated that British actor Eric Porter had most influenced him, adding that the difference between actors of yesterday and today is that actors of his generation were trained for "theatre, theatre, theatre". He also believes that the challenge for the actor is "to use his imagination to link to his emotion" and that "good parts make good actors". However, in other venues (including the DVD commentary for Becket), O'Toole credited Donald Wolfit as being his most important mentor. In an appearance on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart (11 January 2007), O'Toole stated that the actor with whom he most enjoyed working was Katharine Hepburn.

Although he lost faith in organised religion as a teenager, O'Toole expressed positive sentiments regarding the life of Jesus Christ. In an interview for The New York Times,[42] he said "No one can take Jesus away from me... there's no doubt there was a historical figure of tremendous importance, with enormous notions. Such as peace." He called himself "a retired Christian" who prefers "an education and reading and facts" to faith.[42]

Death

O'Toole died on 14 December 2013 at Wellington Hospital in St John's Wood, London, aged 81.[43] His funeral was held at Golders Green Crematorium in London on 21 December 2013, where he was cremated in a wicker coffin.[44]

O'Toole's remains are planned to be taken to Connemara, Ireland. They are currently being kept at the residence of the President of Ireland, Áras an Uachtaráin, by the President Michael D. Higgins who is an old friend of the actor. His family plan to return to Ireland to fulfill his wishes and take them to the west of Ireland when they can.[45]

On 18 May 2014, a new prize was launched in memory of Peter O'Toole at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School; this includes an annual award given to two young actors from the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, including a professional contract at Bristol Old Vic Theatre.[46] He has a memorial plaque in St Paul's, the Actors' Church in Covent Garden.

On 21 April 2017, the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin announced that Kate O'Toole had placed her father's archive at the humanities research centre.[47] The collection includes O'Toole's scripts, extensive published and unpublished writings, props, photographs, letters, medical records, and more. It joins the archives of several of O'Toole's collaborators and friends including Donald Wolfit, Eli Wallach, Peter Glenville, Sir Tom Stoppard, and Dame Edith Evans.[48][49]

Filmography

Stage appearances

1955–58 Bristol Old Vic

- King Lear (1956) (Cornwall)

- The Recruiting Officer (1956) (Bullock)

- Major Barbara (1956) (Peter Shirley)

- Othello (1956) (Lodovico)

- The Slave of Truth (1956) (Clitandre)

- Pygmalion (1957) (Henry Higgins)

- A Midsummer Night's Dream (1957) (Lysander)

- Oh! My Papa! (1957) (Uncle Gustave)

- Look Back in Anger (1957) (Jimmy Porter)

- Man and Superman (1958) (Tanner)

- Hamlet (1958) (Hamlet)

- The Holiday (1958) (Roger)

- Amphitryon '38 (1958) (Jupiter)

- Waiting for Godot (1957) (Vladimir)

1959 Royal Court Theatre

- The Long and the Short and the Tall (Bamforth)

1960 Royal Shakespeare Company, Stratford

- The Taming of the Shrew (Petruchio)

- The Merchant of Venice (Shylock)

- Troilus and Cressida (Thersites)

1963 National Theatre

- Hamlet (title role) directed by Laurence Olivier[50]

1963–65

- Baal (Phoenix Theatre, 1963)

- Ride a Cock Horse (Piccadilly Theatre, 1965)

1966 Gaiety Theatre, Dublin

- Juno and the Paycock (Jack Boyle)

- Man and Superman (Tanner)

1969 Abbey Theatre, Dublin

- Waiting for Godot (Vladimir)

1973–74 Bristol Old Vic

- Uncle Vanya (Vanya)

- Plunder (D'Arcy Tuck)

- The Apple Cart (King Magnus)

- Judgement (monologue)

1978 Toronto, Washington and Chicago

- Uncle Vanya (Vanya)

- Present Laughter (Gary Essendine)

- Caligula (Tiberius)

1980–99

- Macbeth (1980) (Macbeth) (Old Vic Theatre)

- Man and Superman (Theatre Royal, Haymarket)

- Pygmalion (Professor Higgins) (Shaftesbury Theatre, 1984 and Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, Guildford)

- The Apple Cart (Theatre Royal Haymarket, 1986)

- Pygmalion (Professor Higgins) (Plymouth Theatre, New York, 1987)

- Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell (Apollo Theatre, 1989, Shaftesbury Theatre, 1991 and Old Vic, 1999)

- Our Song (Apollo Theatre, 1992).

Books authored

- Loitering with Intent: The Child (1992)

- Loitering with Intent: The Apprentice (1997)

Awards

Academy Award nominations

O'Toole was nominated eight times for the Academy Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, but was never able to win a competitive Oscar. In 2002,[4] the Academy honoured him with an Academy Honorary Award for his entire body of work and his lifelong contribution to film. O'Toole initially balked about accepting, and wrote the Academy a letter saying that he was "still in the game" and would like more time to "win the lovely bugger outright". The Academy informed him that they would bestow the award whether he wanted it or not. He told Charlie Rose in January 2007 that his children admonished him, saying that it was the highest honour one could receive in the filmmaking industry. O'Toole agreed to appear at the ceremony and receive his Honorary Oscar. It was presented to him by Meryl Streep, who has the most Oscar nominations of any actor or actress (19). He joked with Robert Osborne, during an interview at Turner Classic Movie's film festival that he's the "Biggest Loser of All Time", due to his lack of an Academy Award, after many nominations.[51]

References

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/otooles-claims-of-irish-roots-are-blarney-26284021.html

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/otooles-claims-of-irish-roots-are-blarney-26284021.html

- 1 2 O'Toole, Peter (1992). Loitering With Intent. London: Macmillan London Ltd. pp. 6, 10. ISBN 1-56282-823-1.

- 1 2 "The Official Academy Awards Database: Peter O'Toole". The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ↑ "Peter O'Toole biography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ Peter O'Toole: A profile of the world-famous actor from Hunslet, BBC, retrieved 17 December 2013

- ↑ Peter O'Toole: 'I will stir the smooth sands of monotony', Irish Examiner, retrieved 17 December 2013

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/irish-news/otooles-claims-of-irish-roots-are-blarney-26284021.html

- ↑ O'Toole, Peter. Loitering with Intent: Child (Large print edition), Macmillan London Ltd., London, 1992. ISBN 1-85695-051-4; pg. 10, "My mother, Constance Jane, had led a troubled and a harsh life. Orphaned early, she had been reared in Scotland and shunted between relatives;..."

- ↑ Peter O'Toole Dead: Actor Dies At Age 81, Huffington Post, retrieved 19 December 2013

- ↑ "Peter O'Toole profile at". Filmreference.com. 2008. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ↑ Frank Murphy (31 January 2007). "Peter O'Toole, A winner in waiting". The Irish World. Archived from the original on 9 May 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ↑ "Loitering with Intent Summary – Magill Book Reviews". Enotes.com. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ↑ Tweedie, Neil (24 January 2007). "Too late for an Oscar? No, no, no..." The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 11 September 2010.

- ↑ Adams, Cindy (21 March 2008). "Veteran says today's actors aren't trained". New York Post. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ↑ "Peter O'Toole: Lad from Leeds who became one of screen greats". Yorkshire Evening Post. Johnston Publishing Ltd. 15 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Mitchell, Justin (7 January 2003). "A typical American will eat 28 pigs in his lifetime - and more fascinating..." Weekly World News. 24 (17). p. 45. ISSN 0199-574X.

- ↑ Alan Waldman. "Tribute to Peter O'Toole". films42.com. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ↑ Lambourne, Helen (16 December 2013). "'You'll never make a reporter' editor told O'Toole". Hold the Fronte Page. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Suebsaeng, Asawin (15 December 2013). "How the Royal Navy Helped the Late Peter O'Toole Become an Acting Legend". Mother Jones. Foundation for National Progress. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Lee, Adrian (15 December 2013). "Remembering Peter O'Toole". The Atlantic. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ Cochrane, Claire (27 October 2011). Twentieth-Century British Theatre: Industry, Art and Empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 9781139502139.

- ↑ Guy Flatley (24 July 2007). "The Rule of O'Toole". MovieCrazed. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ↑ Glaister, Dan (29 October 2004). "After 42 years, Sharif and O'Toole decide the time is right to get their epic act together again". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ↑ "The 100 Greatest Movie Performances of All Time". Premiere magazine. April 2006.

- ↑ "Good and Evil Rival for Top Spots in AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains". American Film Institute. American Film Institute. 4 June 2003. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database: Soundtracks for Man of La Mancha 1972), imdb.com; accessed 4 November 2015.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (7 November 1980). "The Stunt Man". rogerebert.com. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (17 October 1980). "O'Toole In 'Stunt Man'". The New York Times.

- ↑ Gibbons, Fiachra. "National upsets the form book at awards". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Philip French (14 December 2008). "Dean Spanley". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ↑ "Peter O'Toole announces retirement from show biz". CBC.ca. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 10 July 2012.

- ↑ "Harris & O'Toole – Carrickfergus video". NME. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Nathan Southern (2008). "Peter O'Toole profile". Allrovi. MSN Movies. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ↑ "Model Karen Brown Somerville". December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Standing, Sarah (15 December 2013). "Remembering Peter O'Toole". GQ. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Leading Men: The 50 Most Unforgettable Actors of the Studio Era. Chronicle Books (Turner Classic Movies Film Guide). 2006. p. 165.

- ↑ Hogan, Mike (15 December 2013). "Peter O'Toole, Dead at 81, Made an Indelible Mark with Lawrence of Arabia". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ↑ "O'Toole joins the rugby league actors XIII". The Roar. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "O'Toole bowled them over in Galway". Irish Independent. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ "Peter O'Toole, a hell-raising dad and a lost Sunderland passion". Salut Sunderland. Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- 1 2 Gates, Anita (26 July 2007). "Papal Robes, and Deference, Fit O'Toole Snugly". New York Times.

- ↑ Booth, Robert (2013) "Peter O'Toole, star of Lawrence of Arabia, dies aged 81", theguardian.com, 15 December 2013; retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Peter O'Toole's ex-wife makes an appearance at his funeral The Daily and Sunday Express, 22 December 2013; retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ↑ "O'Toole's ashes heading home to Ireland". Ulster Television. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ↑ "The Peter O'Toole Prize". bristololdvic.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ "Archive Acquired of Theatre and Film Actor Peter O'Toole". utexas.edu. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ correspondent, Mark Brown Arts (21 April 2017). "Peter O'Toole personal archive heads to University of Texas". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Nyren, Erin. "Peter O'Toole Archive Acquired by University of Texas". Variety. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Ellis, Samantha (12 March 2003). "Hamlet, National Theatre, October 1963". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- ↑ "Interview de Peter O'Toole". Youtube. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter O'Toole. |

- Peter O'Toole at the Internet Broadway Database

- Peter O'Toole on IMDb

- Peter O'Toole at the TCM Movie Database

- Peter O'Toole at the BFI's Screenonline

- "Peter O'Toole as Casanova"

- University of Bristol Theatre Collection, University of Bristol

- The Making of Lawrence of Arabia, Digitised BAFTA Journal, Winter 1962–63 (with additional notes by Bryan Hewitt)

- Peter O'Toole Interview at 2002 Telluride Film Festival, conducted by Roger Ebert

- Peter O'Toole(Aveleyman)