Pakistani general election, 1970

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 300 seats in the National Assembly 151 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 63.0% | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Bangladesh |

|

|

Ancient

|

|

Classical

|

|

Medieval

|

|

Modern

|

|

Related articles |

|

|

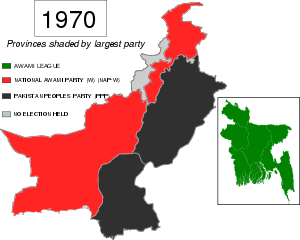

General elections were held in Pakistan on 7 December 1970. They were the first general elections held in Pakistan (East and West Pakistan) and ultimately only general elections held prior to the independence of Bangladesh. Voting took place in 300 parliamentary constituencies of Pakistan to elect members of the National Assembly of Pakistan, which was then the only chamber of a unicameral Parliament of Pakistan. The elections also saw members of the five Provincial assemblies elected in Punjab, Sindh, North West Frontier Province, Balochistan and East Pakistan.

The elections were a fierce contest between two socialist parties, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Awami League. The Awami League was the sole major party in East Pakistan, while in the four provinces of West Pakistan, the PPP faced severe competition from the conservative factions of Muslim League, the largest of which was Muslim League (Qayyum), as well as Islamist parties like Jamaat-e-Islami (JI), Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) and Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (JUP).

The Awami League won a landslide victory by winning an absolute majority of 160 seats in the National Assembly and 298 of the 310 seats in the Provincial Assembly of East Pakistan. The PPP won only 81 seats in the National Assembly, but were the winning party in Punjab and Sindh. The Marxist National Awami Party emerged victorious in Northwest Frontier Province and Balochistan

The Assembly was initially not inaugurated as President Yahya Khan and the PPP did not want a party from East Pakistan in government. This caused great unrest in East Pakistan, which soon escalated into a civil war that led to the formation of the independent state of Bangladesh. The Assembly was eventually opened when President Yahya resigned a few days later and PPP leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto took over. Bhutto became Prime Minister in 1973, after the post was recreated by the new Constitution.

Background

On 23 March 1956, Pakistan changed from being a Dominion of the British Commonwealth and became an Islamic republic after framing its own constitution. Although the first general elections were scheduled for early 1959, severe political instability led President Iskander Mirza to abrogate the constitution on 7 October 1958. Mirza imposed martial law and handed power to the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army, General Muhammad Ayub Khan. After assuming presidency, President Ayub Khan promoted himself to the rank of Field marshal and appointed General Muhammad Musa Khan as the new Commander-in-Chief.

On 17 February 1960, President Ayub Khan appointed a commission under Muhammad Shahabuddin, the Chief Justice of Pakistan, to report a political framework for the country. The commission submitted its report on 29 April 1961, and on the basis of this report, a new constitution was framed on 1 March 1962. The new constitution, declaring the country as Republic of Pakistan, brought about a presidential system of government, as opposed to the parliamentary system of government under the 1956 Constitution. The electoral system was made indirect, and the "basic democrats" were declared electoral college for the purpose of electing members of the National and Provincial Assemblies. Under the new system, presidential election were held on 2 February 1965 which resulted in a victory for Ayub Khan. As years went by, political opposition against President Ayub Khan mounted. In East Pakistan, leader of the Awami League, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was one of the key leaders to rally opposition to President Ayub Khan. In 1966, he began the Six point movement for East Pakistani autonomy.

In 1968, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was charged with sedition after the government of President Ayub Khan accused him for conspiring with India against the stability of Pakistan.[1] While a conspiracy between Mujib and India for East Pakistan's secession was not itself conclusively proven,[2] it is known that Mujib and the Awami League had held secret meetings with Indian government officials in 1962 and after the 1965 war.[3] This case led to an uprising in East Pakistan which consisted of a series of mass demonstrations and sporadic conflicts between the government forces and protesters.[1] In West Pakistan, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who served as foreign minister under President Ayub Khan, resigned from his office and founded the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) in 1967. The left-wing, socialist political party took up opposition to President Ayub Khan as well.

Ayub Khan succumbed to political pressure on 26 March 1969 and handed power to the Commander-in-Chief of the Pakistan Army, General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan. President Yahya Khan imposed martial law and the 1962 Constitution was abrogated. On 31 March 1970, President Yahya Khan announced a Legal Framework Order (LFO) which called for direct elections for a unicameral legislature. Many in the West feared the East wing's demand for countrywide provincial autonomy.[4] The purpose of the LFO was to secure the future Constitution which would be written after the election[5] so that it would include safeguards such as preserving Pakistan's territorial integrity and Islamic ideology.[6]

The integrated province of West Pakistan, which was formed on 22 November 1954, was abolished and four provinces were retrieved: Punjab, Sindh, Balochistan and the North-West Frontier Province. The principles of representation was made on the basis of population, and since East Pakistan had more population than the combined population of the four provinces of West Pakistan, the former got more than half seats in the National Assembly. Yahya Khan ignored reports that Sheikh Mujib planned to disregard the LFO and that India was increasingly interfering in East Pakistan.[7] Nor did he believe that the Awami League would actually sweep the elections in East Pakistan.[8]

A month before the election, the Bhola cyclone struck East Pakistan. This was the deadliest tropical cyclone in world history, killing on the order of 500,000 people. The Pakistan government was severely criticised for its response.

Parties and candidates

The general elections of 1970 are considered one of the fairest and cleanest elections in the history of Pakistan, with about twenty-four political parties taking part. The general elections presented a picture of a Two-party system, with the Awami League, a Bengali nationalist party, competing against the extremely influential and widely popular Pakistan Peoples Party, a leftist and democratic socialist party which had been a major power-broker in West Pakistan. The Pakistani government supported the pro-Islamic parties since they were committed to strong federalism.[9] The Jamaat-e-Islami suspected that the Awami League had secessionist intentions.[10]

Election campaign in East Pakistan

The continuous public meetings of the Awami League in East Pakistan and the Pakistan Peoples Party in Western Pakistan attracted huge crowds. The Awami League, a Bengali nationalist party, mobilised support in East Pakistan on the basis of its Six-Points Program (SPP), which was the main attraction in the party's manifesto. In East Pakistan, a huge majority of the Bengali nation favoured the Awami League, under Sheikh Mujib. The party received a huge percentage of the popular vote in East Pakistan and emerged as the largest party in the nation as a whole, gaining the exclusive mandate of Pakistan in terms both of seats and of votes.

The Pakistan Peoples Party failed to win any seats in East Pakistan. On the other hand, the Awami League had failed to gather any seats in West Pakistan. The Awami League's failure to win any seats in the west was used by the leftists and democratic socialists led by Zulfikar Bhutto who argued that Mujib had received "no mandate or support from West Pakistan" (ignoring the fact that he himself did not win any seat in East Pakistan).[11]

The then leaders of Pakistan, all from West Pakistan and PPP leaders, strongly opposed the idea of an East Pakistani-led government.[11] Many in Pakistan predicted that the Awami League-controlled government would oversee the passage of a new constitution with a simple majority.[11] Bhutto uttered his infamous phrase "idhar hum, udhar tum" (We rule here, you rule there) – thus dividing the Pakistan first time orally.[12]

The same attitudes and emotions were also felt in East Pakistan whereas East-Pakistanis absorbed the feeling and reached to the conclusion that Pakistan had been benefited with economic opportunities, investments, and social growth would swiftly depose any East Pakistanis from obtaining those opportunities.[11]

Some Bengalis sided with the Pakistan Peoples' Party and had voiced no support for the Awami League, supporting tacitly or openly Bhutto and the democratic socialists, such as Jalaludin Abdur Rahim, an influential Bengali in Pakistan and mentor of Bhutto[11] who was later thrown into jail by Bhutto, and Ghulam Azam of the Jamaat-e-Islami in East Pakistan.

Several notable people from West Pakistan supported handing over power to the Awami league, such as the poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz and rights activist Malik Ghulam Jilani, father of Asma Jahangir and G.M Syed the founder of Sindhi nationalist party Jeay Sindh Qaumi Mahaz (JSQM).

Elections in West Pakistan

However, the political position in West Pakistan was completely different from East Pakistan. In West Pakistan, the population was divided between different ideological forces. The right-wing parties, led under Abul Maududi, raised the religious slogans and initially campaigned on an Islamic platform, further promising to enforce Sharia laws in the country. Meanwhile, the founding party of Pakistan and the national conservative Muslim League, that although was divided into three factions (QML, CML, MLC), campaigned on a nationalist platform, promising to initiate the Jinnah reforms as originally envisioned by Jinnah and others in the 1940s. The factions however criticised each other for disobeying the rules laid down by the country's founding father.

The dynamic leadership and charismatic personality of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was highly active and influential in West Pakistan during these days. Bhutto's socialistic ideas and the famous slogan "Roti Kapra Aur Makaan" ("Food, Clothing and Shelter") attracted the poor communities, students, and working class. The democratic socialist, leftist, and marxist-communist masses gathered and united into one platform under Bhutto's leadership. Bhutto and the socialist-leftists appealed to the people of the West to participate and vote for the Peoples Party for a better future for their children and family. For the first time in the history of Pakistan, the leftists and democratic socialists, united under the leadership of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, participated in the elections as one strong power. As compared to the right-wing and conservatives in West Pakistan, Bhutto and his allied leftists and democratic socialists won most of the popular vote, becoming the pre-eminent players in the politics of the West.

Nominations

A total of 1,957 candidates filed nomination papers for 300 National Assembly seats. After scrutiny and withdrawals, 1,579 eventually contested the elections. The Awami League ran 170 candidates, of which 162 were for constituencies in East Pakistan. Jamaat-e-Islami had the second-highest number of candidates with 151. The Pakistan Peoples Party ran only 120 candidates, of which 103 were from constituencies in Punjab and Sindh, and none in East Pakistan. The PML (Convention) ran 124 candidates, the PML (Council) 119 and the PML (Qayyum) 133.

Voter turnout

The government claimed a high level of public participation and a voter turnout of almost 63%. The total number of registered voters in the country was 56,941,500 out of which 31,211,220 were from the Eastern Wing, while 25,730,280 from the Western Wing.

Results

National Assembly

| Party | Votes | % | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awami League | 12,937,162 | 39.2 | 160 |

| Pakistan Peoples Party | 6,148,923 | 18.6 | 81 |

| Jamaat-e-Islami | 1,989,461 | 6.0 | 4 |

| Council Muslim League | 1,965,689 | 6.0 | 2 |

| Muslim League (Qayyum) | 1,473,749 | 4.5 | 9 |

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam | 1,315,071 | 4.0 | 7 |

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan | 1,299,858 | 3.9 | 7 |

| Convention Muslim League | 1,102,815 | 3.3 | 7 |

| National Awami Party (W) | 801,355 | 2.4 | 6 |

| Pakistan Democratic Party | 737,958 | 2.2 | 1 |

| Other parties | 387,919 | 1.2 | 0 |

| Independents | 2,322,341 | 7.0 | 16 |

| Total | 33,004,065 | 100 | 300 |

| Nohlen et al.[13] | |||

Provincial Assemblies

East Pakistan

After all 300 constituencies had been declared, the results were:

| Party | Seats | Seat change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awami League (AL) | 288 | ||

| Pakistan Democratic Party (PDP) | 2 | ||

| National Awami Party (W) (NAP-W) | 1 | ||

| Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) | 1 | ||

| Others | 1 | ||

| Independents | 7 | ||

| Total | 300 | N/A | |

| ↓ | ||||

| 288 | 12 | |||

| AL | Other | |||

Punjab

After all 180 constituencies had been declared, the results were:

| Party | Seats | Seat change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) | 113 | ||

| Convention Muslim League (CML) | 15 | ||

| Muslim League (Qayyum) (QML) | 6 | ||

| Council Muslim League | 6 | ||

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (JUP) | 4 | ||

| Pakistan Democratic Party (PDP) | 4 | ||

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) | 2 | ||

| Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) | 1 | ||

| Others | 1 | ||

| Independent | 28 | ||

| Total | 180 | N/A | |

| ↓ | ||||

| 113 | 15 | 6 | 46 | |

| PPP | CML | QML | Other | |

Sindh

After all 60 constituencies had been declared, the results were:

| Party | Seats | Seat change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) | 28 | ||

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Pakistan (JUP) | 7 | ||

| Muslim League (Qayyum) (QML) | 5 | ||

| Convention Muslim League (CML) | 4 | ||

| Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) | 1 | ||

| Others | 1 | ||

| Independent | 14 | ||

| Total | 60 | N/A | |

| ↓ | ||||

| 28 | 7 | 5 | 12 | |

| PPP | JUP | QML | Other | |

North-West Frontier Province

After all 40 constituencies had been declared, the results were:

| Party | Seats | Seat change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Awami Party (W) (NAP-W) | 13 | ||

| Muslim League (Qayyum) (QML) | 10 | ||

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) | 4 | ||

| Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) | 3 | ||

| Council Muslim League | 2 | ||

| Convention Muslim League (CML) | 1 | ||

| Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) | 1 | ||

| Others | 0 | ||

| Independent | 6 | ||

| Total | 40 | N/A | |

| ↓ | ||||

| 13 | 10 | 4 | 13 | |

| NAP-W | QML | JI | Other | |

Balochistan

After all 20 constituencies had been declared, the results were:

| Party | Seats | Seat change | |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Awami Party (W) (NAP-W) | 8 | ||

| Muslim League (Qayyum) (QML) | 3 | ||

| Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI) | 2 | ||

| Others | 2 | ||

| Independent | 5 | ||

| Total | 20 | N/A | |

| ↓ | ||||

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 7 | |

| NAP-W | QML | JUI | Other | |

Aftermath

The elected Assembly initially did not meet as President Yahya Khan and the Pakistan Peoples Party did not want the majority party from East Pakistan forming government. This caused great unrest in East Pakistan which soon escalated into the call for independence on March 26, 1971 and ultimately led to war of independence with East Pakistan becoming the independent state of Bangladesh. The Assembly session was eventually held when Khan resigned four days after Pakistan surrendered in Bangladesh and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto took over. Bhutto became the Prime Minister of Pakistan in 1973, after the post was recreated by the new Constitution.

References

- 1 2 Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

The Agartala contacts however did not provide solid evidence of a Mujib-India secessionist conspiracy in East Pakistan

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

It is now clear that Mujib did hold secret discussions with local Indian leaders there in July 1962. Moreover, following the 1965 war there were meetings between Awami League leaders and representatives of the Indian Government at a number of secret locations.

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

When this duly arrived. the western wing's nightmare scenario materialised: either a constitutional deadlock, or the imposition in the whole of the country of the Bengalis' longstanding commitment to unfettered democracy and provincial autonomy.

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

Yahya had made some provision to safeguard the constitutional outcome through the promulgation of the Legal Framework Order (LFO) on 30 March 1970. It set a deadline of 120 days for the framing of a constitution by the National Assembly and reserved to the President the right to authenticate it.

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

It would also have to enshrine the following five principles: an Islamic ideology...and internal affairs and the preservation of the territorial integrity of the country

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

He also refused to countenance intelligence service reports both of Mujib's aim to tear up the LFO after the elections and establish Bangladesh and of India's growing involvement in the affairs of East Pakistan.

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 193. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

From November 1969 until the announcement of the national election results, he discounted the possibility of an Awami League landslide in East Pakistan.

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

The regime also increasingly favoured the Islam pasand (Islam loving) parties because of their conservatism and attachment to the idea of a strong central government

- ↑ Ian Talbot (1998). Pakistan: A Modern History. St. Martin's Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-312-21606-1.

The JI itself warned that an Awami League victory would mean the disintegration of Pakistan.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Owen Bennett-Jones (2003). Pakistan: Eye of the Storm. Yale University Press. pp. 146–180. ISBN 978-0-300-10147-8.

- ↑ "Idhar hum, udhar tum: Abbas Athar remembered - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2017-04-24.

- ↑ Dieter Nohlen, Florian Grotz & Christof Hartmann (2001) Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume I, p686 ISBN 0-19-924958-X