Nāga

%2C_Badami_Hindu_cave_temple_Karnataka.jpg) 6th century Naga at Badami cave temples | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Water deity, Tutelary deity, Snake deity |

| Similar creatures | Dragon (related to the Chinese dragon, Japanese dragon, Korean dragon, Vietnamese dragon and Druk) and Bakunawa |

| Mythology | Hindu mythology and Buddhist mythology |

| Other name(s) | Nāgī or Nāginī |

| Country | India |

| Region | South Asia and Southeast Asia |

| Habitat | Underworld, Lakes, rivers, ponds, sacred groves and caves |

Naga (IAST: nāga; Devanāgarī: नाग) or Nagi (f. of nāga; IAST: nāgī; Devanāgarī: नागी)[1] is a Sanskrit word which basically refers to a "serpent" or "snake", especially the King cobra. The term Naga in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism denotes divine, semi-divine deities, or a semi-divine race of half-human half-serpent beings that resides in the heavenly Patala (netherworld) and can occasionally take human form. They are principally depicted in three forms: wholly humans with snakes on the heads and necks; common serpents or as half-human half-snake beings.[2] A female naga is a "nagi", "nagin", or "nagini". Nagaraja is seen as the king of nāgas and nāginis.[3]

Etymology

| Wikispecies has information related to Naja naja |

In Sanskrit, a nāgá (नाग) is a cobra, the Indian cobra (Naja naja). A synonym for nāgá is phaṇin (फणिन्). There are several words for "snake" in general, and one of the very commonly used ones is sarpá (सर्प). Sometimes the word nāgá is also used generically to mean "snake".[4] The word is cognate with English 'snake', Germanic: *snēk-a-, Proto-IE: *(s)nēg-o- (with s-mobile).[5]

Hinduism

The mythological serpent race that took form as cobras often can be found in Hindu iconography. The nāgas are described as the powerful, splendid, wonderful and proud semidivine race that can assume their physical form either as human, partial human-serpent or the whole serpent. Their domain is in the enchanted underworld, the underground realm filled with gems, gold and other earthly treasures called Naga-loka or Patala-loka. They are also often associated with bodies of waters — including rivers, lakes, seas, and wells — and are guardians of treasure.[6] Their power and venom made them potentially dangerous to humans. However, they often took beneficial protagonist role in Hindu mythology, such as in Samudra manthan mythology, Vasuki, a nāgarāja who abides on Shiva's neck, became the churning rope for churning of the Ocean of Milk.[7] Their eternal mortal enemies are the Garudas, the legendary semidivine birdlike-deity.[8]

Vishnu is originally portrayed in the form sheltered by Śeṣanāga or reclining on Śeṣa, but the iconography has been extended to other deities as well. The serpent is a common feature in Ganesha iconography and appears in many forms: around the neck,[9] use as a sacred thread (Sanskrit: yajñyopavīta)[10] wrapped around the stomach as a belt, held in a hand, coiled at the ankles, or as a throne.[11] Shiva is often shown garlanded with a snake.[12] Maehle (2006: p. 297) states that "Patanjali is thought to be a manifestation of the serpent of eternity".

Buddhism

As in Hinduism, the Buddhist nāga generally has the form of a great cobra, usually with a single head but sometimes with many. At least some of the nāgas are capable of using magic powers to transform themselves into a human semblance. The nāga is sometimes portrayed as a human being with a snake or dragon extending over his head.[13] One nāga, in human form, attempted to become a monk; and when telling it that such ordination was impossible, the Buddha told it how to ensure that it would be reborn a human, and so able to become a monk.[14]

In the "Devadatta" chapter of the Lotus Sutra, the daughter of the dragon king, an eight year old longnü (nāga), after listening to Mañjuśrī preach the Lotus Sutra, transforms into a male Bodhisattva and immediately reaches full enlightenment.[15][16][17] This tale appears to reinforce the viewpoint prevalent in Mahayana scriptures that a male body is required for Buddhahood, even if a being is so advanced in realization that they can magically transform their body at will and demonstrate the emptiness of the physical form itself.[18]

Nagas are believed to both live on Mount Meru, among the other minor deities, and in various parts of the human-inhabited earth. Some of them are water-dwellers, living in streams or the ocean; others are earth-dwellers, living in underground caverns.

The nāgas are the followers of Virūpākṣa (Pāli: Virūpakkha), one of the Four Heavenly Kings who guards the western direction. They act as a guard upon Mount Sumeru, protecting the dēvas of Trāyastriṃśa from attack by the asūras.

Among the notable nāgas of Buddhist tradition is Mucalinda, Nāgarāja and protector of the Buddha. In the Vinaya Sutra (I, 3), shortly after his enlightenment, the Buddha is meditating in a forest when a great storm arises, but graciously, King Mucalinda gives shelter to the Buddha from the storm by covering the Buddha's head with his seven snake heads.[19] Then the king takes the form of a young Brahmin and renders the Buddha homage.[19]

It is noteworthy that the two chief disciples of the Buddha, Sariputta and Moggallāna are both referred to as Mahānāga or "Great Nāga".[20] Some of the most important figures in Buddhist history symbolize nagas in their names such as Dignāga, Nāgāsēna, and, although other etymons are assigned to his name, Nāgārjuna.

In the Vajrayāna and Mahāsiddha traditions,[21] nagas in their half-human form are depicted holding a naga-jewel, kumbhas of amrita, or a terma that had been elementally encoded by adepts.

According to tradition, Prajñapāramita sutras had been given by the Buddha to a great Naga who guarded them in the sea, and were conferred upon Nāgārjuna later.[22][23]

Other traditions

In Thailand and Java, the nāga is a wealthy underworld deity. For Malay sailors, nāgas are a type of dragon with many heads. In Laos they are beaked water serpents.

Cambodia

The seven-headed nagas often depicted as guardian statues, carved as balustrades on causeways leading to main Cambodian temples, such as those found in Angkor Wat.[24] Apparently they represent the seven races within naga society, which has a mythological, or symbolic, association with "the seven colors of the rainbow". Furthermore, Cambodian naga possess numerological symbolism in the number of their heads. Odd-headed naga symbolise the Male Energy, Infinity, Timelessness, and Immortality. This is because, numerologically, all odd numbers come from One (1). Even-headed naga are said to be "Female, representing Physicality, Mortality, Temporality, and the Earth."

Indonesia

In Javanese and Balinese culture, Indonesia, a naga is depicted as a crowned, giant, magical serpent, sometimes winged. It is similarly derived from the Shiva-Hinduism tradition, merged with Javanese animism. Naga in Indonesia mainly derived and influenced by Indic tradition, combined with the native animism tradition of sacred serpents. In Sanskrit the term naga literally means snake, but in Java it normally refer to serpent deity, associated with water and fertility. In Borobudur, the nagas are depicted in their human form, but elsewhere they are depicted in animal shape.[25]

Early depictions of circa-9th-century Central Java closely resembled Indic Naga which was based on cobra imagery. During this period, naga serpent are depicted as a giant cobra supported the waterspout of yoni-lingam. The examples of naga sculpture can be found in several Javanese candis, including Prambanan, Sambisari, Ijo, and Jawi. In East Java, the Penataran temple complex contain a Candi Naga, an unusual naga temple with its Hindu-Javanese caryatids holding corpulent nagas aloft.[26]

The later depiction since the 15th century, however, was slightly influenced by Chinese dragon imagery—although unlike its Chinese counterparts, Javanese and Balinese nagas do not have legs. Naga as the lesser deity of earth and water is prevalent in the Hindu period of Indonesia, before the introduction of Islam.

In Balinese tradition, nagas are often depicted battling Garuda. Intricately carved naga are found as stairs railings in bridges or stairs, such as those found in Balinese temples, Ubud monkey forest, and Taman Sari in Yogyakarta.

In a wayang theater story, a snake (naga) god named Sanghyang Anantaboga or Antaboga is a guardian deity in the bowels of the earth.[27][28] Naga symbolize the nether realm of earth or underworld.

Laos

Naga are believed to live in the Laotian stretch of the Mekong or its estuaries. Lao mythology maintains that the naga are the protectors of Vientiane, and by extension, the Lao state. The naga association was most clearly articulated during and immediately after the reign of Anouvong. An important poem from this period San Leupphasun (Lao: ສານລຶພສູນ) discusses relations between Laos and Thailand in a veiled manner, using the naga and the garuda to represent the Lao and the Thai, respectively.[29] The naga is incorporated extensively into Lao iconography, and features prominently in Lao culture throughout the length of the country, not only in Vientiane.

Malaysia

In Malay and Orang Asli traditions, the lake Chini, located in Pahang is home to a naga called Sri Gumum. Depending on legend versions, her predecessor Sri Pahang or her son left the lake and later fought a naga called Sri Kemboja. Kemboja is the Malay name for Cambodia. Like the naga legends there, there are stories about an ancient empire in lake Chini, although the stories are not linked to the naga legends.[30][31]

Notable nāgas

- Vasuki, the king of nagas and who coils over the Shiva's neck[32]

- Naga Seri Gumum, who lives in Tasik Chini, a freshwater lake in Pahang, Malaysia

- Ananta-Sesha, on whom Vishnu is in yoga nidra (Ananta shayana)[33]

- Bakunawa, a dragon in Philippine mythology that is often represented as a gigantic sea serpent. Nagas are also present in Kapampangan polytheistic beliefs, such as Lakandanum. (See Deities of Philippine mythology.)

- Kaliya, a snake conquered by Krishna

- Karkotaka, a naga king in Indian mythology who controls weather, that lived in a forest near Nishada Kingdom and bit Nala at the request of Indra controls weather

- Manasa, the Hindu goddess of Nagas and curer of snake-bite and sister of Vasuki

- Mucalinda, a nāga in Buddhism who protected the Gautama Buddha from the elements after his enlightenment

- Padmavati, the Nāgī queen & companion of Dharanendra

- Paravataksha, his sword causes earthquakes and his roar caused thunder.

- Shwe Nabay (Naga Medaw), a goddess or a Nat spirit in Burmese animistic mythology, who is believed to have married a Naga and died from heartbreak after he left her

- Takshaka, the tribal king of the nagas

- Ulupi, a companion of Arjuna in the epic Mahabharata

- Yulong, the Dragon King of the West Sea in the Chinese classical novel Journey to the West, becomes a naga after completing his journey with Xuanzang

In popular culture

- Several Bollywood films have been made about female nāgas, including Nagin (1954), Nagin (1976), Nagina (1986), Nigahen (1989), Jaani Dushman: Ek Anokhi Kahani (2002), Hisss (2010), and the television series Naaginn (2007-2009).

- In Jungle Boy, the Naga is depicted as a large cobra deity that grants the gift of understanding all languages to those who are pure of heart and punishes those who aren't pure of heart in different ways.

- The Nagas are antagonists in the cartoon The Secret Saturdays. They served the ancient Sumerian cryptid Kur and attempted to push Zak Saturday into the dark side after learning that he was Kur reincarnated, but eventually served V.V. Argost when he gained his own Kur powers.

- The Nagas appear in the Warcraft franchise. They are depicted as ancient night elves that have snake-like tails in place of legs, and have other serpentine features such as scales and fins. The Nagas came to be when they were transformed from the ancient night elves by the Old Gods.

- Magic: The Gathering's 2014-2015 block, set on the plane of Tarkir, featured Naga as humanoid snakes versed in powerful venoms and poisons with two arms and no other appendages. They are aligned with the Sultai clan in the sets, Khans of Tarkir[34] and Fate Reforged,[35] and with the Silumgar clan in the Dragons of Tarkir[36] set.

Gallery

Naga and Nagini in Bhuvanesvar, Odisha

Naga and Nagini in Bhuvanesvar, Odisha Naga on copper pillar in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh India

Naga on copper pillar in Kullu, Himachal Pradesh India Naga king in Anjali mudra in Deogarh temple, Madhya Pradesh

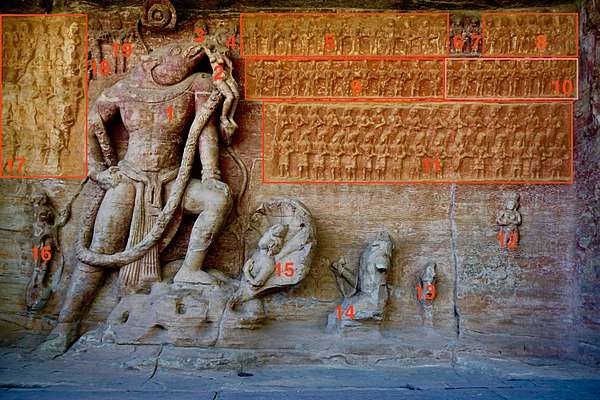

Naga king in Anjali mudra in Deogarh temple, Madhya Pradesh Naga (marked 15) in the Varaha panel at Udayagiri Caves

Naga (marked 15) in the Varaha panel at Udayagiri Caves Tirthankara Parshvanatha of Jainism standing under Naga hood

Tirthankara Parshvanatha of Jainism standing under Naga hood Naga supporting waterspout of Yoni-Lingam, Yogyakarta Java, c. 9th century

Naga supporting waterspout of Yoni-Lingam, Yogyakarta Java, c. 9th century.jpg) Naga temple, Penataran, East Java

Naga temple, Penataran, East Java.jpg) Naga bridge at Ubud monkey forest, Bali

Naga bridge at Ubud monkey forest, Bali

- Sesa Naga at Bangkok international airport, Thailand

Naga at the funeral of King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand in 2017

Naga at the funeral of King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand in 2017

See also

- Bakunawa

- Basilisk

- Chinese dragon

- Deities of Philippine mythology

- European dragon

- Horned Serpent

- Ichchhadhari Nag

- Lamia

- Lilith

- Makara

- Naga people (Lanka)

- Nagaradhane

- Nagarjuna

- Nagavanshi

- Pillai (Kerala title)

- Nair

- Padmanabhaswamy Temple

- Oarfish

- Rainbow Serpent

- List of reptilian humanoids

- Sea serpent

- Serpent (symbolism)

- Shapeshifting

- Snake worship

- Shahmaran

- Yamata no Orochi

References

- ↑ "Sanskrit Dictionary". sanskritdictionary.com. Retrieved 2018-09-27.

- ↑ Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 300. ISBN 9780816075645.

- ↑ Elgood, Heather (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. London: Cassell. p. 234. ISBN 0-304-70739-2.

- ↑ Apte, Vaman Shivram (1997). The student's English-Sanskrit dictionary (3rd rev. & enl. ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0299-3. , p. 423. The first definition of nāgaḥ given reads "A snake in general, particularly the cobra." p.539

- ↑ Proto-IE: *(s)nēg-o-, Meaning: snake, Old Indian: nāgá- m. 'snake', Germanic: *snēk-a- m., *snak-an- m., *snak-ō f.; *snak-a- vb.: "Indo-European etymology".

- ↑ "Naga | Hindu mythology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Why was vasuki used in Samudra Manthan great ocean Churning". Hinduism Stack Exchange. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Garuda | Hindu mythology". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ For the story of wrapping Vāsuki around the neck and Śeṣa around the belly and for the name in his sahasranama as Sarpagraiveyakāṅgādaḥ ("Who has a serpent around his neck"), which refers to this standard iconographic element, see: Krishan, Yuvraj (1999), Gaņeśa: Unravelling An Enigma, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 81-208-1413-4, pp=51-52.

- ↑ For text of a stone inscription dated 1470 identifying Ganesha's sacred thread as the serpent Śeṣa, see: Martin-Dubost, p. 202.

- ↑ For an overview of snake images in Ganesha iconography, see: Martin-Dubost, Paul (1997). Gaņeśa: The Enchanter of the Three Worlds. Mumbai: Project for Indian Cultural Studies. ISBN 81-900184-3-4, p. 202.

- ↑ Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0. ; p. 151

- ↑ "Indian Nagas and Draconic Prototypes" in: Ingersoll, Ernest, et al., (2013). The Illustrated Book of Dragons and Dragon Lore. Chiang Mai: Cognoscenti Books. ASIN B00D959PJ0

- ↑ Brahmavamso, Ajahn. "VINAYA The Ordination Ceremony of a Monk".

- ↑ Schuster, Nancy (1981). Changing the Female Body: Wise Women and the Bodhisattva Career in Some Mahāratnakūṭasūtras, Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies 4 (1), 42-43

- ↑ Kubo Tsugunari, Yuyama Akira (tr.). The Lotus Sutra. Revised 2nd ed. Berkeley, Calif. : Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, 2007. ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9, pp. 191-192

- ↑ Soka Gakkai Dictionary of Buddhism, "Devadatta Chapter"

- ↑ Peach, Lucinda Joy (2002). Social responsibility, sex change, and salvation: Gender justice in the Lotus Sūtra, Philosophy East and West 52,55-56

- 1 2 P. 72 How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings By Richard Francis Gombrich

- ↑ P. 74 How Buddhism Began: The Conditioned Genesis of the Early Teachings By Richard Francis Gombrich

- ↑ Béer 1999, p. 71.

- ↑ Thomas E. Donaldson (2001). Iconography of the Buddhist Sculpture of Orissa: Text. Abhinav Publications. p. 276. ISBN 978-81-7017-406-6.

- ↑ Tāranātha (Jo-nang-pa) (1990). Taranatha's History of Buddhism in India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 384. ISBN 978-81-208-0696-2.

- ↑ Rosen, Brenda (2009). The Mythical Creatures Bible: The Definitive Guide to Legendary Beings. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. ISBN 9781402765360.

- ↑ Miksic, John (2012-11-13). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462909100.

- ↑ Kinney, Ann R.; Klokke, Marijke J.; Kieven, Lydia (2003). Worshiping Siva and Buddha: The Temple Art of East Java. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824827793.

- ↑ Susanne Rodemeier: Lego-lego Platz und naga-Darstellung. Jenseitige Kräfte im Zentrum einer Quellenstudie über die ostindonesische Insel Alor. (Magisterarbeit 1993) Universität Passau 2007

- ↑ Heinrich Zimmer: Indische Mythen und Symbole. Diederichs, Düsseldorf 1981, ISBN 3-424-00693-9

- ↑ Ngaosīvat, Mayurī; Pheuiphanh Ngaosyvathn (1998). Paths to conflagration : fifty years of diplomacy and warfare in Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam, 1778-1828. Studies on Southeast Asia. 24. Ithaca, N.Y.: Southeast Asia Program Publications, Cornell University. p. 80. ISBN 0-87727-723-0. OCLC 38909607.

- ↑ Legends Archived 24 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Journey Malaysia » Tasik Chini". journeymalaysia.com.

- ↑ Bhāgavata Purāṇa 3.26.25

- ↑ Bhāgavata Purāṇa 10.1.24

- ↑ "Planeswalker's Guide to Khans of Tarkir, Part 1". MAGIC: THE GATHERING. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ "Planeswalker's Guide to Fate Reforged". MAGIC: THE GATHERING. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ "Planeswalker's Guide to Dragons of Tarkir, Part 1". MAGIC: THE GATHERING. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

Further reading

- Béer, Robert (1999), The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs, Shambhala, ISBN 978-1-57062-416-2

- Müller-Ebeling, Claudia; Rätsch, Christian; Shahi, Surendra Bahadur (2002), Shamanism and Tantra in the Himalayas, Inner Traditions, ISBN 9780892819133

- Maehle, Gregor (2007), Ashtanga Yoga: Practice and Philosophy, New World Library, ISBN 978-1-57731-606-0

- Norbu, Chögyal Namkhai (1999), The Crystal and The Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen, Snow Lion Publications, ISBN 1-55939-135-9

- Hāṇḍā, Omacanda (2004), Naga cults and traditions in the western Himalaya, Indus Publishing, ISBN 9788173871610

- Visser, Marinus Willem de (1913), The dragon in China and Japan, Amsterdam:J. Müller

- Vogel, J. Ph. (1926), Indian serpent-lore; or, The Nāgas in Hindu legend and art, London, A. Probsthain, ISBN 9788120610712

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nāga. |

- Nagas in the Pali Canon

- Nagas

- Image of a Seven-Headed Naga

- Nagas and Serpents

- Depictions of Nagas in the area of Angkor Wat in Cambodia

- Nagas and Naginis: Serpent Figures in Hinduism and Buddhism