Ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

|

Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

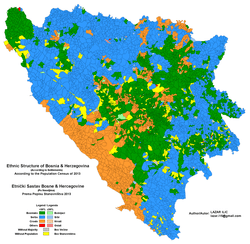

More than 96% of population of Bosnia and Herzegovina belongs to one of its three autochthonous constituent nations: Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats. The term constituent refers to the fact that these three ethnic groups are explicitly mentioned in the constitution, and that none of them can be considered a minority or immigrant. The most easily recognizable feature that distinguishes the three ethnic groups is their religion, with Bosniaks predominantly Muslim, Serbs predominantly Orthodox Christians, and Croats Catholic.

While each ethnic group have their own standard language variant and a name for it, they speak, depending on view, one pluricentric language or three mutually intelligible languages. On a dialectal level, Serbs, Croats and Bosniaks speak a variety of Shtokavian dialects which have fixed phonetic, morphological and lexical minor differences. The question of standard language is resolved in such a way that three constituent ethnic groups have their educational and cultural institutions in their respective native or mother tongue languages: Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian.

A Y chromosome haplogroups study published in 2005 found that "three main groups of Bosnia-Herzegovina, in spite of some quantitative differences, share a large fraction of the same ancient gene pool distinctive for the Balkan area". The study did however find that Serbs and Bosniaks are genetically closer to each other than either of them is to Croats.[1]

Decision of the Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina

On 12 February 1998, Alija Izetbegović, at the time Chair of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina, instituted proceedings before the Constitutional Court for an evaluation of the consistency of the Constitution of the Republika Srpska and the Constitution of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The request was supplemented on 30 March 1998 when the applicant specified which provisions of the Entities' Constitutions he considered to be unconstitutional.

The four partial decisions were made in 2000, by which many of articles of the constitutions of entities were found to be unconstitutional, which had a great impact on the politics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, because there was a need to adjust the current state in the country with the decision of the Court. A narrow majority (5-4) ruled in favour of the applicant. In its decision, among other things, the Court stated:

Elements of a democratic state and society as well as underlying assumptions – pluralism, just procedures, peaceful relations that arise out of the Constitution – must serve as a guideline for further elaboration of the issue of the structure of BiH as a multi-national state. Territorial division (of Entities) must not serve as an instrument of ethnic segregation – on the contrary – it must accommodate ethnic groups by preserving linguistic pluralism and peace in order to contribute to the integration of the state and society as such. Constitutional principle of collective equality of constituent peoples, arising out of designation of Bosniacs, Croats and Serbs as constituent peoples, prohibits any special privileges for one or two constituent peoples, any domination in governmental structures and any ethnic homogenisation by segregation based on territorial separation. Despite the territorial division of BiH by establishment of two Entities, this territorial division cannot serve as a constitutional legitimacy for ethnic domination, national homogenisation or the right to maintain results of ethnic cleansing. Designation of Bosniacs, Croats and Serbs as constituent peoples in the Preamble of the Constitution of BiH must be understood as an all-inclusive principle of the Constitution of BiH to which the Entities must fully adhere, pursuant to Article III.3 (b) of the Constitution of BiH.[2]

The formal name of this item is U-5/98, but it is widely known as the "Decision on the constituency of peoples" (Bosnian: Odluka o konstitutivnosti naroda), referring to the Court's interpretation of the significance of the phrase "constituent peoples" used in the Preamble of the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The decision was also the basis for other notable cases that came before the court.

Historical background

Some argue that a Bosnian identity (in the non-religious sense) goes back centuries, the Serb and Croat for Christian Bosnians a century, and Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) even more recently.[3]

During the Ottoman Empire, the term Boşnak was used to describe Bosnians (of the Bosnia Eyalet) in an ethnic or "tribal" sense. After the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1878, the Austrian administration officially endorsed Bosnianhood as the basis of a multi-confessional Bosnian nation. The policy aspired to isolate Bosnia and Herzegovina from its irredentist neighbors (Orthodox Serbia, Catholic Croatia, and the Muslims of the Ottoman Empire) and to negate the concept of Croatian and Serbian nationhood which had already begun to take ground among Bosnia and Herzegovina's Catholic and Orthodox communities, respectively.[4]

In the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes were the constituent ("old") nations.[5] During the reign of King Aleksandar I, a modern single Yugoslav identity was unsuccessfully propagated to erase the particularistic identities.[6] With the formation of Socialist Yugoslavia, there were six republics and five constitutive nations, adding Macedonians and Montenegrins (whose identities were not earlier recognized); the Bosnian Muslims were recognized only in the late 1960s.[7]

For the 1961 census a new ethnic category was introduced–Muslims–with which 972,954 Bosnians identified.[8] In 1964, the Muslims were declared a narod ("people"), as the other five "peoples", but were not ascribed a national republic.[8] In 1968, the Bosnian Central Committee declared that "...Muslims are a distinct nation". For the 1971 census, accordingly, "Muslims, in the sense of a nation" was introduced.[8]

Inter-ethnic relations

Serbs tend to be Orthodox Christian, Croats tend to be Roman Catholic, and Bosniaks (or Bosnian Muslims) tend to be Sunni Muslim. Tensions between these were expressed in terms of religion. Fundamentalists existed on all sides; in propaganda the Bosnian War took on some features of a "religious war", supported by views of religious leaders. Historical stereotypes and prejudice were further established by experiences of war. The situation still impedes the development of relations post-war. Religious symbols are used for nationalist purposes.[9]

Official language

Demographic history

See also

References

- ↑ Marjanović, D; Fornarino, S; Montagna, S; et al. (2005). "The peopling of modern Bosnia-Herzegovina: Y-chromosome haplogroups in the three main ethnic groups". Annals of Human Genetics. 69 (Pt 6): 757–63. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00190.x. PMID 16266413.

- ↑ Constitutional Court of Bosnia and Herzegovina, U-5/98 (Partial Decision Part 3), p. 36, Sarajevo, 1 July 2000.

- ↑ Donia & Fine 1994, p. 73

A Bosnian's identity as a Bosnian - even if it originally referred to his geographical homeland or state membership - has roots going back many centuries, whereas the classification of any Christian Bosnian as a Serb or a Croat goes back barely a century. The idea of being Bosnian Muslim in a "national" (as opposed to a religious) sense is even more recent.

- ↑ See Donia & Fine 1994, pp. ?, Eller 1999, p. 262, Velikonja 2003, pp. 130–135

- ↑ Jović 2009, p. 320.

- ↑ Nielsen 2014.

- ↑ Jović 2009, pp. 48, 57.

- 1 2 3 Eller 1999, p. 282.

- ↑ Fischer 2006, p. 21.

Sources

- Donia, Robert J.; Fine, John Van Antwerp, Jr. (1994). Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-212-0.

- Eller, Jack David (1999). "Bosnia". From Culture to Ethnicity to Conflict: An Anthropological Perspective on International Ethnic Conflict. University of Michigan Press. pp. 243–. ISBN 0-472-08538-7.

- Fischer, Martina, ed. (2006). Peacebuilding and Civil Society in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ten Years After Dayton. Berghof Forschungszentrum für Konstruktive Konfliktbearbeitung; LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 21–. ISBN 978-3-8258-8793-3.

- Jović, Dejan (2009). Yugoslavia: A State that Withered Away. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-495-8.

- Puhalo, S. (2003). "Etnička distanca građana Republike Srpske i Federacije BiH prema narodima bivše SFRJ". Psihologija. 36 (2): 141–156. doi:10.2298/PSI0302141P.

- Danijela Majstorovic; Vladimir Turjacanin (1 January 2013). Youth Ethnic and National Identity in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Social Science Approaches. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-46717-4.

- Nielsen, Christian Axboe (2014). Making Yugoslavs: Identity in King Aleksandar's Yugoslavia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-2750-5.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-60344-724-9.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina. |

- Kofman, Daniel (2001). "Self-determination in a multiethnic state: Bosnians, Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs". Reconstructing multiethnic societies: the case of Bosnia-Herzegovina: 31–62.