Mike Mansfield

| Mike Mansfield | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Ambassador to Japan | |

|

In office June 10, 1977 – December 22, 1988 | |

| President |

Jimmy Carter Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | James D. Hodgson |

| Succeeded by | Michael Armacost |

| Senate Majority Leader | |

|

In office January 3, 1961 – January 3, 1977 | |

| Deputy |

Hubert Humphrey Russell B. Long Ted Kennedy Robert Byrd |

| Preceded by | Lyndon B. Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Robert Byrd |

| Senate Majority Whip | |

|

In office January 3, 1957 – January 3, 1961 | |

| Leader | Lyndon Johnson |

| Preceded by | Earle C. Clements |

| Succeeded by | Hubert Humphrey |

| United States Senator from Montana | |

|

In office January 3, 1953 – January 3, 1977 | |

| Preceded by | Zales Ecton |

| Succeeded by | John Melcher |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Montana's 1st district | |

|

In office January 3, 1943 – January 3, 1953 | |

| Preceded by | Jeannette Rankin |

| Succeeded by | Lee Metcalf |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Michael Joseph Mansfield March 16, 1903 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

October 5, 2001 (aged 98) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Maureen Hayes |

| Children | 1 daughter |

| Education |

University of Montana, Tech University of Montana, Missoula (BA, MA) University of California, Los Angeles |

| Signature |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service |

1918–1919 (Navy) 1919–1920 (Army) 1920–1922 (Marine Corps) |

| Rank |

Seaman (Navy) Private (Army) Private First Class (Marine Corps) |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

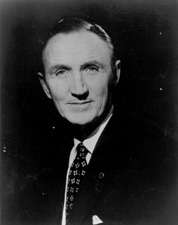

Michael Joseph Mansfield (March 16, 1903 – October 5, 2001) was an American politician and diplomat. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as a U.S. Representative (1943–1953) and a U.S. Senator (1953–1977) from Montana. He was the longest-serving Senate Majority Leader, serving from 1961–1977. During his tenure, he shepherded Great Society programs through the Senate and strongly opposed the Vietnam War.

Born in Brooklyn, Mansfield grew up in Great Falls, Montana. He lied about his age to serve in the United States Navy during World War I. After the war, he became a professor of history and political science at the University of Montana. He won election to the House of Representatives and served on the House Committee on Foreign Affairs during World War II.

In 1952, he defeated incumbent Republican Senator Zales Ecton to take a seat in the Senate. Mansfield served as Senate Majority Whip from 1957 to 1961. Mansfield ascended to Senate Majority Leader after Lyndon B. Johnson resigned from the Senate to become vice president. He opposed escalation of the Vietnam War and supported President Richard Nixon's plans to withdraw U.S. soldiers from Southeast Asia.

After retiring from the Senate, Mansfield served as U.S. Ambassador to Japan from 1977 to 1988. Upon retiring as ambassador, he was awarded the nation's highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, in part for his role in the resignation of President Nixon.[1] Mansfield is the longest-serving American ambassador to Japan in history.[2] After his ambassadorship, Mansfield served for a time as a senior adviser on East Asian affairs to Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street investment banking firm.[1]

Early childhood

Mansfield was born in the Brooklyn borough of New York City, the son of Patrick J. Mansfield and Josephine (née O'Brien) Mansfield,[3] who were both Irish Catholic immigrants.[4] His mother died from pneumonia in 1906, and his father subsequently sent Michael and his two sisters to live with an aunt and uncle in Great Falls, Montana.[5] He attended local public schools, and worked in his relatives' grocery store.[4] He turned into a habitual runaway, even living at a state orphanage in Twin Bridges for half a year.[6]

Military service

At 14, Mansfield dropped out of school and lied about his age in order to enlist in the U.S. Navy during World War I.[7] He went on several overseas convoys on the USS Minneapolis, but was discharged by the Navy after his real age was discovered.[7] (He was the last known veteran of the war to die before reaching the age of 100, as well as being the final World War I veteran to sit in the US Senate.) After his Navy discharge, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, serving as a private from 1919 to 1920.[8]

Mansfield was a Private First Class in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1920 to 1922.[8] He served in the Western Recruiting Division at San Francisco until January 1921, when he was transferred to the Marine Barracks at Puget Sound, Washington. The following month, he was detached to the Guard Company, Marine Barracks, Navy Yard, Mare Island, California. In April, he boarded the USAT Sherman, bound for the Philippines. After a brief stopover at the Marine Barracks at Cavite, he arrived at his duty station on May 5, 1921, the Marine Barracks, Naval Station, Olongapo, Philippine Islands. One year later, Mansfield was assigned to Company A, Marine Battery, Asiatic Fleet. A short tour of duty with the Asiatic Fleet took him along the coast of China, before he returned to Olongapo in late May 1922.[7] His service with the Marines established a lifelong interest in Asia.

That August, Mansfield returned to Cavite in preparation for his return to the United States and eventual discharge. On November 9, 1922, Marine Private Michael J. Mansfield was released on the completion of his enlistment. He was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, his character being described as "excellent" during his two years as a Marine.

Education

Following his return to Montana in 1922, Mansfield worked as a "mucker," shoveling ore and other waste in the copper mines of Butte for eight years.[8] Having never attended high school, he took entrance examinations to attend the Montana School of Mines (1927–1928), studying to become a mining engineer.[6] He later met a local schoolteacher and his future wife, Maureen Hayes, who encouraged him to further his education. With her financial support, Mansfield studied at the University of Montana in Missoula, where he took both high school and college courses.[5] He was also a member of Alpha Tau Omega fraternity. He earned his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1933, and was offered a graduate assistantship teaching two courses at the university; he also worked part-time in the registrar's office.[4] He earned a Master of Arts degree from the University of Montana in 1934 with a thesis entitled: "American Diplomatic Relations with Korea, 1866–1910". From 1934 to 1942, he taught classes in Far Eastern and Latin American history, and also lectured some years on Greek and Roman history.[6] He also attended the University of California at Los Angeles (1936–1937).[8]

Service in House of Representatives

In 1940, Mansfield ran for the Democratic nomination for the U.S. House of Representatives in Montana's 1st congressional district but was defeated by Jerry J. O'Connell, a former holder of the seat, in the primary; the general election was won by Republican Jeannette Rankin, who had previously won what was formerly an at-large seat in the House in 1918 and served until her defeat in 1920.[7] Mansfield decided to run for the seat again in the following election and won it by defeating businessman Howard K. Hazelbaker after Rankin, who had voted against the entry of the United States into World War II, decided not to run for what would have been her third term.[9]

A confidential 1943 analysis of the House Foreign Affairs Committee by Isaiah Berlin for the British Foreign Office described Mansfield as[10]

A new-comer to the House, who is reportedly internationalist-minded, having been professor of history and political science at Montana State University for ten years. Though a supporter of the Administration's foreign policy, he is likely to be strongly critical of the smallness of China's share of Lend-Lease, and of what he fears is the Administration's tendency to regard the Atlantic as more important than the Pacific, and of its apparent reluctance to regard the Chinese as an ally on equal footing. His strongly pro-Chinese sentiments may tend to make him somewhat anti-British on this score.

Mansfield served five terms in the House, being re-elected in 1944, 1946, 1948, and 1950. His military service and academic experience landed him a seat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee.[4] He went to China on a special mission for President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944 and served as a delegate to the ninth Inter-American Conference in Colombia in 1948.[9] In 1951, he was appointed by President Harry S. Truman as a delegate to the United Nations' sixth session in Paris. During his House tenure, he also expressed his support for price controls, a higher minimum wage, the Marshall Plan, and aid to Turkey and Greece. He opposed the House Un-American Activities Committee, the Taft–Hartley Act, and the Twenty-second Amendment.[9]

U.S. Senator

In 1952, Mansfield was elected to the U.S. Senate after narrowly defeating Republican incumbent Zales Ecton.[7] He served as Senate Majority Whip under Majority Leader Lyndon B. Johnson from 1957 to 1961.[8] In 1961, after Johnson resigned from the Senate to become Vice President, Mansfield was unanimously elected the Democratic floor leader and thus Senate Majority Leader. Serving sixteen years, from 1961 until his retirement in 1977, Mansfield is the longest-serving Majority Leader in the history of the Senate.[7] The Washington Post compared Mansfield's behavior as Majority Leader to Johnson's by saying, "Instead of Johnson's browbeating tactics, Mansfield led by setting an example of humility and accommodation."[6]

|

|

An early supporter of Ngo Dinh Diem, Mansfield had a change of heart on the Vietnam War after a visit to Vietnam in 1962. He reported to John F. Kennedy on December 2, 1962, that US money given to Diem's government was being squandered and that the US should avoid further involvement in Vietnam. He was thus the first American official to comment adversely on the war's progress.[11]

On September 25, 1963, Mansfield introduced Kennedy during a joint appearance with him at the Yellowstone County Fairgrounds, Kennedy expressing his appreciation afterward and adding, "I know that those of you who live in Montana know something of his character and his high standard of public service, but I am not sure that you are completely aware of what a significant role he has played in the last 3 years in passing through the United States Senate measure after measure which strengthens this country at home and abroad."[12]

Mansfield delivered a eulogy on November 24, 1963 as President Kennedy's casket lay in state in the Capitol rotunda, saying, "He gave that we might give of ourselves, that we might give to one another until there would be no room, no room at all, for the bigotry, the hatred, prejudice, and the arrogance which converged in that moment of horror to strike him down."[13]

During the Johnson administration, Mansfield became a frequent and vocal critic of US involvement in the Vietnam War. In February 1965, he lobbied against escalating aerial bombardment of North Vietnam in the aftermath of Pleiku, arguing in a letter to the president that Operation Rolling Thunder would lead to a need for "vastly strengthened . . . American forces."[14]

In 1964, Mansfield, as Senate Majority Leader, filed a procedural motion to have the Civil Rights Act of 1964 discussed by the whole Senate rather than by the Judiciary Committee, which had killed similar legislation seven years earlier.[15]

He hailed the new Richard Nixon administration, especially the "Nixon Doctrine" announced at Guam in 1969 that the US would honor all treaty commitments, provide a nuclear umbrella for its allies, and supply weapons and technical assistance to countries where warranted without committing American forces to local conflicts.

In turn, Nixon turned to Mansfield for advice and as his liaison with the Senate on Vietnam. Nixon began a steady withdrawal of US troops shortly after taking office in January 1969, a policy supported by Mansfield. During his first term, Nixon reduced American forces by 95%, leaving only 24,200 in late 1972; the last ones left in March 1973.

During the economic crisis of 1971, Mansfield was not afraid to reach across the aisle to help the economy:

What we're in is not a Republican recession or a Democratic recession; both parties had much to do with bringing us where we are today. But we're facing a national situation which calls for the best which all of us can produce, because we know the results will be something which we will regret.[16]

Mansfield attended the November 17, 1976 meeting between President-elect Jimmy Carter and Democratic congressional leaders in which Carter sought out support for a proposal to have the president's power to reorganize the government reinstated with potential to be vetoed by Congress.[17]

Mansfield Amendments

Two controversial amendments by Mansfield limiting military funding of research were passed by Congress.

- The Mansfield Amendment of 1969, passed as part of the fiscal year 1970 Military Authorization Act (Public Law 91-121), prohibited military funding of research that lacked a direct or apparent relationship to specific military function. Through subsequent modification the Mansfield amendment moved the Department of Defense toward the support of more short-term applied research in universities."[18] The amendment affected the military, such as research funding by the Office of Naval Research (ONR).[19]

- The Mansfield Amendment of 1973 expressly limited appropriations for defense research through the Advanced Research Projects Agency, which is largely independent of the military, to projects with direct military application.[20]

An earlier Mansfield Amendment, offered in 1971, called for the number of US troops stationed in Europe to be halved. On May 19, 1971, however, the Senate defeated the resolution 61–36.

Mansfield sponsored SJ Resolution. 25 : The joint resolution to authorize and request the President to issue a proclamation designating the fourth Sunday in September,1973, as "National Next Door Neighbor Day", and in 1974 drafted legislation (S.J.RES.235) to honor the fourth Sunday in September of every subsequent year as "Good Neighbor Day".[21]

US ambassador to Japan

Mansfield retired from the Senate in 1976, and was appointed ambassador to Japan in April 1977 by Jimmy Carter,[22] a role he retained during the Reagan administration until 1988. While serving in Japan, Mansfield was highly respected. Mansfield was particularly renowned for describing the US-Japan relationship as the 'most important bilateral relationship in the world, bar none'.[23] Mansfield's successor in Japan, Michael Armacost, noted in his memoirs that, for Mansfield, the phrase was a 'mantra.' While in office, Mansfield also fostered relations between his home state of Montana and Japan. The state capital of Helena is the sister city to Kumamoto, on the island of Kyushu.[24]

Honors

The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library at the University of Montana, Missoula is named after him and his wife Maureen,[25] as was his request when informed of the honor. The library also contains the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Center, which is dedicated to Asian studies, and, like the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation, "advancing understanding and co-operation in U.S.-Asia relations." The Mike Mansfield Federal Building and United States Courthouse in Missoula was renamed in his honor in 2002.[26]

The Montana Democratic Party holds an annual Mansfield-Metcalf Dinner named partially in his honor.

In 1977, Mansfield received the U.S. Senator John Heinz Award for Greatest Public Service by an Elected or Appointed Official, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards.[27]

On January 19, 1989, Mansfield and Secretary of State George P. Shultz were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Ronald Reagan. In his speech, Reagan recognized Mansfield as someone who has "distinguished himself as a dedicated public servant and loyal American."[28] In 1990, he was given both the United States Military Academy, Sylvanus Thayer Award and Japan's Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers, Grand Cordon. This is Japan's highest honor for someone who is not a head of state.[29]

Death

Ambassador Mansfield died from congestive heart failure at the age of 98 on October 5, 2001.[29] He was survived by his daughter, Anne Fairclough Mansfield (1939?–2013),[30] and one granddaughter.

This gentleman went from snuffy to national and international prominence. And when he died in 2001, he was rightly buried in Arlington. If you want to visit his grave, don't look for him near the "Kennedy Eternal Flame", where so many politicians are laid to rest. Look for a small, common marker shared by the majority of our heroes. Look for the marker that says "Michael J. Mansfield, PVT. U.S. Marine Corps".

The burial plot of Pvt. and Mrs. Mansfield can be found in section 2, marker 49-69F of Arlington National Cemetery.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Michael Joseph Mansfield". Arlington Cemetery website.

- ↑ Warnock, Eleanor (2012-04-16). "End of an Era: Yamamoto, Top 'America Hand' Dies at 76". Wall Street Journal Japan Real Time. Retrieved 2012-04-18.

- ↑ "New York, New York City Births, 1846-1909," database, FamilySearch(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:2W8Z-L89 : accessed 15 May 2016), Michael Joseph Mansfield, 16 Mar 1903; citing Birth, Manhattan, New York, New York, United States, New York Municipal Archives, New York; FHL microfilm 1,983,861.

- 1 2 3 4 Charting a New Course: Mike Mansfield and U.S. Asian Policy. Rutland, VT: Charles E. Tuttle Company. 1978.

- 1 2 "Biography". The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation.

- 1 2 3 4 "125 Montana Newsmakers: Mike Mansfield". Great Falls Tribune.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Senate Leaders: Mike Mansfield, Quiet Leadership in Troubled Times". United States Senate.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "MANSFIELD, Michael Joseph (Mike), (1903–2001)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- 1 2 3 Wilson, Richard L. (2002). American Political Leaders. New York: Facts On File, Inc.

- ↑ Hachey, Thomas E. (Winter 1973–1974). "American Profiles on Capitol Hill: A Confidential Study for the British Foreign Office in 1943" (PDF). Wisconsin Magazine of History. 57 (2): 141–153. JSTOR 4634869. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-21.

- ↑ Glass, Andrew (December 2, 2013). "Mike Mansfield delivers assessment of Vietnam, Dec. 2, 1962". Politico. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- ↑ "382 - Remarks at the Yellowstone County Fairgrounds, Billings, Montana". American Presidency Project. September 25, 1963.

- ↑ "Eulogies to the Late President Kennedy". John F. Kennedy Fast Facts: Eulogies for President Kennedy. Retrieved 2015-01-07.

- ↑ Andrew J. Bacevich, Washington Rules: America's Path to Permanent War (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2010), 103.

- ↑ "Recess Reading: An Occasional Feature From The Judiciary Committee: The Civil Rights Act of 1964". United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary.

- ↑ "Economic Crisis: 1971 Year in Review, UPI.com" Archived 2009-05-05 at WebCite

- ↑ Weaver, Jr., Warren (November 18, 1976). "CARTER ASKS LEADERS OF CONGRESS TO HELP IN A REORGANIZATION". New York Times.

- ↑ "Federally funded research, decisions for a decade" (PDF). Office of Technology Assessment report. Hearing before the Subcommittee on Science of the Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, U.S. House of Representatives, One Hundred Second Congress, first session, March 20, 1991.by the United States. Congress. House. Committee on Science, Space, and Technology. Subcommittee on Science. Pub: Washington: U.S. G.P.O.: For sale by the Supt. of Docs., Congressional Sales Office, U.S. G.P.O., 1991. Chapter 2: The Value of Science and the Changing Research Economy, p. 61.

- ↑ "Reverberations from the Mansfield Amendment". Editorial by Herbert Laitinen, Anal. Chem., 42 (7), pp. 689, June 1970.

- ↑ "DARPA History". See "Mansfield Amendment of 1973" about halfway down the page.

- ↑ "Bill Summary & Status – US Library of Congress". See items 39 and 46.

- ↑ "United States Ambassador to Japan - Nomination of Michael J. Mansfield". American Presidency Project. April 7, 1977.

- ↑ "Testimony of Ambassador to Japan-designate John V. Roos before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, July 23, 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 13, 2009. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- ↑ "Mike Mansfield Quiet Leadership in Troubled Times". United States Senate. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ↑ "The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Library". Course Catalog 2006–2007. The University of Montana. Archived from the original on 2007-02-09. Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ↑ General Service Administration page on the Mike Mansfield Federal Building and United States Courthouse.

- ↑ National Winners | public service awards. Jefferson Awards.org. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ "Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom: January 19, 1989". The American Presidency Project. January 19, 1989. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- 1 2 Campi, Alicia. "The Role of Mike Mansfield in Consolidating Mongolia's International Status and in Establishing Diplomatic Relations with the United States," Archived 2011-07-27 at the Wayback Machine. The Mansfield Foundation. May 17, 2007.

- ↑ ANNE F. MANSFIELD Obituary: View ANNE MANSFIELD's Obituary by The Washington Post. Legacy.com (2013-04-24). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Keystonemarines.com Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine.

References

- Oberdorfer, Don (2003). Senator Mansfield: The Extraordinary Life of a Great American Statesman and Diplomat. ISBN 1-58834-166-6.

- Olson, Gregory A. (1995). 'Mansfield and Vietnam, a Study in Rhetorical Adaptation. Michigan State University Press. online

- Valeo, Francis R. (1999). Mike Mansfield, Majority Leader: A Different Kind of Senate, 1961–1976. New York: M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 0-7656-0450-7. online

- Whalen, Charles and Barbara (1985). The Longest Debate: A Legislative History of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Cabin John, Maryland: Seven Locks Press.

![]()

Other links

- "Michael Joseph Mansfield — Seaman, United States Navy — Private United States Marine Corps — United States Senator — United States Ambassador". Arlington National Cemetery.

- "The Honorable Michael J. Mansfield". Who's Who in Marine Corps History. History Division, United States Marine Corps. Archived from the original on 2007-04-29. Retrieved 2006-04-22.

- Thorne, Christopher (October 11, 2001). "Laid to Rest, A Tribute to Mike Mansfield". Associated Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mike Mansfield. |

- The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Foundation, U.S.-Asia relations

- The Maureen and Mike Mansfield Center at the University of Montana

- United States Congress. "Mike Mansfield (id: m000113)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- "Mike Mansfield". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- Legislative Summary: Statement by Senator Mike Mansfield, John F. Kennedy Library, 1964

- Remarks at the Presentation Ceremony for the Presidential Medal of Freedom – January 19, 1989

- Mike Mansfield Papers (University of Montana Archives)

- A film clip "Longines Chronoscope with Michael Mike Mansfield" is available at the Internet Archive

- Appearances on C-SPAN