Egyptian language

| Egyptian | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

r n km.t[1] | |||||||

| Region | Ancient Egypt | ||||||

| Era | evolved into Demotic by 600 BC and Coptic by 200 AD and was extinct by the 17th century or so, survives as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria | ||||||

|

Afro-Asiatic

| |||||||

| hieroglyphs, cursive hieroglyphs, hieratic, demotic and Coptic (later, occasionally Arabic script in government translations) | |||||||

| Language codes | |||||||

| ISO 639-2 |

egy (also cop for Coptic) | ||||||

| ISO 639-3 |

egy (also cop for Coptic) | ||||||

| Glottolog |

egyp1246[2] | ||||||

| Linguasphere |

11-AAA-a | ||||||

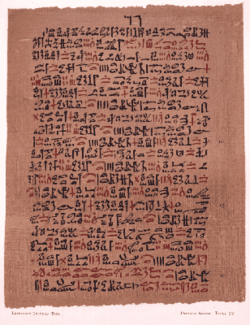

Ebers Papyrus detailing treatment of asthma | |||||||

The Egyptian language was spoken in ancient Egypt and was a branch of the Afro-Asiatic languages. Its attestation stretches over an extraordinarily long time, from the Old Egyptian stage (mid-3rd millennium BC, Old Kingdom of Egypt). Its earliest known complete written sentence has been dated to about 2690 BC, which makes it one of the oldest recorded languages known, along with Sumerian.[3]

Its classical form is known as Middle Egyptian, the vernacular of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt which remained the literary language of Egypt until the Roman period. The spoken language had evolved into Demotic by the time of Classical Antiquity, and finally into Coptic by the time of Christianisation. Spoken Coptic was almost extinct by the 17th century, but it remains in use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[4][5]

Classification

The Egyptian language belongs to the Afroasiatic language family.[6] Among the typological features of Egyptian that are typically Afroasiatic are its fusional morphology, nonconcatenative morphology, a series of emphatic consonants, a three-vowel system /a i u/, nominal feminine suffix *-at, nominal m-, adjectival *-ī and characteristic personal verbal affixes.[6] Of the other Afroasiatic branches, linguists have variously suggested that the Egyptian language shares its greatest affinities with Berber,[7] and Semitic.[8][9]

In Egyptian, the Proto-Afroasiatic voiced consonants */d z ð/ developed into pharyngeal ⟨ꜥ⟩ /ʕ/: ꜥr.t 'portal', Semitic dalt 'door'.[10] Afroasiatic */l/ merged with Egyptian ⟨n⟩, ⟨r⟩, ⟨ꜣ⟩, and ⟨j⟩ in the dialect on which the written language was based, but it was preserved in other Egyptian varieties.[10] Original */k g ḳ/ palatalise to ⟨ṯ j ḏ⟩ in some environments and are preserved as ⟨k g q⟩ in others.[10]

The Egyptian language has many biradical and perhaps monoradical roots, in contrast to the Semitic preference for triradical roots.[11] Egyptian is probably more conservative, and Semitic likely underwent later regularizations converting roots into the triradical pattern.[11]

Although Egyptian is the oldest Afroasiatic language documented in written form, its morphological repertoire is very different from that of the rest of the Afroasiatic, in general, and Semitic, in particular.[12] There are multiple possibilities: Egyptian had already undergone radical changes from Proto-Afroasiatic before it was recorded, the Afroasiatic family has so far been studied with an excessively Semito-centric approach, or, as G. W. Tsereteli suggests, Afroasiatic is an allogenetic rather than a genetic group of languages.[12]

History

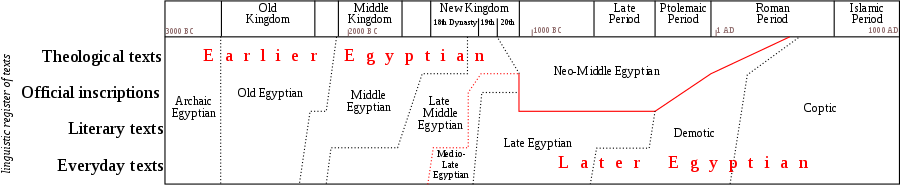

The Egyptian language is conventionally grouped into six major chronological divisions:[13]

- Archaic Egyptian (before 2600 BC), the reconstructed language of the Early Dynastic Period,

- Old Egyptian (c. 2600 – 2000 BC), the language of the Old Kingdom,

- Middle Egyptian (c. 2000 – 1350 BC), the language of the Middle Kingdom to early New Kingdom) and continuing on as a literary language into the 4th century,

- Late Egyptian (c. 1350 – 700 BC), Amarna period to Third Intermediate Period,

- Demotic (c. 700 BC – AD 400), the vernacular of the Late Period, Ptolemaic and early Roman Egypt,

- Coptic (after c. 200 AD), the vernacular at the time of Christianisation, and liturgical language of Egyptian Christianity.

Old, Middle, and Late Egyptian were all written using both the hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts. Demotic is the name of the script derived from hieratic beginning in the 7th century BC.

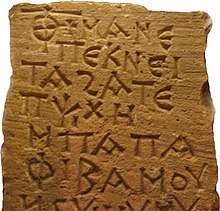

The Coptic alphabet was derived from the Greek alphabet, with adaptations for Egyptian phonology. It was first developed in the Ptolemaic period, and gradually replaced the Demotic script in about the 4th to 5th centuries CE.

Old Egyptian

The term "Archaic Egyptian" is sometimes reserved for the earliest use of hieroglyphs, from the late 4th through the early 3rd millennia BC. At the earliest stage, around 3300 BC;[14] hieroglyphs were not a fully developed writing system, being at a transitional stage of proto-writing; over the time leading up to the 27th century BC, grammatical features such as nisba formation can be seen to occur.[15][16]

Old Egyptian is dated from the oldest known complete sentence, including a finite verb, which has been found. Discovered in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen (dated c. 2690 BC), the seal impression reads:

| d(m)ḏ.n.f | tꜣwj n | zꜣ.f | nsw.t-bj.t(j) | pr-jb.sn(j) | ||||||||||||

| unite.PRF.3SG[17] | land.DUAL.PREP | son.3SG | sedge-bee | house-heart.3PL | ||||||||||||

| "He has united the Two Lands for his son, Dual King Peribsen."[18] | ||||||||||||||||

Extensive texts appear from about 2600 BC.[16] The Pyramid Texts are the largest body of literature written in this phase of the language. One of its distinguishing characteristics is the tripling of ideograms, phonograms, and determinatives to indicate the plural. Overall, it does not differ significantly from Middle Egyptian, the classical stage of the language, though it is based on a different dialect.

Middle Egyptian

Middle Egyptian was spoken for about 700 years, beginning around 2000 BC. Middle Egyptian is not descended directly from Old Egyptian, which was based on a different dialect.[19]

In writing, Middle Egyptian makes use of around 900 hieroglyphs.

As the classical variant of Egyptian, Middle Egyptian is the best-documented variety of the language, and has attracted the most attention by far from Egyptology. Whilst most Middle Egyptian is seen written on monuments by hieroglyphs, it was also written using a cursive variant, and the related hieratic.[20]

Middle Egyptian first became available to modern scholarship with the decipherment of hieroglyphs in the early 19th century. The first grammar of Middle Egyptian was published by Adolf Erman 1894, surpassed in 1927 by Alan Gardiner's work. Middle Egyptian has been well-understood since then, although certain points of the verbal inflection remained open to revision until the mid-20th century, notably due to the contributions of Hans Jakob Polotsky.[21]

The Middle Egyptian stage is taken to have ended around the 14th century BC, giving rise to Late Egyptian. This transition was taking place in the later period of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (known as the Amarna Period). Middle Egyptian was retained as a literary standard language, and in this usage survived until the Christianisation of Roman Egypt in the 4th century CE.

Late Egyptian

Late Egyptian, appearing around 1350 BC, is represented by a large body of religious and secular literature, comprising such examples as the Story of Wenamun, the love poems of the Chester–Beatty I papyrus, and the Instruction of Any. Instructions became a popular literary genre of the New Kingdom, which took the form of advice on proper behavior. Late Egyptian was also the language of New Kingdom administration.[22][23]

The Bible contains some words, terms and names that are thought by scholars to be Egyptian in origin. An example of this is Zaphnath-Paaneah, the Egyptian name given to Joseph.

Demotic and Coptic

Demotic is the name given to the Egyptian vernacular of the Late and Ptolemaic periods. It was written in the Demotic script, derived from a northern variety of hieratic writing.

Coptic is the name given to the stage of the language at the time of Christianisation. It survived into the medieval period, but by the 16th century was dwindling rapidly due to the persecution of Coptic Christians under the Mamluks. It probably survived in the Egyptian countryside as a spoken language for several centuries after that. Coptic survives as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria and the Coptic Catholic Church.

Dialects

Pre-Coptic Egyptian does not show great dialectal differences in the written language because of the centralised nature of Egyptian society.[24][25] However, differences must have existed in speech because a letter from c. 1200 BC complaints that the language of a correspondent is as unintelligible as the speech of a northern Egyptian to a southerner.[24][25]

Recently, some evidence of internal dialects has been found in pairs of similar words in Egyptian that, based on similarities with later dialects of Coptic, may be derived from northern and southern dialects of Egyptian.[26] Written Coptic has five major dialects, which differ mainly in graphic conventions, most notably the southern Saidic dialect, the main classical dialect, and the northern Bohairic dialect, currently used in Coptic Church services.[24][25]

Orthography

Most surviving texts in the Egyptian language are written on stone in hieroglyphs. The native name for Egyptian hieroglyphic writing is zẖꜣ n mdw-nṯr ("writing of the gods' words")[27]. However, in antiquity, most texts were written on perishable papyrus in hieratic and (later) demotic, which are now lost. There was also a form of cursive hieroglyphs, used for religious documents on papyrus, such as the Book of the Dead of the Twentieth Dynasty; it was simpler to write than the hieroglyphs in stone inscriptions, but it was not as cursive as hieratic and lacked the wide use of ligatures. Additionally, there was a variety of stone-cut hieratic, known as "lapidary hieratic". In the language's final stage of development, the Coptic alphabet replaced the older writing system.

Hieroglyphs are employed in two ways in Egyptian texts: as ideograms to represent the idea depicted by the pictures and, more commonly, as phonograms to represent their phonetic value.

As the phonetic realisation of Egyptian cannot be known with certainty, Egyptologists use a system of transliteration to denote each sound that could be represented by a uniliteral hieroglyph.[28]

Phonology

While the consonantal phonology of the Egyptian language may be reconstructed, the exact phonetics are unknown, and there are varying opinions on how to classify the individual phonemes. In addition, because Egyptian is recorded over a full 2000 years, the Archaic and Late stages being separated by the amount of time that separates Old Latin from Modern Italian, significant phonetic changes must have occurred during that lengthy time frame.

Phonologically, Egyptian contrasted labial, alveolar, palatal, velar, uvular, pharyngeal, and glottal consonants in a distribution rather similar to that of Arabic. Egyptian also contrasted voiceless and emphatic consonants, as with other Afroasiatic languages, but exactly how the emphatic consonants were realised is unknown. Early research had assumed that the opposition in stops was one of voicing, but it is now thought to be either one of tenuis and emphatic consonants, as in many Semitic languages, or one of aspirated and ejective consonants, as in many Cushitic languages.[29]

Since vowels were not written until Coptic, reconstructions of the Egyptian vowel system are much more uncertain and rely mainly on evidence from Coptic and records of Egyptian words, especially proper nouns, in other languages/writing systems. Also, scribal errors provide evidence of changes in pronunciation over time.

The actual pronunciations reconstructed by such means are used only by a few specialists in the language. For all other purposes, the Egyptological pronunciation is used, but it often bears little resemblance to what is known of how Egyptian was pronounced.

Consonants

The following consonants are reconstructed for Archaic (before 2600 BC) and Old Egyptian (2686–2181 BC), with IPA equivalents in square brackets if they differ from the usual transcription scheme:

| Labial | alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | ṯ [c] | k | q* | ʔ | ||

| voiced | b | d* | ḏ* [ɟ] | ɡ* | |||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | š [ʃ] | ẖ [ç] | ḫ [χ] | ḥ [ħ] | h | |

| voiced | z* | ꜣ (ȝ) [ʁ] | ꜥ (ʿ) [ʕ] | ||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | ||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

*Possibly unvoiced ejectives.

/l/ has no independent representation in the hieroglyphic orthography, and it is frequently written as if it were /n/ or /r/.[30] That is probably because the standard for written Egyptian is based on a dialect in which /l/ had merged with other sonorants.[10] Also, the rare cases of /ʔ/ occurring are not represented.[30] The phoneme /j/ is written as ⟨j⟩ in initial position (⟨jt⟩ = */ˈjaːtVj/ 'father') and immediately after a stressed vowel (⟨bjn⟩ = */ˈbaːjin/ 'bad') and as ⟨jj⟩ word-medially immediately before a stressed vowel (⟨ḫꜥjjk⟩ = */χaʕˈjak/ 'you will appear') and are unmarked word-finally (⟨jt⟩ = /ˈjaːtVj/ 'father').[30]

In Middle Egyptian (2055–1650 BC), a number of consonantal shifts take place. By the beginning of the Middle Kingdom period, /z/ and /s/ had merged, and the graphemes ⟨s⟩ and ⟨z⟩ are used interchangeably.[31] In addition, /j/ had become /ʔ/ word-initially in an unstressed syllable (⟨jwn⟩ /jaˈwin/ > */ʔaˈwin/ "colour") and after a stressed vowel (⟨ḥjpw⟩ */ˈħujpvw/ > /ˈħeʔp(vw)/ '[the god] Apis').[32]

In Late Egyptian (1069–700 BC), the phonemes d ḏ g gradually merge with their counterparts t ṯ k (⟨dbn⟩ */ˈdiːban/ > Akkadian transcription ti-ba-an 'dbn-weight'). Also, ṯ ḏ often become /t d/, but they are retained in many lexemes; ꜣ becomes /ʔ/; and /t r j w/ become /ʔ/ at the end of a stressed syllable and eventually null word-finally: ⟨pḏ.t⟩ */ˈpiːɟat/ > Akkadian transcription -pi-ta 'bow'.[33]

More changes occur in the 1st millennium BC and the first centuries AD, leading to Coptic (1st–17th centuries AD). In Sahidic ẖ ḫ ḥ had merged into ϣ š (most often from ḫ) and ϩ /h/ (most often ẖ ḥ).[34] Bohairic and Akhmimic are more conservative and have a velar fricative /x/ (ϧ in Bohairic, ⳉ in Akhmimic).[34] Pharyngeal *ꜥ had merged into glottal /ʔ/ after it had affected the quality of the surrounding vowels.[35] /ʔ/ is not indicated orthographically unless it follows a stressed vowel; then, it is marked by doubling the vowel letter (except in Bohairic): Akhmimic ⳉⲟⲟⲡ /xoʔp/, Sahidic and Lycopolitan ϣⲟⲟⲡ šoʔp, Bohairic ϣⲟⲡ šoʔp 'to be' < ḫpr.w */ˈχapraw/ 'has become'.[34][nb 1] The phoneme ⲃ /b/ was probably pronounced as a fricative [β], becoming ⲡ /p/ after a stressed vowel in syllables that had been closed in earlier Egyptian (compare ⲛⲟⲩⲃ < */ˈnaːbaw/ 'gold' and ⲧⲁⲡ < */dib/ 'horn').[34] The phonemes /d g z/ occur only in Greek loanwords, with rare exceptions triggered by a nearby /n/: ⲁⲛⲍⲏⲃⲉ/ⲁⲛⲥⲏⲃⲉ < ꜥ.t n.t sbꜣ.w 'school'.[34]

Earlier *d ḏ g q are preserved as ejective t' c' k' k' before vowels in Coptic.[36] Although the same graphemes are used for the pulmonic stops (⟨ⲧ ϫ ⲕ⟩), the existence of the former may be inferred because the stops ⟨ⲡ ⲧ ϫ ⲕ⟩ /p t c k/ are allophonically aspirated [pʰ tʰ cʰ kʰ] before stressed vowels and sonorant consonants.[36] In Bohairic, the allophones are written with the special graphemes ⟨ⲫ ⲑ ϭ ⲭ⟩, but other dialects did not mark aspiration: Sahidic ⲡⲣⲏ, Bohairic ⲫⲣⲏ 'the sun'.[36][nb 2]

Thus, Bohairic does not mark aspiration for reflexes of older *d ḏ g q: Sahidic and Bohairic ⲧⲁⲡ */dib/ 'horn'.[36] Also, the definite article ⲡ is unaspirated when the next word begins with a glottal stop: Bohairic ⲡ + ⲱⲡ > ⲡⲱⲡ 'the account'.[37]

The consonant system of Coptic is as follows:

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | ⲙ m |

ⲛ n |

||||

| Stop | voiceless | ⲡ (ⲫ) p (pʰ) |

ⲧ (ⲑ) t (tʰ) |

ϫ (ϭ) c (cʰ) |

ⲕ (ⲭ) k (kʰ) |

* ʔ |

| ejective | ⲧ tʼ |

ϫ cʼ |

ⲕ kʼ |

|||

| voiced | ⲇ d |

ⲅ ɡ |

||||

| Fricative | voiceless | ϥ f |

ⲥ s |

ϣ ʃ |

(ϧ, ⳉ) (x) |

ϩ ħ |

| voiced | ⲃ β |

ⲍ z |

||||

| Approximant | (ⲟ)ⲩ w |

ⲗ l |

(ⲉ)ⲓ j |

|||

| Trill | ⲣ r |

|||||

*Various orthographic representations; see above.

Vowels

Here is the vowel system reconstructed for earlier Egyptian:

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i iː | u uː |

| Open | a aː | |

Vowels are always short in unstressed syllables (⟨tpj⟩ = */taˈpij/ 'first') and long in open stressed syllables (⟨rmṯ⟩ = */ˈraːmac/ 'man'), they but can be either short or long in closed stressed syllables (⟨jnn⟩ = */jaˈnan/ 'we', ⟨mn⟩ = */maːn/ 'to stay').[39]

In the Late New Kingdom, after Ramses II, around 1200 BC, */ˈaː/ changes to */ˈoː/ (like the Canaanite shift), ⟨ḥrw⟩ '(the god) Horus' */ħaːra/ > */ħoːrə/ (Akkadian transcription: -ḫuru).[33][40] */uː/, therefore, changes to */eː/: ⟨šnj⟩ 'tree' */ʃuːn(?)j/ > */ʃeːnə/ (Akkadian transcription: -sini).[33]

In the Early New Kingdom, short stressed */ˈi/ changes to */ˈe/: ⟨mnj⟩ "Menes" */maˈnij/ > */maˈneʔ/ (Akkadian transcription: ma-né-e).[33] Later, probably 1000–800 BC, a short stressed */ˈu/ changes to */ˈe/: ⟨ḏꜥn.t⟩ "Tanis" */ˈɟuʕnat/ was borrowed into Hebrew as *ṣuʕn but would become transcribed as ⟨ṣe-e'-nu/ṣa-a'-nu⟩ during the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[41]

Unstressed vowels, especially after a stress, become */ə/: ⟨nfr⟩ 'good' */ˈnaːfir/ > */ˈnaːfə/ (Akkadian transcription -na-a-pa).[41] */iː/ changes to */eː/ next to /ʕ/ and /j/: ⟨wꜥw⟩ 'soldier' */wiːʕiw/ > */weːʕə/ (earlier Akkadian transcription: ú-i-ú, later: ú-e-eḫ).[41]

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | iː | ||

| Mid | e eː | ə | oː |

| Open | a | ||

In Sahidic and Bohairic Coptic, Late Egyptian stressed */ˈa/ becomes */ˈo/ and */ˈe/ becomes /ˈa/, but are unchanged in the other dialects: ⟨sn⟩ */san/ 'brother' > Sahaidic and Bohairic ⟨son⟩, Akhminic, Lycopolitan and Fayyumic ⟨san⟩; ⟨rn⟩ 'name' */rin/ > */ren/ > Sahaidic and Bohairic ⟨ran⟩, Akhminic, Lycopolitan and Fayyumic ⟨ren⟩.[35] However, Sahaidic and Bohairic preserve */ˈa/, and Fayyumic renders it as ⟨e⟩ in the presence of guttural fricatives: ⟨ḏbꜥ⟩ 'ten thousand' */ˈbaʕ/ > Sahaidic, Akhmimic and Lycopolitan ⟨tba⟩, Bohairic ⟨tʰba⟩, Fayyumic ⟨tbe⟩.[42] In Akhmimic and Lycopolitan, */ˈa/ becomes /ˈo/ before etymological /ʕ, ʔ/: ⟨jtrw⟩ 'river' */ˈjatraw/ > */jaʔr(ə)/ > Sahaidic ⟨eioor(e)⟩, Bohairic ⟨ior⟩, Akhminic ⟨ioore, iôôre⟩, Fayyumic ⟨iaal, iaar⟩.[42] Similarly, the diphthongs */ˈaj/, */ˈaw/, which normally have reflexes /ˈoj/, /ˈow/ in Sahidic and are preserved in other dialects, are in Bohairic ⟨ôi⟩ (in non-final position) and ⟨ôou⟩ respectively: "to me, to them" Sahidic ⟨eroi, eroou⟩, Akhminic and Lycopolitan ⟨arai, arau⟩, Fayyumic ⟨elai, elau⟩, Bohairic ⟨eroi, erôou⟩.[42] Sahidic and Bohairic preserve */ˈe/ before /ʔ/ (etymological or from lenited /t r j/ or tonic-syllable coda /w/),: Sahidic and Bohairic ⟨ne⟩ /neʔ/ 'to you (fem.)' < */ˈnet/ < */ˈnic/.[42] */e/ may also have different reflexes before sonants, near sibilants and in diphthongs.[42]

Old */aː/ surfaces as /uː/ after nasals and occasionally other consonants: ⟨nṯr⟩ 'god' */ˈnaːcar/ > /ˈnuːte/ ⟨noute⟩ [43] /uː/ has acquired phonemic status, as is evidenced by minimal pairs like 'to approach' ⟨hôn⟩ /hoːn/ < */ˈçaːnan/ ẖnn vs. 'inside' ⟨houn⟩ /huːn/ < */ˈçaːnaw/ ẖnw.[44] An etymological */uː/ > */eː/ often surfaces as /iː/ next to /r/ and after etymological pharyngeals: ⟨hir⟩ < */χuːr/ 'street' (Semitic loan).[44]

Most Coptic dialects have two phonemic vowels in unstressed position.[44] Unstressed vowels generally became /ə/, written as ⟨e⟩ or null (⟨i⟩ in Bohairic and Fayyumic word-finally), but pretonic unstressed /a/ occurs as a reflex of earlier unstressed */e/ near an etymological pharyngeal, velar or sonorant ('to become many' ⟨ašai⟩ < ꜥšꜣ */ʕiˈʃiʀ/) or an unstressed */a/.[44] Pretonic [i] is underlyingly /əj/: Sahidic 'ibis' ⟨hibôi⟩ < h(j)bj.w */hijˈbaːj?w/.[44]

Thus, the following is the Sahidic vowel system c. 400 CE:

| Stressed | Unstressed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Back | Central | |

| Close | iː | uː | |

| Mid | e eː | o oː | ə |

| Open | a | ||

Phonotactics

Earlier Egyptian has the syllable structure CV(:)(C) in which V is long in open stressed syllables and short elsewhere.[39] In addition, CV:C or CVCC can occur in word-final, stressed position.[39] However, CV:C occurs only in the infinitive of biconsonantal verbal roots, CVCC only in some plurals.[39][41]

In later Egyptian, stressed CV:C, CVCC, and CV become much more common because of the loss of final dentals and glides.[41]

Stress

Earlier Egyptian stresses one of the last two syllables.[45] According to some scholars, that is a development from a stage in Proto-Egyptian in which the third-last syllable could be stressed, which was lost as open posttonic syllables lost their vowels: */ˈχupiraw/ > */ˈχupraw/ 'transformation'.[45]

Egyptological pronunciation

As a convention, Egyptologists make use of an "Egyptological pronunciation" in English: the consonants are given fixed values, and vowels are inserted according to essentially arbitrary rules. Two consonants, alef and ayin, are generally pronounced /ɑː/. Yodh is pronounced /iː/, w /uː/. Between other consonants, /ɛ/ is then inserted. Thus, for example, the name of an Egyptian king is most accurately transliterated as Rꜥ-ms-sw and transcribed as "Rɑmɛssu"; it means "Ra has Fashioned (literally, "Borne") Him".

In transcription, ⟨a⟩, ⟨i⟩, and ⟨u⟩ all represent consonants; for example, the name Tutankhamun (1341–1323 BC) was written in Egyptian as twt-ꜥnḫ-ı͗mn.

Experts have assigned generic sounds to these values as a matter of convenience, which is an artificial pronunciation and should not be mistaken for how Egyptian was ever pronounced at any time.

For example, the name twt-ꜥnḫ-ı͗mn is conventionally pronounced /tuːtənˈkɑːmən/ in English, but, in his lifetime, it was likely to be pronounced something like *[taˈwaːt ˈʕaːnxu ʔaˈmaːn].[46][47][48][49][50][51][52][40]

Morphology

Egyptian is fairly typical for an Afroasiatic language in that at the heart of its vocabulary is most commonly a root of three consonants, but there are sometimes only two consonants in the root: rꜥ(w) [riːʕa] "sun" (the [ʕ] is thought to have been something like a voiced pharyngeal fricative). Larger roots are also common and can have up to five consonants: sḫdḫd "be upside-down".

Vowels and other consonants are added to the root to derive different meanings, as Arabic, Hebrew, and other Afroasiatic languages still do. However, because vowels and sometimes glides are not written in any Egyptian script except Coptic, it can be difficult to reconstruct the actual forms of words. Thus, orthographic ⟨stp⟩ "to choose", for example, can represent the stative (whose endings can be left unexpressed), the imperfective forms or even a verbal noun ("a choosing").

Nouns

Egyptian nouns can be masculine or feminine (the latter is indicated, as with other Afroasiatic languages, by adding a -t) and singular or plural (-w / -wt), or dual (-wy / -ty).

Articles, both definite and indefinite, do not occur until Late Egyptian but are used widely thereafter.

Pronouns

Egyptian has three different types of personal pronouns: suffix, enclitic (called "dependent" by Egyptologists) and independent pronouns. There are also a number of verbal endings added to the infinitive to form the stative and are regarded by some linguists[53] as a "fourth" set of personal pronouns. They bear close resemblance to their Semitic counterparts. The three main sets of personal pronouns are as follows:

| Suffix | Dependent | Independent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | -ı͗ | wı͗ | ı͗nk |

| 2nd sg. m. | -k | tw | ntk |

| 2nd sg. f. | -t | tn | ntt |

| 3rd sg. m. | -f | sw | ntf |

| 3rd sg. f. | -s | sy | nts |

| 1st pl. | -n | n | ı͗nn |

| 2nd pl. | -tn | tn | nttn |

| 3rd pl. | -sn | sn | ntsn |

Demonstrative pronouns have separate masculine and feminine singular forms and common plural forms for both genders:

| Mas. | Fem. | Plu. | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| pn | tn | nn | this, that, these, those |

| pf | tf | nf | that, those |

| pw | tw | nw | this, that, these, those (archaic) |

| pꜣ | tꜣ | nꜣ | this, that, these, those (colloquial [earlier] & Late Egyptian) |

Finally are interrogative pronouns.They bear a close resemblance to their Semitic and Berber counterparts:

| Pronoun | Meaning | Dependency |

|---|---|---|

| mı͗ | who / what | Dependent |

| ptr | who / what | Independent |

| iḫ | what | Dependent |

| ı͗šst | what | Independent |

| zı͗ | which | Independent & Dependent |

Verbs

Egyptian verbs have finite and non-finite forms.

Finite verbs convey person, tense/aspect, mood and voice. Each is indicated by a set of affixal morphemes attached to the verb: the basic conjugation is sḏm.f "he hears".

Non-finite verbs occur without a subject and are the infinitive, the participles and the negative infinitive, which Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs calls "negatival complement". There are two main tenses/aspects in Egyptian: past and temporally-unmarked imperfective and aorist forms. The latter are determined from their syntactic context.

Adjectives

Adjectives agree in gender and number with the nouns they modify: s nfr "(the) good man" and st nfrt "(the) good woman".

Attributive adjectives in phrases are after the nouns they modify: "(the) great god" (nṯr ꜥꜣ).

However, when they are used independently as a predicate in an adjectival phrase, as "(the) god (is) great" (ꜥꜣ nṯr) (literally, "great (is the) god"), adjectives precede the nouns they modify.

Prepositions

Egyptian uses prepositions which, like in English and many other Indo-European languages, always come before the noun, never after.

| m | "in, as, with, from" |

| n | "to, for" |

| r | "to, at" |

| ı͗n | "by" |

| ḥnꜥ | "with" |

| mı͗ | "like" |

| ḥr | "on, upon" |

| ḥꜣ | "behind, around" |

| ẖr | "under" |

| tp | "atop" |

| ḏr | "since" |

Adverbs

Adverbs, in Egyptian, are at the end of a sentence: in zı͗.n nṯr ı͗m "the god went there", "there" (ı͗m) is the adverb. Here are some other common Egyptian adverbs:

| ꜥꜣ | "here" |

| ṯnı͗ | "where" |

| zy-nw | "when" (lit. "what moment") |

| mı͗-ı͗ḫ | "how" (lit. "like-what") |

| r-mı͗ | "why" (lit. "for what") |

| ḫnt | "before" |

Syntax

Old Egyptian, Classical Egyptian and Middle Egyptian have verb-subject-object as the basic word order. However, that changed in the later stages of the language, including Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.

The equivalent to "the man opens the door" would be a sentence that would correspond, in the language's earlier stages, to "opens the man the door" (wn s ꜥꜣ). The so-called status constructus combines two or more nouns to express the genitive, like in Semitic and Berber languages.

The early stages of Egyptian have no articles, but the later forms use pꜣ, tꜣ and nꜣ. Like in other Afroasiatic languages, Egyptian uses two grammatical genders: masculine and feminine. It also uses three grammatical numbers: singular, dual and plural. However, later Egyptian has a tendency to lose the dual as a productive form.

Legacy

| Look up Category:English terms derived from Egyptian in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

The Egyptian language survived into the early modern period in the form of the Coptic language. The Copts were heavily persecuted under Islamic rule, especially under the Mamluk Sultanate, and Coptic survived past the 16th century only as an isolated vernacular.

However, in antiquity, Egyptian exerted some influence on Classical Greek, so that a number of Egyptian loanwords into Greek survive into modern usage. Examples include ebony (Egyptian 𓍁𓈖𓏭𓆱 hbny, via Greek and then Latin), ivory (Egyptian ꜣbw, literally 'ivory, elephant'), natron (via Greek), lily (via Greek, from Coptic hlēri), ibis (via Greek, from Egyptian hbj), oasis (via Greek, from Demotic wḥj), perhaps barge (possibly from Greek baris "Egyptian boat", from Coptic bari "small boat"), and possibly cat;[54] and of course a number of terms and proper names directly associated with Ancient Egypt, such as pharaoh (Egyptian 𓉐𓉻 pr-ꜥꜣ, literally "great house", transmitted via Hebrew and Greek). The name Egypt itself is etymologically identical to that of the Copts, ultimately from the Late Egyptian name of Memphis, Hikuptah, a continuation of Middle Egyptian ḥwt-kȝ-ptḥ "home of the ka (soul) of Ptah".[55]

A number of words in Biblical Hebrew are also traced to Egyptian;[56] apart from "Pharaoh", most of these have not entered Greek, Latin or English usage.[57]

See also

Notes

- ↑ There is evidence of Bohairic having a phonemic glottal stop: Loprieno (1995:44).

- ↑ In other dialects, the graphemes are used only for clusters of a stop followed by /h/ and were not used for aspirates: see Loprieno (1995:248).

References

- ↑ Erman, Adolf; Grapow, Hermann (1926-1961). Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, ISBN 3050022647

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Egyptian (Ancient)". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Allen, James Peter (2013). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-107-03246-0.

- ↑ The language may have survived in isolated pockets in Upper Egypt as late as the 19th century, according to James Edward Quibell, "When did Coptic become extinct?" in Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, 39 (1901), p. 87.

- ↑ "Coptic language's last survivors". Daily Star Egypt, December 10, 2005 (archived)

- 1 2 Loprieno (1995:1)

- ↑ Frajzyngier, Zygmunt; Shay, Erin (2012-05-31). The Afroasiatic Languages. Cambridge University Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780521865333.

- ↑ Loprieno (1995:5)

- ↑ Allan, Keith (2013). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Linguistics. OUP Oxford. p. 264. ISBN 0199585849. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Loprieno (1995:31)

- 1 2 Loprieno (1995:52)

- 1 2 Loprieno (1995:51)

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn A.; Steven Blake Shubert (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 325. ISBN 0-415-18589-0.

- ↑ Richard Mattessich, "Oldest writings, and inventory tags of Egypt", Accounting Historians Journal, 2002, Vol. 29, no. 1, 195–208.

- ↑ Richard Mattessich (2002). "The oldest writings, and inventory tags of Egypt". Accounting Historians Journal. 29 (1): 195–208. JSTOR 40698264.

- 1 2 Allen, James P. (2003). The Ancient Egyptian Language. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-107-66467-8.

- ↑ Werning, Daniel A. (2008) “Aspect vs. Relative Tense, and the Typological Classification of the Ancient Egyptian sḏm.n⸗f” in Lingua Aegyptia 16, p. 289.

- ↑ Allen, James Peter (2013). The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-107-03246-0. citing Jochem Kahl, Markus Bretschneider, Frühägyptisches Wörterbuch, Part 1 (2002), p. 229.

- ↑ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/265009/hieroglyph

- ↑ http://archive.archaeology.org/9903/newsbriefs/egypt.html

- ↑ H. J. Polotsky, Études de syntaxe copte Société d'Archéologie Copte, Le Caire (1944); H. J. Polotsky, Egyptian Tenses, Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Vol. II, No. 5 (1965).

- ↑ Loprieno, op.cit., p.7

- ↑ Meyers, op.cit., p. 209

- 1 2 3 Allen (2000:2)

- 1 2 3 Loprieno (1995:8)

- ↑ Satzinger (2008:10)

- ↑ Schiffman, Lawrence H. (2003-01-01). Semitic Papyrology in Context: A Climate of Creativity : Papers from a New York University Conference Marking the Retirement of Baruch A. Levine. BRILL. ISBN 9004128859.

- ↑ Allen (2000:13)

- ↑ See Egyptian Phonology, by Carsten Peust, for a review of the history of thinking on the subject; his reconstructions of words are nonstandard.

- 1 2 3 4 Loprieno (1995:33)

- ↑ Loprieno (1995:34)

- 1 2 Loprieno (1995:35)

- 1 2 3 4 Loprieno (1995:38)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Loprieno (1995:41)

- 1 2 3 Loprieno (1995:46)

- 1 2 3 4 Loprieno (1995:42)

- ↑ Loprieno (1995:43)

- ↑ Loprieno (1995:40–42)

- 1 2 3 4 Loprieno (1995:36)

- 1 2 Allen, J. The Ancient Egyptian Language: An Historical Study, Cambridge (2013)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Loprieno (1995:39)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Loprieno (1995:47)

- ↑ Loprieno (1995:47–48)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Loprieno (1995:48)

- 1 2 Loprieno (1995:37)

- ↑ Vycichl, W. Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Copte, Leuven 1983, pp. 10, 224, 250

- ↑ Vycichl, W. La vocalisation de la langue égyptienne, IFAO, Le Caire (Cairo) (1990), p. 215

- ↑ Fecht, G. Wortakzent und Silbenstruktur - Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der ägyptischen Sprache, Glückstadt-Hamburg-New York (1960), §§ 112 A. 194, 254 A. 395

- ↑ Osing, J. Die Nominalbildung des Ägyptischen. Deutsches archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo (1976)

- ↑ Schenkel, W. "Zur Rekonstruktion deverbalen Nominalbildung des Ägyptischen", Harrasowitz, Wiesbaden. 1983, pp. 212, 214,247

- ↑ Vergote, Jozef. "Grammaire Copte". Louvain : Peters, 1973-1983

- ↑ Loprieno, A. Ancient Egyptian - A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press (1995)

- ↑ Loprieno 1995, p. 65

- ↑ Often assumed to represent the precursor of Coptic ϣⲁⲩ (šau "tomcat") suffixed with feminine -t, but some authorities dispute this, e.g. John Huehnergard, "Qitta: Arabic Cats", in: Classical Arabic Humanities in Their Own Terms (2007).

- ↑ Hoffmeier, James K (1 October 2007). "Rameses of the Exodus narratives is the 13th B.C. Royal Ramesside Residence". Trinity Journal: 1.

- ↑ Benjamin J. Noonan, Egyptian Loanwords as Evidence for the Authenticity of the Exodus and Wilderness Traditions

- ↑ A possible exception is behemoth (of uncertain etymology, possibly from a presumed *pꜣ-jḥ-mw "hippopotamus", but it may also be a native Semitic word).

Bibliography

- Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge University press. ISBN 0-521-65312-6.

- Callender, John B. (1975). Middle Egyptian. Undena Publications. ISBN 0-89003-006-5.

- Loprieno, Antonio (1995). Ancient Egyptian: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge University press. ISBN 0-521-44384-9.

- Satzinger, Helmut (2008). "What happened to the voiced consonants of Egyptian?" (PDF). 2. Acts of the X International Congress of Egyptologists. pp. 1537–1546.

Literature

Overviews

- Loprieno, Antonio, Ancient Egyptian: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-521-44384-9 (hbk) ISBN 0-521-44849-2 (pbk)

- Peust, Carsten, Egyptian phonology : an introduction to the phonology of a dead language, Peust & Gutschmidt, 1999. ISBN 3-933043-02-6 PDF

- Vycichl, Werner, La vocalisation de la langue égyptienne, IFAO, Le Caire (Cairo), 1990. ISBN 9782-7247-0096-1

- Vergote, Jozef, "Problèmes de la «Nominalbildung» en égyptien", Chronique d'Égypte 51 (1976), 261-285

Grammars

- Allen, James P., Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs, first edition, Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-65312-6 (hbk) ISBN 0-521-77483-7 (pbk)

- Borghouts, Joris F., Egyptian: An Introduction to the Writing and Language of the Middle Kingdom (2 vols.), Peeters, 2010. ISBN 978-9-042-92294-5 (pbk, 2 vol. set)

- Collier, Mark, and Manley, Bill, How to Read Egyptian Hieroglyphs : A Step-by-Step Guide to Teach Yourself, British Museum Press ( ISBN 0-7141-1910-5) and University of California Press ( ISBN 0-520-21597-4), both in 1998.

- Gardiner, Sir Alan H., Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Griffith Institute, Oxford, 3rd ed. 1957. ISBN 0-900416-35-1

- Hoch, James E., Middle Egyptian Grammar, Benben Publications, Mississauga, 1997. ISBN 0-920168-12-4

- Selden, Daniel L., Hieroglyphic Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Literature of the Middle Kingdom, Univ. of California Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0-520-27546-1 (hbk)

Dictionaries

- Adolf Erman, Hermann Grapow: Das Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH, Berlin, 1992. ISBN 978-3-05-002264-2 (paperback), ISBN 978-3-05-002266-6 (reference vols 1-5)

- Raymond O. Faulkner: A Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Griffith Institute, Oxford, 1962. ISBN 0-900416-32-7 (hardback)

- Leonard H. Lesko: A Dictionary of Late Egyptian, 2nd ed., 2 Vols., B.C. Scribe Publications, Providence, 2002 et 2004. ISBN 0-930548-14-0 (vol.1), ISBN 0-930548-15-9 (vol. 2).

- Shennum, *, English-Egyptian Index of Faulkner's Concise Dictionary of Middle Egyptian, Undena Publications, 1977. ISBN 0-89003-054-5

- Yvonne Bonnamy and Ashraf-Alexandre Sadek: Dictionnaire des hiéroglyphes: Hiéroglyphes-Français, Actes Sud, Arles, 2010. ISBN 978-2-7427-8922-1

- Werner Vycichl: Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Copte, Peeters, Leuven, 1984. ISBN 2-8017-0197-1

Online dictionaries

- The Beinlich Wordlist, an online searchable dictionary of ancient Egyptian words (translations are in German)

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae, an online service available from October 2004 which is associated with various German Egyptological projects, including the monumental Altägyptisches Wörterbuch of the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (Brandenburg Academy of Sciences, Berlin, Germany).

- Mark Vygus Dictionary 2018, a searchable dictionary of ancient Egyptian words, arranged by glyph

Important Note: the old grammars and dictionaries of E. A. Wallis Budge have long been considered obsolete by Egyptologists, even though these books are still available for purchase.

More book information is available at Glyphs and Grammars

External links

| Egyptian language repository of Wikisource, the free library |

- Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae: Dictionary of the Egyptian language

- The Pronunciation of Ancient Egyptian by Kelley L. Ross

- The Egyptian connection: Egyptian and the Semitic languages by Helmut Satzinger

- Ancient Egyptian Language Discussion List

- Dictionnaire Étymologique de la Langue Copte by Werner Vycichl

- Site containing direct translations from English to Egyptian

- Ancient Egyptian in the wiki Glossing Ancient Languages (recommendations for the Interlinear Morphemic Glossing of Ancient Egyptian texts)