Art of ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptian art is the painting, sculpture, architecture and other arts produced by the civilization of ancient Egypt in the lower Nile Valley from about 3000 BC to 30 AD. Ancient Egyptian art reached a high level in painting and sculpture, and was both highly stylized and symbolic. It was famously conservative, and Egyptian styles changed remarkably little over more than three thousand years. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments and now there is an emphasis on life after death and the preservation of knowledge of the past. The wall art was never meant to be seen by people other than the afterlife for when they needed them.

Ancient Egyptian art included paintings, sculpture in wood (now rarely surviving), stone and ceramics, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewellery, ivories, and other art media. It displays an extraordinarily vivid representation of the ancient Egyptian's socioeconomic status and belief systems.

Overview

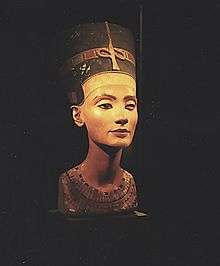

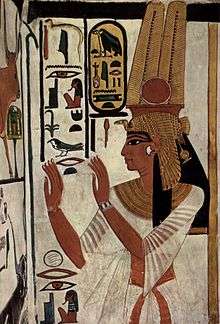

Egyptian art is famous for its distinctive figure convention, used for the main figures in both relief and painting, with parted legs (where not seated) and head shown as seen from the side, but the torso seen as from the front, and a standard set of proportions making up the figure, using 18 "fists" to go from the ground to the hair-line on the forehead.[1] This appears as early as the Narmer Palette from Dynasty I, but there as elsewhere the convention is not used for minor figures shown engaged in some activity, such as the captives and corpses.[2] Other conventions make statues of males darker than females ones. Very conventionalized portrait statues appear from as early as Dynasty II, before 2,780 BC,[3] and with the exception of the art of the Amarna period of Ahkenaten,[4] and some other periods such as Dynasty XII, the idealized features of rulers, like other Egyptian artistic conventions, changed little until after the Greek conquest.[5]

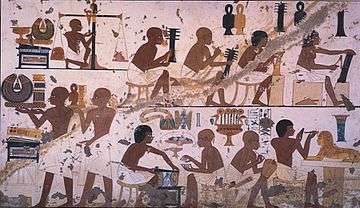

Egyptian art uses hierarchical proportion, where the size of figures indicates their relative importance. The gods or the divine pharaoh are usually larger than other figures and the figures of high officials or the tomb owner are usually smaller, and at the smallest scale any servants and entertainers, animals, trees, and architectural details.[6]

Symbolism can be observed throughout Egyptian art and played an important role in establishing a sense of order. The pharaoh's regalia, for example, represented his power to maintain order. Animals were also highly symbolic figures in Egyptian art. Some colors were expressive.[7] Blue, for example, symbolized fertility, birth, and the life-giving waters of the Nile.[8] The use of black for royal figures similarly expressed the fertility of the Nile from which Egypt was born.[7] Gold indicated divinity due to its unnatural appearance and association with precious materials.[7] Furthermore, gold was regarded by the ancient Egyptians as "the flesh of the god."[9] Silver, referred to as "white gold" by the Egyptians, was likewise called "the bones of the god."[9]

Painting

Not all Egyptian reliefs were painted, and less prestigious works in tombs, temples and palaces were merely painted on a flat surface. Stone surfaces were prepared by whitewash, or if rough, a layer of coarse mud plaster, with a smoother gesso layer above; some finer limestones could take paint directly. Pigments were mostly mineral, chosen to withstand strong sunlight without fading. The binding medium used in painting remains unclear: egg tempera and various gums and resins have been suggested. It is clear that true fresco, painted into a thin layer of wet plaster, was not used. Instead the paint was applied to dried plaster, in what is called "fresco a secco" in Italian. After painting, a varnish or resin was usually applied as a protective coating, and many paintings with some exposure to the elements have survived remarkably well, although those on fully exposed walls rarely have.[10] Small objects including wooden statuettes were often painted using similar techniques.

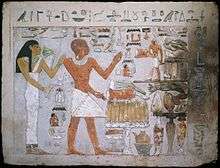

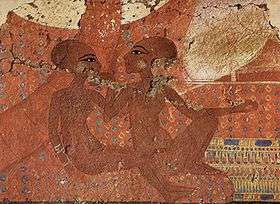

Many ancient Egyptian paintings have survived in tombs, and sometimes temples, due to Egypt's extremely dry climate. The paintings were often made with the intent of making a pleasant afterlife for the deceased. The themes included journey through the afterworld or protective deities introducing the deceased to the gods of the underworld (such as Osiris). Some tomb paintings show activities that the deceased were involved in when they were alive and wished to carry on doing for eternity.

In the New Kingdom and later, the Book of the Dead was buried with the entombed person. It was considered important for an introduction to the afterlife.

Egyptian paintings are painted in such a way to show a profile view and a side view of the animal or person at the same time. For example, the painting to the right shows the head from a profile view and the body from a frontal view. Their main colors were red, blue, green, gold, black and yellow.

Paintings showing scenes of hunting and fishing can have lively close-up landscape backgrounds of reeds and water, but in general Egyptian painting did not develop a sense of depth, and neither landscapes nor a sense of visual perspective are found, the figures rather varying in size with their importance rather than their location.

Sculpture

_and_queen.jpg)

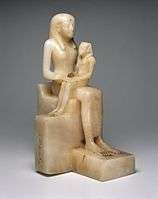

The monumental sculpture of ancient Egypt's temples and tombs is world-famous,[11] but refined and delicate small works exist in much greater numbers. The Egyptians used the technique of sunk relief, which is best viewed in sunlight for the outlines and forms to be emphasized by shadows. The distinctive pose of standing statues facing forward with one foot in front of the other was helpful for the balance and strength of the piece. The use of this singular pose was used early on in the history of Egyptian art and well into the Ptolemaic period, although seated statues were particularly common as well. Egyptian pharaohs were always regarded as gods, but other deities are much less common in large statues, except when they represent the pharaoh as another deity; however the other deities are frequently shown in paintings and reliefs. The famous row of four colossal statues outside the main temple at Abu Simbel each show Rameses II, a typical scheme, though here exceptionally large.[12] Most larger sculptures survive from Egyptian temples or tombs; massive statues were built to represent gods and pharaohs and their queens, usually for open areas in or outside temples. The very early colossal Great Sphinx of Giza was never repeated, but avenues lined with very large statues including sphinxes and other animals formed part of many temple complexes. The most sacred cult image of a god in a temple, usually held in the naos, was in the form of a relatively small boat or barque holding an image of the god, and apparently usually in precious metal – none have survived.

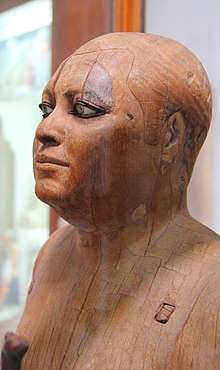

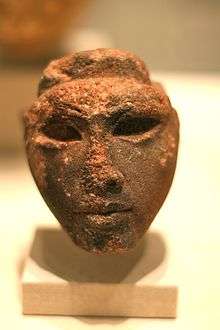

By Dynasty IV (2680–2565 BC) at the latest the idea of the Ka statue was firmly established. These were put in tombs as a resting place for the ka portion of the soul, and so we have a good number of less conventionalized statues of well-off administrators and their wives, many in wood as Egypt is one of the few places in the world where the climate allows wood to survive over millennia, and many block statues. The so-called reserve heads, plain hairless heads, are especially naturalistic, though the extent to which there was real portraiture in ancient Egypt is still debated.

Early tombs also contained small models of the slaves, animals, buildings and objects such as boats necessary for the deceased to continue his lifestyle in the afterworld, and later Ushabti figures.[13] However the great majority of wooden sculpture has been lost to decay, or probably used as fuel. Small figures of deities, or their animal personifications, are very common, and found in popular materials such as pottery. There were also large numbers of small carved objects, from figures of the gods to toys and carved utensils. Alabaster was often used for expensive versions of these; painted wood was the most common material, and normal for the small models of animals, slaves and possessions placed in tombs to provide for the afterlife.

Very strict conventions were followed while crafting statues and specific rules governed appearance of every Egyptian god. For example, the sky god (Horus) was essentially to be represented with a falcon's head, the god of funeral rites (Anubis) was to be always shown with a jackal's head. Artistic works were ranked according to their compliance with these conventions, and the conventions were followed so strictly that, over three thousand years, the appearance of statues changed very little. These conventions were intended to convey the timeless and non-aging quality of the figure's ka.

%2C_Egypt._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%2C_London.jpg)

A common relief in ancient Egyptian sculpture was the representation between men and women. Women were often represented in an idealistic form, young and pretty, and rarely shown in an older maturity. While men were shown in either one of two way; either in an idealistic manner or in more realistic depiction.[14] Sculptures of men often showed men that aged, since the regeneration of aging was as positive thing for them, women are shown as perpetually young.[15]

- Wooden tomb models, Dynastry XI; a high administrator counts his cattle.

_(Room_4).jpg) The Younger Memnon c. 1250 BC, British Museum

The Younger Memnon c. 1250 BC, British Museum Sunk relief of the crocodile god Sobek

Sunk relief of the crocodile god Sobek Osiris on a lapis lazuli pillar in the middle, flanked by Horus on the left, and Isis on the right, 22nd dynasty, Louvre

Osiris on a lapis lazuli pillar in the middle, flanked by Horus on the left, and Isis on the right, 22nd dynasty, Louvre The ka statue provided a physical place for the ka to manifest. Egyptian Museum, Cairo

The ka statue provided a physical place for the ka to manifest. Egyptian Museum, Cairo Block statue of Pa-Ankh-Ra, ship master, bearing a statue of Ptah. Late Period, ca. 650–633 BC, Cabinet des Médailles.

Block statue of Pa-Ankh-Ra, ship master, bearing a statue of Ptah. Late Period, ca. 650–633 BC, Cabinet des Médailles. A sculpted head of Amenhotep III

A sculpted head of Amenhotep III Queen Ankhnes-meryre II and her Son, Pepy II,c. 2200 BC. Brooklyn Museum

Queen Ankhnes-meryre II and her Son, Pepy II,c. 2200 BC. Brooklyn Museum

Faience, pottery, and glass

Egyptian faience, made from silica, found in form of quartz in sand, lime, and natron, produced relatively cheap and very attractive small objects in a variety of colours, and was used for a variety of types of objects including jewellery.[9] Ancient Egyptian glass goes back to very early Egyptian history, but was at first very much a luxury material. In later periods it became common, and highly decorated small jars for perfume and other liquids are often found as grave goods.

Ancient Egyptians used steatite (some varieties were called soapstone) and carved small pieces of vases, amulets, images of deities, of animals and several other objects. Ancient Egyptian artists also discovered the art of covering pottery with enamel. Covering by enamel was also applied to some stone works. The colour blue, first used in the very expensive imported stone lapis lazuli, was highly regarded by ancient Egypt, and the pigment Egyptian blue was widely used to colour a variety of materials.

Different types of pottery items were deposited in tombs of the dead. Some such pottery items represented interior parts of the body, like the lungs, the liver and smaller intestines, which were removed before embalming. A large number of smaller objects in enamel pottery were also deposited with the dead. It was customary to craft on the walls of the tombs cones of pottery, about six to ten inches tall, on which were engraved or impressed legends relating to the dead occupants of the tombs. These cones usually contained the names of the deceased, their titles, offices which they held, and some expressions appropriate to funeral purposes.

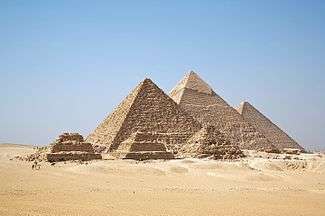

Architecture

Ancient Egyptian architects used sun-dried and kiln-baked bricks, fine sandstone, limestone and granite. Architects carefully planned all their work. The stones had to fit precisely together, since there was no mud or mortar. When creating the pyramids, ramps were used to allow workmen to move up as the height of the construction grew. When the top of the structure was completed, the artists decorated from the top down, removing ramp sand as they went down. Exterior walls of structures like the pyramids contained only a few small openings. Hieroglyphic and pictorial carvings in brilliant colors were abundantly used to decorate Egyptian structures, including many motifs, like the scarab, sacred beetle, the solar disk, and the vulture. They described the changes the Pharaoh would go through to become a god.[16]

Amarna period

The Amarna period and the years before the pharaoh Akhenaten moved the capital there in the late Eighteenth Dynasty form the most drastic interruption to the continuity of style in the Old and New Kingdoms. Amarna art is characterized by a sense of movement and activity in images, with figures having raised heads, many figures overlapping and many scenes full and crowded. As the new religion was a monotheistic worship of the sun, sacrifices and worship were apparently conducted in open courtyards, and sunk relief decoration was widely used in these.

The human body is portrayed differently in the Amarna style than Egyptian art on the whole. For instance, many depictions of Akhenaten's body give him distinctly feminine qualities, such as large hips, prominent breasts, and a larger stomach and thighs. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which shows men with perfectly chiseled bodies. Faces are still shown exclusively in profile.

Not many buildings from this period have survived the ravages of later kings, partially as they were constructed out of standard size blocks, known as Talatat, which were very easy to remove and reuse. Temples in Amarna, following the trend, did not follow traditional Egyptian customs and were open, without ceilings, and had no closing doors. In the generation after Akhenaten's death, artists reverted to their old styles. There were still traces of this period's style in later art, but in most respects Egyptian art, like Egyptian religion, resumed its usual characteristics after the death of Akhenaten as though the period had never happened. Amarna itself was abandoned and considerable trouble was gone to in defacing monuments from the reign, including dis-assembling buildings and reusing the blocks with their decoration facing inwards, as has recently been discovered in one later building.

The Late Period

_-_Egypt-6A-019.jpg)

In 525 B.C., the political state of Egypt was taken over by the Persians, almost a century and a half into Egypt's Late Period. By 404 B.C., the Persians were expelled from Egypt starting a short period of independence. These 60 years of Egyptian rule consisted of an abundance of usurpers and short reigns. Again the Egyptians were plagued with Persians as they conquered Egypt again until 332 B.C.with the arrival of Alexander the Great. Sources state that were cheering when Alexander entered the capital since he drove out the immensely disliked Persians. The Late Period is marked with the death of Alexander the Great and the start of the Ptolemaic Dynasty.[14] Although this period marks political turbulence an immense change for Egypt, its art and culture continued to flourish.

Starting with the Thirtieth Dynasty, the fifth dynasty in the Late Period, and extending into the Ptolemaic era. These temples ranged from the Delta to the island of Philae.[14] While Egypt was outside fluencies through trade and conquered by foreign states, these temples were still in the traditional Egyptian style with very little Hellenistic influence.

Another relief originating from the Thirtieth Dynasty was the rounded modeling of the body and limbs.[14] This rounded modeling refers to giving the subjects the sculpture or painting a more fleshy or heavy effect. For example, for women, their breast would swell and overlap the upper arm in painting. In more realistic portrayals, men would be fat or have wrinkled.

Another piece of art that increasingly common during was Horus stela.[14] Horus stela originates from the late New Kingdom and intermediate period but was increasingly common during the fourth century to the Ptolemaic era.These statues would often depict a young Horus holding snakes and standing on some kind of dangerous beast. The depiction of Horus comes from the Egyptian myth where a young Horus us saved from a scorpion bite resulting in him gaining power over all dangerous animals. These statues were used "to ward off attacks from harmful creatures, and to cure snake bites and scorpion stings."[14]

Ptolemaic period

Discoveries made since the end of the 19th century surrounding the (now submerged) ancient Egyptian city of Heracleum at Alexandria include a 4th-century BC, unusually sensual, detailed and feministic (as opposed to deified) depiction of Isis, marking a combination of Egyptian and Hellenistic forms beginning around the time of Egypt's conquest by Alexander the Great in 332-331 BC. However this was untypical of Ptolemaic sculpture, which generally avoided mixing Egyptian styles with the general Hellenistic style which was used in the court art of the Ptolemaic Dynasty,[17] while temples in the rest of the country continued using late versions of traditional Egyptian formulae.[18] Scholars have proposed an "Alexandrian style" in Hellenistic sculpture, but there is in fact little to connect it with Alexandria.[19]

Marble was extensively used in court art, although it all had to be imported, and use was made of various marble-saving techniques, such as making even heads up from a number of pieces, and using stucco for beards, the back of heads and hair.[20] In contrast to the art of other Hellenistic kingdoms, Ptolemaic royal portraits are generalized and idealized, with little concern for achieving an individual portrait, though thanks to coins some portrait sculpture can be identified as one of the 15 King Ptolemys.[21] Many later portraits have clearly had the face reworked to show a later king.[22] One Egyptian trait was to give much greater prominence to the queens than other successor dynasties to Alexander, with the royal couple often shown as a pair. This predated the 2nd century, a series of queens did indeed exercise real power.[23]

In the 2nd century, Egyptian temple sculptures did begin to reuse court models in their faces, and sculptures of priest often used a Hellenistic style to achieve individually distinctive portrait heads.[24] Many small statuettes were produced, with Alexander, as founder of the dynasty, a generalized "King Ptolemy", and a naked Aphrodite among the most common types. Pottery figurines included grotesques and fashionable ladies of the Tanagra figurine style.[18] Erotic groups featured absurdly large phalluses. Some fittings for wooden interiors include very delicately patterned polychrome falcons in faience.

| Ancient art history |

|---|

| Middle East |

| Asia |

| European prehistory |

| Classical art |

Notes

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 33

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 12–13 and note 17

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 21–24

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 170–178; 192–194

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 102–103; 133–134

- ↑ The Art of Ancient Egipt. A resource for educators (PDF). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 44. Retrieved July 7, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Historical Atlas of Ancient Egypt, Bill Manley (1996) p. 83

- ↑ "Color in Ancient Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-10-04.

- 1 2 3 Lacovara, Peter; Markowitz, Yvonne J. (2001). "Materials and Techniques in Egyptian Art". The Collector's Eye: Masterpieces of Egyptian Art from the Thalassic Collection, Ltd. Atlanta: Michael C. Carlos Museum. pp. XXIII–XXVIII.

- ↑ Grove

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 2

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 4–5; 208–209

- ↑ Smith, Stevenson, and Simpson, 89–90

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gay., Robins, (1997). The art of ancient Egypt. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674046609. OCLC 36817299.

- ↑ Sweeney, Deborah (2004). "Forever Young? The Representation of Older and Ageing Women in Ancient Egyptian Art". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 41: 67–84. doi:10.2307/20297188. JSTOR 20297188.

- ↑ Jenner, Jan (2008). Ancient Civilizations. Toronto: Scholastic.

- ↑ Smith, 206, 208-209

- 1 2 Smith, 210

- ↑ Smith, 205

- ↑ Smith, 206

- ↑ Smith, 207

- ↑ Smith, 209

- ↑ Smith, 208

- ↑ Smith, 208-209, 210

References

Further reading

Hill, Marsha (2007). Gifts for the gods: images from Egyptian temples. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392312.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ancient Egyptian art. |

- Ancient Egyptian Art – Aldokkan

- Senusret Collection: A well-annotated introduction to the arts of Egypt