Pyramid Texts

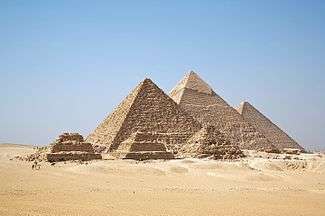

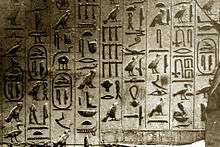

The Pyramid Texts are a collection of ancient Egyptian religious texts from the time of the Old Kingdom. Written in Old Egyptian, the pyramid texts were carved on the walls and sarcophagi of the pyramids at Saqqara during the 5th and 6th Dynasties of the Old Kingdom. The oldest of the texts have been dated to between ca. 2400–2300 BC.[1] Unlike the later Coffin Texts and Book of the Dead, the pyramid texts were reserved only for the pharaoh and were not illustrated.[2] Following the earlier Palermo Stone, the pyramid texts mark the next-oldest known mention of Osiris, who would become the most important deity associated with afterlife in the Ancient Egyptian religion.[3]

The use and occurrence of pyramid texts changed between the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms of Ancient Egypt. During the Old Kingdom (2886 B.C.- 2181 B.C.), pyramid texts could be found in the pyramids of kings as well as a three queens named Wedjebten, Neith, and Iput. During the Middle Kingdom (2055 B.C.- 1650 B.C.) pyramid texts were not written in the pyramids of the Pharaohs, but the traditions of the pyramid spells continued to be practiced. In the New Kingdom (1550 B.C.- 1070 B.C.) pyramid texts could now be found on tombs of officials.[4]

Purpose of pyramid texts

The spells, or "utterances", (short fragmented sentences) of the pyramid texts are primarily concerned with protecting the pharaoh's remains, reanimating his body after death, and helping him ascend to the heavens, which are the emphasis of the afterlife during the Old Kingdom. These utterances were meant to be chanted by those who were reciting them. They contained many verbs such as "fly" and "leap" depicting the actions taken by the Pharaohs to get to the afterlife.[5] The spells delineate all of the ways the pharaoh could travel, including the use of ramps, stairs, ladders, and most importantly flying. The spells could also be used to call the gods to help, even threatening them if they did not comply.[6] It was common for the pyramid texts to be written in the first person, but not uncommon for texts to be later changed to the third person. Often times this depended on who was reciting the texts and who they were recited for.[7] Many of the texts include accomplishments of the Pharaoh as well as the things they did for the Egyptian people during the time of their rule. These texts were used to both guide the pharaohs to the afterlife, but also inform and assure the living that the soul made it to its final destination.[5]

Dates

The dates of the Pharaohs rule whose pyramids contain pyramid texts are as follows:

Unis: 2353-2323 B.C.

Teti: 2323-2291 B.C.

Pepi I: 2289-2255 B.C.

Merenre I: 2255-2246 B.C.

Pepi II: 2246-2152 B.C.[1]

Versions

The texts were first discovered in 1881 by Gaston Maspero, and translations were made by Kurt Heinrich Sethe (in German), Louis Speleers (in French), Raymond O. Faulkner, Samuel A. B. Mercer and James P. Allen (the latest translation in English). It was not until 1935 when the rest of the texts were discovered by Egyptologist Gustav Jaquier. [7]

The oldest version consists of 228 spells and comes from the Pyramid of Unas, who was the last king of the 5th Dynasty. Other texts were discovered in the pyramids of the 6th Dynasty kings Teti, Pepi I, Merenre, and Pepi II; they also occur in the pyramids of a number of 6th Dynasty queens, Ankhenespepy II, Neit, Iput II, Wedjebten, and Behenu. Pyramid Texts were also discovered on fragments of wood within the tomb of queen Meretites II.

Kurt Sethe's first edition of the pyramid texts contained 714 distinct spells; after this publication additional spells were discovered bringing the total to 759. No single collection uses all recorded spells.

Offerings and rituals

The various pyramid texts often contained writings of rituals and offerings to the gods. Examples of these rituals are the Opening of the mouth ceremony, offering rituals, and insignia ritual. Both monetary and prayer based offerings were made in the pyramids and were written in the pyramid texts in hopes of getting the pharaoh to a desirable afterlife.[8] Rituals such as the opening of the mouth and eye ceremony were very important for the Pharaoh in the afterlife. This ceremony involved the Kher-Heb (the chief lector priest) along with assistants opening the eyes and mouth of the dead while reciting prayers and spells. Mourners were encouraged to cry out as special instruments were used to cut holes in the mouth. After the ceremony was complete, it was believed that the dead could now eat, speak, breathe and see in the afterlife.[9]

The Egyptian pyramids are made up of various corridors, tunnels, and rooms which have different significances and uses during the burial and ritual process.[10] Texts were written and recited by priests in a very particular order, often starting in the Valley Temple and finishing in the Coffin or Pyramid Room. The variety of offerings and rituals were also most likely recited in a particular order. The Valley Temple often contained an offering shrine, where rituals would be recited.[11]

Unas

King Unas, also known as Unis or Wenis, was the last pharaoh of the fifth dynasty.[10] Of all pyramid texts, those of King Unas were considered some of the most influential. Although the shortest and smallest of all pyramid texts, Unas' texts have been used to replicate numerous texts to follow including those found in Senworsret-ankh at Lisht, from the Middle Kingdom. These texts were also the first to be discovered and later published.[1]

The pyramid texts of Unas lacked some aspects that can be found in many of the pyramids of the following pharaohs. For example, the sarcophagus of Unas is bare as opposed to inscribed.[6] While the sarcophagus was left bare, along with immediate surrounds walls, the corridor, antechamber, passage-way, and burial-chamber are all inscribed with texts and hieroglyphics. Because of its early use, the set up and layout of the Unas pyramid was replicated and expanded on for future pyramids. A canal ran along side of the pyramid, allowing boats to pass by and enter. The causeway ran 750 meters long and is still in good condition, unlike many causeways found in similar ancient Egyptian pyramids.[10]

In the pyramid of Unas, the ritual texts could be found in the underlying supporting structure, while the antechamber and corridor contained texts and spells personalized to the Pharaoh himself.[6]

Example of text from Unas

The following example comes from the pyramid of Unas. It was to be recited in the South Side Burial Chamber and Passage, and it was the Invocation To New Life.

Utterance 213:

Ho, Unis! You have not gone away dead: you have gone away alive.

Sit on Osiris's chair, with your baton in your arm, and govern the living;

with your lotus scepter in you arm, and govern those of the remote

places.

Your lower arms are of Atum, your upper arms of Atum, your belly of

Atum, your back of Atum, your rear of Atum, your legs of Atum, your

face of Anubis.

Horus's mounds serve you; Seth's mounds serve you. [12]

Queens with pyramid texts

Pyramid texts were not only found in the tombs of kings, but queens as well. Queen Neith, who was the wife of Pepi II, is one of three queens of the 5th dynasty whose tomb contains pyramid texts.[13] The other two queens (both also thought to be wives of Pepi II) Iput II and Wedjebetni also contained tombs inscribed with texts but those of Neith have been kept in much better condition.[1] Compared to the tombs of the kings, the layout and structure of those that belonged to these queens was much simpler. Though much simpler, the layout of the texts corresponded to similar walls and locations as those of the kings. For example, the Resurrection Ritual is found on the east end of the south wall. Due to the fact that the pyramid of Neith did not contain an antechamber, many of the spells normally written there were also written on the south wall.[13]

The texts of Queen Neith were similar and different to those of the kings in a few additional ways. Like those of the kings, the use of both the first and third person is present in these pyramid texts. Neith's name is used throughout the texts to make them more personal. Many of the pronouns used throughout her pyramid texts are male, indicative of the parallels between the texts of the kings and queens, but a few female pronouns can be found. The texts also contain spells and utterances that are meant to be read by both the spirit herself as well as others addressing her.[14]

Examples

After death, the king must first rise from his tomb. Utterance 373 describes:[2]

- Oho! Oho! Rise up, O Teti!

- Take your head, collect your bones,

- Gather your limbs, shake the earth from your flesh!

- Take your bread that rots not, your beer that sours not,

- Stand at the gates that bar the common people!

- The gatekeeper comes out to you, he grasps your hand,

- Takes you into heaven, to your father Geb.

- He rejoices at your coming, gives you his hands,

- Kisses you, caresses you,

- Sets you before the spirits, the imperishable stars...

- The hidden ones worship you,

- The great ones surround you,

- The watchers wait on you,

- Barley is threshed for you,

- Emmer is reaped for you,

- Your monthly feasts are made with it,

- Your half-month feasts are made with it,

- As ordered done for you by Geb, your father,

- Rise up, O Teti, you shall not die!

The texts then describe several ways for the pharaoh to reach the heavens, and one of these is by climbing a ladder. In utterance 304 the king says:[2]

- Hail, daughter of Anubis, above the hatches of heaven,

- Comrade of Thoth, above the ladder's rails,

- Open Unas's path, let Unas pass!

Another way is by ferry. If the boatman refuses to take him, the king has other plans:

- If you fail to ferry Unas,

- He will leap and sit on the wing of Thoth,

- Then he will ferry Unas to that side!

Cannibal hymn

Utterances 273 and 274 are sometimes known as the "cannibal hymn", because it describes the king hunting and eating parts of the gods:[2] They represent a discrete episode (Utterances 273-274) in the anthology of ritual texts that make up the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom period.

Appearing first in the Pyramid of Unas at the end of the Fifth Dynasty, the Cannibal Hymn preserves an early royal butchery ritual in which the deceased king—assisted by the god Shezmu—slaughters, cooks and eats the gods as sacrificial bulls, thereby incorporating in himself their divine powers in order that he might negotiate his passage into the Afterlife and guarantee his transformation as a celestial divinity ruling in the heavens.[15]

The style and format of the Cannibal Hymn are characteristic of the oral-recitational poetry of pharaonic Egypt, marked by allusive metaphor and the exploitation of wordplay and homophony in its verbal recreation of a butchery ritual.

Apart from the burial of Unas, only the Pyramid of Teti displays the Cannibal Hymn.

- A god who lives on his fathers,

- who feeds on his mothers...

- Unas is the bull of heaven

- Who rages in his heart,

- Who lives on the being of every god,

- Who eats their entrails

- When they come, their bodies full of magic

- From the Isle of Flame...

The cannibal hymn later reappeared in the Coffin Texts as Spell 573.[16] It was dropped by the time the Book of the Dead was being copied.

In popular culture

In the first scene of Philip Glass's opera Akhnaten, the phrase "Open are the double doors of the horizon" is a quotation from the Pyramid Texts. More specifically, it seems to come from Utterance 220.

The American death metal band Nile made a song, "Unas Slayer of the Gods" which contains many references to the Pyramid Texts, including the Cannibal Hymn.

In the 2001 action-adventure movie, The Mummy Returns, when Imhotep gets a jar full of dust and blows it, he quotes part of the Utterance 373 and the dust turns into mummy warriors.

The 2013 BBC programme Ripper Street, Colonel Madoc Faulkner (Iain Glen) refers to a variant of Utterance 325

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Allen, James. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. ISBN 1-58983-182-9. Retrieved 2015-10-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Lichtheim, Miriam (1975). Ancient Egyptian Literature. 1. London, England: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02899-6.

- ↑ The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day. Translation by Ogden Goelet and Raymond Faulkner; Preface by Carol Andrews; Introduction by J. Daniel Gunther; Foreword by James Wasserman (20th Anniversary ed.). San Francisco: Chronicle Books. 1994. ISBN 978-1452144382.

- ↑ Hornung, Erik (1997). The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Afterlife. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. p. 1.

- 1 2 "The Pyramid Texts: Guide to the Afterlife". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- 1 2 3 Allen, James P. (2000). Middle Egyptian: An Introduction to the Language and Culture of Hieroglyphs. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77483-7.

- 1 2 Mercer, Samuel (1956). Literary Criticism of the Pyramid Texts. London: Luzac & Compant LTD. p. 6.

- ↑ Mercer, Samuel (1956). Literary Criticism of the Pyramid Texts. London: Luzac & Company LTD. p. 76.

- ↑ "The Opening of the Mouth Ceremony". Experience Ancient Egypt. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- 1 2 3 "ANCIENT EGYPT : The Pyramid Texts in the tomb of Pharaoh Wenis, Unis or Unas". www.sofiatopia.org. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ↑ Mercer, Samuel (1956). Literary Criticism of the Pyramid Texts. London: Luzac & Company LTD. p. 15.

- ↑ Allen, James P. (2015). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. p. 34.

- 1 2 Allen, James P. (2015). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. p. 301.

- ↑ Allen, James P. (2015). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta, Georgia: Society of Biblical Literature. p. 302.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20050923100652/https://cas.memphis.edu/%7Epbrand/Egypt%20Texts/Pyramid_Texts.htm. Archived from the original on September 23, 2005. Retrieved November 30, 2011. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Faulkner, Raymond O. (2004). The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 176–178. ISBN 9780856687549.

Sources

- Wolfgang Kosack "Die altägyptischen Pyramidentexte." In neuer deutscher Uebersetzung; vollständig bearbeitet und herausgegeben von Wolfgang Kosack Christoph Brunner, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-9524018-1-1.

- Kurt Sethe Die Altaegyptischen Pyramidentexte. 4 Bde. (1908-1922)

Further reading

- Allen, James P. (2005). The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-182-7.

- Allen, James P. (2013). A New Concordance of the Pyramid Texts. Brown University.

- Forman, Werner; Quirke, Stephen (1996). Hieroglyphs and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2751-1.

- Hays, Harold M. (2012). The Organization of the Pyramid Texts: Typology and Disposition. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-227491.

- Timofey T. Shmakov, "Critical Analysis of J. P. Allen's 'The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts'," 2012.

- Clesson H. Harvey, "The Great Pyramid Texts"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid texts. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pyramid Texts |

- Kurt Sethe's original hieroglyphic transcription (1908) PT 1 - 468 online

- list of on-line resources (including translations) for further study

- Samuel A. B. Mercer translation of the Pyramid Texts

- Egyptian Pyramid Texts from Aldokkan

- The Complete Pyramid Texts of King Unas, Unis or Wenis

- Pyramid Texts Online - Read the texts in situ. Hieroglyphs & translation

- A book on the Cannibal Hymn

- The Cannibal Hymn