Giovanni Battista Piranesi

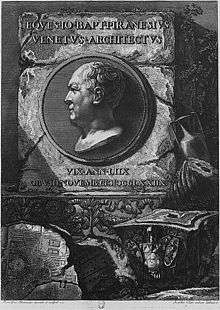

| Piranesi | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait | |

| Born |

4 October 1720 Mogliano Veneto |

| Died |

9 November 1778 (aged 58) Venice |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Education | Matteo Lucchesi |

| Known for | Etching |

| Notable work | Le Carceri d'Invenzione and etchings of Rome |

| Movement | Neoclassicism |

Giovanni Battista (also Giambattista or Piranesi) (Italian pronunciation: [dʒoˈvanni batˈtista piraˈneːzi]; 4 October 1720 – 9 November 1778) was an Italian artist famous for his etchings of Rome and of fictitious and atmospheric "prisons" (Le Carceri d'Invenzione).

Biography

Piranesi was born in Mogliano Veneto, near Treviso, then part of the Republic of Venice. His father was a stonemason. His brother Andrea introduced him to Latin language and the ancient civilization, and later he was apprenticed under his uncle, Matteo Lucchesi, who was a leading architect in Magistrato delle Acque, the state organization responsible for engineering and restoring historical buildings.

From 1740, he had an opportunity to work in Rome as a draughtsman for Marco Foscarini, the Venetian ambassador of the new Pope Benedict XIV. He resided in the Palazzo Venezia and studied under Giuseppe Vasi, who introduced him to the art of etching and engraving of the city and its monuments. Giuseppe Vasi found Piranesi's talent was beyond engraving. According to Legrand, Vasi told Piranesi that "you are too much of a painter, my friend, to be an engraver."

After his studies with Vasi, he collaborated with pupils of the French Academy in Rome to produce a series of vedute (views) of the city; his first work was Prima parte di Architettura e Prospettive (1743), followed in 1745 by Varie Vedute di Roma Antica e Moderna.

From 1743 to 1747 he sojourned mainly in Venice where, according to some sources, he often visited Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, a leading artist in Venice. It was Tiepolo who expanded the restrictive conventions of reproductive, topographical and antiquarian engravings. He then returned to Rome, where he opened a workshop in Via del Corso. In 1748–1774 he created a long series of vedute of the city which established his fame. In the meantime Piranesi devoted himself to the measurement of many of the ancient edifices: this led to the publication of Le Antichità Romane de' tempo della prima Repubblica e dei primi imperatori ("Roman Antiquities of the Time of the First Republic and the First Emperors"). In 1761 he became a member of the Accademia di San Luca and opened a printing facility of his own. In 1762 the Campo Marzio dell'antica Roma collection of engravings was printed.

The following year he was commissioned by Pope Clement XIII to restore the choir of San Giovanni in Laterano, but the work did not materialize. In 1764, one of Pope's nephews, Cardinal Rezzonico, appointed him to start his sole architectural works of importance, the restoration of the church of Santa Maria del Priorato in the Villa of the Knights of Malta, on Rome's Aventine Hill. He combined certain ancient architectural elements, trophies and escutcheons, with a venetian whimsicality for the facade of the church and the walls of the Piazza dei Cavalieri di Malta. This was the only time he expressed himself in actual marble and stone.

In 1767 he was made a knight of the Golden Spur, which enabled him henceforth to sign himself "Cav[aliere] Piranesi". In 1769 his publication of a series of ingenious and sometimes bizarre designs for chimneypieces, as well as an original range of furniture pieces, established his place as a versatile and resourceful designer.[1] In 1776 he created his best known work as a 'restorer' of ancient sculpture, the Piranesi Vase, and in 1777–78 he published Avanzi degli Edifici di Pesto (Remains of the Edifices of Paestum).

He died in Rome in 1778 after a long illness, and was buried in the Church he had helped restore, Santa Maria del Priorato. His tomb was designed by Giuseppi Angelini.

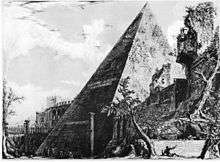

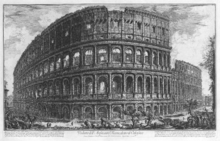

The Views (Vedute)

Even though the social structure by an aristocracy remained rigid and oppressive, Venice revived through the Grand Tour as the center of intellectual and international exchange in the eighteenth century. The ideas of the Enlightenment stimulated theorists and artists all over Europe including Paris, Dresden, and London. New forms of artistic expression emerged: veduta, capriccio, and veduta ideata, topographical view, architectural fantasy, accurate renderings of ancient monuments assembled with imaginary compositions in response to the demand of increased visitors.

The developing center of the Grand Tour was Rome. Rome became a new meeting place and intellectual capital of Europe for the leaders of a new movement in the arts. The city was attracting artists and architects from all over Europe beside the Grand Tourists, dealers and antiquarians. While many came through official institutions such as the French Academy, others came to see the new discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii. Coffee shops were frequent gathering places, most famously the Antico Caffè Greco, established 1760. The Caffe degli Inglesi opened several years later, at the foot of the Spanish Steps in Piazza di Spagna, with wall paintings by Piranesi. With his own print workshop and museo of antiquities nearby, Piranesi was able to cultivate relationships in both places with wealthy buyers on the tour, particularly English.[2]

The remains of Rome kindled Piranesi's enthusiasm. Informed by his experience in Venice and his study of the works of Marco Ricci and particularly Giovanni Paolo Panini, he appreciated not only the engineering of the ancient buildings but also the poetic aspects of the ruins. He was able to faithfully imitate the actual remains; his invention in catching the design of the original architect provided the missing parts. His masterful skill at engraving introduced groups of vases, altars, tombs that were absent in reality; his manipulations of scale; and his broad and scientific distribution of light and shade completed the picture, creating a striking effect from the whole view. Some of his later work was completed by his children and several pupils.

Piranesi's son and coadjutor, Francesco, collected and preserved his plates, in which the freer lines of the etching-needle largely supplemented the severity of burin work. Twenty-nine folio volumes containing about 2000 prints appeared in Paris (1835–1837).

The late Baroque works of Claude Lorrain, Salvatore Rosa, and others had featured romantic and fantastic depictions of ruins; in part as a memento mori or as a reminiscence of a golden age of construction. Piranesi's reproductions of real and recreated Roman ruins were a strong influence on Neoclassicism.

One of the main features of Neo-Classicism is the attitude towards nature and the uses of the past. Neo-Classicism was prompted by the discoveries at Herculaneum and Pompeii. Rediscovery and revaluation of Greece, Egypt, and Gothic was also active as well as the various expeditions of unfamiliar Roman empire. The view of a Golden Age was changing from static to mutable, inspired by Rousseau and Winckelmann in response to the dynamic growth of society.

The wider perspective on the past created a new way of expression. Artists developed a greater self-consciousness in confronting the limited authority of the ancient world, and there was a growing interest in civilizations and the destiny of nations. Piranesi was especially interested in the Graeco-Roman debate in the 1760s, between followers of Winckelmann who thought Greek culture and architecture superior to their Roman counterparts, and those who (like Piranesi) believed that the Romans had improved upon their Greek models.[3] His free relationship to the past may be summarized in a phrase of his that become a mantra: "col sporcar si trova"; "by messing about, one discovers".[4]

Throughout his lifetime, Piranesi created numerous prints depicting the Eternal City; these were widely collected by gentlemen on the Grand Tour. The Lobkowicz Collections, housed at the Lobkowicz Palace, contains a group of twenty-six 18th-century engravings of views of modern and ancient Rome created by Giovanni Battista Piranesi.

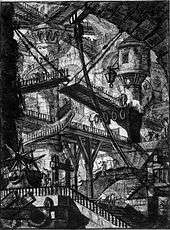

The Prisons (Carceri)

The Prisons (Carceri d'invenzione or 'Imaginary Prisons'), is a series of 16 prints produced in first and second states that show enormous subterranean vaults with stairs and mighty machines.

These images influenced Romanticism and Surrealism. While the Vedutisti (or "view makers") such as Canaletto and Bellotto, more often reveled in the beauty of the sunlit place, in Piranesi this vision takes on what from a modern perspective could be called a Kafkaesque distortion, seemingly erecting fantastic labyrinthine structures, epic in volume. They are capricci, whimsical aggregates of monumental architecture and ruin.

The series was started in 1745. The first state prints were published in 1750 and consisted of 14 etchings, untitled and unnumbered, with a sketch-like look. The original prints were 16" x 21". For the second publishing in 1761, all the etchings were reworked and numbered I–XVI (1–16). Numbers II and V were new etchings to the series. Numbers I to IX were all done in portrait format (vertical), while X to XVI were landscape format (horizontal+). Though untitled, their conventional titles are:

- I – Title Plate

- II – The Man on the Rack

- III – The Round Tower

- IV – The Grand Piazza

- V – The Lion Bas-Reliefs

- VI – The Smoking Fire

- VII – The Drawbridge

- VIII – The Staircase with Trophies

- IX – The Giant Wheel

- X – Prisoners on a Projecting Platform

- XI – The Arch with a Shell Ornament

- XII – The Sawhorse

- XIII – The Well

- XIV – The Gothic Arch

- XV – The Pier with a Lamp

- XVI – The Pier with Chains

Thomas De Quincey in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater (1820) wrote the following:

Many years ago, when I was looking over Piranesi's Antiquities of Rome, Mr. Coleridge, who was standing by, described to me a set of plates by that artist ... which record the scenery of his own visions during the delirium of a fever: some of them (I describe only from memory of Mr. Coleridge's account) representing vast Gothic halls, on the floor of which stood all sorts of engines and machinery, wheels, cables, pulleys, levers, catapults, etc., etc., expressive of enormous power put forth, and resistance overcome. Creeping along the sides of the walls, you perceived a staircase; and upon it, groping his way upwards, was Piranesi himself: follow the stairs a little further, and you perceive it come to a sudden abrupt termination, without any balustrade, and allowing no step onwards to him.

In the second publishing, some of the illustrations appear to have been edited to contain (likely deliberate) impossible geometries.[5]

An in-depth analysis of Piranesi's Carceri was written by Marguerite Yourcenar in her Dark Brain of Piranesi: and Other Essays (1984). Further discussion of Piranesi and the Carceri can be found in The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi by John Wilton-Ely (1978). The style of Piranesi was imitated by twentieth-century forger Eric Hebborn.

Archaeologist

It is important to look at his contribution as an archaeologist, which was acknowledged at the time as he had been elected to the London Society of Antiquaries. His influence of technical drawings in antiquarian publications is often overshadowed. He left explanatory notes in the lower margin about the structure and ornament. Most ancient monuments in Rome were abandoned in fields and gardens. Piranesi tried to preserve them with his engravings. To do this, Piranesi pushed himself to achieve realism in his work. A third of the monuments in Piranesi's engravings have disappeared, and the stucco and surfacings were often stolen, restored and modified clumsily. Piranesi's precise observational skills allow people to experience the atmosphere in Rome in the eighteenth century. Piranesi may have recognised his role to disseminate remarkable information through meaningful images. He became the Director of the Portici Museum in 1751.

References

- ↑ Wilton-Ely, John. "The ultimate act of fantasia: To mark the opening of a major Piranesi exhibition at Cooper-Hewitt National Design Museum, New York, one of its curators, John Wilton-Ely, discusses the masterpiece that Piranesi planned for his own tomb." Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine., Apollo (magazine), 2007-09-01. Retrieved on 2009-06-01.

- ↑ Lowe, Adam. "Messing About With Masterpieces: New Work by Giambattista Piranesi (1720-1778)," Art in Print Vol. 1 No. 1 (May-June 2011), p. 19

- ↑ Gontar, Cybele, Neoclassicism, The Heilbrunn Timeline of art History, metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-07-02.

- ↑ Lowe, Art in Print Vol. 1 No. 1, p. 14-15.

- ↑ ""Piranesi's Carceri as Inconsistent"". The University of Adelaide -- Inconsistent Images. November 2007. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- Attribution

Further reading

- Ficacci, L. (2000). Giovanni Battista Piranesi: The Complete Etchings. Cologne and Rome.

- Focillon, Henri (1918). Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Essai de catalogue raisonné de son oeuvre. Paris.

- Hofer, P., 1973. The Prisons (Le Carceri) – The complete first and second states. New York: Dover publications.

- Maclaren, Sarah F. (2005). La magnificenza e il suo doppio. Il pensiero estetico di Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Milan: Mimesis. ISBN 88-8483-248-9

- Miller, N. (1978). Archäologie des Traums. Versuch über Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Munich and Vienna.

- Tafuri, Manfredo (1986). La sfera e il labirinto : Avanguardia e architettura da Piranesi agli anni '70. Turin: Giulio Einaudi.

- Tafuri, Manfredo. (1976). Architecture and Utopia. Design and Capitalist Development. Cambridge, MA/London: MIT Press. tr. Barbara Luigia La Penta.

- Wilton-Ely, J. (1978). The Mind and Art of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Wilton-Ely, J. (1994). Giovanni Battista Piranesi: The Complete Etchings – an Illustrated Catalogue. Vols. 1 & 2. San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts publications.

- Yourcenar, Marguerite (1985). The Dark Brain of Piranesi: And Other Essays. Henley-on-Thames: Ellis.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giovanni Battista Piranesi. |

- Opere di Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1835–1839)

- Wikiart.org, Collected Piranesi works in hi-rez, Vedute di Roma, Carceri, Le antichità Romane and Collection of drawings engraved after Guercino.

- All 940 images from that 29 volumes complete works edition (hi-res versions clickable; English interface with Italian and French text; from Tokyo university)

- Antichita Romanae

- Antichita Romanae (1748) (914 pages in 17 volumes; from BNF)

- Vedute di Roma (Hi-res images from "Vedute di Roma", vol. 17 of "Antichita Romanae"; digitized by Leyden university)

- Ancient Rome (1748) (87 hi-res pics, jpg )

- Carceri

- Prisons of the Imagination (images from the exhibition of the Carceri, low-res)

- First state of Carceri (1750; 14 sketches in hi-res; digitized by Leyden university)

- Carceri (Full hi-res Album, 16 pics)

- Animation film as a walkthrough of the Carceri (video 10 min 40 s)

- Other

- Perspectives (28 Works Depicting Perspective in Architecture)

- Antichita Romane, 4 Architectural Etchings (1756) Kenneth Franzheim II Rare Books Room, William R. Jenkins Architecture and Art Library, University of Houston Digital Library.

- Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Giovanni Battista Piranesi (see index)

- Della Magnificenza Ed Architettvra De'Romani / De Romanorvm Magnificentia Et Architectvra (Rome, 1761; digitized by Heidelberg University)

- Osservazioni Di Gio. Battista Piranesi sopra la Lettre de M. Mariette aux auteurs de la Gazette Littéraire de l'Europe (Rome, 1765; digitized by Heidelberg university)

- 137 Piranesi etchings in good resolution

- Promenades Of An Art Impressionist – Piranesi