Line of Control

Coordinates: 34°56′N 76°46′E / 34.933°N 76.767°E

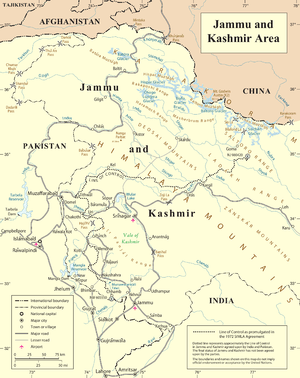

The term Line of Control (LoC) refers to the military control line between the Indian and Pakistani controlled parts of the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir—a line which does not constitute a legally recognized international boundary, but is the de facto border. Originally known as the Cease-fire Line, it was redesignated as the "Line of Control" following the Simla Agreement, which was signed on 3 July 1972. The part of the former princely state that is under Indian control is known as the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The Pakistani-controlled part is divided into Azad Jammu and Kashmir and Gilgit–Baltistan. The northernmost point of the Line of Control is known as NJ9842. India–Pakistan border continues from the southernmost point on the LoC.

Another ceasefire line separates the Indian-controlled state of Jammu and Kashmir from the Chinese-controlled area known as Aksai Chin. Lying further to the east, it is known as the Line of Actual Control (LAC).

Former US President Bill Clinton has referred to the Indian subcontinent and the Kashmir Line of Control, in particular, as one of the most dangerous places in the world.[1][2]

Legacy

The Line of Control divided Kashmir into two parts and closed the Jehlum valley route, the only entrance and exit of the Kashmir Valley at that time. This territorial division, which to this day still exists, severed many villages and separated family members from each other.[3][4]

Positions

Pakistani

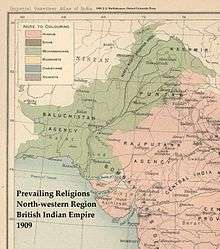

The Pakistan Declaration of 1933 had envisioned the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir as one of the "five Northern units of India" that were to form the new nation of Pakistan, on the basis of its Muslim majority. Pakistan still claims the whole of Kashmir as its own territory, including Indian-controlled Kashmir. India has a different perspective on this interpretation.

Indian

Maharaja Hari Singh, King of the princely state of Kashmir and Jammu agreed to Governor-General Mountbatten's[5][6] suggestion to sign the Instrument of Accession India demanded accession in return for assistance. India claimed that the whole territory of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir had become Indian territory (India's official posture) due to the accession, it claims the whole region, including Azad Kashmir territory, as its own.

Indian Line of Control fencing

The Indian Line of Control fencing is a 550 km (340 mi) barrier along the 740 km (460 mi) disputed 1972 Line of Control (or ceasefire line). The fence, constructed by India, generally remains about 150 yards on the Indian-controlled side. Its stated purpose is to exclude arms smuggling and infiltration by Pakistani-based separatist militants.[7]

The barrier itself consists of double-row of fencing and concertina wire eight to twelve feet (2.4–3.7 m) in height, and is electrified and connected to a network of motion sensors, thermal imaging devices, lighting systems and alarms. They act as "fast alert signals" to the Indian troops who can be alerted and ambush the infiltrators trying to sneak in. The small stretch of land between the rows of fencing is mined with thousands of landmines.[8][9]

The construction of the barrier was begun in the 1990s, but slowed in the early 2000s as hostilities between India and Pakistan increased. After a November 2003 ceasefire agreement, building resumed and was completed in late 2004. LoC fencing was completed in Kashmir Valley and Jammu region on 30 September 2004.[10] According to Indian military sources, the fence has reduced the numbers of militants who routinely cross into the Indian side of the disputed state to attack soldiers by 80%.[11]

Pakistan has criticised the construction of the barrier, saying it violates both bilateral accords and relevant United Nations resolutions on the region.[12] The European Union has supported India's stand calling the fencing as "improvement in technical means to control terrorists infiltration" and also pointing that the "Line of Control has been delineated in accordance with the 1972 Shimla agreement".[12]

Crossing Points

There are three main crossing points on the LoC currently operational.

Chakan Da Bagh

A road connects Tatrinote in Pakistan side of the LoC to Indian Poonch district of Jammu and Kashmir through Chakan Da Bagh crossing point.[13][14] It is a major route for cross LoC trade and travel. Banking facilities and a trade facilitation centres are being planned on the Indian side for the benefit of traders.[15]

The flag meetings between Indian and Pakistani security forces are held here. These meetings are held at the border or on the Line of Control by commanders of the Army on both sides. A flag meeting can also be held at the Brigadier level on smaller issues.[16] If the meeting is on a larger context, it could be held on the General level[17]

Salamabad

Salamabad crossing point is located in the Uri area of Baramulla district of Jammu and Kashmir along the Indo-Pak LoC.[13] It is a major route for cross LoC trade and travel. Banking facilities and a trade facilitation centres are being planned on the Indian side.[15]

Kaman Aman Setu

The name in english translates to "bridge of peace" is located in Uri. The bridge was rebuilt by Indian army after the 2005 Kashmir earthquake when a mountain on the Pakistani side had caved in.[18] This route was opened for trade in 2008 after a period of 61 years.[19] The Srinagar–Muzaffarabad Bus passes through this bridge on the LoC.[20]

See also

- Wagah, an international border crossing between India and Pakistan

- Indo-Bangladeshi barrier

- Kashmir conflict

- Actual Ground Position Line

- Wakhan

- Siachen conflict

References

- ↑ Analysis: The world's most dangerous place?

- ↑ 'Most dangerous place'

- ↑ Ranjan Kumar Singh, Sarhad: Zero Mile, (Hindi), Parijat Prakashan, ISBN 81-903561-0-0

- ↑ Women in Security, Conflict Management, a Peace (Program) (2008). Closer to ourselves: stories from the journ towards peace in South Asia. WISCOMP, Foundation for Universal Responsibility of His Holiness the Dalai Lam 2008. p. 75. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Viscount Louis Mountbatten, the last Viceroy of British India, stayed on in independent India from 1947 to 1948, serving as the first Governor-General of the Union of India.

- ↑ Stein, Burton. 1998. A History of India. Oxford University Press. 432 pages. ISBN 0-19-565446-3. Page 368.

- ↑ "cross-border infiltration and terrorism" Archived 21 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "LoC fencing in Jammu nearing completion". The Hindu. Feb 1, 2004. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- ↑ "Mines of war maim innocents". Tehelka.

- ↑ "LoC fencing completed: Mukherjee". The Times Of India. 16 December 2004.

- ↑ "Harsh weather likely to damage LoC fencing". Daily Times. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-31.

- 1 2 "EU criticises Pak's stand on LoC fencing". Express India. Dec 16, 2003. Retrieved 23 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Jammu and Kashmir: Goods over Rs 3,432 crore traded via two LoC points in 3 years". Economic Times. PTI. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ Chakan-da-Bagh Archived 2013-01-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Cross-LoC trade at Rs 2,800 crore in last three years". Economic Times. PTI. 13 June 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "India, Pakistan hold flag meeting". The Hindu. 23 August 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Flag meet held to defuse LoC tension at Chakan da Bagh". The Tribune. 24 August 2017. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "J&K CM inaugurates rebuilt Aman Setu". hindustan Times. 21 February 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Trucks start rolling, duty-free commerce across LoC opens". Livemint. 21 October 2008. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ↑ "Re-erected Kaman Aman Setu will be inaugurated on Monday". Outlook. 19 February 2006. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

Further reading

- Ranjan Kumar Singh, Sarhad: Zero Mile, (Hindi), Parijat Prakashan, ISBN 81-903561-0-0