Corporation tax in the Republic of Ireland

.png)

Brad Setser & Cole Frank (CoFR).[3]

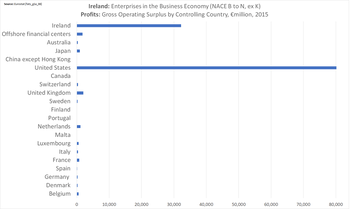

The Irish corporation tax regime is central to Ireland's economy. Foreign multinationals pay 80% of Irish corporate tax, employ 25% of the Irish labour force (indirectly pay 50% of Irish salary taxes), and create 57% of Irish OECD non-farm value-add. U.S.-controlled multinationals represent almost all foreign corporations in Ireland and are 14 of the top 20 Irish firms, and 70% of the revenue of the top 50 Irish firms (§ Low tax economy). Ireland has the most U.S. § Corporate tax inversions, and Apple is one-fifth of Irish GDP. Academics rank Ireland as the largest corporate tax haven; larger than the total Caribbean tax haven system.[5]

While Ireland's "headline" corporation tax rate is 12.5%, the evidence is that foreign multinationals pay an § Effective tax rate (ETR) of under 4% on all global profits that they can "shift" to Ireland, via Ireland's 72 bilateral tax treaties. These lower effective tax rates are achieved by a complex set of Irish base erosion and profit shifting ("BEPS") tools which handle the largest BEPS flows in the world (e.g. the double Irish as used by Google and Facebook, the single malt as used by Microsoft and Allergan, and capital allowances for intangible assets as used by Accenture, and by Apple post Q1 2015).[1]

Ireland's § Multinational tax schemes use "intellectual property" ("IP") accounting to affect the BEPS movement. This is why almost all foreign multinationals are from the industries with substantial IP, being technology and life sciences. Jurisdictions with "territorial" tax systems (i.e. almost all OECD countries), do not need Ireland's BEPS tools. Thus, almost all material foreign multinationals based in Ireland, date from a time when their home tax system was a "worldwide" system (e.g. U.K. pre-2009 and U.S. pre-2017), and is why there are no non-U.S./non-U.K. multinationals in Ireland's top 50 firms. Ireland is sometimes described as a "U.S. corporate tax haven".

As with all corporate tax havens, Ireland's economic statistics, including GDP and GNP, are distorted by BEPS accounting flows. The EU estimated that 23% of Ireland's GDP from 2010-2015 was artificial.[6] This distortion escalated when Apple executed the largest BEPS transaction in history, on-shoring circa $300 billion of non-U.S. IP to Ireland in Q1 2015 (called "leprechaun economics"). It forced the Central Bank of Ireland to abandon GDP and GNP in 2017, and replace with modified gross national income (GNI*), which removes part of the BEPS tool distortions. Irish GDP was 143% of Irish GNI* in 2016.

Ireland's corporation tax regime is integrated with Ireland's IFSC tax schemes (e.g. Section 110 SPVs and QIAIFs), which offer traditional tax haven-type tools to give confidential routes out of the Irish corporate tax system to Ireland's favoured Sink OFC, Luxembourg, which is 50% of all outbound Irish FDI.[7] This functionality has made Ireland one of the largest global Conduit OFCs, and the fourth largest global shadow banking centre.[8] Irish privacy and data protection laws hide Irish tax tools from public scrutiny. There is evidence Ireland behaves like a "captured state", fostering tax avoidance schemes. Ireland is "labeled a tax haven".

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") moves the U.S to a "territorial" tax system. The TJCA's GILTI-FDII-BEAT taxes have seen U.S. IP-heavy multinationals (e.g. Pfizer) forecast 2019 tax rates are similar to those of U.S. inversions to Ireland (e.g. Medtronic). Ireland's corporate tax regime is also threatened by the EU's desire to introduce EU-wide anti-BEPS tool regimes (e.g. the 2020 Digital Services Tax, and proposed CCCTB). However, by accepting Irish capital allowances in its GILTI calculation, the TCJA has accidentally made Apple's 2015 Green Jersey BEPS tool more attractive to U.S. firms who can achieve U.S. tax rates of 0-3% by using it.

"Without its low-tax regime [from the TCJA], Ireland will find it hard to sustain economic momentum"

Low tax economy

Ireland's economic model was transformed from a predominantly agricultural based economy to a knowledge-based economy, with the creation of a 10% low-tax special economic zone called the International Financial Services Centre ("IFSC") in Dublin city centre in 1987.[10][11] The transformation was accelerated when the entire country was "turned into an IFSC", by reducing Ireland's corporate tax rate from 32% to 12.5% (phased in from 1998-2003).[12] The additional passing of the important 1997 Taxes and Consolidated Acts leglislation, laid the legal foundations for the BEPS tax schemes used by foreign multinationals in Ireland today (i.e. double Irish, capital allowances for intangible assets and Section 110 SPVs) to achieve effective Irish CT rates of 0-3% (see § Effective tax rate (ETR)).

While Ireland is committed to a policy of low (and even ultra-low), corporate tax rates, Ireland's non-corporate taxes (including VAT) are in line with EU-28 tax rates (if not higher than average). Ireland's approach to taxes is summarised by the OECD's "Hierarchy of Taxes" pyramid (reproduced in the Department of Finance Tax Strategy Group's 2011 corporate tax policy document).[13]

Acclaimed Irish writer, Fintan O'Toole has labeled Ireland's focus on U.S. multinational tax BEPS strategies as its core economic model, as Ireland's OBI, (or "One Big Idea").[14]

Multinational economy

As a result of these policies, foreign-controlled multinationals dominate Ireland's economy. For example, they:

- Directly employ one-quarter of the Irish private sector workforce;[15]

- Pay these employees an average wage of €85k (€17.9bn wage roll on 210,443 staff)[16] vs. Irish Industrial wage of €35k;

- Directly contribute €28.3bn annually in taxes, wages and capital spending;[16]

- Pay 80% of all Irish corporation and business taxes;[17][18]

- Potentially pay over 50% of all Irish salary taxes (due to higher paying jobs), 50% of all Irish VAT, and 92% of all Irish customs and excise duties;

(this was claimed by a leading Irish tax expert (and Past President of the Irish Tax Institute), but is not fully verifiable)[19] - Create 57% of private sector non-farm value-add (40% of value-add in Irish services and 80% of value-add in Irish manufacturing);[20][15]

- Make up 14 of the top 20 Irish companies (by 2017 turnover) (see table § Mostly US multinationals).[21]

- American Chamber of Commerce (Ireland) estimates the value of U.S. investment in Ireland at €334bn, exceeding Irish GDP (€291bn in 2016).[22]

Multinational features

There are a number of interesting features to foreign multinationals in Ireland:

- They are mostly US-based. U.S.-controlled multinationals are 80% of foreign multinational employment in Ireland (the balances are UK pharmaceutical and UK retailers).[23][16] 14 of Ireland's 20 largest companies (by 2017 turnover) are US-based (see § Mostly US multinationals).[21] There are no non-US/non-UK foreign multinationals in Ireland's top 50 companies by turnover, and only one by employees (No. 41, the German food retailer Lidl, who is in Ireland solely to sell to Irish customers).[21]

(Note, some lists are compiled by asset size, which includes large SPV-type IFSC European financials with billions in assets, but small employees and turnover, in tax-free section 110 SPVs)

- They are very concentrated. The top 20 corporate taxpayers pay 50% of all Irish corporate taxes while the top 10 pay 40% of all Irish corporate taxes.[17][18] Post leprechaun economics, Apple, Ireland's largest company by turnover, constitutes almost one fifth of Ireland's GDP (Apple's ASI 2014 profits of €34bn per annum, are almost 20% of Irish GNI*).[24][25][26][27]

- They are mostly technology and life sciences. To use Ireland's "multinational tax schemes", a multinational needs to have intellectual property (or "IP"),[28] which is then converted into intellectual capital and royalty payments plans, to move funds from high-tax locations. Most global IP - and multinationals in Ireland - is concentrated in these two sectors.[21][17]

- They use Ireland to shield all non-US profits, not just EU profits, from the US "worldwide tax" system. Non-US multinationals hardly use Ireland (there are no non-UK/non-US foreign firms in the top 50 Irish companies, by turnover[21]). This is because their home countries have "territorial tax" systems with lower rates on foreign income.[29] Pre the 2017 TCJA, US multinationals used Ireland to shield all non-US income, not just European, from the US 35% "worldwide tax" system.[30] In 2018, Facebook Ireland revealed that 1.5bn of its 1.9bn accounts in Ireland, were not European.[31]

- They artificially inflate Irish GDP by 50%. The tax plans of multinationals distort Irish GDP (and GNP).[20] The EU found 23% of Irish 2010-2014 GDP was royalty payments (ratio of GNI to GDP was 77%).[6] Post Apple's leprechaun economics re-structuring,[32][33] it is estimated Irish GDP is 150% of Irish GNI (vs. 100% in EU-28).[34][35] The CBI has proposed replacing GDP with modified GNI.

- They pay effective tax rates of 0-3%. Irish Revenue quote an effective 2015 CT rate of 9.8%,[17] but this omits profits deemed not taxable.[36] The US Bureau of Economic Analysis gives an effective 2015 Irish CT rate of 2.5%.[18][12] BEA agrees with the Irish CT rates of Apple, Google and Facebook (<1%),[37][38][39], and the CT rates of the main tax schemes (0-3%).[40][41][42] (§ Effective tax rate (ETR))

Multinational job focus

Ireland's low-tax system emphasises job creation. To avail of the Irish "multinational tax schemes" (see below), which deliver effective Irish tax rates of 0-3%, the multinational must meet conditions on the intellectual property ("IP") they will be using as part of their scheme. This is outlined in the Irish Finance Acts particular to each scheme, but in summary, the multinational must:[43][44]

- Prove that they are carrying out a "relevant trade" on the IP in Ireland (i.e. Ireland is not just an "empty shell" through which IP passes en route to a tax-haven);

- Prove that the level of Irish employment doing "relevant activities" on the IP is consistent with the Irish tax relief being claimed (the exact ratio has never been disclosed);

- Show that the average wages of the Irish employees are consistent with such a "relevant trade" (i.e. must be "high-value" jobs earning +€60,000-€90,000 per annum);

- Put this into an approved "business plan" (agreed with Revenue Commissioners and other State bodies), for the term of the tax relief scheme;

- Agree to suffer "clawbacks" of the tax relief granted (pay the full 12.5% level), if they leave before the end plan (at least 5 years for schemes started after February 2013)[45]

The IDA Ireland disclosed 2016 foreign multinational figures of €17.9bn wage roll on 210,443 staff, or €85k per employee ("high-value" jobs).[16]

In practice, there are few cases of US technology multinationals conducting material software engineering/programming work in Ireland. The "high-value" Irish jobs tend to be "localisation" work (i.e. converting software into different languages) or "sales and marketing" work. These are sufficient to meet the Irish Revenue Commissioners criteria for a "relevant trade" and "relevant activities".[46][47]

The % of Irish wage-roll to Irish gross profits has never been disclosed. However, commentators imply wage-roll needs to be circa 2-3% of gross shielded profits (i.e. a tax of 2-3%)

For example:

- Apple employed 6,000 people in 2014, and at say €100,000 cost per employee gives a €600m wage roll on ASI 2014 gross profits of €25bn (see table below),[48][47] or 2.4%

- Google employed 2,763 people in 2014, and at say €100,000 cost per employee gives a €276m wage roll on Google 2014 gross profits of €12bn,[49] or 2.3%

In total, therefore, a US multinational should pay a total Irish tax of 2-6% (actual Irish tax of 0-3%, plus Irish employment costs of 2-3%).

Note that Ireland's requirement that foreign multinationals pay an effective "employment tax" makes Ireland even more attractive for locating intellectual property (or IP) to execute IP-based BEPS tools post the OECD's Article 5 of the Multilateral Instrument (which seeks to end "letterbox" type IP locations, and encourage locations where work is being performed on the IP, even if the goal is still tax driven).[50]

Tax system (March 2018)

Tax rates

There are two rates of corporation tax ("CT") in the Republic of Ireland:[51][45][52][53]

- 12.5% for trading income (or active businesses income)

- 25% for non-trading income (or passive income) covering investment income, rental income, net profits from foreign trades, and income from certain land dealings and oil, gas and mineral exploitations.

The "special rate" of 10% for companies involved in manufacturing, the International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) or the Shannon Free Zone ended on 31 December 2003.[54]

Key aspects

- Low rate - At 12.5%, Ireland has one of the lowest corporate tax rates in Europe (Hungary 9% and Bulgaria 10% are lower) and half the OECD average (24.9%).[45][55]

- Highly transparent/compliant - As a CT system used by major multinationals as a global Conduit OFC for tax management, it is fully compliant with EU/OECD guidelines.[56][57][58]

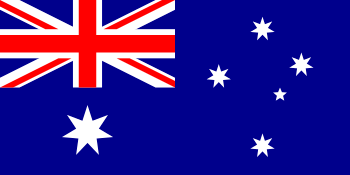

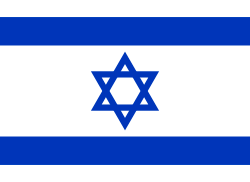

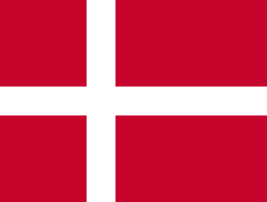

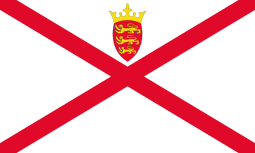

- Worldwide system - Post the US 2017 TCJA, Ireland is one of 6 remaining OECD countries using a "worldwide tax" system (Chile, Greece, Ireland, Israel, South Korea, Mexico).[45][59]

- No thin capitalisation - Ireland has no thin capitalisation rules (which means Irish corporates can be financed with 100% debt).[52]

- Double Irish residency - Pre January 2015, Irish CT was based on where a company was "managed and controlled" (vs. registered), this "double Irish" system ends in 2020.[45][52]

- Single Malt residency - While double Irish was closed in 2015, it can be recreated by "managed and controlled" wordings in selective Irish tax treaties (i.e. Malta, UAE).[45][52]

- Extensive treaties - As of March 2018, Ireland has double-tax treaties with over 73 countries (the 74th, Ghana, is pending).[60][45]

- Holding company regime - Built for corporate inversions, enables Irish based holding companies gain full tax relief against withholding taxes, foreign dividends and CGT.[52][45]

- Intellectual property regime - Built for technology firms, recognises a wide range of intellectual assets that can be depreciated against Irish tax (over 5 years, post-February 2013).[45]

- First OECD KDB - Ireland created the first OECD compliant Knowledge Development Box in 2016 to further support its intellectual property regime.[45]

Key statistics

(As at the 2017 Revenue Commissioners, and the office of Comptroller & Auditor General, reports into 2016 Irish corporation tax ("CT"))[17][18]

- Irish corporation 2016 CT was €7.35bn, which is 15% of total Irish exchequer taxes (vs. 7.7% for OECD average) and 2.7% of Irish GDP (vs. 2.7% OCED average).[17][18]

(Note: Irish GDP, post the leprechaun economics affair is considered unreliable. Irish GNI* (30% below Irish GDP) is preferred by the Central Bank of Ireland).

- Over 80% of Ireland's corporate tax from 2010-2016[61], and in 2016 alone[17], came from foreign owned multinationals based in Ireland.[62]

(Note: IDA Ireland state that US-owned multinationals represent almost 80% of multinational employment in Ireland, thus implying US multinationals are circa 64% of CT revenues)

- The top 20 multinationals provide almost half of all Irish corporate taxation, while the top 10 provide circa 37% (up from 16%, 17% in 2006, 2007).[17][63][61]

- Three sectors make up over 70% of CT - Finance & Insurance (which can relate to IT), Manufacturing (mostly pharmaceutical) and Information Technology.[18]

(Note: It is not possible to separate out the financing companies (appear under Finance & Insurance), of the US technology multinationals)

- The increasing concentration of Irish CT around a handful of (mostly US) multinationals has been noted as a risk factor by the Irish Fiscal Advisory Council[64]

- Ireland's "headline" CT rate is 12.5%, but the effective 2015 CT rate is between 2.5% to 15.5% depending which of 8 methods are used (and what is "excluded" from taxable profits).[18]

(Note: The effective 2015 CT rate of 9.8% from Irish Revenue excludes profits not taxable under the main tax schemes".[37][41][42][40] (§ Effective tax rate (ETR))[36]

Recent trends

Up until 2014, Irish CT yearly returns (see "yearly returns" below) had been growing steadily with the Irish economic recovery. At just over €4.61bn in 2014, Irish CT returns were still below the pre-crisis levels of circa €5-6bn. Irish CT as a % of total Irish taxation was just over 10%.[18]

In 2015, at the same time that Apple has created the leprechaun economics moment, Irish CT jumped materially to €6.87bn (a €2.26bn, or 49% increase, in one year).[17][18] It was noted that Finance Minister Michael Noonan made Apple's 2015 capital allowances for intangible assets scheme tax-free by increasing the cap in the 2015 Irish Budget to 100% (reversed in 2017, but for new schemes only).[65] It was also noted that Apple's main Irish subsidiary, ASI, was recording gross profits of €25bn in 2014,[24] while the total rise in 2015 intangible assets claimed under Irish capital allowances was €26.220bn.[17]

As with leprechaun economics in 2015, commentators believe this CT jump is due to Apple, and more than ASI was re-structured into Ireland, however, we may never know the answer.[3] The "clawback" on Apple's new capital allowances for intangible assets scheme expires in January 2020 (5-year term[66][51]). At the time of the CT jump disclosure, the Irish Government commissioned a study of Irish CT sustainability which confirmed visibility to 2020 but not beyond.[67][68][69]

Multinational tax schemes

Mostly US multinationals

Feargal O'Rourke

CEO PwC (Ireland)

"Architect" of the double Irish[70][71]

Irish tax planning schemes, with effective tax rates of 0-3%,[40] require intellectual property ("IP"), which is converted into royalty payment ("RP") schemes in order to profit shift between jurisdictions.[72][73] IP is becoming the leading BEPS tool for tax avoidance,[74][28] and Ireland has some of the most advanced IP-based BEPS tools. Ironically, the OECD BEPS project is fully protective of IP (the OECD having championed IP for decades).[75] For example, the Irish capital allowances for intangible assets scheme, allows IP to be converted into intangible assets ("IA"), which can be "onshored" to Ireland in an intergroup transaction (i.e. like a quasi-corporate tax inversion), and written off against Irish tax (effective tax rate of 0-3%)[76] in perpetuity (IP is renewed on each product cycle).

The requirement for high levels of IP for Irish multinational base erosion and profit shifting schemes, limits the use of Irish corporate tax schemes to industries and companies that produce the most IP in the world, namely, technology (Apple, Google, Microsoft, Dell), pharmaceutical (Allergan, Pfizer, Perrigo), medical devices (Medtronic, Stryker, Boston Scientific) and others who have valuable patents (Eaton, Ingersol Rand).

In addition, non-US multinationals tend to have "territorial tax" systems in their home country which apply much lower tax rates on foreign sourced income (to incentivise companies to stay home).[29][30] Prior to the 2017 US TCJA, the US was one of the last of 8 jurisdictions to operate a "worldwide tax" system which applied a single high rate of tax on all income.[77]

This is why the main foreign multinationals in Ireland are US multinationals from IP-heavy, industries.[78][21]

IDA Ireland notes that 80% of the 210,443 Irish employees in foreign-owned firms, are from US-based multinationals.[23][16]. The other foreign multinationals are UK corporate inversions that ceased from 2009 (Shire plc was the last in 2008), when the UK moved to a full "terroritial tax" system and reduced its CT rate to 19% (see U.K. transformation).[79][29][80] The rest are UK retailers selling to Ireland (Tesco plc).

There are no non-US/non-UK foreign multinationals in Ireland's top 50 companies by 2017 turnover, and only one by employees (No 41 German retailer, Lidl).[21]

| Rank (By Revenue) |

Company Name[21] |

Operational Base[81] |

Sector (if non-IRL)[21] |

Inversion (if non-IRL)[82] |

Revenue (2017 €bn)[21] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apple Ireland | technology | not inversion | 119.2 | |

| 2 | CRH | IRL | - | - | 27.6 |

| 3 | Medtronic plc | life sciences | 2015 inversion | 26.6 | |

| 4 | technology | not inversion | 26.3 | ||

| 5 | Microsoft | technology | not inversion | 18.5 | |

| 6 | Eaton | industrial | 2012 inversion | 16.5 | |

| 7 | DCC | IRL | - | - | 13.9 |

| 8 | Allergan Inc | life sciences | 2013 inversion | 12.9 | |

| 9 | technology | not inversion | 12.6 | ||

| 10 | Shire | life sciences | 2008 inversion | 12.4 | |

| 11 | Ingersoll-Rand | industrial | 2001 inversion | 11.5 | |

| 12 | Dell Ireland | technology | not inversion | 10.3 | |

| 13 | Oracle | technology | not inversion | 8.8 | |

| 14 | Smurfit Kappa | IRL | - | - | 8.6 |

| 15 | Ardagh Glass | IRL | - | - | 7.6 |

| 16 | Pfizer | life sciences | not inversion | 7.5 | |

| 17 | Ryanair | IRL | - | - | 6.6 |

| 18 | Kerry Group | IRL | - | - | 6.4 |

| 19 | Merck & Co | life sciences | not inversion | 6.1 | |

| 20 | Sandisk | technology | not inversion | 5.6 | |

| 21 | Boston Scientific | life sciences | not inversion | 5.0 | |

| 22 | Penneys | IRL | - | - | 4.4 |

| 23 | Total Produce | IRL | - | - | 4.3 |

| 24 | Perrigo | life sciences | 2013 inversion | 4.1 | |

| 25 | Experian | technology | 2007 inversion | 3.9 | |

| 26 | Musgrave | IRL | - | - | 3.7 |

| 27 | Kingspan | IRL | - | - | 3.7 |

| 28 | Dunnes Stores | IRL | - | - | 3.6 |

| 29 | Mallinckrodt Pharma | life sciences | 2013 inversion | 3.3 | |

| 30 | ESB | IRL | - | - | 3.2 |

| 31 | Alexion Pharma | life sciences | not inversion | 3.2 | |

| 32 | Grafton Group | IRL | - | - | 3.1 |

| 33 | VMware | technology | not inversion | 2.9 | |

| 34 | Abbott Laboratories | life sciences | not inversion | 2.9 | |

| 35 | ABP Food Group | IRL | - | - | 2.8 |

| 36 | Kingston Technology | technology | not inversion | 2.7 | |

| 37 | Greencore | IRL | - | - | 2.6 |

| 38 | Circle K Limited | IRL | - | - | 2.6 |

| 39 | Tesco Ireland | food retail | not inversion | 2.6 | |

| 40 | McKesson | life sciences | not inversion | 2.6 | |

| 41 | Peninsula Petroleum | IRL | - | - | 2.5 |

| 42 | Glanbia | IRL | - | - | 2.4 |

| 43 | Intel Ireland | technology | not inversion | 2.3 | |

| 44 | Gilead Sciences | life sciences | not inversion | 2.3 | |

| 45 | Adobe | technology | not inversion | 2.1 | |

| 46 | CMC Limited | IRL | - | - | 2.1 |

| 47 | Ornua Dairy | IRL | - | - | 2.1 |

| 48 | Baxter | life sciences | not inversion | 2.0 | |

| 49 | Paddy Power Betfair | IRL | - | - | 2.0 |

| 50 | Icon Plc | IRL | - | - | 1.9 |

| Total | 454.4 | ||||

From the above table:

- US-controlled firms are 25 of the top 50 and represent €317.8 billion of the €454.4 billion in total 2017 revenue (or 70%);

- UK-controlled firms are 3 of the top 50 and represent €18.9 billion of the €454.4 billion in total 2017 revenue (or 4%);

- Irish-controlled firms are 22 of the top 50 and represent €117.7 billion of the €454.4 billion in total 2017 revenue (or 26%);

- There are no other firms in the top 50 Irish companies from other jurisdictions.

Royalty payment schemes

Double Irish is an IP-based BEPS tool used by US corporations[83] (e.g. Apple, Google and Facebook) in Ireland, to get to effective tax rates <1% on non-US income.[37][38][39] As the conduit by which US corporations built offshore reserves of $1trn [84][85] the double Irish is the largest recorded corporate tax avoidance structure in economic history.[86]

IFSC PwC Partner, Feargal O'Rourke (son of Minister Mary O'Rourke, cousin of Finance Minister Brian Lenihan Jnr) is regarded as its "grand architect".[70][71][87][88]

From the mid-2000s, US multinationals increased use of the Irish double Irish tax scheme (see table for Apple's ASI, by 2014 was circa 20% of Irish GNI*).[89]

Royalty schemes are subject to the “relevant trade” and “relevant activities” criteria mentioned above (see “multinational job focus” above).

In 2015, after EU and OECD pressure,[90] the Irish Government shut-down the double Irish by preventing an Irish registered company to be tax resident elsewhere (i.e. IRL2). Existing double Irish structures could continue until 2020.[91] Despite this, US corporate activity in Ireland increased post shut-down.[92]

A new IP-based BEPS tool called the single malt structure has replaced the double Irish in 2015 (IRL2 is instead re-located to Malta, with the same effect).[93][94] It is contended that the Irish Government's June 2017 decision to opt out of Article 12 of the OECD Multilateral Convention[95] was to protect single malt.[92]

It was interesting that when [Member of European Parliament, MEP] Matt Carthy put that to the Minister's predecessor (Michael Noonan), his response was that this was very unpatriotic and he should wear the green jersey. That was the former Minister's response to the fact there is a major loophole, whether intentional or unintentional, in our tax code that has allowed large companies to continue to use the double Irish [the "single malt"].

Capital allowances schemes

Professor Jim Stewart,

Trinity College Dublin,

"MNE Tax Strategies in Ireland", 2016[97]

The 2009 Irish Finance Act, materially expanded the range of intangible assets (or IP), that can attract Irish "capital allowances" which are deductible against Irish taxable profits.[98][99] These "specified intangible assets"[100] cover more esoteric intangibles such as types of general rights, general know-how, general goodwill, and the right to use software.[66] It includes types of "internally developed" intangible assets and intangible assets purchased from "connected parties". The control is that they must be acceptable under GAAP (old 2004 Irish GAAP is accepted) and approved by an IFSC accounting firm.[98][99]

Irish IP rules are now so broad (further loosened under later Finance Acts), that many businesses can create large artificial internal group IP assets (which an IFSC accounting firm will help develop, value, move onshore, and sign-off on Irish GAAP audits), that can be amortized to generate an effective 0-3% Irish IP-tax rate.

"It is hard to imagine any business, under the current [Irish] IP regime, which could not generate substantial intangible assets under Irish GAAP that would be eligible for relief under [the Irish] capital allowances [for intangible assets scheme]." "This puts the attractive 2.5% Irish IP-tax rate within reach of almost any global business that relocates to Ireland."

— KPMG, "Intellectual Property Tax", 4 December 2017[101]

Instead of the double Irish arrangement, where IP assets are charged to Ireland from an offshore location (or Malta for single malt), the Irish subsidiary can now buy the IP assets, using an inter-company loan, and then write-off the full acquisition cost over a fixed period (the period is what is in the GAAP accounts), against Irish pre-tax profits to give a 0-3% effective CT rate[102][76][40][42] over the period (depending on cap relief being 80% or 100%[65]). As the "product cycle" of the business develops, new IP is created offshore, and then purchased by the Irish subsidiary, keeping the scheme going in perpetuity.

There is a "clawback" provision that if the multinational leaves Ireland within 5 years, all the capital allowances are repayable (for schemes started after 13 February 2013)[66][45]

Capital allowances for intangible assets IP-based BEPS tool is subject to the “relevant trade” and “relevant activities” criteria mentioned above (see “multinational job focus” above).[43][44]

Capital allowances for intangibles scheme is Ireland's leading IP-based BEPS tool, enabling a broad range of group "virtual assets", to be written off in internal group transactions, against Irish tax.

Accenture was the first major user of the scheme in 2009 on $7bn of IP.[103] When Apple, one of the largest users of Irish tax structuring arrangements in the world, was re-structuring its controversial Irish subsidiaries in January 2015 (from the EU Commission €13bn ruling, see above), it chose this Irish capital allowances tax scheme rather than use a double Irish tax scheme (which Apple could have legitimately done in January 2015).[24] Some commentators estimate that Apple onshored up to $300bn of IP (vs. Irish GNI* of €190bn) in 2015.[3]

Apple's wider post Q1 2015 BEPS tax structure in Ireland has been called "the Green Jersey" by the EU Parliament's GUE-NGL body and analysed in detail.[104][105] In June 2018, Ireland's The Sunday Business Post revealed that Microsoft is preparing to execute a similar BEPS transaction.[106] Because the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") accepts foreign capital allowances - both tangible and intangible - in it's GILTI calculation, it has ironically made the "Green Jersey" an even more powerful BEPS tool to U.S. corporations, who can now achieve effective U.S. tax rates of 0-3% by using it.

Distortion of GNI/GNP/GDP

.png)

The above royalty payment tax BEPS schemes distort Irish GDP, and the later versions also distort Irish GNP, and even Irish GNI.

By 2011, Ireland's ratio of GNI to GDP, had fallen to 80% (only Luxembourg was lower at 73%). The EU27 average is closer to 100% (see table).[107][20]

An EU Commission report showed that from 2010 to 2015, over 23% of Ireland's GDP was represented by untaxed multinational net royalty payments.[6]

Irish financial commentators note how difficult it is to draw comparisons with other economies.[20] The classic example is the comparison of Ireland's indebtedness (Public and Private) when expressed "per capita" versus when expressed "as % of GDP". On a 2017 "per capita" basis, Ireland is one of the most leveraged OECD countries (both on a Public Sector and on a Private Sector Debt basis). On a 2017 "% of GDP" basis, however, Ireland is deleveraging rapidly.[108][109][110][111]

However, capital allowances for intangible assets tax schemes have an even more profound effect on GNI/GNP/GDP, as the IP asset is brought into the Irish economy (i.e. the IP is fully front loaded) and present more like quasi-corporate tax inversions in the Irish National statistics (but again, without any real tax revenues).

Leprechaun economics

.png)

.jpg)

.jpeg)

The distortion of Irish GDP/GNP came to a climax when Apple restructured its controversial ASI subsidiary (which EU Commission had judged as receiving illegal Irish State aid) in January 2015, and brought it "onshore" to Ireland via a new capital allowances for intangible assets scheme.[24]

Apple's restructuring led to 2015 Irish economic growth rates of 26.3% (GDP) and 18.7% (GNP) respectively.[112]

This led to Irish and International riducle[113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120], and was labelled by Noble Prize economist Paul Krugman as leprechaun economics.[121]

Markets saw Finance Minister Michael Noonan "pay" €380m in additional annual EU GDP levies[122][123] (he had made Apple's 2015 new Irish capital allowance scheme free of Irish taxes in the 2015 Budget by lifting the cap to 100%),[65] to generate "artificial" increases in the Irish GDP, GNP and GNI economic statistics.

His predessor, Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe immediately closed the 2015 Budget loophole to ensure that capital allowances schemes would at least pay effective Irish corporate tax rates of 2-3% (by reducing the cap on relief back to 80% from Noonan's 100% level). However, he only applied this to new schemes.[65]

While financial markets had always been wary of Irish economic data, Noonan's actions severally damaged their confidence.[124]

Introduction of GNI*

In response to the collapse in confidence, the Governor of the Central Bank of Ireland, Philip R. Lane, convened a special steering group (Economic Statistics Review Group) to recommend new economic statistics that would better represent the true position of the Irish economy.

The result was the creation of a new metric, modified gross national income (or GNI* for short). The difference between GNI* and GNI due to having to deal with two problems (a) The retained earnings of re-domiciled firms in Ireland (where the earnings ultimately accrue to foreign investors), and (b) depreciation on foreign-owned capital assets located in Ireland, such as intellectual property (which inflate the size of Irish GDP, but again the benefits accrue to foreign investors).[125][126]

Post leprechaun economics, 2016 Irish GNI* (€190bn) is 30% below 2016 Irish GDP (€275bn) and Irish Debt/GNI* goes to 106% (Irish Debt/GDP was 73%).[32][33]

Given that pre leprechaun economics, Irish GNI (which is affected by the capital allowances for intangible assets scheme[35]), was more than 20% below Irish GDP, commentators expected post leprechaun economics, Irish GNI* would be circa 40% below Irish GDP.[35][34]

Even with GNI*, a level of "distortion" remains in Irish National Accounts (i.e. gap between GNI* and "true" GNI)[35] from US multinational tax schemes.

Effective tax rate (ETR)

Ireland's "headline" corporate tax rate is 12.5% but its effective tax rate (or ETR), appears lower. The Department of Finance produced a report in April 2014 quoting World Bank/PwC figures that Ireland's corporate ETR was 12.3%.[127] In December 2014, a panel of experts gave estimates of Irish corporate ETRs to the Committee on Finance Public Expenditure (Sec 2 page 13):[12] The results of the experts imply a "green jersey agenda".

- 11.1% Prof. Frank Barry Trinity College, Dublin (Devereaux methodology)

- 14.4% Mr. Gary Tobin Department of Finance (European Commission/ZEW)

- 12.5% Mr. Eamonn O’Dea Revenue Commissioners (Revenue Statistical Data)

- 12.4% Mr. Conor O’Brien KPMG (Revenue Statistical Data)

- 2.2%/3.8% Prof. Jim Stewart Trinity College, Dublin (US BEA Data)

Most of these ETRs disagree with the known Irish corporate ETRs from Ireland's largest companies, who use Irish royalty payment BEPS schemes (double Irish and single malt), to get Irish ETRs of <1% (note, some Irish foreign multinationals don't publish accounts, so it is not possible to see all ETRs). Examples being:

- Apple Inc <1% (largest Irish company,[21] by 2017 revenues)[37][128][129]

- Google <1% (3rd largest Irish company,[21] by 2017 revenues)[38][130][131][129]

- Facebook <1% (9th largest Irish company,[21] by 2017 revnues)[132][39][133]

- Oracle <1% (12th largest Irish company,[21] by 2017 revenues)[134]

In addition, the leading Irish International Financial Services Centre tax-focused corporate law firms (such as Matheson, and Maples and Calder), openly market Irish corporate ETRs as being circa 2.5% for the third Irish BEPS scheme (capital allowances for intangible assets, or IP-tax rate):[42][102][76][135]

Intellectual Property: The effective corporation tax rate can be reduced to as low as 2.5% for Irish companies whose trade involves the exploitation of intellectual property. The Irish IP regime is broad and applies to all types of IP. A generous scheme of capital allowances .... in Ireland offer significant incentives to companies who locate their activities in Ireland. A well-known global company [Accenture in 2009] recently moved the ownership and exploitation of an IP portfolio worth approximately $7 billion to Ireland.

Structure 1: The profits of the Irish company will typically be subject to the corporation tax rate of 12.5% if the company has the requisite level of substance to be considered trading. The tax depreciation and interest expense can reduce the effective rate of tax to a minimum of 2.5%.

Why Ireland: The tax deduction can be used to achieve an effective tax rate of 2.5% on profits from the exploitation of the IP purchased. Provided the IP is held for five years, a subsequent disposal of the IP will not result in a clawback.

This 2.5% IP-tax rate was the capital allowances for intangible assets scheme when the annual intangibles relief was capped at 80% giving a 2.5% effective rate (100-80% x 12.5% = 2.5%). In the 2015 Irish Budget, as Apple was restructuring its Irish subsidiaries, Minister Michael Noonan increased the cap for annual intangibles relief to 100%, giving an effective 0% IP-tax rate. In the subsequent 2017 Irish Budget, the cap was reduced back to 80% again, but only for new capital allowances for intangible assets schemes (i.e. Apple's scheme would stay at 100%), returning the effective Irish IP-tax rate to 2.5%.[65]

These ETRs of 0-3% for the largest Irish firms and the three main multinational tax schemes, knowing that foreign multinationals pay 80% of Irish corporate tax and the top 20 multinationals pay 50% of all Irish corporate tax,[17][61] seem to directly conflict with the official Irish ETR estimates of circa 12.5% (i.e. how can the Irish headline rate be paid in aggregate if the biggest Irish firms pay <3%).

The issue is that the Revenue Commissioners, and KPMG/PwC calculations, exclude income not considered taxable under the Irish corporate tax code (why their calculations are inherently self-fulfilling, at 12.5%). The example of Apple's, Apple Sales International (ASI), Ireland's largest company by some margin,[21] shows the level of disconnect this approach can create compared to the reality of Irish taxes avoided. The Revenue Commissioners did not include ASI in Apple's Irish tax calculation.[136] In contrast, when the EU Commission investigated ASI, they calculated an ETR for Apple in Ireland of 0.005%.[137]

The Commission's investigation concluded that Ireland granted illegal tax benefits to Apple, which enabled it to pay substantially less tax than other businesses over many years. In fact, this selective treatment allowed Apple to pay an effective corporate tax rate of 1 percent on its European profits in 2003 down to 0.005 percent in 2014.

Make no mistake: the headline rate is not what triggers tax evasion and aggressive tax planning. That comes from schemes that facilitate profit shifting.

When the US Bureau of Economic Analysis ("BEA") approach is used (it adds up all Irish incorporated companies, including ASI, regardless of Irish taxability), the 2013 Irish effective tax rate is 2.2%. This approach would capture Apple's 0.005% rate above. The BEA calculation of Ireland's effective tax rate has generated much debate and dispute, both in Ireland,[41][139][140] and in the international media.[40][141]

The Irish Government[142] and several Irish leading Irish economists[143] and Irish tax advisors (including the creator of the double Irish, PwC's Feargal O'Rourke[144]) claim that this is not a fair representation of Ireland's ETR rate as Ireland is only a "conduit" in cases like Apple. For example, not all of ASI's profits would be in Irish GDP/GNP (this would change in leprechaun economics). However, other tax specialists and financial commentators,[36] highlight that the point of the BEA calculation is that it captures the scale of U.S. tax avoidance that Ireland's corporate tax system facilitates.[145][40][146]

Applying a 12.5% rate in a tax code that shields most corporate profits from taxation, is indistinguishable from applying a near 0% rate in a normal tax code.

Apple isn’t in Ireland primarily for Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate. The goal of many U.S. multinational firms’ tax planning is globally untaxed profits, or something close to it. And Apple, it turns out, doesn’t pay that much tax in Ireland.

Many of the multinationals gathered at the Four Seasons [in Dublin, Ireland] that day pay far less than 12.5 percent tax, their accounts show. Ireland helps them do this by generously defining what profit it will tax, and what it will leave untouched.

Where as the BEA calculation focuses purely on U.S. multinationals in Ireland, a June 2018 report by the University of Berkley (Gabriel Zucman) and the University of Copenhagen, calculated the ETR of all foreign multinationls in Ireland to be circa 4%,[149] and that Ireland is the largest corporate tax haven in world (even exceeding the Caribbean).[150][151]Discussed in Corporate Tax Haven ETRs.

It is important to note that the most attractive aspect of [corporate] tax incentives offered by Ireland is not the [headline 12.5%] tax rate but the tax regime.

— Professor Jim Stewart, Trinity College Dublin, "Apple Tax Case and the Implications for Ireland" (28 June 2017)[152]

Corporate tax inversions

Ireland's advanced holding company regime makes it a destination for corporate tax inversions, a strategy in which a, mostly, US-based company, takes over an Irish-based company, and then shifts its legal place of incorporation overseas to Ireland, (but not its majority ownership, headquarters or executive management, who can stay in the US),[153] to avail of Ireland's low corporate tax rates.[154][155]

The US tax code prohibits a US company creating a new "legal" headquarters in Ireland, while leaving the "real" executives in the US, under US anti-avoidance tax rules. However, where the movement is part of an acquisition, it is allowed.[82] The US company can then permanently avoid US taxes on non-US income and, can also use Irish "multinational tax" strategies to reduce US taxes on US income.[156]

Of the 85 inversions of US corporations that have occurred since 1982, Ireland has been the most popular destination, attracting almost a quarter (or 21 inversions):[82]

- (7 remaining inversions in

Ireland's first US inversion was Tyco in 1997, however the last 5 years have been dominated by US pharmaceuticals:[82][155]

- 2016

.svg.png)

- 2016

.svg.png)

- 2015

.svg.png)

- 2014

.svg.png)

- 2014

.svg.png)

- 2013

.svg.png)

- 2013

.svg.png)

The largest existing Irish US inversions are (showing market cap in October 2015 and year of inversion):[157]

- 2013

.svg.png)

- 2015

.svg.png)

- 2009

.svg.png)

- 2012

.svg.png)

- 2013

.svg.png)

- 2001

.svg.png)

- 1997

.svg.png)

- 2014

.svg.png)

- 2000

.svg.png)

- 2011

.svg.png)

Ireland has also been a recipient of UK inversions, the last one being Shire Pharma in 2008,[158] until the UK moved to a "terrorital tax" system.[79][29][80]

Corporate tax inversions differ from the earlier tax schemes in that the corporate "legally" onshores to Ireland (it inflates GNP and GNI as well as GDP). The inversion will be accompanied by an Irish multinational tax scheme, like capital allowances for intangibles, to reduce the Irish headline 12.5% CT rate to circa 0-3%, as noted by major Irish law firm, Arthur Cox, re Accenture inversion in 2009.[103]

Intellectual Property: The effective corporation tax rate can be reduced to as low as 2.5% for Irish companies whose trade involves the exploitation of intellectual property. The Irish IP regime is broad and applies to all types of IP. A generous scheme of capital allowances .... in Ireland offer significant incentives to companies who locate their activities in Ireland. A well-known global company [Accenture in 2009] recently moved the ownership and exploitation of an IP portfolio worth approximately $7 billion to Ireland.

The Irish Central Statistics Office ("CSO") articulate the fact that inversions "artificially" inflate Ireland's national accounts, without paying Irish taxes.

Redomiciled PLCs in the Irish Balance of Payments: Conducting little or no real activity in Ireland, these companies hold substantial investments overseas. By locating their headquarters in Ireland, the profits of these PLC’s are paid to them in Ireland, even though under double taxation agreements their tax liability arises in other jurisdictions. These profit inflows are retained in Ireland with a corresponding outflow only arising when a dividend is paid to the foreign owner.

It is asserted that the threat of such inversions, is what led to the informal system of the US Government allowing US corporates to use Irish "multinational tax schemes", and looser "controlled foreign corporation" rules, to avoid all taxes on non-US income (given how high the traditional US corporate tax rate used to be).[160] It was the EU who forced the closure of the "double Irish", not the US.[161]

US inversions are controversial in the US because they lower US taxes.[155] In April 2016, the U.S. government announced new rules to reduce the economic incentives for inversions.[155] The changes in US policy caused a planned $160bn merger between the U.S. pharmaceutical company Pfizer and the Irish pharmaceutical company Allergan, the largest inversion in history, to be dropped.[162][163]

The Trump administration has so far kept the Obama era rules blocking further inversions in place.[164]

It is asserted that the new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 will reduce the driver for US inversions[165] and in particular the move to a territorial tax system[80] and an attractive low-tax IP taxation regime.[166][167] There is a belief that the TCJA could even attract inversions (and IP) back to the US (as similar rules did in the UK in 2009-2012[29]). However, the Irish (and the UK) ultra-low-tax schemes could still attract US corporate inversions.[168] For example, the TCJA's new GILTI regime enforces a minimum 10.5% tax rate on IP-heavy US corporates, whereas Apple and Google pay <1% on profits in Ireland.[37][38][39]

U.S. multinationals like Pfizer announced in Q1 2018, a post-TCJA global tax rate for 2019 of circa 17%, which is very similar to the circa 16% expected by past U.S. multinational Irish tax inversions, Eaton, Allergan, and Medtronic. This is the effect of Pfizer being able to use the new U.S. 13.125% FDII regime, as well as the new U.S. BEAT regime penalising non-U.S. multinationals (and past tax inversions) by taxing income leaving the U.S. to go to low-tax corporate tax havens like Ireland.[169]

“Now that corporate tax reform has passed, the advantages of being an inverted company are less obvious”

Section 110 company

An Irish Section 110 Special Purpose Vehicle ("SPV") is an Irish tax resident company, which qualifies under Section 110 of the Irish Taxes Consolidation Act 1997 (“TCA”), by virtue of restricting itself to only holding "qualifying assets", for a special tax regime that enables the SPV to attain full tax neutrality (i.e. the SPV pays no Irish corporate taxes). It is an emerging Irish Debt-based BEPS tool.

Section 110 was created to help International Financial Services Centre ("IFSC") legal and accounting firms compete for the administration of global securitisation deals. They are the core of the IFSC structured finance regime[170] and the largest SPVs in EU securitisation[171]. Section 110 SPVs have made the IFSC the 4th largest global shadow banking centre.[172] They pay no Irish taxes but contribute circa €100m annually to the Irish Economy from fees paid to IFSC legal and accounting firms.[173]

Section 110 SPVs have been the subject of controversy. In 2016, it was discovered that US distressed debt funds used Section 110 SPVs, structured by IFSC service firms[174], to avoid material Irish taxes[175][176][177] on domestic Irish activities, [178][179] while mezzanine funds were using them to lower clients corporate tax liability.[180][181] Academic studies in 2017 note that Irish Section 110 SPVs operate in a brass plate fashion[182] with little regulatory oversight from the Irish Revenue or Central Bank of Ireland[183], and have been attracting funds from undesirable activities.[184][185][186][187][188][189]

These abuses were discovered because Section 110 SPVs file public accounts with the Irish CRO. In 2018 Central Bank of Ireland overhauled the little-used L-QIAIF, so that is now offers the same tax avoidance benefits on Irish assets held via debt as Section 110 SPVs, but without having to file public accounts (discussed in Ireland as a tax haven).

QIAIFs and L-QIAIFs

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Central Bank of Ireland's Qualifying investor alternative investment fund ("QIAIF") regime is a regulatory classification established in 2013 for Ireland's five tax-free legal structures for holding alternative investment assets. While only one of the five QIAIF wrappers is an Irish company, which would fall under the Irish corporation tax code (e.g. the Variable Capital Investment Company, or "VCC"), the QIAIF range, and the ICAVs wrapper in particular, are integrated with Irish BEPS tools. QIAIFs, with Section 110 SPVs, have made Ireland the 4th largest shadow banking centre.[8]

The Irish QIAIF regime is exempt from all Irish taxes and duties (including VAT and withholding tax), and apart from the VCC wrapper, do not have to file public accounts with the Irish CRO. This has made the QIAIFs an important "backdoor" out of the Irish corporate tax system. The most favoured destination is to Sink OFC Luxembourg, which receives 50% of all outbound Irish foreign direct investment ("FDI).[7]

When the Section 110 SPV tax avoidance scandals surfaced in late 2016, it was due to financial journalists and Dail Eireann representatives scrutinising the Irish CRO public accounts of U.S. distressed firms. In November 2016 the Central Bank began to overhaul the L-QIAIF regime. In early 2018, the Central Bank re-released the L-QIAIF regime so that it could replicate the Section 110 SPV (e.g. closed end debt structures), but without needing to file public CRO accounts. In June 2018, the Central Bank announced that €55 billion of U.S. distressed debt assets had transferred out of Section 110 SPVs.[190]

It is expected that the Irish L-QIAIF will replace the Irish Section 110 SPV as Ireland's main Debt-based BEPS tool for U.S. multinationals in Ireland.

The ability of foreign institutions to use QIAIFs (and particularly the ICAV wrapper) to avoid all Irish taxes on Irish assets has been blamed for the bubble in Dublin commercial property (and, by implication, the Dublin housing crisis).[191][192] This risk was highlighted in 2014 when Central Bank of Ireland consulted the European Systemic Risk Board ("ESRB") after lobbying to expand the L-QIAIF regime.[193]

Knowledge development box

Ireland created the first OECD compliant Knowledge Development Box ("KDB"), in the 2015 Finance Act, to further support it's intellectual property BEPS regime.[45][194] The KDB behaves like a capital allowances for intangible assets scheme with a cap of 50% (i.e. similar to getting 50% relief against your capitalised IP (GAAP intangible asset), for an effective Irish tax rate of 6.25%). As with the capital allowances for intangible assets scheme, the KDB is limited to specific "qualifying assets", however, unlike capital allowances, these are quite narrowly defined by the 2015 Finance Act.[195][196]

The Irish KDB has started off with tight conditions on use to ensure full OECD compliance (and thus adherence to the OECD's "modified Nexus standard" for IP[197]), and therefore OECD support. This has drawn criticism from Irish professional advisory firms who feel that its use is limited to pharmaceutical (who have the most "Nexus" compliant patents/processes), and some niche sectors.[198][199].

It is expected that these conditions will be relaxed over the next decade through refinements of the 2015 Finance Act. This is a route taken by other Irish IP-based BEPS tools, such as:

- Double Irish - the old Irish concept of a different definition of Irish tax residence was embedded into the 1997 Taxes and Consolidation Act ("TCA"), but expanded in 1999-2003 Finance Acts.[200]

- Single Malt - the double Irish tax residence terminology around "management and control", but entered directly into specific bi-lateral tax treaties (Malta, UAE).[92]

- Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets - introduced in 1997 TCA but materially expanded in 2009 Finance Act,[45] and made tax-free in the 2015 Finance Act.[65]

- Section 110 SPVs - introduced in the 1997 TCA with strong Irish anti-avoidance and domestic abuse controls, which were eroded in 2003, 2008, 2011 Finance Acts (see Section 110 article).

- L-QIAIFs - introduced in 2013 with the new EU AIFMD regulations, but expanded in 2018 into a full Debt-based BEPS tool.

It is expected that the KDB terms will ultimately be brought into alignment with the broader capital allowances for intangible assets terms in the future.[201]

The US Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 could materially limit KDBs for US multinationals in Ireland as the new US TCJA GILTI tax regime overrides the Irish KDB tax rate of 6.5% and enforces a higher rate on foreign-based IP of US multinationals. US multinational IP, in an Irish KDB, would pay a minimum effective US tax rate of 10.5% (GILTI tax) plus 1.3% (20% in unrelieved KDB tax), which totals 11.8%.[202]

While this ETR of 11.8% is still below the US TCJA FDII IP-tax regime of 13.125%, in practice the higher expensing and tax relief provisions in the US, will make the effective FDII tax closer to 11-12%.[203]

Corporate tax haven

Ireland as a tax haven

Ireland is labelled a both a corporate tax haven, due to BEPS tools, and a traditional tax haven, due to QIAIFs. The topic is covered in more detail in Ireland as a tax haven, however, the main facts regarding Ireland's corporate tax haven status are:

- Ireland is noted as a tax haven on all academic tax haven lists (Hines 1994 2007 2010, Dharmapala 2006 2010, and Zucman 2015 2018), all main non-governmental tax haven lists (Tax Justice Network, ITEP, Oxfam), and several U.S. Congressional (2008 2015) and Senate (2013) investigations;

- As well as appearing on all established Corporate tax haven lists, Ireland also ranks prominently on all "proxy tests" including distorted GDP-per-capita;

- Noted tax haven academic Gabriel Zucman (et alia) estimated in June 2018 that Ireland is the largest global corporate tax haven, and larger than the aggregate Caribbean tax haven system, and that Ireland's aggregate effective tax rate on foreign corporates is 4%;[4][204][1]

- CORPNET (University of Amsterdam) identify Ireland as one of the five leading global Conduit OFCs who are at the nexus of corporate tax avoidance, and who traditional tax havens (e.g. Caribbean tax havens) increasingly rely on to source corporate tax avoidance flows;

- Tax haven investigators identify Ireland as showing signs of behaving like a captured state willing to foster and protect tax avoidance strategies, and using complex data protection and privacy laws (e.g. no public CRO accounts) to function as a tax haven while still maintaining OECD-compliance and transparency;

Ireland does not appear on the 2017 OECD list of tax havens; only Trinidad and Tobago is on the 2017 OECD list, and no OECD member has ever been listed. Ireland does not appear on the 2017 EU list of 17 tax havens, or the EU's list of 47 "greylist" tax havens; again, no EU-28 country has ever been listed by the EU.

This apparent divergence in views on Ireland as a tax haven has been explained by academic research (see "complex agendas") as being the result of political compromises in Washington arising from the traditional U.S. "worldwide" tax system, which the EU has been willing to accommodate. The EU's €13 billion fine imposed on Apple in 2016 for Irish tax avoidance over 2004-2014 (see next), as well as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 overhaul of the U.S. corporate tax system (also, see next), could change this picture and reduce OECD tolerance of Ireland as a tax haven.

Apple tax ruling

International awareness of Ireland's role in corporate tax avoidance escalated further when on 29 August 2016, after a two-year EU investigation, Margrethe Vestager of the European Commission announced Apple Inc. received undue tax benefits from Ireland. The Commission ordered Apple to pay €13 billion, plus interest, in unpaid Irish taxes for 2004 to 2014.[205] This is the biggest tax fine in history.[2]

The issue is Apple's unique variation of the double Irish tax system which, up to end 2014, it used to shield circa €110bn[206] of non-US profits from tax. Apple did not use the standard two Irish companies (as Google and other Irish-based US multinationals employ) but received rulings from the Irish Revenue that it could use one Irish company (mainly Apple Sales International ASI), split into two "branches". This was not a ruling given to other Irish-based US multinationals and is therefore charged as being illegal Irish State Aid.[207]

It was shown in 2018 that Apple's subsequent re-structuring of its Irish subsidiaries in January 2015 was the driver of the Irish leprechaun economics 2015 GDP growth. It additionally highlighted that Apple is now using the new Irish capital allowances for intangible assets arrangement[24] to avoid taxes on non-US profits. The manner in which Apple executed this new scheme could be subject to further EU challenge and fines of a similar magnitude (see further potential Apple litigation),[208] and EU Commission are now investigating.[209]

US-EU counter measures

Under pressure from the EU[161], Ireland was forced to close the double Irish in 2015 (it remains in place for existing Irish multinationals until 2020[91]). However, Ireland opted out of Article 12 of the OECD Multilateral Convention which allowed it to protect its replacement single malt system.[92] Ireland is still a strong supporter of the slow moving OECD tax reform process.[210]

In April 2016, the US government announced new rules to block US corporate tax inversions.[155] The changes in US policy caused a planned $160bn merger between the U.S. pharmaceutical company Pfizer and the Irish pharmaceutical company Allergan, the largest inversion in history, to be dropped.[162][163] The Trump administration has so far kept the Obama era rules blocking further inversions in place.[164]

The EU Commission's August 2016 ruling against Apple in Ireland was also seen as an attempt to curb perceived abuses by US technology firms of European taxation systems.[211] The Commission has been going through all Irish Revenue rulings to multinationals and more cases may ensue (they have mentioned 14 other rulings).[212][6]

Parts of the December 2017 US TCJA are targeted at Irish "multinational tax schemes".[213][214] The FDII rate gives US multinationals an "Irish type" low tax rate (13.125%) for their royalty payment schemes created from intellectual property. The GILTI rate ensures that Irish "multinational tax schemes" (with effective Irish corporate tax rates close to 0%), produce effective US tax rates at or above the FDII.[215][216] (it is not confirmed if the EU's proposed 3% digital tax (and effective tax rate of 10-15%) would even be eligible for relief against the 10.5% US GILTI tax, as it is a revenue-tax and not a profits-tax).[217]

The new US GILTI tax regime, which acts like an international alternative minimum tax for IP-heavy US multinationals, has led some to qualify the new US TCJA system as a quasi-territorial tax system.[218][219]

Before the 2017 TCJA, US multinationals, with the necessary required IP to use Irish multinational tax schemes, could achieve effective Irish tax rates of 0-3% versus 35% in the US. After the 2017 TCJA, these same multinationals can now use this IP to generate US effective tax rates, which net of additional US tax reliefs, are similar to what they will pay in Ireland post GILTI (circa 11-12%).[218][219]

The EU's 2018 "digital services tax"[220] targets Irish "multinational tax schemes" as used by US technology firms.[216][221] As with the US TCJA GILTI rate, the EU's DST is designed to "override" Ireland's tax structures and force a minimum level of EU tax on US technology firms.[217] The EU's proposed 3% revenue tax will translate into an effective 10-15% tax rate (depending on pre-tax margins of 20-30% for Apple, Google and Microsoft), and is expensible, so it will reduce net Irish tax.[222] The EU's Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base ("CCCTB"), would even more severely affect Ireland.[223][224][225]

Risks beyond 2020

.png)

Brad Setser & Cole Frank (Council on Foreign Relations)

A number of Irish "multinational tax schemes", and international counter-measures to combat them, come to a head in 2020:

- Double Irish scheme fully expires (although the single malt could replace it unless also addressed by the EU).[91]

- "Clawback" on capital allowances for intangible assets BEPS tools expire; especially Apple's massive scheme (5 years for schemes after 13 Feb 2013).[66][226]

- US TCJA GILTI penalty rate rises from 2020 to 2025; certain foreign taxes may not be eligible for relief giving effective Irish tax rates well above 13.125%.[227]

- EU "digital services tax" (DST) is timetabled for January 2020,[220] and its rate could be used as leverage to bring in the more substantive CCCTB tax reform.[223]

- Max Schrems "Europe vs Facebook" data protection case, could force Facebook (and Google), to move business back to the US (under US data laws).[228]

(Due to the EU's 2018 GDPR, Facebook is moving non-EU customers hosted in Ireland (1.5bn of Ireland's 1.9bn accounts), to the US).[31]

In response to concern about this, the Irish Government commissioned a study on the sustainability of its Corporate Tax System in 2016 by University College Cork economist Seamus Coffey[67][68][69] which recommended scaling back of some corporate tax incentive schemes (i.e. reducing capital allowances for intangible assets to an 80% cap so that an effective Irish Corporation tax rate of 2-3% is paid). He has warned on the concentration of the sources of Ireland's corporate tax.[229][230]

In 2015 there were a number of “balance-sheet relocations” with companies who had acquired IP while resident outside the country becoming Irish-resident. It is possible that companies holding IP for which capital allowances are currently being claimed could become non-resident and remove themselves from the charge to tax in Ireland. If they leave in this fashion there will be no transaction that triggers an exit tax liability.

— Seamus Coffey, "Intangibles, taxation and Ireland's contribution to the EU Budget", October 2017[231]

Other leading Irish tax experts such as PriceWaterhouseCoopers Ireland managing partner, Feargal O'Rourke, have also warned about the sustainability of Irish CT.[232]

"The losses to the US budget from corporate tax avoidance are now out of control. The US loses as much as $111 billion each year due to corporate tax dodging – and let’s be honest, Ireland is implicated in a significant amount of this." "This is arguably the biggest economic challenge facing Ireland over the next decade."

Yearly returns

The key trends in yearly CT revenue are:

- Foreign multinationals dominate, paying circa 80% of CT revenue (notwithstanding that there are large Irish players like CRH plc, Ryanair plc, and Kerry Group plc).

- Note that IDA Ireland claims that US firms represent circa 80% of foreign employees[23][16], implying that US firms are circa 64% of CT revenue.

- The leprechaun economics moment in 2015 where Apple caused a material lift in CT (see above)

- Post Apple, CT revenue as a % of Total Tax revenue is close to past peak of over 16%

- The concentration of the top 10 CT payers has risen materially post the crisis (Irish banks stopped paying CT and US multinationals grew).

| Calendar Year |

Corporation Tax Revenue |

Total Tax Revenue |

CT % of Total Tax Revenue |

Top 10 Payer % of CT[17] |

Foreign Payer % of CT[17] |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 4.16 | 27.93 | 14.9% | .. | .. | [233] (restated) |

| 2002 | 4.80 | 29.29 | 16.4% | .. | .. | [233] |

| 2003 | 5.16 | 32.10 | 16.1% | .. | .. | [234] |

| 2004 | 5.33 | 35.58 | 15.0% | .. | .. | [235] |

| 2005 | 5.49 | 39.25 | 14.0% | .. | .. | [236] |

| 2006 | 6.68 | 45.54 | 14.7% | 17% | .. | [237] |

| 2007 | 6.39 | 47.25 | 13.5% | 16% | .. | [238] |

| 2008 | 5.07 | 40.78 | 12.4% | 18% | .. | [239] |

| 2009 | 3.90 | 33.04 | 11.8% | 35% | .. | [240] |

| 2010 | 3.92 | 31.75 | 12.4% | 32% | circa 80% | [241] |

| 2011 | 3.52 | 34.02 | 10.3% | 39% | circa 80% | [242] |

| 2012 | 4.22 | 36.65 | 11.5% | 34% | circa 80% | [243] |

| 2013 | 4.27 | 37.81 | 11.3% | 36% | circa 80% | [244] |

| 2014 | 4.61 | 41.28 | 11.2% | 37% | circa 80% | [245] |

| 2015 | 6.87 | 45.13 | 15.2% | 41% | circa 80% | [17] |

| 2016 | 7.35 | 49.02 | 15.0% | 37% | circa 80% | [17] |

History

Ireland's corporate tax code has gone through distinct phases of development, from building a separate dentify from the British system, to most distinctively, post the creation of the Irish International Financial Services Centre ("IFSC") in 1987, becoming a "low tax" knowlegdge based (i.e. focus intgangible assets) multinational economy.[246] This has not been without controversy and complaint from both Ireland's EU partners[247][248][249], and also from the US (whose multinationals, for specific reasons, comprise almost all of the major foreign multinationals in Ireland).[250]

Post-independence under Cumann na nGaedheal

It was only with the acceptance of the Anglo-Irish Treaty by both the Dáil and British House of Commons in 1922 that the mechanisms of a truly independent state begin to emerge in the Irish Free State. In keeping with many other decisions of the newly independent state the Provisional Government and later the Free State government continued with the same practices and policies of the iriash administration with regard to corporate taxation.

This continuation meant that the British system of "corporate profits taxation" ("CPT") in addition to income tax on the profits of firms was kept. The CPT was a relatively new innovation in the United Kingdom and had only been introduced in the years after World War I, and was widely believed at the time to have been a temporary measure. However, the system of firms being taxed firstly through income taxed and then through the CPT was to remain until the late seventies and the introduction of Corporation Tax, which combined the income and corporation profits tax in one.

During the years of W. T. Cosgrave's governments, the principal aim with regard to fiscal policy was to reduce expenditure and follow that with similar reductions in taxation. This policy of tax reduction did not extend to the rate of the CPT, but companies did benefit from two particular measures of the Cosgrave government. Firstly, and probably the achievement of which the Cumann na nGaedheal administration was most proud, was the reduction by 50% in the rate of income tax from 6 shillings in the pound to 3 shillings. While this measure benefited all income earners, be they private individuals or incorporated companies, a number of adjustments in the Finance Acts, culminating in 1928, increased the allowance on which firms were not subject to taxation under the CPT. This allowance was increased from £500, the rate at the time of independence, to £10,000 in 1928. This measure was in part to compensate Irish firms for the continuation of the CPT after it has been abolished in the United Kingdom.

A measure which marked the last years of the Cumann na nGaedheal government, and one that was out of kilter with their general free trade policy, but which came primarily as a result of Fianna Fáil pressure over the 'protection' of Irish industry, was the introduction of a higher rate of CPT for foreign firms. This measure survived until 1948, when the Inter-Party government rescinded it, as many countries with which the government was attempting to come to double taxation treaties viewed it as discriminatory.

Fianna Fáil under Éamon de Valera

The near twenty years of Fianna Fáíl government between from 1931 to 1948, cannot be said to have been a time where much effort was expended on changing or analysing the taxation system of corporations. Indeed, only one policy sticks out during those year of Fianna Fáil rule; being the continued reduction in the level of the allowance on which firms were to be exempt from taxation under the CPT, from £10,000 when Cumman na nGaehael left office, to £5,000 in 1932 and finally to £2,500 in 1941. The impact of this can be seen in the increasing importance of CPT as a percentage of government revenue, rising from and less than 1% of tax revenue in the first decade of the Free State to 3.64% in the decade 1942–43 to 1951–52. This increase in revenue from the CPT was due to more firms being in the tax net, as well as the reduction in allowances. The increased tax net can be seen from the fact that between 1932–33 and 1938–39, the number of firms paying CPT increased by over 33%. One other aspect of the Fianna Fáil government which bears all the fingerprints of Seán Lemass, was the 1946 decision to allow mining companies to write off all capital expenditure against tax over five years.

Seán Lemass and an Irish tax system

The period between after the late 1950s and up to the mid-1970s can be viewed as a period of radical change in the evolution of the Irish Corporate Taxations system. The increasing realisation of the government that Ireland would be entering into an age of increasing free trade encouraged a number of reforms of the tax system. By the mid-1970s, a number of amendments, additions and changes had been made to the CPT, these included fifteen-year tax holidays for exporting firms, the decision by the government to allow full depreciation in 1971 and in 1973, and the Section 34 of the Finance Act, which allowed total tax relief in respect of royalties and other income from licenses patented in Ireland.

This period from c.1956 to c.1975, is probably the most influential on the evolution of the Irish corporate tax system and marked the development of an 'Irish' corporate tax system, rather than continuing with a version of the British model.

This period saw the creation of Corporation Tax, which combined the Capital Gains, Income and Corporation Profits Tax that firms previously had to pay. Future changes to the corporate tax system, such as the measures implemented by various governments over the last twenty years can be seen as a continuation of the policies of this period. The introduction in 1981 of the 10% tax on manufacturing was simply the easiest way to adjust to the demands of the EEC to abolish the export relief, which the EEC viewed as discriminatory. With the accession to the EEC, the advantages of this policy became increasingly obvious to both the Irish government and to foreign multi-nationals; by 1982 over 80% of companies who located in Ireland cited the taxation policy as the primary reason they did so.

Charles Haughey low-tax economy (1987-2009)

The Irish International Financial Services Centre ("IFSC") was created in Dubin in 1987 by Taoiseach Charles Haughey with an EU approved 10% special economic zone corporate tax rate for global financial firms within its 11-hectare site. The creation of the IFSC is often considered the birth of the Celtic Tiger and the driver of its first phase of growth in the 1990s.[11][10]

In response to EU pressure to phase out the 10% IFSC rate by the end 2005, the overall Irish corporation tax was reduced to 12.5% on trading income, from 32%, effectively turning the entire Irish country into an IFSC.[246] This gave the second boost to the Celtic Tiger from 2000 up until the Irish economic crisis in 2009.[251][12]

In the 1998 Budget (in December 1997) Finance Minister, Charlie McCreevy[246] introduced the legislation for a new regime of corporation tax that led to the introduction of the 12.5% rate of corporation tax for trading income from 1 January 2003. The legislation was contained in section 71 of the Finance Act 1999 and provided for a phased introduction of the 12.5% rate from 32% for the financial year 1998 to 12.5% commencing from 1 January 2003. A higher rate of corporation tax of 25% was introduced for passive income, income from a foreign trade and some development and mining activities. Manufacturing relief, effectively a 10% rate of corporation tax, was ended on 31 December 2002. For companies that were claiming this relief before 23 July 1998, it would still be available until 31 January 2010. The 10% rate for IFSC activities ended on 31 December 2005 and after this date, these companies moved to the 12.5% rate provided their trade qualified as an Irish trading activity.

The additional passing of the important Irish Taxes Consolidation Act, 1997 (“TCA”) by Charlie McCreevy[252] laid the foundation for the new vehicles and structures that would become used by IFSC law and accounting firms to help global multinationals use Ireland as a platform to avoid non-US taxes (and even the 12.5% Irish corporate tax rate). These vehicles would become famous as the Double Irish, Single Malt and the Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets tax arrangements. The Act also created the Irish Section 110 SPV, which would make the IFSC the largest securitisation location in the EU.[253]

Post crisis zero-tax economy (2009-)

The Irish financial crises created unprecedented forces in the Economy. Irish banks, the largest domestic corporate taxpayers, faced insolvency, while Irish public and private debt-to-GDP metrics approached the highest levels in the OECD. The Irish Government needed foreign capital to re-balance their overleveraged economy. Directly, and indirectly, they amended many Irish corporate tax structures from 2009-2015 to effectively make them "zero-tax" structures for foreign multinationals and foreign investors. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis ("BEA") "effective" Irish CT rate, fell to 2.5%.[18][12][37][38][39]

They materially expanded the capital allowances for intangible assets scheme in the 2009 Finance Act. This would encourage US multinationals to locate intellectual property assets in Ireland (as opposed to the Caribbean, as per the double Irish scheme), which would albeit artificially, raise Irish economic statistics to improve Ireland's "headline" Debt-to-GDP metric. They also indirectly, allowed US distressed debt funds to use the Irish Section 110 SPV to enable them to avoid Irish taxes on the circa €100bn of domestic Irish assets they bought from NAMA (and other financial institutions) from 2012-2016.

While these BEPS schemes were successful in capital, they had downsides. US multinational tax schemes lead to large distortions in Irish GNI/GNP/GDP statistics.[254] When Apple "onshored" their ASI subsidiary in January 2015, it caused Irish GDP to rise 26.3% in one quarter ("leprechaun economics"). Foreign multinationals were now 80% of corporate taxes, and concentrated in a smaller group.[17] In response, the Government introduced "modified GNI" (or GNI*) in 2017 (circa 30% below Irish GDP)[126], and a paired back of some multinational schemes to improve corporation tax sustainability.[67][68]

Ireland's BEPS tax strategy led it to become labelled as one of the top 5 global conduit OFCs, and has come under attack from the US[250] and the EU (Apple's largest tax fine in history)[255]. Under pressure from the EU,[90][91] Ireland closed down the double Irish in 2015, which was described as the largest tax avoidance scheme in history. However, Ireland replaced it with the new single malt system[93][94], and an expanded capital allowances scheme. More targeted responses have come in the form of the US 2017 TCJA (esp. FDII and GILTI rates), and the EU's 2018 impending Digital Services Tax.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 "Ireland is the world's biggest corporate 'tax haven', say academics". Irish Times. 13 June 2018.

New Gabriel Zucman study claims State shelters more multinational profits than the entire Caribbean

- 1 2 Foroohar, Rana (30 August 2016). "Apple vs. the E.U. Is the Biggest Tax Battle in History". TIME.com. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Tax Avoidance and the Irish Balance of Payments". Council on Foreign Relations. 25 April 2018.

- 1 2 Gabriel Zucman; Thomas Torslov; Ludvig Wier (June 2018). "The Missing Profits of Nations". University of Berkley. p. 31.

Appendix Table 2: Tax Havens

- ↑ "Ireland named as world's biggest tax haven". The Times U.K. 14 June 2018.

Research conducted by academics at the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Copenhagen estimated that foreign multinationals moved €90 billion of profits to Ireland in 2015 — more than all Caribbean countries combined.

- 1 2 3 4 "Europe points finger at Ireland over tax avoidance". Irish Times. 7 March 2018.

- 1 2 "Ireland:Selected Issues". International Monetary Fund. June 2018. p. 20.

Figure 3. Foreign Direct Investment - Over half of Irish outbound FDI is routed to Luxembourg

- 1 2 "Ireland has world's fourth-largest shadow banking sector, hosting €2.02 trillion of assets". Irish Independent. 18 March 2018.

- ↑ "Warning that Ireland faces huge economic threat over corporate tax reliance - Troika chief Mody says country won't be able to cope with changes to tax regime". Irish Independent. 9 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Milestones of the IFSC". Finance Dublin. 2003.

- 1 2 "Dermot Desmond on the IFSC past and future". Finance Dublin. 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Report on Ireland's Relationship with Global Corporate Taxation Architecture" (PDF). Department of Finance. 2014.

- ↑ "Tax Strategy Group: Irish Corporate Taxation" (PDF). October 2011. p. 3.

- 1 2 "Fintan O'Toole: US taxpayers growing tired of Ireland's one big idea". Irish Times. 16 April 2016.

- 1 2 "IRELAND Trade and Statistical Note 2017" (PDF). OECD. 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "IDA Ireland Competitiveness". IDA Ireland. March 2018.