Kosančićev Venac

| Kosančićev Venac Косанчићев Венац | |

|---|---|

| Urban neighbourhood | |

| |

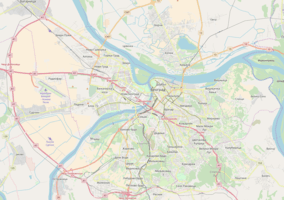

Kosančićev Venac Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°49′03″N 20°27′05″E / 44.8175°N 20.4514°ECoordinates: 44°49′03″N 20°27′05″E / 44.8175°N 20.4514°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Stari Grad |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Kosančićev Venac (Serbian Cyrillic: Косанчићев Венац) is an urban neighborhood of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is located in Belgrade's municipality of Stari Grad.

Location

Kosančićev Venac is located along the elbow-shaped street of the same name,700 m (2,300 ft) west of downtown Belgrade (Terazije). It developed on the western edge of the ending section of the ridge of Šumadija geological bar which extends from Terazijska Terasa "via" Obilićev Venac to Kalemegdan, which is a continuation of Kosančićev Venac and overlooks the Sava port on the Sava river, the northernmost section of the neighborhood of Savamala. On southeast it borders the neighborhood of Zeleni Venac.[1][2]

History

The neighborhood is built on the location of an Ancient Roman necropolis.[3]

Kosančićev Venac is the oldest section of Belgrade outside the walls of the Kalemegdan fortress, "the oldest neighborhood in Belgrade".[3] From this point the new Serbian town, as opposed to the old Turkish one in the fortress, began expanding from 1830 along the right bank of the Sava into Savamala. Princess Ljubica's Residence was built in 1831, Cathedral Church of St. Michael the Archangel in 1840, Hotel "Staro zdanje", kafana ?, Hotel "Kragujevac" and Metropolitan seat. The greatest effect on the economic prosperity and architectural shaping of Kosančićev venac had the vicinity of the Sava port which was the major hub of the international trade in Serbia at the time. Đumrukana, the custom house in Savamala, was built in 1835 and the neighborhood's section towards it was built as the wide plateau with open storage facilities. In the area in Đumrukana's direction soon hotels, inns, stores and craft shops were built.[4]

At modern 8 Kralja Petra Street, the first post office in Serbia was open on 7 June [O.S. 25 May] 1840. Called Praviteljstvena Menzulana, it dispatched mail on Wednesday, Saturday and twice on Sunday.[5]

In 1867 Emilijan Josimović devised the regulation plan for Belgrade which also covered this area. Kosančićev Venac was projected as the beginning and one of three sections of the urban settlement which will connect Terazije and Kalemegdan. All three sections are called venac (in this case: round, cyclic street, literally it is Serbian for wreath) and in 1872 named after three knights and heroes of the Battle of Kosovo: Kosančićev Venac, after Ivan Kosančić, Toplički Venac, after Milan Toplica and Obilićev Venac, after Miloš Obilić. The plan included covering the street with the rough cobblestone (kaldrma).[4]

At the beginning of the 20th century new building of the Patriarchal See of the Serbian Orthodox Church on the location of the old Metropolitan seat was constructed so as the representative building of the French embassy. Elementary School King Petar I was built in 1907. City light were introduced in that period and the tram grid expanded and kaldrma was partially replaced with the granite cobblestone and later, is some parts of the neighborhood, with the asphalt. In 1925, the National Library of Serbia relocated to Kosančićev venac.[4]

During the World War II, Kosančičev venac was heavily damaged, mostly by the German bombing of Belgrade on 6 April 1941. Destroyed buildings include the National Library, Đumrukana, Hotel "Kragujevac" and the newly built construction of the King Alexander Bridge suspension bridge.[4]

Features

Most recognizable characteristic of the neighborhood is the cobblestone, which still covers several streets in the area, though it has been badly damaged due to the frequent communal and infrastructural repairs. Because of the cobblestone and vintage appearance, Kosančićev Venac is nicknamed jewel, or pearl, of Belgrade.[6]

Several important early official buildings of Belgrade are located in the neighborhood:

- Princess Ljubica's Residence (built 1829-31; officially a museum, section of the Museum of Belgrade)

- Cathedral Church of St. Michael the Archangel (built 1837-40)

- Elementary School King Petar I (built 1905-07)

- Building of the Patriarchate (built 1932-35)

- Mika Alas's House (built 1910; house of Mihailo Petrović, popularly nicknamed Mika Alas, Serbian mathematician and inventor, who was born and died in it)

Other landmarks of the neighborhood include building nicknamed Home with the Pedigree and Trajković House with the bust of Ivan Kosančić, sculptured by Petar Ubavkić in 1895.[6]

Staro Zdanje

In 1843 in Dubrovačka Street (today Kralja Petra), reigning prince Mihajlo Obrenović built a large edifice, which became the first hotel in Belgrade, called Kod jelena ("Deer's"). Many criticized the move at the time, especially the cost and the size of the building, but it soon became the gathering point of the wealthiest citizens. They included Anastas Jovanović (first Serbian photographer), politician Ilija Garašanin, writer Ljubomir Nenadović, etc. Painter Stevan Todorović also stayed often, so prince gave him a room so that he could open the first artistic school and fencing school in Serbia. Colloquially, because of its size comparing to the other buildings at the time, the building was also referred to as Staro zdanje, or the "Big edifice". It was damaged in a fire in 1849 but was restored. Queen Natalie, as the sole heir of the dethroned Obrenović dynasty, sold the building to the state railroads company in 1903. The hotel operated in the building until that same year, when the Railroad Directory moved in. They moved out in 1938 when the building was demolished. In the 19th century, close to the hotel, at the modern 8 Kralja Petra Street, the first pharmacy in Belgrade was open.[7][8]

As an affluent, developing neighborhood, and with the proximity of the port, soon other hotels were built in the area. Best known included Nacional and Grand. Hotel Nacional was built across the southernmost extension of Kalamegdan, at the lowest section of the Pariska Street, where it meets the Great Staircase, which connects it to Savamala and the river bank. The Grand Hotel was built close to the cathedral church, but was later relocated to the Čika Ljubina Street, near the modern Faculty of Philosophy Plateau, across the Instituto Cervantes building.[9]

Lifting crane

There are still remnants of the big crane which was used to lift goods directly from the pier below to the elevated Kosančićev Venac.[6] Below the ridge on which Kosančićev Venac is located, there are numerous lagums, underground corridors, which were used as wine cellars and storages. They are located along the Karađorđeva Street, being dug into the hill so that goods could be stored directly after being loaded off the boats in the port. Entrances into the lagums are today buried and the corridors are largely forgotten.[10][11]

National Library

National Library of Serbia was located in the neighborhood from 1925. Building was constructed in the second half of the 19th century, it was owned by Milija Marković Raspop and artist Stevan Todorović held singing and painting classes in the house. Czech painter and émigré Kirilo Kutlik opened the Serbian drawing and painting school in the house in 1895. Industrialist Milan Vapa bought the house in 1910 and opened a paper mill. In 1921 Vapa sold the house to the Ministry of education specifically for the National Library. Project of the building's adaptation was conducted by Branko Tanazević and the new library was officially opened in 1925.[4] During the German bombing of Belgrade on 6 April 1941, it was heavily hit and then burned to the ground by the ensuing fire. Some 500,000 books perished, so as 1,500 Medieval Cyrillic manuscripts, charters and incunables dating from 12th to 17th century, 1,500 maps, 4,000 magazines, 1,800 newspapers, vast Turkish sources on Serbia during Ottoman rule, and personal correspondence of some of the most important people in cultural history of Serbia, like Vuk Karadžić, Đura Daničić, Pavel Šafarik and Lukijan Mušicki.[6][12] The site of the library was left in ruins with the commemorative plaque. In the 1970s, the archaeological digging was conducted on the library's location. Tens of thousands of charred books were dug and handed over to the National Library.[13] Since 2012, regular literary evenings are being held in the open, within the remnants of the building.[4]

Hôtel Palace

Hotel Palace is located in Topličin Venac, eastern extension of the neighborhood, next to the Park Proleće. The six-floor building was open on 12 May 1923 and at the time it was "the most beautiful and most modern hotel in the entire kingdom (Yugoslavia), and by the experts' judgment, it had no match in the entire Balkans". Architect and owner Leon Talvi (1880-1969)[14] said that, even though he was projecting a business object, he was guided by the aesthetic reasons. On the fifth floor there was an artistic gallery which consisted of 5 salons and a highly pricey collection made from the works of Italian, French, Russian and Yugoslav painters. The hotel had luxurious apartments, a theatre and cinema hall, dancing hall, three elevators, central heating, hot water, icehouse, garage, bus parking lot, etc. Pre-war hotel is described today as "Europe before European Union".[15]

After World War II began in 1939, but before it spread to Yugoslavia in 1941, Talvi, who was Jewish, sold Palace in 1940 to the Government of France and eventually emigrated to Israel. They adapted it into the French Cultural Center, which was to boost the cultural, scientific and technical cooperation between two countries. Right after the occupation, in April 1941 German Wehrmacht command moved in and all the highest officers lived in the apartments. Germans looted all the works of art from the hotel. From 1945 Palace was again a French Cultural Center, until 1948 when Yugoslav government traded the Union Palace building in Knez Mihailova Street, where the French Cultural Center is still located today, for Hotel Palace.[15]

Hotel was first ceded to the Finance ministry which used it to accommodate their clerks. Foreign ministry than took it over for the foreign guests, diplomats and visitors. Still, the hotel was on the verge of bankruptcy by 1957 when it became part of the Belgrade's School for Tourism and Hospitality, founded in 1938 and the largest one in Serbia. Hotel was revitalized and became especially popular among the athletes and served as sports' quarantine.[15] Today, Hotel Palace is a 4 star hotel with 86 units in total (33 one-bed rooms, 38 two-bed rooms, 15 apartments).[16]

Park of the Non-Aligned Countries

The southernmost section of the neighborhood is occupied by the Park of the Non-Aligned Countries. It is located on the plateau above the beginning section of the Branko's bridge. Main feature in the park is the 27 meters high white obelisk erected in 1961 to commemorate the First Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement, held in Belgrade in September 1961. Projected by Dušan Milenković, it consists of two triangular power line columns, and was placed as a temporary solution which was supposed to be replaced by the real monument. However, it was never replaced nor dismantled. Being white, there is a constants battle between the city's communal services who clean it and the vandals who spoil it with the graffiti. In 2005, the obelisk was covered with a gigantic condom replica as part of the anti-HIV monthly campaign. As the permit wasn't obtained by the authorities, it was quickly removed.[17]

Population

The local community Varoš Kapija, comprising partially the area of Kosančićev Venac had a population of 2,555 in 1981,[18] 2,274 in 1991[19] and 1,988 in 2002.[20] The municipality of Stari Grad later abolished the local communities.

Protection

The neighborhood was declared an archaeological site in 1964, being located within the boundaries of the ancient Singidunum.[4] In 1971 Kosančićev Venac was officially added to the Spatial Cultural-Historical Units of Great Importance list, and in 1979 was named a Monument of Culture, as "it is the area of the oldest Serbian settlement, the first developed administrative, cultural, spiritual and economic center of the city with specific ambient qualities". Apart from the central Kosančićev Venac street, protected area encompasses the streets of Srebrnička, Fruškogorska, Zadarska, Kralja Petra (lowere section), Pop-Lukina and Kneza Sime Markovića, and includes Cathedral Church, Princess Ljubica's Residence, Patriarchal See, Elementary School King Petar I and the Kafana ?.[6]

In popular culture

Due to its archaic look, Kosančićev Venac, was a location where several movies and TV series were filmed: Otpisani (1974–76), The Marathon Family (1982), Underground (1995).[6]

Reconstruction

In January 2007 the city government announced ambitious plans for the revitalization of Kosančićev Venac and the neighboring riverside section of Savamala. The first concern is the stabilization of the ground as the entire western slope of the ridge descending to the Sava is a mass wasting area (the leaning of the Cathedral Church is already visible from a distance). Kosančićev Venac is projected as the future cultural center of Belgrade. As it is not allowed to change the general shape of the neighborhood, Kosančićev Venac is declared a "zone of minor interventions" with several specific points of reconstruction. However, nothing has been done until 2016 when the new, revised plan of reconstruction and protection was adopted. The project covers 20 ha (49 acres) and mostly rehashes the former ideas:[4]

- Memorial center of the National Library of Serbia; a memorial center to commemorate the old location was to be built but not as a monument but as a "vigorous and modern cultural institution"; new plan gave a carte blanche to the architect Boris Podrecca.

- Đumrukana; an old custom house (Turkish: gümrük), as the very first administrative building built in the newly autonomous Serbia from the Turks, it was a symbol of the liberated country and also the location where the first theatre shows were organized in Belgrade in 1841-1842; only the foundations survive today, so the building will be reconstructed from scratch; it is also projected that Đumrukana will be an object of culture.

- A lookout point and a pedestrian pathway from downtown to the Sava bank, as today Kosančićev Venac has no direct approach to the river even though it is right above it. The only existing connections are two step-streets (Velike Stepenice and Male Stepenice, "Big steps" and "Small steps", respectively); natural lookout at the connection of the Kosančićev venac and Kralja Petra streets is considered one of the most beautiful in Belgrade.

- New representative cultural institution; will be built between the streets of Kosančićev venac and Karađorđeva; 2016 project specified it to be the City Gallery, dug into the ridge in the cascade construction.

- Existing Beton-Hala ("Concrete-Hall") in the port will be turned into a cultural and commercial center and a new green parking for tourist buses will be built too. It was later announced that works on Beton-Hala will begin in the autumn of 2007 and by spring 2008 it should be turned into the Museum of sports.

- 2016 project added reconstruction of the façades, streets and the Patriarchal See and the turning of the entire Kosančićev Venac area into the pedestrian zone with lots of trees.

First phase, which included streets and façades, began on 7 September 2016. The works were styled "historical" by the city authorities, though they indeed were overdue.[21] The phase was to be finished in February 2017, but as of May works were not even close to ending, with the streets being dug out, the buildings being covered in nylons and scaffolds and the entire neighborhood being noisy and covered in dust for months. Newspapers described Kosančićev venac as the "horror movie scenery", "ghostly" or looking like "during the World War II".[4][22] In June 2017, city urbanist Milutin Folić, announced that the façades will be finished in July, kaldrma only by the end of the year, the library will be revitalized in 2018 and when that is finished, the gallery will be built.[23] In August 2017 the deadline for façades was moved to November, to be finished concurrently with kaldrma, which is being arranged according to the plans from 1903.[24] However, as of February 2018, the troubled project is not yet finished, while architects denounced the quality of the works. The criticism include: frequent pauses and overall length of the works, disappearance of the original kaldrma from some parts of the street, general sloppiness and bad quality, bad leveling and height of the drains which cause formation of the ponds during the rain, several digging ups of the same sections, hodgepodge of the materials used, removal of some trees but not planting any new ones, low quality of the façades which are already cracking, etc.[25] The reconstruction was officially declared finished on 25 February 2018.[26] Architect and resident of Kosančićev Venac, Cecilija Bartok, criticized every aspect of the reconstruction (narrowing of the street, change of the materials, displacement of the sewage, incompetence of the workers) stating that the only work that really had to be done was reconstruction of the façades. She asserted that the entire neighborhood lost its authenticity and that it is devoid of its charm.[27]

In June 2017 a project of building the memorial park at the location of the ruined National library was announced. It should have two levels and will comprise the small amphitheater, black concrete monoliths which represent scattered books ("knowledge graveyard"), flower garden, ramps and stairways, an elevated small square ("piazzetta"), small fountain, benches and info tables with photos. The remaining foundations will be preserved and embedded into the new project which will be encircled with the wall of the béton brut with horizontal openings in it, to allow the spectators from the outside to see inside.[23]

In July 2017 Folić announced the reconstruction of the Karađorđeva street from the Beton-Hala to the Branko's Bridge, along the southern border of Kosančićev Venac. The works, projected by Podrecca, should start at the end of 2017 and will include: widening of the sidewalks, planting of the avenue, further reconstruction of the façades, relocation of the tramway closer to the river and placing them on the cobblestones and construction of the parking for the buses which pick up the tourists from the port.[28]

Tunnel

For decades, a 200 m (660 ft) long tunnel have been proposed in the western section of the neighborhood. It would actually follow the route of the Pariska Street, between the streets of Gračanička and Uzun Mirkova. This would allow for the ground level to be transformed into the plateau with a fountain, which would make an extension of the pedestrian zone of Knez Mihailova Street and create a continuous pedestrian zone from the Republic Square and Palace Albania to the Kalemegdan Park, the Belgrade Fortress and the rivers. It was envisioned by the first phase of the planned Belgrade Metro, 1973-1982.[29]

A bit longer version, from the Gračanička Street to monument of Rigas Feraios in the Tadeuša Košćuškog Street, resurfaced in 2012, in conjunction with the project of connecting the Savamala port and the fortress. In March 2012 it was announced that the construction will start by the end of the year. However, the planners from the 1970s version were against the execution, because they believed that the entire complex can exist only if there are already functioning subway lines, which as of 2018, are still not built. This way, the traffic problems won't be solved. Do to the price, general halt of the subway construction and constant changes in its routes, the project hasn't materialized yet.[29][30]

See also

References

- ↑ Tamara Marinković-Radošević (2007). Beograd - plan i vodič. Belgrade: Geokarta. ISBN 86-459-0006-8.

- ↑ Beograd - plan grada. Smedrevska Palanka: M@gic M@p. 2006. ISBN 86-83501-53-1.

- 1 2 Zdravko Zdravković (31 December 2017), "Kosančićev venac – stecište i inspiracija umetnika" [Kosančićev Venac - A gathering place and inspiration of the artists], Politika (in Serbian), p. 39

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Daliborka Mućibabić, Ana Vuković (14 May 2017). "Kosančićev venav kupa se u prašini" (in Serbian). Politika.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (7 June 2018). "На данашњи дан - Отворена прва пошта у Београду и Србији" [On this day - First post office in Belgrade and Serbia opened]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Branka Vasiljević (24 February 2015), "Kosančićev venac – potamneli biser prestoničke riznice", Politika (in Serbian), p. 16

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (25 January 2018). ""Čitanka" srpske istorije i kulture" [Reading book of Serbian history and culture]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 17.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (7–8 April 2018). "Razglednica koje više nema" [Postcards that is no more]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 22.

- ↑ Dragan Perić (2 September 2018). "Kada su svi putevi vodili u Beograd" [When all roads were leading to Belgrade]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1092 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Jelena Beoković, "Zaboravljeni život Savamale", Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ Nada Kovačević (2014), "Beograd ispod Beograda" [Belgrad beneath Belgrade], Politika (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Tri veka burne istorije Narodne Biblioteke Srbije" (in Serbian). Večernje Novosti. 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (21 January 2013), "Kosančićev venac pod teretom patine", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Leon Talvi at Geni

- 1 2 3 Miloš Lazić (8 April 2018). "Poznati hoteli - Svedoci istorije i mesta zabave" [Famous hotels - Witnesses of history and places of fun]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1071 (in Serbian). pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Hotel Palace

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (26 April 2017), "Obelisk pretvoren u podlogu za grafite", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 191. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

- ↑ Tanjug (7 September 2009). "Počela istorijska obnova Kosančićevog venca – prvo kaldrma oa drvoredi i fasade" (in Serbian). Blic.

- ↑ A.R. (18 February 2017). "Kao u Drugom svetskom ratu – Raskopine i blokovi na sve strane na Kosančićevom vencu" (in Serbian). Blic.

- 1 2 Ana Vuković, Daliborka Mučibabić (24 June 2017). "Temelji hrama knjige – mesto sećanja i susreta" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 15.

- ↑ "Radovi na Kosančićevom vencu biće gotovi do kraja novembra", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15, 23 August 2017

- ↑ Arch. Zoran Đorđević (14 February 2018). "Rekonstrukcija Kosančićev venca urađena traljavo" [Sloppy reconstruction of Kosančićev Venac]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 20.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (26 February 2018). "Отворен реконструисан Косанчићев венац" [Reconstructed Kosančićev Venac was open]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ Cecilija Bartok (14 May 2018). "Косанчићев венац изгубио аутентичност" [Kosančićev Venac lost authenticity]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 23.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (22 July 2017), "Karađorđeva ulica čeka majstore", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- 1 2 Daliborka Mučibabić, Dejan Aleksić (30 September 2018). "Нови саобраћајни тунели под водом, кроз брдо и центар града" [New traffic tunnels under water, through the hill and downtown]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (4 March 2012). "Ulice pešacima – tuneli saobraćaju" [Streets to pedestrians - tunnels for traffic]. Politika (in Serbian).

External links

- Old Town Above the Sava River (in English)

- Kosančićev Venac in New Apparel (in English)