Kalemegdan Park

| Kalemegdan Park | |

|---|---|

| Калемегдански парк | |

Kalemegdan Park | |

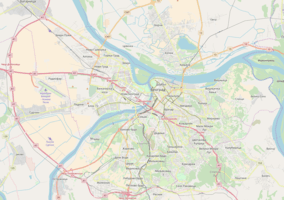

Location within Belgrade | |

| Location | Stari Grad, Belgrade |

| Coordinates | 44°49′21″N 20°27′11″E / 44.822593°N 20.453066°ECoordinates: 44°49′21″N 20°27′11″E / 44.822593°N 20.453066°E |

| Open | Open all year |

Kalemegdan Park (Serbian: Калемегдански парк, Kalemegdanski park) or simply Kalemegdan, is the largest park and the most important historical monument in Belgrade.[1] It is located on a 125-metre-high (410 ft) cliff, at the junction of the River Sava and the Danube. Its name is formed from the two Turkish words: "Kale" (meaning "fortress") and archaic word of Turkish origin "megdan" (meaning "battlefield").

Kalemegdan Park, split in two as the Great and Little Parks, was developed in the area that once was the town field. It provides places of rest and entertainment. Belgrade Fortress and Kalemegdan Park together represent a cultural monument of exceptional importance (from 1979), the area where various sport, cultural and arts events take place, for all generations of Belgraders and numerous visitors of the city.

History

The first works on arranging the town field Kalemegdan started in 1869, after the Turks completely withdrew from Belgrade and Serbia in 1867. Though not the oldest park in Belgrade, it is the one which is being continually groomed and attended the longest. The area of the town field was sort of a buffer zone between the fortress and the settlement outside of the Laudon trench, which separated the Turkish and the Serbian sections of Belgrade.[2][3] During March 1891, the pathways were cut through, and trees were planted; in 1903 the Small Staircase was built, based on the project of Jelisaveta Načić, the first woman architect in Serbia, while the Big Staircase, designed by architect Aleksandar Krstić, was built in 1928.

As of 2013, Kalemegdan Park covered an area of 53 ha (130 acres) and had 3,424 individual trees from 80 different tree species. Most of the trees were between 20 and 60 years old.[2]

Sections

Great Kalemegdan

Great Kalemegdan (Велики Калемегдански парк or Veliki Kalemegdanski Park) occupies the southern corner of the fortress, with geometrical promenades, a military museum, a museum of forestry and hunting, and the Monument of Gratitude to France.

Gondola lift

In August 2017 the construction of the gondola lift, which would connect Kalemegdan with the neighborhood of Ušće across the Sava, was announced by the city government for 2018.[4] Construction was confirmed in March 2018 when the idea of a pedestrian bridge was dropped after it has been described as "complicated" and "unstable". On the Kalemegdan side, the station will be dug into the hill, 1 m (3 ft 3 in) below the fortress' Sava Promenade. There is a cave 7 m (23 ft) below the projected station, so there is a possibility that the cave will be adapted for visitations and connected to the future gondola station by an elevator. On the Ušćе side, the starting point will be next to the Skate Park, across the Ušće Tower. The entire route is 1 km (0.62 mi) long, of which 300 m (980 ft) will be above the Sava river itself. Estimated cost is €10 million and duration of works 18 months, but it is still not known when the construction will begin.[5]

Little Kalemegdan

Little Kalemegdan (Мали Калемегдански парк or Mali Kalemegdanski park) occupies the area in the eastern section, which borders the urban section of Belgrade. Northern section of Little Kalemegdan Park is occupied by the Belgrade Zoo, opened in 1936. The Cvijeta Zuzorić Art Pavilion, built in 1928, is also located here.

Amusement park

An artificial pond, with small island and pedestrian bridges was formed in front of the zoo. It was destroyed during the bombing in World War II.[3] In 1958, an amusement park (luna park) was open on that same location. Its main attraction, the Ferris wheel, was installed in 1964. In Serbian called "Panorama", it was produced in the United Kingdom, then transported to Italy, while it arrived in Yugoslavia in the early 1950s. It was exhibited in almost all parts of the country, before it permanently settled in Kalemegdan. In 2013 there were only 6 of its kind in the world. Soon, it became a symbol of the park and Belgrade's counterpart of the Vienna's Wiener Riesenrad. When produced, it was the state of the art of its kind. It has a special mechanism which consists of a steel cable and a separate handle which allows for the manual bringing down of the gondolas, in case of power outage.[6]

Protection

On 29 February 1952 city adopted the "Decision on protection, adaptation and maintenance of the people's park of Kalemegdan" which set the borders of the protected areas as the rivers of Danube and Sava and the streets of Tadeuša Košćuškog and Pariska. In 1962, Belgrade's Institute for the cultural monuments protection expanded the zone to several blocks across the streets. Detailed plan on Kalemegdan from 1965 provided that, despite the immense archaeological value that lies beneath the fortress ground, basically only what was discovered by that time can be explored, restored or protected. That caused the problem both for the expansion of the park but even more for the further exploration of the fortress' underground. Best example is the Lower Town where neither the park fully developed nor the remains of the former port, which was located there, are visible.[7]

Proposed tunnel

For decades, a 200 m (660 ft) long tunnel have been proposed along the eastern section of the park. It would actually follow the route of the Pariska Street, between the streets of Gračanička and Uzun Mirkova. This would allow for the ground level to be transformed into the plateau with a fountain, which would make an extension of the pedestrian zone of Knez Mihailova and create a continuous pedestrian zone from the Republic Square and Palace Albania to the park, the fortress and the rivers. It was envisioned by the first phase of the planned Belgrade Metro, 1973-1982.[8]

A bit longer version, from the Gračanička Street to monument of Rigas Feraios in the Tadeuša Košćuškog Street, resurfaced in 2012, in conjunction with the project of connecting the Savamala port and the fortress. In March 2012 it was announced that the construction will start by the end of the year. However, the planners from the 1970s version were against the execution, because they believed that the entire complex can exist only if there are already functioning subway lines, which as of 2018, are still not built. This way, the traffic problems won't be solved. Do to the price, general halt of the subway construction and constant changes in its routes, the project hasn't materialized yet.[8][9]

Administration

While it was inhabited, Kalemegdan formed one of the quarters in the administrative division of Belgrade. It was called Grad, and translated in the foreign languages as "fortress". According to the censuses, it had a population of 2,219 in 1890, 2,281 in 1895, 2,777 in 1900, 2,396 in 1905 and 454 in 1910.[10]

With the neighboring residential area, Kalemegdan formed one of the local communities (mesna zajednica, a sub-municipal administrative unit), which had a population of 3,650 in 1981,[11] 3,392 in 1991[12] and 2,676 in 2002.[13] Municipality of Stari Grad, on whose territory Kalemegdan is located, later abolished local communities.

Gallery

|

References

- ↑ "Public enterprise", www.beogradskatvrdjava.co.rs, webpage: CO.rs Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine..

- 1 2 Branka Vasiljević (23 June 2013), "Prestonički parkovi - mladići od šezdeset leta", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Dragan Perić (25 March 2018). "Политикин времеплов - Било једном јеѕеро на Калемегдану" [Politika's chronicles - Once upon a time there was a lake in Kalemegdan]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1069 (in Serbian). p. 28.

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (25 August 2017), "Srpski Central park na Ušću" [Serbian Central Park in Ušće], Politika (in Serbian), p. 16

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (10 March 2018). "Gondolom od skejt parka do Kalemegdana" [From Skate Park to Kalemegdan by gondola lift]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Politika, March 2013, in Serbia

- ↑ Vladimir Bjelikov (September 2011), "U prilog Čodbrani beogradske tvrđave"", Politika (in Serbian)

- 1 2 Daliborka Mučibabić, Dejan Aleksić (30 September 2018). "Нови саобраћајни тунели под водом, кроз брдо и центар града" [New traffic tunnels under water, through the hill and downtown]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Daliborka Mučibabić (4 March 2012). "Ulice pešacima – tuneli saobraćaju" [Streets to pedestrians - tunnels for traffic]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ↑ Претходни резултати пописа становништва и домаће стоке у Краљевини Србији 31 декембра 1910 године, Књига V, стр. 10 [Preliminary results of the census of population and husbandry in Kingdom of Serbia on 31 December 1910, Vol. V, page 10]. Управа државне статистике, Београд (Administration of the state statistics, Belgrade). 1911.

- ↑ Osnovni skupovi stanovništva u zemlji – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1981, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file). 1983.

- ↑ Stanovništvo prema migracionim obeležjima – SFRJ, SR i SAP, opštine i mesne zajednice 31.03.1991, tabela 018. Savezni zavod za statistiku (txt file).

- ↑ Popis stanovništva po mesnim zajednicama, Saopštenje 40/2002, page 4. Zavod za informatiku i statistiku grada Beograda. 26 July 2002.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kalemegdan. |