Old Style and New Style dates

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) are terms sometimes used with dates to indicate that the calendar convention used at the time described is different from that in use at the time the document was being written. There were two calendar changes in Great Britain and its colonies, which may sometimes complicate matters: the first was to change the start of the year from Lady Day (25 March) to 1 January; the second was to discard the Julian calendar in favour of the Gregorian calendar.[2][3][4] Closely related is the custom of dual dating, where writers gave two consecutive years to reflect differences in the starting date of the year, or to include both the Julian and Gregorian dates.

Beginning in 1582, the Gregorian calendar replaced the Julian in Roman Catholic countries. This change was implemented subsequently in Protestant and Orthodox countries, usually at much later dates. In England and Wales, Ireland, and the British colonies, the change to the start of the year and the changeover from the Julian calendar occurred in 1752 under the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750. In Scotland, the legal start of the year had already been moved to 1 January (in 1600), but Scotland otherwise continued to use the Julian calendar until 1752.[5]

Thus, "New Style" can either refer to the start of year adjustment, or to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar.

Start of the year in the historical records of Britain and its colonies and possessions

.jpg)

When recording British history it is usual to use the dates recorded at the time of the event,[lower-alpha 1] with the year adjusted to start on 1 January. But the start of the Julian year was not always 1 January, and was altered at different times in different countries (see New Year's Day in the Julian calendar).

From 1155 to 1752, the civil or legal year in England began on 25 March (Lady Day)[6][7] so for example the execution of Charles I was recorded at the time in parliament as happening on 30 January 1648 (Old Style).[8] In newer English language texts this date is usually shown as "30 January 1649" (New Style).[2] The corresponding date in the Gregorian calendar is 9 February 1649, the date by which his contemporaries in some parts of continental Europe would have recorded his execution.

The O.S./N.S. designation is particularly relevant for dates which fall between the start of the "historical year" (1 January) and the official start date, where different. This was 25 March in England, Wales and the colonies until 1752.

During the years between the first introduction of the Gregorian calendar in continental Europe and its introduction in Britain, contemporary usage in England started to change.[4] In Britain 1 January was celebrated as the New Year festival,[9] but the "year starting 25th March was called the Civil or Legal Year, although the phrase Old Style was more commonly used."[4] To reduce misunderstandings about the date, it was normal in parish registers to place a new year heading after 24 March (for example "1661") and another heading at the end of the following December, "1661/62", a form of dual dating to indicate that in the following few weeks the year was 1661 Old Style but 1662 New Style.[10] Some more modern sources, often more academic ones, also use the "1661/62" style for the period between 1 January and 25 March for years before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in England. (See for example The History of Parliament).[11]

Scotland

Scotland had already partly made the change: its calendar year had begun on 1 January since 1600.[5]

Adoption of the Gregorian calendar

Through the enactment of the Irish Parliament's Calendar (New Style) Act, 1750,[12] and the British Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, Ireland, Great Britain and the British Empire (including much of what is now the eastern part of the United States) adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1752, by which time it was necessary to correct by 11 days. Wednesday, 2 September 1752, was followed by Thursday, 14 September 1752. Claims that rioters demanded "Give us our eleven days" grew out of a misinterpretation of a painting by William Hogarth.[13] The British tax year traditionally began on Lady Day (25 March) on the Julian calendar and this became 5 April, which was the "Old Style" equivalent.[14] A 12th skipped Julian leap day in 1800 changed its start to 6 April. It was not changed when a 13th Julian leap day was skipped in 1900, so the tax year in the United Kingdom still begins on 6 April.[15]

Adoption in the Americas

The European colonies of the Americas adopted the change when their mother countries did. In Alaska, the change took place after the United States purchased Alaska from Russia. Friday, 6 October 1867 was followed by Friday, 18 October. Instead of 12 days, only 11 were skipped, and the day of the week was repeated on successive days, because at the same time the International Date Line was moved, from following Alaska's eastern border with Canada to following its new western border, now with Russia.[16]

Transposition of historical event dates and possible date conflicts

Usually, the mapping of new dates onto old dates with a start of year adjustment works well with little confusion for events which happened before the introduction of the Gregorian calendar. For example, the Battle of Agincourt is universally known to have been fought on 25 October 1415, which is Saint Crispin's Day. But for the period between the first introduction of the Gregorian calendar on 15 October 1582 and its introduction in Britain on 14 September 1752, there can be considerable confusion between events in continental western Europe and in British domains. Events in continental western Europe are usually reported in English language histories as happening under the Gregorian calendar. For example, the Battle of Blenheim is always given as 13 August 1704. However confusion occurs when an event involves both. For example, William III of England arrived at Brixham in England on 5 November (Julian calendar), after setting sail from the Netherlands on 11 November (Gregorian calendar), in 1688.[17]

The Battle of the Boyne in Ireland took place a few months later on 1 July 1690 (Julian calendar). This maps to 11 July (Gregorian calendar), conveniently close to the Julian date of the subsequent [and more decisive] Battle of Aughrim on 12 July 1691. This latter battle was commemorated annually throughout the eighteenth century on 12 July,[18] following the usual historical convention of commemorating events of that period within Great Britain and Ireland by mapping the Julian date directly onto the modern Gregorian calendar date (as happens for example with Guy Fawkes Night on 5 November). The Battle of the Boyne was commemorated with smaller parades on 1 July. However, the two events were combined in the late 18th century,[18] and continue to be celebrated as "The Twelfth".

Because of the differences, English people and their correspondents often employed two dates, dual dating, more or less automatically. For this reason, letters concerning diplomacy and international trade sometimes bore both Julian and Gregorian dates to prevent confusion: for example, Sir William Boswell writing to Sir John Coke from The Hague dated a letter "12/22 Dec. 1635".[17] In his biography of Dr John Dee, The Queen's Conjurer, Benjamin Woolley surmises that because Dee fought unsuccessfully for England to embrace the 1583/84 date set for the change, "England remained outside the Gregorian system for a further 170 years, communications during that period customarily carrying two dates".[19] In contrast, Thomas Jefferson, who lived during the time that the British Isles and colonies eventually converted to the Gregorian calendar, instructed that his tombstone bear his date of birth using the Julian calendar (notated O.S. for Old Style) and his date of death using the Gregorian calendar.[20] At Jefferson's birth the difference was eleven days between the Julian and Gregorian calendars; thus his birthday of 2 April in the Julian calendar is 13 April in the Gregorian calendar. Similarly, George Washington is nowadays officially reported as having been born on 22 February 1732, rather than on 11 February 1731/32 (Julian calendar).[21]

There is some evidence that the calendar change was not easily accepted. Many British people continued to celebrate their holidays "Old Style" well into the 19th century, a practice that according to the author Karen Bellenir reveals a deep emotional resistance to calendar reform.[22]

Differences between Julian and Gregorian dates

The need for change arose from the realisation that the correct figure for the number of days in a year is not 365.25 (365 days 6 hours) as supposed by the Julian calendar but rather less: the Julian calendar has too many leap years. (See Tropical year#Mean tropical year current value for details). The consequence was that the basis for calculation of the date of Easter as decided in the fourth century had drifted from reality. The Gregorian calendar reform also dealt with the accumulated difference between these figures, between the years 325 and 1582 (1752 in the British Empire), by skipping 10 dates (11 in the case of Great Britain, including her colonies and Ireland) to restore the date of the vernal equinox to approximately March 21, the approximate date it occurred at the time of the First Council of Nicea in 325.

For a ready reckoner to assist in converting O.S. dates to N.S. and vice versa, see this table.

Anglophone usage describing events in other countries

It is common in English language publications to use the familiar Old Style and/or New Style terms when discussing events and personalities in other countries, especially with reference to the Russian Empire and the very-early Russian Soviet. For example, in the article "The October (November) Revolution" the Encyclopædia Britannica uses the format of "25 October (7 November, New Style)" to describe the date of the start of the revolution.[23]

When this usage is encountered, the reader should not assume that the British adoption date is intended, or that the 'start of year' change and the calendar system change were adopted concurrently, or even that religious adoption accompanied civil adoption. In the case of Eastern Europe, for example, all of these assumptions would be incorrect.

See also

Notes

- ↑ British official legal documents of the 16th and 17th centuries were usually dated by the regnal year of the monarch. As these commence on the day and date of the monarch's accession, they normally span two consecutive calendar years and have to be calculated accordingly, but the resultant dates should be unambiguous.

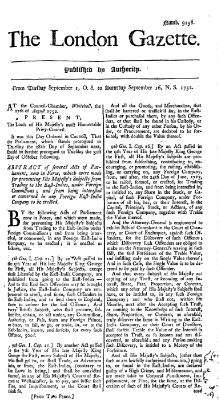

- ↑ Gazette 9198.

- 1 2 Death warrant of Charles I web page of the UK National Archives. A demonstration of New Style, meaning Julian calendar with a start of year adjustment.

- ↑ Stockton, J.R. Date Miscellany I: The Old and New Styles "The terms 'Old Style' and 'New Style' are now commonly used for both the 'Start of Year' and 'Leap Year' [(Gregorian calendar)] changes (England & Wales: both in 1752; Scotland: 1600, 1752). I believe that, properly and historically, the 'Styles' really refer only to the 'Start of Year' change (from March 25th to January 1); and that the 'Leap Year' change should be described as the change from Julian to Gregorian."

- 1 2 3 Spathaky, Mike Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian Calendar. "Before 1752, parish registers, in addition to a new year heading after 24th March showing, for example '1733', had another heading at the end of the following December indicating '1733/4'. This showed where the Historical Year 1734 started even though the Civil Year 1733 continued until 24th March. ... We as historians have no excuse for creating ambiguity and must keep to the notation described above in one of its forms. It is no good writing simply 20th January 1745, for a reader is left wondering whether we have used the Civil or the Historical Year. The date should either be written 20th January 1745 OS (if indeed it was Old Style) or as 20th January 1745/6. The hyphen (1745-6) is best avoided as it can be interpreted as indicating a period of time."

- 1 2 Steele 2000, p. 4.

- ↑ Nørby, Toke. The Perpetual Calendar: What about England? Version 29 February 2000.

- ↑ Gerard 1908.

- ↑ "House of Commons Journal Volume 8, 9 June 1660 (Regicides)". British History Online. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- ↑ Tuesday 31 December 1661, Pepys Diary "I sat down to end my journell for this year, .."

- ↑ Spathaky, Mike Old Style and New Style Dates and the change to the Gregorian Calendar. "An oblique stroke is by far the most usual indicator, but sometimes the alternative final figures of the year are written above and below a horizontal line, as in a fraction, thus: . Very occasionally a hyphen is used, as 1733-34."

- ↑ See for example this biographical entry: Lancaster, Henry (2010). "Chocke, Alexander II (1593/4-1625), of Shalbourne, Wilts.; later of Hungerford Park, Berks". In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1604-1629, ed. Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris, 2010 Available from Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Parliament of Ireland 1750.

- ↑ Poole 1995, pp. 95–139.

- ↑ Cheney & Jones 2000, p. 18

- ↑ Philip 1921, p. 24.

- ↑ Dershowitz, Nachum; Reingold, Edward M. (2008). Calendrical Calculations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 9780521885409.

- 1 2 Cheney & Jones 2000, p. 19.

- 1 2 Lenihan, Pádraig (2003). 1690 Battle of the Boyne. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. pp. 258–259. ISBN 0 7524 2597 8.

- ↑ Baker, John. "Why Bacon, Oxford and Other's Weren't Shakespeare". Archived from the original on 4 April 2005. ) uses this quote by Benjamin Woolley and cites The Queen's Conjurer, The Science and Magic of Dr. John Dee, Adviser to Queen Elizabeth I, page 173.

- ↑ "Old Style (O.S.)". monticello.org. June 1995. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ Engber, Daniel (18 January 2006). "What's Benjamin Franklin's Birthday?". Slate. Retrieved 8 February 2013. (Both Franklin's and Washington's confusing birth dates are clearly explained).

- ↑ Bellenir, Karen (2004). Religious Holidays and Calendars. Detroit: Omnigraphics. p. 33.

- ↑ EB online 2017.

References

- Cheney, C. R.; Jones, Michael, eds. (2000). A Handbook of Dates for Students of British History (PDF). Royal Historical Society Guides and Handbooks. 4 (Revised ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 17–20. ISBN 978-0-521-77095-8.

- "No. 9198". The London Gazette. 1 September 1752. p. 1.

- Parliament of Ireland (1750). "Calendar (New Style) Act, 1750". Government of Ireland. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- Philip, Alexander (1921). The Calendar: its history, structure and improvement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 24. ISBN 9781107640214.

- Poole, Robert (1995). "'Give us our eleven days!': calendar reform in eighteenth-century England". Past & Present. 149: 95–139.

- Russia: The October (November) Revolution (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2007.

- Steele, Duncan (2000). Marking Time: the epic quest to invent the perfect calendar. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780471404217.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Details of conversion for many countries

- Side-by-side Old style–New style reference

- Time to Take Note: The 1752 Calendar Change

- Calendar Converter Date converter for many systems, from John Walker

- Calendar converter to ancient Attic, Armenian, Coptic, Ethiopian by Academy of Episteme