Klamath Tribes

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~5000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

| |

| Languages | |

| English, maqlaqsyals | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Modoc, Yahooskin |

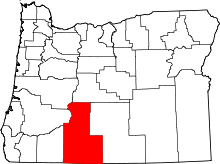

The Klamath Tribes, formerly the Klamath Indian Tribe of Oregon, are a federally recognized Native American Nation consisting of three Native American tribes who traditionally inhabited Southern Oregon and Northern California in the United States: the Klamath, Modoc, and Yahooskin. The tribal government is based in Chiloquin, Oregon.

History

Klamaths traditionally (and to this day) believe everything anyone needed to live was provided by the Creator in their rich land east of the Cascades. They saw success as a reward for virtuous striving and likewise as an assignment of spiritual favor; thus, elders counseled, "Work hard so that people will respect you."

For thousands of years, the Klamath people survived by their industriousness. When the months of long winter nights were upon them, they survived on prudent reserves from the abundant seasons. Toward the end of March, when supplies dwindled, large fish surged up the Williamson, Sprague, and Lost River. On the Sprague River, where Gmok'am'c first began the tradition, the Klamath's still celebrate the Return of C'waam Ceremony.

The Klamath bands were bound together by ties of loyalty and family. They lived along the Klamath Marsh, on the banks of Agency Lake, near the mouth of the Lower Williamson River, on Pelican Bay, beside the Link River, and in the uplands of the Sprague River Valley.

The most distinctive feature of pre-contact Klamath culture, compared with other Native American societies, was their individualistic rather than purely communal concept of wealth. Anthropologist Robert Spencer in "The Native Americans" [1] asserts that among the Klamaths, "A basic goal was wealth and the prestige derived from it ... The wealth quest was individual. Persons of 'good' reputation worked to produce and to enhance their social status." Historian Floy Pepper asserts that this set up Klamaths to do relatively well upon contact with white settlers, because "The Klamaths readily accepted certain aspects of the new culture. To work hard, to gain material possessions, to be practical were virtues of both worlds." [2]

Contact with white settlers

In 1826 Peter Skene Ogden, a fur trapper from the Hudson's Bay Company, was the first white man to leave footprints on Klamath lands. In 1832, the Hudson Bay trappers under John Work were in the Goose Lake Valley and their journals mentioned Hunter's Hot Springs. Work's expedition visited Warner Lakes and Lake Abert and camped at Crooked Creek in the Chandler Park area. They also reported being attacked by Indians.[3]

In 1838, Colonel J. J. Abert, a U.S. engineer, prepared a map that includes Warner Lakes and other natural features using information from the Hudson Bay trappers. In 1843, John C. Fremont led a party which named Christmas (Hart) Lake.[3]

1864 treaty begins Reservation Era

The Klamath Tribes ended hostilities with the invader and ceded more than 6 million acres of land in 1864. They did, however, retain rights to hunt, fish and gather in safety on the lands reserved for the people "in perpetuity" forever, which gave rise to modern litigation discussed below.

After signing the 1864 treaty, members were forcibly placed upon the Klamath Indian Reservation. At the time there was tension between the Klamath and the Modoc. A band of Modoc left the reservation to return to Northern California. The U.S. Army defeated them in the Modoc War (1872–73), and forcibly returned them to Oregon.[4] The Klamath Indian agency actually included three tribes: the Klamath, Modoc, and the Yahooskin Band of Snake Indians. In 1874, Oregon's legislature created Lake County, Oregon, which included the reservation lands (and from which Klamath County, Oregon was later separated).

Missionaries, settlers and ranchers followed, as the Klamath assimilated. One of the early Indian agents was Rev. Linus M. Nickerson, a former U.S. Army Chaplain in the American Civil War who had also worked for the Freedmen's Bureau in Fairfax, Virginia. In addition to conducting worship services, establishing a Sunday School and educating members of all three tribes (and members of other tribes they had adopted), Nickerson helped plan for improvements.

A Klamath Tribal Agency-sponsored sawmill was completed in 1870 and construction of Agency buildings began. By 1873, Tribal members were selling lumber to Fort Klamath and many private parties. By 1881 tribal members had already built a boarding school, an office building, many residences and agricultural outbuildings, miles of fencing and were working on a new police headquarters. By 1896 timber sales outside the reservation were estimated at a quarter of a million board feet. When a railroad was built in 1911, reservation timber became extremely valuable. The economy of Klamath County was sustained by it for decades.

Early in the reservation period, Klamath Tribal members demonstrated an eagerness to turn new economic opportunities to their advantage. Both men and women took advantage of the vocational training offered, and soon held a wide variety of skilled jobs within the reservation, as well as, the Fort Klamath military post, and in Linkville.

By 1881, Indian Agent Nickerson in his third annual report to his supervisors in Washington stated that a 50-pupil boarding school had been established, apprentices served at the sawmill, carpenter's shop and blacksmith shop, and a 10-member native police force led by the Klamath tribal chief and sub-chief kept order. However, he worried about superstitious practices, and particularly requested funds to set up a hospital because native doctors were losing control, and threatened to poison people. He also noted that tribal members were excellent workers and sought-after for work outside the reservation, and that a syphilis problem since contact with whites three decades earlier was being controlled. Nickerson also requested 300 yearling cattle and 20 breeder stallions to augment the ranching operations, as well as steel plows, but recognized that climate issues in the high desert would limit European type agriculture (the tribes cultivating some root crops and harvested aquatic plants in the swampy lake that gave the County its name during the summertime).[5] However, the irrigation system that Nickerson suggested in 1884 was only built 16 years later, after his death and a severe drought throughout the west.[6]

Before the reservation era, horses were considered an important form of wealth, so ranching and the ownership of cattle was easily accepted. Also, Nickerson on behalf of the Indian Agency initially leased some tribal lands to ranchers.[7] Today the cattle industry remains important economically.

Also, the Tribes had long-established trade networks, which led to successful freighting businesses. Nickerson requested sturdy wagons, and while some of those supplied proved inadequate, tribal operations used 80 wagons by 1881 (as well as 7 mowing machines and 5 sulky hay rakes and many smaller implements). By August 1889, 20 tribal teams worked year-round to supply both private and commercial needs in the rapidly growing county.

Klamath Termination Act

By the 1950s the Klamath Tribes were among the wealthiest Tribes in the United States. They owned (and judiciously managed for long-term yield) the largest remaining stand of Ponderosa pine in the west. Self-sufficient, the Klamath were the only tribes in the United States that paid for all federal, state and private services used by their members.

Congress ended federal supervision of the Klamath tribe in Oregon in 1954. The Klamath Termination Act (Public Law 587, enacted on August 13, 1954), embodied the U.S. Indian termination policy. Under this act, all federal supervision over Klamath lands, as well as federal aid provided to the Klamath because of their special status as Indians, ended.[8]

Termination of the Klamath tribe was part of a broader Federal Indian termination policy which persisted for about a decade after the Termination Act of 1953, which reflected the political climate of the era, ie fierce anti-communism.[9] Senator Arthur Watkins, one of the primer movers behind termination, reportedly "scoured the nation looking for tribes to terminate." [10]

In total, 113 Indian tribes were dissolved in the 1950s. There are 562 tribes recognized by the Federal Government in 2017; there may have been more in the 1950s, if some of them disintegrated after termination.

The Klamaths in particular were targeted for termination because they appeared to be prospering. A rarity among Native American groups, the Klamaths were financially self-sufficient, being the only tribe in the US to be funding the administrative costs of the Bureau of Indian Affairs through income tax contributions. By the 1940s, only 10% of Klamath families relied upon public welfare assistance.[11] An economist noted that "the Klamaths were never, since 1918, a 'burden' on taxpayers.".[12] This self-sufficiency was made possible by the richness of the reservation's natural timber resources. The unsuitability of the woodlands for conventional farming had meant that most of it had escaped the fate of being given to white settlers under the 1887 Allotment Act. Consequently, 862,622 valuable acres were retained as tribal property.

As testified to Congress in 1954, "The Klamath Tribe has been considered one of the most advanced Indian groups in the United States." [13] They did have an unusually high standard of living compared to other Native American tribes. But this was partly due to the sale of communal timber reserves which provided every Klamath with regular disbursements, that amounted to $800 a year by 1950.[14]

The Klamaths were also considered culturally suitable for termination. As testified to Congress by the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, "It is our belief ... these people have been largely integrated into all phases of the economic and social life of the area ... Their dress is modern, and there remains little vestige of religious or their traditional Indian customs ..." Klamath traditions also encouraged individualism and discouraged collectivism, the tribe having originally been a loose collection of autonomous tribelets which had only rarely, in their long history, united together in order to fight a common enemy. The 1956 Stanford report found that only half of Klamaths had a strong sense of identification with the tribe.[15]

US Congress also heard (but ultimately ignored) unfavourable information about the Klamaths' readiness for termination. The 1954 Termination Act provided for a period of evaluation before termination would take effect in 1961. This evaluation led the Bureau of Indian Affairs to accord the Klamaths a "questionable status" as to their readiness, even though it had been the BIA which had initially recommended the Klamaths for termination.[16] In 1957, Congress were told that in the 1953/54 school year, 40% of Klamath students had failed to move up to the next grade; that two-thirds of able-bodied males do little or no work; and that a majority of the Indian population had been arrested at some point in their lives.[17] Congress heard further testimony that although Klamaths had "shed the blanket" by abandoning outward Indian customs and dress, they hadn't "acquired the skills and attitudes necessary for the assumption of the responsibilities in a non-Indian society which they will be required to assume upon termination." The Klamath Education Program, designed to prepare Klamaths for termination, can only be viewed as hopelessly ineffective in their light of its own reports which reveal that up to 75% of Klamath Indians who enrolled for its vocational training programs failed to complete their courses.[18]

An unpopular Klamath leader, Wade Crawford, had proposed termination of his own tribe in 1945,[19] and tried to convince other Klamaths that termination would be in their interests, with some success among wealthier Klamaths who wanted more control over their own finances. He also exploited hostility towards the Bureau of Indian Affairs among people who resented its control over their affairs in general, claiming: "Politically we've been kicked around and exploited for years and we're sick of it. It has cost us millions of dollars and we don't want any more government control and any more bureaucracy."[20]

But ultimately Native American tribes were not consulted about termination. The fact that Klamaths in particular were not consulted was made clear by the testimony to Congress of Seldon Kirk, chairman of the Klamath General Council, in 1954: "We who represent and speak for the Klamath Indians really do not know what the Indians want themselves. We have never taken a vote on that question."

When they were finally invited to vote on the subject, they were not given the option of rejecting termination; they were only permitted to choose the way in which they were to be compensated for the loss of their reservation. Each tribal member was required to choose between remaining a member of the tribe, or withdrawing and receiving a monetary payment for the value of the individual share of tribal land.[21] Of the 2,133 Klamath tribal members at the time of termination, 1,660 (78%) decided to withdraw from the tribe and accept individual payments for land.[8] This resulted in a cash sum of US$43,000 per head being paid in 1961.

Those who stayed became members of a tribal management plan. This plan became a trust relationship between tribal members and the United States National Bank in Portland, Oregon.[22]

Termination of the Klamath Reservation, included three distinct but affiliated tribes. The Act defines the members as the "Klamath and Modoc Tribes and the Yahooskin Band of Snake Indians, and of the individual members thereof".[23] A portion of the Modoc Tribe had been taken as prisoners to Indian Territory in 1873 following the Modoc War in Oregon. In 1965, as a part of the US settlement with the Klamath reservation, a series of hearings were held from April to August. The hearings concluded without allowing the Oklahoma Modoc to be included in the rolls of the Klamath Tribe.[24]

Consequences of Termination

The immediate consequences of termination were predictably disastrous, although in the long run it is arguable that termination helped arrest the disintegration of the Klamath Tribe. Bitterness about their situation eventually encouraged Klamaths to stand up for their heritage and galvanized them into taking action to reverse termination, and achieve restoration of their tribe and re-establishment of the reservation. There is also evidence that the process of fighting for their heritage resulted in the Klamath sense of cultural identity becoming stronger than before termination. But a lot of hardship was suffered in the intervening years.

One problem was that 77% of the tribe, who had voted in 1958 to receive their assets in cash, collected a lump sum of $43,000 in 1961. The evidence is that most of the recipients did not handle the money wisely. By 1965, almost 40% admitted to having no funds left at all, and 50% had less than $10,000 remaining. [25] Tall stories about wasteful extravagance abounded, and some were true. One Klamath later told a reporter: "I blew it all on booze, women and cars." He had seen his money disappear in only seven months, $3,000 of it having been spent during just one night in a Portland bar.[26]

You can either blame the recipients of the money for their own behavior, or you can blame the government for being irresponsible in handing out such large sums of money to people who had mostly demonstrated a lack of consumer and investment skills, without giving them adequate preparation. As a County Commissioner speculated in 1966, "If you take the same number of blacks or whites who had not had experience handling money, and give them big checks, they will waste it, too." [27] Furthermore, their business naivety left many Klamaths open to economic exploitation, often being tricked out of large sums by unscrupulous merchants. As subsequent prosecutions divulged, many Klamaths were deceived into paying for goods at inflated prices or signing fraudulent contracts. To add insult to injury, upon prosecution, "it was not unusual for a Klamath Indian to be represented by an attorney who also represented the very party against whom the Klamath was seeking redress." [28]

Although local businesses initially benefited from this influx of money, once it dried up the feast was followed by a famine, as Klamaths became a drain upon Oregon's economy. Whereas prior to termination they had not been a burden on State finances, upon the withdrawal of their per capita payments a majority of Klamaths ended up on welfare and no longer contributed to the region's economic growth.

The adverse consequences of termination were not confined to the economy. In dissolving the Klamath reservation, termination deprived Klamaths of the final remaining part of their ancestral lands, which had been gradually taken from them since 1864. The process of environmental damage caused by Anglo settlement was accelerated as the reservation lands passed out of the control of Native Americans, who in general had far more respect for the natural landscape. Large hunts following termination quickly depleted game reserves, and wetlands were drained to the extent that only 10% of the original marshes still existed by 1992. Psychologically, Klamath cultural identity was adversely impacted by the loss of their reservation, which threatened one of the last vestiges of their traditional life: the Klamath physical and spiritual relationship with their lands.

As Klamaths increasingly were forced to operate or move outside of the former reservation area, culture shock was experienced by many, as they faced economic exploitation, racism, and discrimination in employment and housing. Further psychological damage was caused by the division of the tribe into three economic and legal units according to their voting actions in 1958: "remaining", "withdrawing" and "descendant" labels were applied, which inhibited both Tribal and family cohesiveness. [29] Moreover, the Klamaths were often subjected to ridicule from other Native American Tribes: "People made fun of us for being Klamath Indians. A lot of them said we were sell-outs and called us white people." [30] Termination had therefore struck a blow to the Klamath sense of identity, a fact emphasized when they were barred from participation in All-Indian rodeos because their tribe no longer had Federal Indian status.

In spite of experiencing financial, psychological and social hardships, Klamaths were compelled to cope with their traumas alone, since between 1961 and 1969 no Klamath institutions of support existed, and there was no political structure in operation until 1975.

As a result, termination meant that the tribe was cut off from services for education, health care, housing, and related resources. Decay set in, including poverty, alcoholism, high suicide rates, low educational achievement, disintegration of the family, poor housing, high dropout rates from school, disproportionate numbers in penal institutions, increased infant mortality, decreased life expectancy, and loss of identity.[31]

More to be added here about how this hardship triggered a growth in self-help organizations, political activism, and the fight for restoration.

Klamath Restoration Act of 1986

The western Modoc were restored to tribal status 15 May 1978, in an Act which reinstated the Modoc, Wyandotte, Peoria, and Ottawa Tribes of Oklahoma.[32] Almost a decade later, through the leadership and vision of the Klamath people, and the assistance of congressional leaders, the Klamath Restoration Act was adopted into law in 1986, reestablishing the Klamath as a sovereign state.[33] Although the land base was not returned, the Klamath Tribes were directed to compose a plan to regain economic self-sufficiency. Their Economic Self-sufficiency Plan reflects the Klamath Tribes' continued commitment to playing a pivotal role in the local economy.

Klamath Indian Reservation

The present-day Klamath Indian Reservation consists of twelve small non-contiguous parcels of land in Klamath County.[34] These fragments are generally located in and near the communities of Chiloquin and Klamath Falls. Their total land area is 1.248 square kilometres (308 acres). As is the case with many Native American tribes,[35] today few Klamath tribal members live on the reservation; the 2000 census reported only nine persons resided on its territory, five of whom were white people.[36]

Klamath Basin water rights

In 2001, an ongoing water rights dispute between the Klamath Tribes, Klamath Basin farmers, and fishermen along the Klamath River became national news. The Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement, under discussion since 2005, was ultimately signed into law in February 2010. To improve fishing for salmon and the quality of the salmon runs, the Klamath Tribes are pressing for dams to be demolished on the upper rivers, as they have reduced the salmon runs.

By signing the Treaty with the Klamath of 1864, 16 Stat. 707,[37] the Klamath tribe ceded 20 million acres (81,000 km2) of land but retained 2 million acres (8,100 km2) and the rights to fish, hunt, trap, and gather from the lands and waters as they have traditionally done for centuries.[38]

As part of an effort at assimilation, in 1954 the U.S. Congress had terminated the federal relationship with the Klamath Tribes, but stated in the Klamath Termination Act, "Nothing in this [Act] shall abrogate any water rights of the tribe and its members... Nothing in this [Act] shall abrogate any fishing rights or privileges of the tribe or the members thereof enjoyed under Federal treaty."[38]

The states of California and Oregon have both tried to challenge Klamath tribe's water rights, but have been rebuffed. Local farmers tried unsuccessfully to claim water rights in the 2001 cases, Klamath Water Users Association v. Patterson and Kandra v. United States but these were decided in favor of the Department of Interior's right to give precedence to tribal fishing in its management of water flows and rights in the Klamath Basin.[38] In 2002, U.S. District Judge Owen M. Panner ruled that the Klamath Tribes' right to water preceded that of non-tribal irrigators in the court case United States vs. Adair, originally filed in 1975.[39]

Demographics

There are over 5000 enrolled members in the Klamath Tribes,[40] with the population centered in Klamath County, Oregon. Most tribal lands were liquidated when Congress ended federal recognition in 1954 under its forced Indian termination policy. Some lands were restored when recognition was restored. The tribal administration currently offers services throughout Klamath county.

Economy

The Klamath Tribes opened the Kla-Mo-Ya Casino in Chiloquin, Oregon in 1997. It provides revenue which the tribe uses to support governance and investment for tribal benefit.

See also

References

- ↑ Robert. F. Spencer et. al, The Native Americans (New York: Harper and Row, 1977), p180 https://www.amazon.com/Native-Americans-Ethnology-Backgrounds-American/dp/0060463716

- ↑ Floy Pepper, Oregon Indian Treaties and the Law (Portland, Oregon: 1989), p63

- 1 2 "lakecountymuseum.com". lakecountymuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2007-08-18. Retrieved 2011-02-12.

- ↑ http://www.klamathtribes.org/history.html

- ↑ Oregon Indian agent report 1881 pp. 144-147 https://books.google.com/books?id=IvzPDTzgh9sC&pg=PA146&lpg=PA146&dq=linus+m+nickerson&source=bl&ots=larsmbDkxy&sig=E9o8fHY-sQr3IaW4T7npf9b3_mU&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjhh52kgNHRAhWIv1QKHSTvDpcQ6AEINjAI#v=onepage&q=linus%20m%20nickerson&f=false

- ↑ Robert H. Rudy and John Arthur Brown, Indians of the Pacific Northwest (University of Oklahoma Press 1988) p. 264 https://books.google.com/books?id=Ww8odDD86oAC&pg=PA264&lpg=PA264&dq=linus+m+nickerson&source=bl&ots=2BG8VrNBWq&sig=_UYKI-yR5KBM1k7zLpZVfda9KF4&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjhh52kgNHRAhWIv1QKHSTvDpcQ6AEIQzAO#v=onepage&q=linus%20m%20nickerson&f=false

- ↑ 1884 lease to Sprague at p. 754, available at https://books.google.com/books?id=wU9HAQAAIAAJ&pg=RA2-PA753&lpg=RA2-PA753&dq=linus+m+nickerson&source=bl&ots=38mUqzafCZ&sig=an6BksMwpeykFfk1gbFPS3plrRI&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjhh52kgNHRAhWIv1QKHSTvDpcQ6AEIODAJ#v=onepage&q=linus%20m%20nickerson&f=false

- 1 2 Charles E. KIMBALL et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. John D. CALLAHAN et al., Defendants-Appellees. United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, February 26, 1974. 493 F.2d 564

- ↑ http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/1511

- ↑ Kirke Kickingbird and Karen Ducheneaux, "One Hundred Million Acres (New York: Macmillan, 1973), p160 "https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/kirke-karen-ducheneaux-kickingbird/one-hundred-million-acres/

- ↑ Donald L. Fixico, "Termination and Relocation - Federal Indian Policy, 1945-1960 (Alberquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1969), p16

- ↑ William Thomas Trulove, "The Economic Impact of Federal Indian Policy: Incentives and Response of the Klamath Indians (unpublished University of Oregon PhD thesis, 1971), p16

- ↑ US Congress 1954a: 203-204

- ↑ Stanford Research Institute, "Preliminary Planning for Termination of Federal Control over the Klamath Indian Tribe" (Melno Park, California: Stanford Research Institute, 1956) p29

- ↑ Stanford Research Institute, "Preliminary Planning for Termination of Federal Control over the Klamath Indian Tribe" (Melno Park, California: Stanford Research Institute, 1956) p124

- ↑ Task Force Ten, "Terminated and Non federally recognized Indians - Final Report to the American Indian Policy Review Commission (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1976) p44

- ↑ US Congress, 1957a: 56-59

- ↑ Hiroto Zakoji, "Termination and the Klamath Indian Education Program, 1955-61 (Salem, Oregon: State Department of Education, 1961) p35

- ↑ Kirke Kickingbird and Karen Ducheneaux, "One Hundred Million Acres (New York: Macmillan, 1973), p169 "https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/kirke-karen-ducheneaux-kickingbird/one-hundred-million-acres/

- ↑ Task Force Ten, "Terminated and Non federally recognized Indians - Final Report to the American Indian Policy Review Commission" (Washington DC: US Government Printing Office, 1976) p45

- ↑ Wilkinson, Charles. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2005

- ↑ Hood, Susan, "The Termination of the Klamath Indian Tribe of Oregon", The American Society for Ethnohistory, 1972

- ↑ "25 U.S. Code § 564a - Definitions".

- ↑ http://soda.sou.edu/Data/Library1/020617a1.pdf

- ↑ Trulove (1971), p20

- ↑ The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), 11 July 1977, pB1

- ↑ The Oregonian (Portland, Oregon), 23 June 1966, p23

- ↑ Task Force, p59

- ↑ Kathleen Shaye Hill, "The Klamath Tribe: Beyond Termination", Indian Truth (Sept 1985), p5-6

- ↑ Oregon Public Broadcasting, My Land, Your Land, 1991

- ↑ Clements (2009), pp 47-62

- ↑ http://uscode.house.gov/statviewer.htm?volume=92&page=246

- ↑ "The Klamath Tribes -Termination". Archived from the original on 2015-03-21.

- ↑ The Klamath and Modoc Tribes and Yahooskin Band of Snake Indians v. The United States Finding of Fact, Oklahoma History Center, 1969 (retrieved 25 Nov 2009)

- ↑ "U.S. Society > Native Americans." US Diplomatic Mission to Germany. (retrieved 25 Nov 2009)

- ↑ "Klamath Reservation, Oregon". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2006-11-29.

- ↑ "Treaty with the Klamath, etc". Oklahoma State University. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- 1 2 3 "Klamath Tribes' Water Rights." Archived 2011-07-21 at the Wayback Machine. The Klamath Tribes. (retrieved 25 Nov 2009)

- ↑ "Judge affirms Klamath Tribes' water right of time immemorial", U.S. Water News Online, March 2002 (retrieved 25 Nov 2009)

- ↑ "The Klamath Tribes Today". The Klamath Tribes. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Klamath. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Modoc. |

- Klamath Tribes

- Guide to the Klamath Tribal Council papers (1933-1958) at the University of Oregon

- A Guide to the Yahooskin (Northern Paiute) Oral History Interviews, 96-24. Special Collections, University Libraries, University of Nevada, Reno.