Keir Hardie

| Keir Hardie | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Leader of the Labour Party | |

|

In office 17 January 1906 – 22 January 1908 | |

| Chief Whip |

David Shackleton Arthur Henderson George Henry Roberts |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Henderson |

| Member of Parliament for Merthyr Tydfil and Aberdare | |

|

In office 24 October 1900 – 26 September 1915 Serving with Edgar Rees Jones (1910–1915) | |

| Preceded by | William Pritchard Morgan |

| Succeeded by | Charles Stanton |

| Member of Parliament for West Ham South | |

|

In office 26 July 1892 – 7 August 1895 | |

| Preceded by | George Banes |

| Succeeded by | George Banes |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

15 August 1856 Newhouse, Lanarkshire, Scotland |

| Died |

26 September 1915 (aged 59) Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland |

| Nationality | British |

| Political party | Labour |

| Other political affiliations | Independent Labour Party |

| Spouse(s) | Lillias Balfour Wilson |

| Children | 4 |

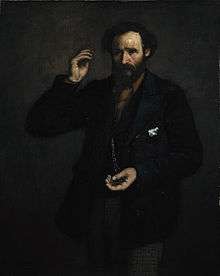

James Keir Hardie (15 August 1856 – 26 September 1915) was a Scottish socialist, politician, and trade unionist. He was the founder of the Labour Party, the first Leader of the Labour Party, and the first ever Labour Member of Parliament.

Hardie started work at the age of seven, but was rigorously educated at home by his parents, and later attended night school. Working in the mines, he soon became a full-time trade union organiser. His leadership of the failed Ayrshire miners’ strike of 1881 made such an impact on the mine-owners that they granted important concessions for fear of future industrial action.

Hardie was a dedicated Georgist for a number of years and a member of the Scottish Land Restoration League. It was "through the single tax" on land monopoly that Hardie gradually became a Fabian socialist. He reasoned that "whatever the idea may be, State socialism is necessary as a stage in the development of the ideal."[1][2]

Having won the parliamentary seat of West Ham South as an independent candidate in 1892, he helped to form the Independent Labour Party (ILP) the following year. In 1900 he helped to form the union-based Labour Representation Committee, soon renamed the Labour Party, with which the ILP later merged. Hardie was also a lay preacher and temperance campaigner, who supported votes for women, self-rule for India, home-rule for Scotland, and an end to segregation in South Africa. At the outbreak of World War I, he tried to organise a pacifist general strike, but died soon afterwards.

Early life

James Keir Hardie was born on 15 August 1856 in a two-roomed cottage on the western edge of Newhouse, North Lanarkshire, near Holytown, a small town close to Motherwell in Scotland. His mother, Mary Keir, was a domestic servant and his stepfather, David Hardie, was a ship's carpenter.[3] (He had little or no contact with his biological father, a miner from Lanarkshire named William Aitken.)[4] The growing family soon moved to the shipbuilding burgh of Govan near Glasgow (which wasn't incorporated into the city until 1912), where they made a life in a very difficult financial situation, with his stepfather attempting to maintain continuous employment in the shipyards rather than practising his trade at sea — never an easy proposition given the boom-and-bust cycle of the industry.[5]

Hardie's first job came at the very young age of seven, when he was put to work as a message boy for the Anchor Line Steamship Company. Formal schooling henceforth became impossible, but his parents spent evenings teaching him to read and write, skills which proved essential for future self-education.[6] A series of low-paying entry-level jobs followed for the boy, including work as an apprentice in a brass-fitting shop, work for a lithographer, employment in the shipyards heating rivets, and time spent as a message boy for a baker for which he earned four shillings and sixpence a week.[7]

A great lockout of the Clydeside shipworkers took place in which the unionised workers were sent home for a period of six months. With their main source of income terminated, the family was forced to sell all their possessions to pay for food, with Hardie's meagre earnings the only remaining source of income for the household. One sibling took ill and died in the miserable conditions which followed, while the pregnancy of his mother limited her own ability to work. Making matters worse, young James lost his job for turning up late on two occasions. In desperation, his stepfather returned to work at sea, while his mother moved from Glasgow to Newarthill, where his maternal grandmother still lived.[8]

At the age of ten years old, Hardie went to work in the mines as a "trapper" — opening and closing a door for a ten-hour shift in order to maintain the air supply for miners in a given section.[9] Hardie also began to attend night school in Holytown at this time.[10]

Hardie's stepfather returned from sea and went to work on a railway line being constructed between Edinburgh and Glasgow. When this job was completed, the family moved to the village of Quarter, South Lanarkshire, where Hardie went to work as a pony driver at the mines, later working his way into the pits as a hewer. He also worked for two years above ground in the quarries. By the time he was twenty, he had became a skilled practical miner.[11]

"Keir", as he was now called, longed for a life outside the mines. To that end, encouraged by his mother, he had learned to read and write in shorthand. He also began to associate with the Evangelical Union becoming a member of the Evangelical Union Church, Park Street, Hamilton – now the United Reformed Church, Hamilton (which also incorporates St. James' Congregational Church, attended by the young David Livingstone, the future famous missionary explorer) – and to participate in the Temperance movement.[12] Hardie's avocation of preaching put him before crowds of his fellows, helping him to learn the art of public speaking. Before long, Hardie was looked to by other miners as a logical chairman for their meetings and spokesman for their grievances. Mine owners began to see him as an agitator and in fairly short order, he and two younger brothers were blacklisted from working in the local mining industry.

Union leader

If Scottish mine owners had hoped to remove a potential labour agitator from their midst by blacklisting Hardie from work in the mines, their action proved to be a major miscalculation. The 23-year-old Keir Hardie moved seamlessly from the coal mines to union organisation work.

In May 1879, Scottish mine owners combined to force a reduction of wages,[13] which had the effect of spurring the demand for unionisation. Huge meetings were held weekly at Hamilton as mine workers joined together to vent their grievances. On 3 July 1879, Keir Hardie was appointed Corresponding Secretary of the miners, a post which gave him opportunity to get in touch with other representatives of the mine workers throughout southern Scotland.[14] Three weeks later, Hardie was chosen by the miners as their delegate to a National Conference of Miners to be held in Glasgow. He was appointed Miners' Agent in August 1879 and his new career as a trade union organiser and functionary was launched.[13]

On 16 October 1879, Hardie attended a National Conference of miners at Dunfermline, at which he was selected as National Secretary, a high-sounding title which actually preceded the establishment of a coherent national organisation by several years.[15] Hardie was active in the strike wave which swept the region in 1880, including a generalised strike of the mines of Lanarkshire that summer which lasted six weeks. The fledgling union had no money, but worked to gather foodstuffs for striking mine families, as Hardie and other union agents got local merchants to supply goods upon promise of future payment.[15] A soup kitchen was kept running in Hardie's home during the course of the strike, manned by his new wife, the former Lillie Wilson.

While the Lanarkshire mine strike was a failure, Hardie's energy and activity shone and he accepted a call from Ayrshire to relocate there to organise the local miners.[15] The young couple moved to the town of Cumnock, where Keir set to work organising a union of local miners, a process which occupied nearly a year.[16]

In August 1881, Ayrshire miners put forward the demand for a 10 percent increase in wages, a proposition summarily refused by the region's mine owners. Despite the lack of funds for strike pay, a stoppage was called and a 10-week shutdown of the region's mines ensued. This strike also was formally a failure, with miners returning to work before their demands had been met, but not long after the return wages were escalated across the board by the mine owners, fearful of future labour actions.[17]

To make ends meet, Hardie turned to journalism, starting to write for the local newspaper, the Cumnock News, a paper loyal to the pro-labour Liberal Party.[18]As part of the natural order of things, Hardie joined the Liberal Association, in which he was active. He also continued his temperance work as an active member of the local Good Templar's Lodge.[19]

In August 1886, Hardie's ongoing efforts to build a powerful union of Scottish miners were rewarded when there was formed the Ayrshire Miners Union. Hardie was named Organising Secretary of the new union, drawing a salary of £75 per year.[20]

In 1887, Hardie launched a new publication called The Miner.

Scottish Labour Party

Despite his early support of the Liberal Party, Hardie became disillusioned by William Ewart Gladstone's economic policies and began to feel that the Liberals would not advocate the interests of the working classes. Hardie concluded that the Liberal Party wanted the worker's votes without in return the radical reform he believed to be crucial – he stood for Parliament.

In April 1888, Hardie was an Independent Labour candidate at the Mid Lanarkshire by-election. He finished last but he was not deterred by this, and believed he would enjoy more success in the future. At a public meeting in Glasgow on 25 August 1888 the Scottish Labour Party (a different party from the 1994-created Scottish Labour Party) was founded, with Hardie becoming the party's first secretary. The party's president was Robert Bontine Cunninghame Graham, the first socialist MP, and later founder of the National Party of Scotland, forerunner to the Scottish National Party.

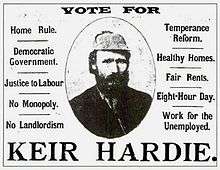

MP for West Ham South

Hardie was invited to stand in West Ham South in 1892, a working-class seat in Essex (now Greater London). The Liberals decided not to field a candidate, but at the same time not to offer Hardie any assistance. Competing against the Conservative Party candidate, Hardie won by 5,268 votes to 4,036. Upon taking his seat on 3 August 1892, Hardie refused to wear the "parliamentary uniform" of black frock coat, black silk top hat and starched wing collar that other working-class MPs wore. Instead, Hardie wore a plain tweed suit, a red tie and a deerstalker. Although the deerstalker hat was the correct and matching apparel for his suit, he was nevertheless lambasted in the press, and was accused of wearing a flat cap, headgear associated with the common working man – "cloth cap in Parliament". In Parliament, Hardie advocated a graduated income tax, free schooling, pensions, the abolition of the House of Lords and for women's right to vote.

Independent Labour Party

In 1893, Hardie and others formed the Independent Labour Party, an action that worried the Liberals, who were afraid that the ILP might, at some point in the future, win the working-class votes that they traditionally received.

Hardie hit the headlines in 1894, when after an explosion at the Albion colliery in Cilfynydd near Pontypridd which killed 251 miners, he asked that a message of condolence to the relatives of the victims be added to an address of congratulations on the birth of a royal heir (the future Edward VIII). The request was refused and Hardie made a speech attacking the monarchy, which almost predicted the nature of the future king's marriage which caused his abdication.

From his childhood onward this boy will be surrounded by sycophants and flatterers by the score—[Cries of ‘Oh, oh!’]—and will be taught to believe himself as of a superior creation. [Cries of ‘Oh, oh!’] A line will be drawn between him and the people whom he is to be called upon some day to reign over. In due course, following the precedent which has already been set, he will be sent on a tour round the world, and probably rumours of a morganatic alliance will follow—[Loud cries of ‘Oh, oh!’ and ‘Order!’]—and the end of it all will be that the country will be called upon to pay the bill. [Cries of Divide!][21]

This speech in the House of Commons was highly controversial and contributed to the loss of his seat in 1895.[22]

Labour Party

Hardie spent the next five years of his life building up the Labour movement and speaking at various public meetings; he was arrested at a woman's suffrage meeting in London, but the Home Secretary, concerned about arresting the leader of the ILP, ordered his release.

Keir Hardie, in his evidence to the 1899 House of Commons Select Committee on emigration and immigration, argued that the Scots resented immigrants greatly and that they would want a total immigration ban. When it was pointed out to him that more people left Scotland than entered it, he replied, "It would be much better for Scotland if those 1,500 were compelled to remain there and let the foreigners be kept out... Dr Johnson said God made Scotland for Scotchmen, and I would keep it so." According to Hardie, the Lithuanian migrant workers in the mining industry had "filthy habits", they lived off "garlic and oil", and they were carriers of "the Black Death".[23]

In 1900, Hardie organised a meeting of various trade unions and socialist groups and they agreed to form a Labour Representation Committee and so the Labour Party was born. Later that same year Hardie, representing Labour, was elected as the junior MP for the dual-member constituency of Merthyr Tydfil and Aberdare in the South Wales Valleys, which he would represent for the remainder of his life. Only one other Labour MP was elected that year, but from these small beginnings the party continued to grow, forming the first-ever Labour government in 1924.

Meanwhile, the Conservative Unionist government became deeply unpopular, and Liberal leader Henry Campbell-Bannerman was worried about possible vote-splitting across the Labour and Liberal parties in the next election. A deal was struck in 1903, which became known as the Lib-Lab pact of 1903 or Gladstone-MacDonald pact. It was engineered by Ramsay MacDonald and Liberal Chief Whip Herbert Gladstone: the Liberals would not stand against Labour in thirty constituencies in the next election, in order to avoid splitting the anti-Conservative vote.

In 1906, the LRC changed its name to the "Labour Party". That year, the newly established Liberal government of Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman called a General Election — resulting in a heavy defeat for the Conservative Party (then in opposition), and the landslide affirmation of the Liberals.

The 1906 general election result was one of the biggest landslide victories in British history: the Liberals swept the Conservatives (and their Liberal Unionist allies) out of what were regarded as safe seats. Conservative leader and former Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, lost his seat, Manchester East, on a swing of over 20 percent. What would later turn out to be even more significant was the election of 29 Labour MPs.

Later career

In 1908, Hardie resigned as leader of the Labour Party and was replaced by Arthur Henderson.[24] Hardie spent the rest of his life campaigning for votes for women and developing a closer relationship with Sylvia Pankhurst. His secretary Margaret Symons Travers was the first woman to speak in the Houses of Parliament when she tricked her way in on 13 October 1908.[25]

He also campaigned for self-rule for India and an end to segregation in South Africa. During a visit to the United States in 1909, his criticism of sectarianism among American radicals caused intensified debate regarding the American Socialist Party possibly joining with the unions in a labour party.

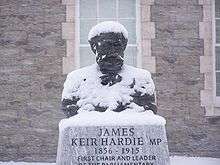

A pacifist, Hardie was appalled by the First World War and along with socialists in other countries he tried to organise an international general strike to stop the war. His stance was not popular, even within the Labour Party, but he continued to address anti-war demonstrations across the country and to support conscientious objectors. After the outbreak of war, on 4 August 1914, Hardie's spirited anti-war speeches often received opposition in the form of loud heckling. After a series of strokes Hardie died in hospital in Glasgow of Pneumonia at noon on 26 September 1915, aged 59[26]. His friend and fellow pacifist Thomas Evan Nicholas (Niclas y Glais) delivered the sermon at Hardie's memorial service at Aberdare, in his constituency.[27] He was cremated in Maryhill, Glasgow. A memorial stone in his honour is at Cumnock Cemetery Cumnock, Ayrshire, Scotland (pictured here).

Legacy

On 2 December 2006, a memorial bust of Keir Hardie was unveiled by Cynon Valley MP Ann Clwyd outside council offices in Aberdare (in his former constituency). The ceremony marked a centenary since the party's birth.

Hardie is still held in high esteem in his old home town of Holytown, where his childhood home is preserved for people to view, whilst the local sports centre was named in his own honour as "The Keir Hardie Sports Centre". Keir Hardie Memorial Primary School opened in 1956, named for him.[28] There are now 40 streets throughout Britain named after Hardie. Alan Morrison has, in turn, used the title Keir Hardie Street for his 2010 narrative long poem in which a fictitious, turn-of-the-century, working-class poet discovers a socialist utopia off the dreamt-up Sea-Green Line of the London Underground.[29]

One of the buildings at Swansea University is also named after him, while a main distributor road in Sunderland is named the Keir Hardie Way. The Ellen Wilkinson Estate in Wardley, East Gateshead (once in the Urban District of Felling, subsumed by Gateshead Metropolitan Borough in 1974) has Keir Hardie Avenue as its main street. Every other street is named after a pre-1960 Labour MP. The England footballer, Chris Waddle, lived in Number 1 Keir Hardie Avenue, Gateshead, between 1971 and 1983.

The Keir Hardie Estate in Canning Town (Newham, East London) is named after him as a legacy to his tenure as MP for West Ham South, Newham.[30] Keir Hardie Avenue in the town of Cleator Moor, Cumbria, has been named after him since 1942. Furthermore, an estate in the London Borough of Brent was also named after Hardie. Keir Hardie Crescent in Kilwinning in Scotland is named after him, as is a block of apartments in Little Thurrock. There is also a Keir Hardie Street in Greenock and a Keir Hardie Street in Methil, Fife, a predominantly Labour stronghold. Ty Keir Hardie, in his constituency town of Merthyr Tydfil, housed offices for Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council and adjoins the Civic Centre on Castle Street. In Merthyr Tydfil, there is also a Keir Hardie Estate with streets named after prominent early Independent Labour leaders such as Wallhead and Glasier.

In recognition of his work as a lay preacher, the Keir Hardie Methodist Church in London bears his name.

Labour founder Keir Hardie has been voted the party's "greatest hero" in a straw poll of delegates at the 2008 Labour conference in Manchester. Labour peer Lord Morgan, Ed Balls, David Blunkett and Fiona Mactaggart argued the case for four Labour figures at a Guardian fringe meeting at the Labour conference 2008 in Manchester, 23 September 2008.[31]

Keir Hardie's younger half-brothers David Hardie, George Hardie and sister-in-law Agnes Hardie all became Labour Party Members of Parliament after his death. His daughter Nan Hardie and her husband Emrys Hughes both became Provost of Cumnock; Hughes also became Labour Member of Parliament for South Ayrshire in 1946.

Biographer Kenneth O. Morgan has sketched Hardie's personality:

I found him a man who was not only an idealistic crusader, but a pragmatist, anxious to work with radical Liberals whose ideology he largely shared, subtle in building up the Labour alliance with the trade unions and the other socialist bodies, and supremely flexible in his political philosophy, a very generalised socialism based on a secularised Christianity rather than Marxism. 'Socialists,' he proclaimed, 'made war on a system not a class'....He was no economist and was ill-informed on many issues, but he had uniquely the charisma and vision that any radical movement needs.[32]

Keir Hardie Society

On 15 August 2010 (the 154th anniversary of Hardie's birth) the Keir Hardie Society was founded at Summerlee, Museum of Scottish Industrial Life.[33] The society aims to "keep alive the ideas and promote the life and work of Keir Hardie".[34] Amongst the co-founders was Cathy Jamieson, who at the time was the MSP for the constituency of Carrick, Cumnock and Doon Valley, which covers the area where Hardie lived most of his life. Scottish Labour leader Richard Leonard was the main founder of the society, along with Hugh Gaffney MP.

In other media

In August 2016, Jim Kenworth's play A Splotch of Red: Keir Hardie in West Ham was premiered at various venues in Newham, including Neighbours Hall in Canning Town at which Hardie spoke.[35] The play deals with Hardie's battle to win the constituency of West Ham South. It was directed by James Martin Charlton; Samuel Caseley played Keir Hardie.[36]

Works

- From Serfdom to Socialism (1907)

- Karl Marx: The Man and His Message (1910)

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Socialism in England: James Keir Hardie Declares that it is Capturing that Country". The San Francisco Call. 78 (117). 25 September 1895. p. 9. Retrieved 4 November 2014 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection. Hardie states, "I was a very enthusiastic single-taxer for a number of years."

- ↑ Edwards 1895, pp. 172–175.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 1.

- ↑ Morgan 2004.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 2.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 6.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 7.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 8.

- 1 2 Stewart 1925, p. 10.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, pp. 10–11.

- 1 2 3 Stewart 1925, p. 12.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 14.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 17.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 19.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Stewart 1925, p. 21.

- ↑ Paxman 2006, p. 58.

- ↑ Brocklehurst, Steven (26 September 2015). "Keir Hardie – The Man who Broke the Mould of British Politics". BBC News. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- ↑ Reid 1978, p. 122.

- ↑ Heppell 2010, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Elizabeth Crawford (2 September 2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge. pp. 669–670. ISBN 1-135-43402-6.

- ↑ Keir Hardie Death Certificate - Scotland's people

- ↑ "Ammanford, Carmarthenshire web site". Terrynorm.ic24.net. Retrieved 2013-02-10.

- ↑ "Keir Hardie Memorial Primary and Nursery". www.northlanarkshire.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ Morrison 2010, pp. 9–42.

- ↑ "James Kier Hardie, MP (1856-1915)". The Newham Story. 25 September 1915. Archived from the original on 12 January 2014. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Griffiths, Emma (22 September 2008). "Hardie is 'Greatest Labour Hero'". BBC News. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ Morgan 2015, pp. 89–90.

- ↑ "Society Launched to Honour Keir Hardie". Motherwell Times. Johnston Publishing. 26 August 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2013.

- ↑ "About the Society". Keir Hardie Society. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "A Splotch of Red - Keir Hardie in Westham". A Splotch of Red - Keir Hardie in Westham. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ↑ "West Ham United in a Socialist Vision". Morning Star. 24 August 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

Bibliography

- Edwards, Joseph, ed. (1895). The Labour Annual: A Year Book of Industrial Progress and Social Welfare. Manchester: Labour Press Society. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- Heppell, Timothy (2010). Choosing the Labour Leader: Labour Party Leadership Elections from Wilson to Brown. International Library of Political Studies. 48. London: Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-0-85771-850-1.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (2004). "Hardie, (James) Keir (1856–1915)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press (published 2011). doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33696.

- ——— (2015). Kenneth O. Morgan: My Histories. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-78316-323-6. JSTOR j.ctt17w8h53.

- Morrison, Alan (2010). Keir Hardie Street. Middlesbrough, England: Smokestack Books. ISBN 978-0-9560341-6-8.

- Paxman, Jeremy (2006). On Royalty. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-101222-3.

- Reid, Fred (1978). Keir Hardie: The Making of a Socialist. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-85664-624-9.

- Stewart, William (1925). J. Keir Hardie: A Biography (rev. ed.). London: Independent Labour Party Publication Department.

Further reading

- Benn, Caroline (1992). Keir Hardie. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-09-175343-6.

- Holman, Bob (2010). Keir Hardie: Labour's Greatest Hero?. Oxford: Lion Books. ISBN 978-0-7459-5354-0.

- Hughes, Emrys (1956). Keir Hardie. London: Allen & Unwin. ASIN B0006DBKFK.

- Jefferys, Kevin Jefferys, ed. (1999). Leading Labour: From Keir Hardie to Tony Blair. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-86064-453-5.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. (1975). Keir Hardie: Radical and Socialist. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-76886-9.

- ——— (1987). Labour People: Leaders and Lieutenants, Hardie to Kinnock. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285270-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keir Hardie. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Keir Hardie |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Keir Hardie |

- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by Keir Hardie

- J. Keir Hardie Biography, Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- J. Keir Hardie Internet Archive at Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- Rhondda Cynon Taff Online: Unveiling the Keir Hardie Bust. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

- Works by or about Keir Hardie at Internet Archive

- Works by Keir Hardie at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Scottish Labour Party, History

- Newspaper clippings about Keir Hardie in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)

| Parliament of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by George Banes |

Member of Parliament for West Ham South 1892–1895 |

Succeeded by George Banes |

| Preceded by William Pritchard Morgan David Alfred Thomas |

Member of Parliament for Merthyr Tydfil 1900–1915 With: David Alfred Thomas to 1910 Edgar Rees Jones from 1910 |

Succeeded by Charles Stanton Edgar Rees Jones |

| Political offices | ||

| New office | Chairman of the Independent Labour Party 1894–1900 |

Succeeded by John Bruce Glasier |

| Chairman of the British Labour Party 1906–1908 |

Succeeded by Arthur Henderson | |

| Preceded by William Crawford Anderson |

Chairman of the Independent Labour Party 1913–1914 |

Succeeded by Fred Jowett |

| Media offices | ||

| New office | Editor of the Labour Leader 1888–1904 |

Succeeded by John Bruce Glasier |

| Trade union offices | ||

| New office | Secretary of the Ayrshire Miners' Union 1886–1889 |

Succeeded by Peter Muir |