James Wilson

| James Wilson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office September 26, 1789 – August 21, 1798 | |

| Nominated by | George Washington |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Bushrod Washington |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

September 14, 1742 Carskerdo, Scotland, UK (now Ceres) |

| Died |

August 21, 1798 (aged 55) Edenton, North Carolina, U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse(s) |

Rachel Bird (1771–1786) Hannah Gray (1793–1798) |

| Education |

University of St Andrews University of Glasgow University of Edinburgh |

| Signature |

|

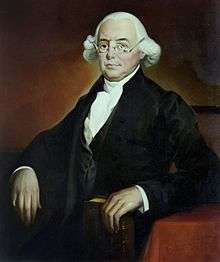

James Wilson (September 14, 1742 – August 21, 1798) was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States and a signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution. Wilson was elected twice to the Continental Congress, where he represented Pennsylvania, and was a major force in drafting the United States Constitution. A leading legal theorist, he was one of the six original justices appointed by George Washington to the Supreme Court of the United States.

Born near St Andrews, Scotland, Wilson immigrated to Philadelphia in 1766, becoming a teacher at the College of Philadelphia. After studying under John Dickinson, he set up a legal practice in Reading, Pennsylvania. He wrote a well received pamphlet arguing that Parliament's taxation of the Thirteen Colonies was illegitimate due to the colonies' lack of representation in Parliament. He was elected to the Continental Congress and served as president of the Illinois-Wabash Company, a land speculation company.

Wilson was a delegate to the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, and served on the Committee of Detail, which produced the first draft of the United States Constitution. Along with Roger Sherman, he proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted slaves as three-fifths of a person for the purposes of representation in the United States House of Representatives and the Electoral College. After the convention, he campaigned for the ratification of the document, and his "speech in the statehouse yard" was reprinted in newspapers throughout the country. He also played a major role in drafting the 1790 Pennsylvania Constitution.

In 1789, Wilson became one of the first Associate Justices of the Supreme Court. He also became a professor of law at the College of Philadelphia (which later became the University of Pennsylvania). Wilson suffered financial ruin from the Panic of 1796–97 and was briefly imprisoned in a debtors' prison on two occasions. He suffered a stroke and died in August 1798, becoming the first U.S. Supreme Court justice to die.

Early life and education

Wilson was one of seven children born into a Presbyterian farming family on September 14, 1742, near St. Andrews, Scotland, to William Wilson and Alison Landall. He studied at the Universities of St. Andrews, Glasgow and Edinburgh, but never obtained a degree.[1] While he was a student, he studied Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, including Francis Hutcheson, David Hume and Adam Smith.[2] He also played golf.[3] Imbued with the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment, he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in British America in 1765, carrying letters of introduction that enabled him to begin tutoring and then teaching at The Academy and College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). He petitioned there for a degree and was awarded an honorary Master of Arts several months later.[4] In 1790, the university awarded him the honorary degree of LL.D.[5]

While tutoring and teaching, Wilson began to read the law at the office of John Dickinson. He attained the bar in Philadelphia in 1767, and established a practice in Reading, Pennsylvania. His office was very successful and he earned a small fortune in a few years. By then he had a small farm near Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was handling cases in eight local counties, became a founding trustee of Dickinson College, and was lecturing at The Academy and College of Philadelphia. Wilson's religious beliefs evolved throughout his life, and have been the subject of some dispute, as there are writings from various points of his life from which it can be argued that he leaned towards Presbyterianism, Anglicanism, Thomism, or Deism, although it has been deemed likely that he eventually favored some form of Christianity.[6]

On November 5, 1771, he married Rachel Bird, daughter of William Bird and Bridget Hulings; they had six children together: Mary, William, Bird, James, Emily and Charles. Rachel died in 1786, and in 1793 he married Hannah Gray, daughter of Ellis Gray and Sarah D'Olbear; the marriage produced a son named Henry, who died at age three. After Wilson's death, Hannah married Thomas Bartlett, M.D.

Career

American Revolution

In 1774, Wilson published "Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament." In this pamphlet, Wilson argued that the Parliament had no authority to pass laws for the American colonies because the colonies had no representation in Parliament. It presented his views that all power derived from the people. Yet, he wrote that the people owed their allegiance to the English king: "A denial of the legislative authority of the British parliament over America is by no means inconsistent with that connexion, which ought to subsist between the mother country and her colonies." Scholars considered his work on par with the seminal works of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams of the same year. However, it was actually penned in 1768, perhaps the first cogent argument to be formulated against British dominance. Some see Wilson as a leading revolutionary while others see him as another reluctant, elite revolutionary reacting to the stream of events determined by the radicals on the ground.

In 1775, he was commissioned Colonel of the 4th Cumberland County Battalion[1] and rose to the rank of Brigadier General of the Pennsylvania State Militia.[7]

As a member of the Continental Congress in 1776, Wilson was a firm advocate for independence. Believing it was his duty to follow the wishes of his constituents, Wilson refused to vote until he had caucused his district. Only after he received more feedback did he vote for independence. While serving in the Congress, Wilson was clearly among the leaders in the formation of French policy. "If the positions he held and the frequency with which he appeared on committees concerned with Indian affairs are an index, he was until his departure from Congress in 1777 the most active and influential single delegate in laying down the general outline that governed the relations of Congress with the border tribes."[8]

Wilson also served from June 1776 on the Committee on Spies, along with Adams, Jefferson, John Rutledge, and Robert R. Livingston. They together defined treason.[9]

On October 4, 1779, the Fort Wilson Riot began. After the British had abandoned Philadelphia, Wilson successfully defended at trial 23 people from property seizure and exile by the radical government of Pennsylvania. A mob whipped up by liquor and the writings and speeches of Joseph Reed, president of Pennsylvania's Supreme Executive Council, marched on Congressman Wilson's home at Third and Walnut Streets. Wilson and 35 of his colleagues barricaded themselves in his home, later nicknamed Fort Wilson. In the fighting that ensued, six died, and 17 to 19 were wounded. The city's soldiers, the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry[10] and Baylor's 3rd Continental Light Dragoons, eventually intervened and rescued Wilson and his colleagues.[11] The rioters were pardoned and released by Joseph Reed.[12]

Wilson closely identified with the aristocratic and conservative republican groups, multiplied his business interests, and accelerated his land speculation. He became involved with the Illinois-Wabash Company during the War for Independence and was made its president in 1780.[13] He became the company's largest single investor, owning one and a half shares outright and two shares by proxy, totaling over 1,000,000 acres (400,000 ha) of land.[13] Wilson further expanded his land holdings by cofounding the Canna Company with Mark Bird, Robert Lettis Hooper, and William Bingham in order to sell land along the Susquehanna River in New York.[13] Additionally, Wilson individually bought huge quantities of land in Pennsylvania in 1784 and 56,000 acres (23,000 ha) of land in Virginia during the 1780s.[13] To round out his holdings, Wilson, in conjunction with Michael and Bernard Gratz, Levi Hollingsworth, Charles Willing, and Dorsey Pentecost purchased 321,000 acres (130,000 ha) of land south of the Ohio River.[13] He also took a position as Advocate General for France in America (1779–83), dealing with commercial and maritime matters, and legally defended Loyalists and their sympathizers. He held this post until his death in 1798.

Constitutional Convention

One of the most prominent lawyers of his time, Wilson is credited for being the most learned of the Framers of the Constitution. . A fellow delegate in the Constitutional Convention of 1787 in Philadelphia made the following assessment of James Wilson: "Government seems to have been his peculiar study, all the political institutions of the world he knows in detail, and can trace the causes and effects of every revolution from the earliest stages of the Grecian commonwealth down to the present time."[14]

Wilson's most lasting impact on the country came as a member of the Committee of Detail, which produced the first draft of the United States Constitution in 1787 (a year after the death of his first wife). He wanted senators and the president to be popularly elected. He also proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise at the convention, which made only three-fifths of the South's slave population total to be counted for purposes of distributing taxes and apportioning representation in the House and Electoral College. Along with James Madison, he was perhaps the best versed of the framers in the study of political economy. He understood clearly the central problem of dual sovereignty (nation and state) and held a vision of an almost limitless future for the United States. Wilson addressed the Convention 168 times.[15] A witness to Wilson’s performance during the convention, Dr. Benjamin Rush, called Wilson's mind "one blaze of light."[16] Madison and Wilson not only far outdistanced the others at the Convention as political theorists, they were also two of the closest allies in both the convention debates and ratification effort afterward.[17]

Though not in agreement with all parts of the final, necessarily compromised Constitution, Wilson stumped hard for its adoption, leading Pennsylvania, at its ratifying convention, to become the second state (behind Delaware) to accept the document.

Statehouse Yard speech

His October 6, 1787, "speech in the statehouse yard" (delivered in the courtyard behind Independence Hall) has been seen as particularly important in setting the terms of the ratification debate, both locally and nationally. It is second in influence behind The Federalist Papers. It was printed in newspapers and copies of the speech were distributed by George Washington to generate support for the ratification of the Constitution.[18][19]

In particular, it focused on the fact that there would be a popularly elected national government for the first time. He distinguished "three simple species of government" monarchy, aristocracy, and "a republic or democracy, where the people at large retain the supreme power, and act either collectively or by representation."[20] During the speech, Wilson also had harsh criticism for the proposed Bill of Rights. Powers over assembly, the press, search and seizure, and others covered in the Bill of Rights were, according to Wilson, not granted in the Enumerated Powers so therefore were unnecessary amendments.[21][22][23][24]

Wilson was later instrumental in the redrafting of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776, leading the group in favor of a new constitution, and entering into an agreement with William Findley (leader of the Constitutionalist Party) that limited the partisan feeling that had previously characterized Pennsylvanian politics.

Supreme Court career and final years

George Washington nominated Wilson to be an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court on September 24, 1789, after the court was organized under the Judiciary Act of 1789. The United States Senate confirmed his appointment on September 26, 1789, and Washington commissioned Wilson on September 29, 1789. Only nine cases were heard by the court from his appointment in 1789 until his death in 1798.

He became the first professor of law at the College of Philadelphia in 1790—only the second at any academic institution in the United States—in which he mostly ignored the practical matters of legal training. Like many of his educated contemporaries, he viewed the academic study of law as a branch of a general cultured education, rather than solely as a prelude to a profession.

Wilson broke off his first course of law lectures in April 1791 to attend to his duties as Supreme Court justice on circuit. He appears to have begun a second-year course in late 1791 or in early 1792 (by which time the College of Philadelphia had been merged into the University of Pennsylvania), but at some unrecorded point the lectures stopped again and were never resumed. They were not published (except for the first) until after his death, in an edition produced by his son, Bird Wilson, in 1804. The University of Pennsylvania Law School in Philadelphia officially traces its foundation to Wilson's lectures.

Wilson's last and final years were marked by financial failures. He assumed heavy debts investing in land that became liabilities with the onset of the Panic of 1796–1797. Of note was the failure in Pennsylvania with Theophilus Cazenove. In debt, Wilson was briefly imprisoned in a debtors' prison in Burlington, New Jersey. His son paid the debt, but Wilson went to North Carolina to escape other creditors. He was again briefly imprisoned, but continued his duties on the Federal judicial circuit. In 1798, he suffered a bout of malaria and then died of a stroke at the age of 55, while visiting a friend in Edenton, North Carolina. He was buried in the Johnston cemetery on Hayes Plantation near Edenton, but was reinterred in 1906 at Christ Churchyard, Philadelphia.[25]

Tracing over the events of Wilson’s life, we are impressed by the lucid quality of his mind. With this went a restless energy and insatiable ambition, an almost frightening vitality that turned with undiminished energy and enthusiasm to new tasks and new ventures. Yet, when all has been said, the inner man remains, despite our probings, an enigma. — Charles Page Smith[26]

Jurisprudence

In the lectures mentioned above, James Wilson, among the first of American legal philosophers, worked through in more detail some of the thinking suggested in the opinions issuing at that time from the Supreme Court. He felt, in fact, compelled to begin by spending some time in arguing out the justification of the appropriateness of his undertaking a course of lectures. But he assures his students that: "When I deliver my sentiments from this chair, they shall be my honest sentiments: when I deliver them from the bench, they shall be nothing more. In both places I shall make―because I mean to support―the claim to integrity: in neither shall I make―because, in neither, can I support―the claim to infallibility." (First lecture, 1804 Philadelphia ed.)

With this, he raises the most important question of the era: having acted upon revolutionary principles in setting up the new country, "Why should we not teach our children those principles, upon which we ourselves have thought and acted? Ought we to instil into their tender minds a theory, especially if unfounded, which is contradictory to our own practice, built on the most solid foundation? Why should we reduce them to the cruel dilemma of condemning, either those principles which they have been taught to believe, or those persons whom they have been taught to revere?" (First lecture.)

That this is no mere academic question is revealed with a cursory review of any number of early Supreme Court opinions. Perhaps it is best here to quote the opening of Justice Wilson's opinion in Chisholm v. State of Georgia, 2 U.S. 419 (1793), one of the most momentous decisions in American history: "This is a case of uncommon magnitude. One of the parties to it is a State; certainly respectable, claiming to be sovereign. The question to be determined is, whether this State, so respectable, and whose claim soars so high, is amenable to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of the United States? This question, important in itself, will depend on others, more important still; and, may, perhaps, be ultimately resolved into one, no less radical than this 'do the people of the United States form a Nation?'"

In order to arrive at an answer to this question, one that would provide the foundation for the United States of America, Wilson knew that legal thinkers had to resolve in their minds clearly the question of the difference between "the principles of the constitutions and governments and laws of the United States, and the republics, of which they are formed" and the "constitution and government and laws of England." He made it quite clear that he thought the American items to be "materially better." (First lecture.)

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Signers of the Declaration of Independence". ushistory.org. Independence Hall Association. Archived from the original on July 10, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ↑ "James Wilson". University of St. Andrews. Retrieved November 30, 2012. (this source claims that Wilson graduated from St. Andrews, but that claim is contradicted by the previous source)

- ↑ Davies, Ross E. (2010). "The Ancient and Judicial Game: James Wilson, John Marshall Harlan, and the Beginnings of Golf at the Supreme Court". Journal of Supreme Court History. 35: 122-123. SSRN 1573857. .

- ↑ Archives and Records Center. "Penn Biographies: James Wilson (1742-1798)". archives.upenn.edu/. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 8, 2018.

- ↑ "Penn Biographies: James Wilson (1742-1798)".

- ↑ Mark D. Hall, "James Wilson: Presbyterian, Anglican, Thomist, or Deist? Does it Matter?", in Daniel L. Dreisbach, Mark David Hall, Jeffrey Morrison, Jeffry H. Morrison, eds., The Founders on God and Government (2004). p. 181, 184-195.

- ↑ Alexander, Lucien Hugh (1906). James Wilson, Patriot, and the Wilson Doctrine. Philadelphia: The North American Review. p. 1.

- ↑ James Wilson: Founding Father, Charles Page Smith, 1956, p. 72.

- ↑ Page, p. 119.

- ↑ Pennsylvania National Guard (1875). History of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry. Princeton University. p. 17.

- ↑ An Historical Catalogue of The St. Andrew's Society of Philadelphia. Press of Loughead & Co. Philadelphia. 1907. p. 66. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Alexander, John K. (1974). "The Fort Wilson Incident of 1779: A Case Study of the Revolutionary Crowd". The William and Mary Quarterly. 3. 31 (4). Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith, Charles Page. James Wilson Founding Father 1742–1798. Chapel Hill: North Carolina UP, 1956. Print.

- ↑ "Documents from the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention, 1774–1789". loc.gov. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ↑ World Book Encyclopedia, 2003, James Wilson article.

- ↑ "James Wilson: A Forgotten Father," St. John, Gerald J., in The Philadelphia Lawyer, www.philadelphiabar.org.

- ↑ Ketcham, Ralph. James Madison: A Biography, p. 191, American Political Biography Press, Newtown, CT, 1971. ISBN 0-945707-33-9.

- ↑ Read, James H. Power vs. Liberty: Madison, Hamilton, Wilson and Jefferson, p. 93, University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville and London, 2000. ISBN 0-8139-1912-6.

- ↑ Konkle, Burton Alva. "James Wilson and the Constitution," an address to the Law Academy of Philadelphia, November 14, 1906, published by the academy in 1907 Archive.org. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

- ↑ Natelson, Robert G. (2002). "A Republic, Not a Democracy? Initiative, Referendum, and the Constitution's Guarantee Clause". Texas Law Review. 80: 807 [p. 836]. SSRN 1979002. from Elliot, Jonathan, The debate in the several state conventions

- ↑ The American Revolution: A Concise History

- ↑ Bill of Rights

- ↑ James Wilson versus the Bill of Rights

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson and Executive Power

- ↑ St. John, G. J. (2004). "James Wilson: A Forgotten Father". The Philadelphia Lawyer. 66 (4). Retrieved September 10, 2011.

During the dedication of Pennsylvania's new capitol building in Harrisburg, Roosevelt singled out James Wilson for special praise […] One month after the Harrisburg speech, Wilson's remains were removed from Hayes Plantation and reinterred at Old Christ Church

- ↑ Smith (1956), p. 393.

References

- "James Wilson". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- James Wilson at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Works of James Wilson 3 vol (1804) online edition

- Collected Works of James Wilson, 2 vols. Edited by Kermit L. Hall and Mark David Hall. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund Press, 2007.

- Hall, Mark David (1997). The Political and Legal Philosophy of James Wilson, 1742–1798. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-1103-8.

- Read, James H. (2000). Power Versus Liberty: Madison, Hamilton, Wilson, and Jefferson. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0-8139-1911-8.

- Wexler, Natalie (2007). A More Obedient Wife: A Novel of the Early Supreme Court. Washington: Kalorama Press. ISBN 0-615-13516-1.

Further reading

- Brooks, Christopher (2006). Chisholm to Alden: James Wilson's Artificial Person in American Supreme Court History, 1793–1999. Berlin: Logos Verlag. ISBN 3-8325-1342-6.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Ewald, William (June 2008). "James Wilson and the Drafting of the Constitution". University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law. 10: 901–1009.

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the United States Supreme Court. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co., 1874 at Google Books.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L., eds. The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Heyburn, Jack (2017). "Gouverneur Morris and James Wilson at the Constitutional Convention," University of Pennsylvania Journal of Constitutional Law. 20: 169-198.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Pedersen, Nicholas K., "James Wilson: The Lost Founder", Yale Journal of Law & Humanities, 22 (2010), 257–337.

- Smith, Charles Page (1956). James Wilson, Founding Father, 1742–1798. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. p. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

- Witt, John Fabian (2007). "The pyramid and the machine : founding visions in the life of James Wilson". Patriots and Cosmopolitans: Hidden Histories of American Law.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: James Wilson |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: James Wilson |

- Declaration Signers biography of James Wilson

- Penn Law School biography of James Wilson

- Biography by Rev. Charles A. Goodrich, 1856

- Biography and portrait at the University of Pennsylvania

- Portrait at the University of Pennsylvania Law School

- James Wilson at Find a Grave

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- The James Wilson papers, which contain a variety of material on the early federal government and on James Wilson's business and professional activities, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- James Wilson Institute on Natural Rights and the American Founding

- October 6, 1787 "Speech in the Statehouse Yard"

- Wilson, James. "[Letter] 1819 Jan. 23, Washington City, [D.C. to] E. Jackson, Jr". Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New seat | Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1789–1798 |

Succeeded by Bushrod Washington |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||