Francis Hopkinson

| Francis Hopkinson | |

|---|---|

From The literary history of Philadelphia (1906). | |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the District of Pennsylvania | |

|

In office September 26, 1789 – May 9, 1791 | |

| Nominated by | George Washington |

| Succeeded by | William Lewis |

| Delegate from New Jersey to the Second Continental Congress | |

|

In office June 22, 1776 – November 30, 1776 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

September 21, 1737 Philadelphia, Province of Pennsylvania, British America |

| Died |

May 9, 1791 (aged 53) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Resting place | Christ Church Burial Ground, Philadelphia |

| Nationality | American |

| Spouse(s) | Ann Borden |

| Alma mater | The Academy and College of Philadelphia |

| Awards | Magellanic Premium (1790) |

| Signature |

|

Francis Hopkinson (September 21,[1][2] 1737 – May 9, 1791) designed the first official American flag, Continental paper money, and the first U.S. coin. He was an author, a composer, and one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, as a delegate from New Jersey. He served in various roles in the early United States government including as a member of the Second Continental Congress and chairman of the Navy Board. He also later served as a federal district judge in Pennsylvania after the ratification of the Federal Constitution.

Early and Family Life

Francis Hopkinson was born at Philadelphia in 1737, the son of Thomas Hopkinson and Mary Johnson. He became a member of the first class at the College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania) in 1751 and graduated in 1757, receiving his master's degree in 1760, and a doctor in law (honorary) in 1790. He was secretary to a Provincial Council of Pennsylvania Indian commission in 1761 that made a treaty with the Delaware and several Iroquois tribes. In 1763, he was appointed customs collector for Salem, New Jersey. Hopkinson spent from May 1766 to August 1767 in England in hopes of becoming commissioner of customs for North America. Although unsuccessful, he spent time with the future Prime Minister Lord North, Hopkinson's cousin James Johnson (Bishop of Worcester), and the painter Benjamin West.[3]:133

After his return, Hopkinson operated a dry goods business in Philadelphia and married Ann Borden on September 1, 1768. They would have five children.

Legal career

Hopkinson obtained a public appointment as a customs collector for New Castle, Delaware on May 1, 1772. He moved to Bordentown, New Jersey in 1774, became a member of the New Jersey Provincial Council, and was admitted to the New Jersey bar on May 8, 1775. He resigned his crown-appointed positions in 1776 and, on June 22, went on to represent New Jersey in the Second Continental Congress where he signed the Declaration of Independence. He was appointed to Congress' Marine Committee in that year. He departed the Congress on November 30, 1776 to serve on the Navy Board at Philadelphia. The Board reported to the Marine Committee. Hopkinson later became the Navy Board's chairman. As part of the nation's government, he was treasurer of the Continental Loan Office in 1778; appointed judge of the Admiralty Court of Pennsylvania in 1779 and reappointed in 1780 and 1787; and helped ratify the Constitution during the constitutional convention in 1787.[3]:chapter VI [3]:325

On September 24, 1789, President George Washington nominated Hopkinson to the newly created position of judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. He was confirmed by the United States Senate, and received his commission, on September 26, 1789.

Only a few years into his service as a federal judge, Hopkinson died in Philadelphia at the age of 53 from a sudden apoplectic seizure.[3]:449 He was buried in Christ Church Burial Ground in Philadelphia.[4] He was the father of Joseph Hopkinson, who was a member of the United States House of Representatives and also became a federal judge. Hopkinson was the designer of the American flag. He did not get his due in life. At one point, he asked for a quarter cask of wine for his efforts, [3]:241 which he never received.

Cultural contributions

Hopkinson wrote popular airs and political satires (jeux d'esprit) in the form of poems and pamphlets. Some were widely circulated, and powerfully assisted in arousing and fostering the spirit of political independence that issued in the American Revolution. His principal writings are A Pretty Story . . . (1774), a satire about King George, The Prophecy (1776), and The Political Catechism (1777).[5]

Other notable essays are "Typographical Method of conducting a Quarrel", "Essay on White Washing", and "Modern Learning". Many of his writings can be found in Miscellaneous Essays and Occasional Writings, published at Philadelphia in three volumes in 1792 (see Bibliography).

Hopkinson began to play the harpsichord at age seventeen and, during the 1750s, hand-copied arias, songs, and instrumental pieces by many European composers. He is credited as being the first American born composer to commit a composition to paper with his 1759 composition "My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free." By the 1760s he was good enough on the harpsichord to play with professional musicians in concerts. Some of his more notable songs include "The Treaty", "The Battle of the Kegs", and "The New Roof, a song for Federal Mechanics". He also played organ at Philadelphia's Christ Church and composed or edited a number of hymns and psalms including: "A Collection of Psalm Tunes with a few Anthems and Hymns Some of them Entirely New, for the Use of the United Churches of Christ Church and St. Peter's Church in Philadelphia" (1763), "A psalm of thanksgiving, Adapted to the Solemnity of Easter: To be performed on Sunday, the 30th of March, 1766, at Christ Church, Philadelphia" (1766), and "The Psalms of David, with the Ten Commandments, Creed, Lord's Prayer, &c. in Metre" (1767). In the 1780s, Hopkinson modified a glass harmonica to be played with a keyboard and invented the Bellarmonic, an instrument that utilized the tones of metal balls.[6]

At his alma mater, University of Pennsylvania, one of the buildings in the Fisher-Hassenfeld College House is named after him.[7]

Bibliography

Books

- The Miscellaneous Essays and Occasional Writings of Francis Hopkinson, Esq Printed by T. Dobson, 1792. Available via Google Books: Volume I, Volume II, Volume III

- Judgments in the Admiralty of Pennsylvania in four suits Printed at T. Dobson and T. Lang, 1789. Available via Google Books

Essays

- A Pretty Story Written in the Year of Our Lord 1774. Printed by John Dunlap, 1774. Available via Google Books

Musical compositions

Flag controversy

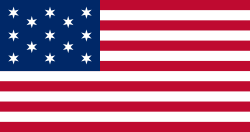

On Saturday, June 14, 1777, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Stars and Stripes as the first official national flag of the newly independent United States (later celebrated as Flag Day). The resolution creating the flag came from the Continental Marine Committee. Hopkinson became a member of the committee in 1776. At the time of the flag's adoption, he was the Chairman of the Navy Board, which was under the Marine Committee. Today, that office and responsibility/power would be residing in the United States Secretary of the Navy.[10]

Hopkinson is recognized as the designer of the Flag of the United States, and the journals of the Continental Congress support this.[11] His first letter in May 25, 1780, requesting compensation from Congress was almost comical. He asked for a quarter cask of wine in payment for designing the U.S. flag, the Great Seal of the United States, and various other contributions. After Congress received a second letter from Hopkinson asking for cash in the amount of £2,700, the Auditor General, James Milligan, commissioned an evaluation of the request for payment. In this second letter, Hopkinson did not mention designing the flag of the United States. Instead, he listed "the great Naval Flag of the United States" (See illustration of flag.) along with the other contributions.[12] The report from the commissioner of the Chamber of Accounts said that the bill was reasonable and ought to be paid. Congress used the usual bureaucratic tactics of asking for an itemized bill for payment in cash. After that, there was further bureaucratic back and forth including a request for an itemized bill and a committee to investigate Hopkinson's charges that his payment was being delayed for arbitrary reasons. Congress eventually refused to pay Hopkinson for the reason that Hopkinson was already paid as a public servant as a member of Congress. Congress also mentioned that Hopkinson was not the only person consulted on the designs that were "incidental" to the Treasury Board. [3]:240–249 This referred to Hopkinson's work on the Great Seal.[13] He served as a consultant to a committee working on the design of the Great Seal.[14][15] Fourteen men worked on the Great Seal, including two other consultants – Pierre Eugene Du Simitiere (first Great Seal committee) and William Barton (third committee).[16] No known committee of the Continental Congress was ever documented with the assignment to design the national flag or naval flag.[17]

There is no known sketch of a Hopkinson flag—either U.S. or naval—in existence today. Hopkinson, however, did incorporate elements of the two flags he designed in his rough sketches of the Great Seal of the United States and his design for the Admiralty Board Seal.[18] The rough sketch of his second Great Seal proposal has 7 white stripes and 6 red stripes.[19] The impression of Hopkinson's Admiralty Board Seal[20] has a chevron with 7 red stripes and 6 white stripes. The Great Seal reflects Hopkinson's design for a governmental flag and the Admiralty Board Seal reflects Hopkinson's design for a naval flag.[21] Both flags were intended to have 13 stripes. Because the original stars used in the Great Seal had six points, Hopkinson's U.S. flag might also have intended the use of 6-pointed stars.[22] This is bolstered by his original sketch[23] that showed asterisks with six points.

The legend of Betsy Ross as the designer of the first flag entered into American consciousness about the time of the 1876 centennial celebrations, owing to the efforts of her grandson, William Canby.[24] This flag with its circle of 13 stars came into popular use as a flag commemorating the nation's birth. Many Americans today still cling to the Betsy Ross legend that she designed the flag, and most are unaware of Hopkinson's legacy. The circle of stars (a circle connotes eternity) first appeared after the war ended and after Hopkinson's original design.[25]

Hopkinson's letter and response

On May 25, 1780, Hopkinson wrote a letter to the Continental Board of Admiralty mentioning several patriotic designs he had completed during the previous three years. One was his Board of Admiralty seal, which contained a shield of seven red and six white stripes on a blue field. Others included the Treasury Board seal, "7 devices for the Continental Currency," and "the Flag of the United States of America."[26]

In the letter, Hopkinson noted that he hadn't asked for any compensation for the designs, but was now looking for a reward: "a Quarter Cask of the public Wine." The board sent that letter on to Congress. Hopkinson submitted another bill on June 24 for his "drawings and devices." The first item on the list was "The Naval Flag of the United States." The price listed was 9 pounds. This flag with its red, outer stripes was designed to show up well on ships at sea.[21] A parallel flag for the national flag was most likely intended by Hopkinson with white, outer stripes[21] as on the Great Seal of the United States and on the Bennington flag, which commemorated 50th anniversary of the founding of the United States (1826).[27] Ironically, the Navy flag was preferred as the national flag.

The Treasury Board turned down the request in an October 27, 1780, report to Congress. The Board cited several reasons for its action, including the fact that Hopkinson "was not the only person consulted on those exhibitions of Fancy [that were incidental to the Board (among them, the U.S. flag, the Navy flag, the Admiralty seal, and the Great Seal with a reverse)[28] ], and therefore cannot claim the sole merit of them and not entitled in this respect to the full sum charged."[29] This is most probably a reference to his work as a consultant to the second committee that worked on the Great Seal of the United States.[30] Therefore, he would not be eligible to be paid for the Great Seal.[31]. Furthermore, the Great Seal project was still a work in progress. The Seal was not finalized until June 20, 1782.[32]

Great Seal of the United States

Francis Hopkinson provided assistance to the second committee that designed the Great Seal of the United States. On today's seal, the 13 stars (constellation) representing the 13 original states have five points. They are arranged in a larger star that has six points. The constellation comprising 13 smaller stars symbolizes the national motto, "E pluribus unum." Originally, the design had individual stars with six points, but this was changed in 1841 when a new die was cast. This seal is now impressed upon the reverse of the United States one-dollar bill. The reverse of the seal, designed by William Barton, contains an unfinished pyramid below a radiant eye. The unfinished pyramid was an image used by Hopkinson when he designed the Continental $50 currency bill.[33][34][35]

See also

- Francis Hopkinson House, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in Burlington County, New Jersey

- George E. Hastings. The Life and Works of Francis Hopkinson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1926.

Notes

- ↑ http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=H000783

- ↑ Francis Hopkinson was born on September 21, 1737, according to the then-used Julian calendar (old style). In 1752, however, Great Britain and all its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar (new style) which moved Hopkinson's birthday 11 days forward to October 2, 1737. See George E. Hastings, The Life and Works of Francis Hopkinson. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1926), p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hastings, George (1926). The Life and Works of Francis Hopkinson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ Francis Hopkinson at Find a Grave

- ↑ Charles Wells Moulton, ed. (1902). The Library of Literary Criticism of English and American Authors: 1785–1824. Buffalo, NY: The Moulton Publishing Company. p. 131.

- ↑ Francis Hopkinson biography at the Library of Congress Performing Arts Digital Library; accessed 30 September 2015.

- ↑ "Hopkinson | Fisher College House". fh.house.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ↑ Pennsylvania Center for the Book on Hopkinson and his writings

- ↑ "Seven Songs for the Harpsichord or Forte Piano". Early American Secular Music and its European Sources, 1589–1839. Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-05-05.

- ↑ Zall, Paul M. (1976). Comical Spirit of Seventy-Six: The Humor of Francis Hopkinson. San Marino, California: Huntington Library. p. 10.

- ↑ Furlong, William Rea; McCandless, Byron (1981). So Proudly We Hail. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 101.

- ↑ Williams, Jr., Earl P. (October 2012). "Did Francis Hopkinson Design Two Flags?" (PDF). NAVA News (216): 7–9. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ↑ Williams, Jr., Earl P. (Spring 1988). "The 'Fancy Work' of Francis Hopkinson: Did He Design the Stars and Stripes?". Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives. 20 (1): 48.

- ↑ transcript

- ↑ Buescher, John. "All Wrapped up in the Flag", Teachinghistory.org, accessed August 21, 2011.

- ↑ Williams, Jr., Earl P. (June 14, 1996). "A Civil Servant Designed Our National Banner: The Unsung Legacy of Francis Hopkinson". The New Constellation (newsletter of the National Flag Foundation). Special Edition #7: 8.

- ↑ Canby, George; Balderston, Lloyd (1909). The Evolution of the American Flag. Philadelphia: Ferris & Leach. p. 48.

- ↑ Williams (2012), pp. 7-9.

- ↑ Patterson, Richard Sharpe; Dougall, Richardson (1978) [1976 i.e. 1978]. The Eagle and the Shield: A History of the Great Seal of the United States. Department and Foreign Service series ; 161 Department of State publication ; 8900. Washington : Office of the Historian, Bureau of Public Affairs, Dept. of State : for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. p. 37. LCCN 78602518. OCLC 4268298.

- ↑ Moeller, Henry W., Ph.D. (January 2002). "Two Early American Ensigns on the Pennsylvania State Arms". NAVA News (173): fn. 41 & 42.

- 1 2 3 Williams (2012), pp. 7–9.

- ↑ Williams (2012), p. 8.

- ↑ Patterson and Dougall, p. 37.

- ↑ Canby and Balderston, pp. 110–11.

- ↑ Cooper, Grace Rogers (1973). Thirteen-Star Flags: Keys to Identification. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 11.

- ↑ Leepson, Marc; DeMille, Nelson. Flag: An American Biography. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-312-32309-7.

- ↑ Joint Committee on Printing, U.S. Congress (2007). Our Flag (Rev. ed.109th Congress, 2nd Session ed.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-0-16-076598-8.

- ↑ Hastings (1926), p. 241-242.

- ↑ Williams (1988), p. 47.

- ↑ Williams (1988), p. 48.

- ↑ Journals of the Continental Congress – Friday, October 27, 1780

- ↑ Patterson and Dougall, p. 83.

- ↑ wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c9/Continental_$50_note_1778

- ↑ Univ. of Notre Dame, Coin and Currency Collections

- ↑ Patterson and Dougall, p. 68

References

- Francis Hopkinson holdings at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania Online Public Access Catalog.

- Mastai, Bolesław; Mastai, Marie-Louise d'Otrange. The Stars and the Stripes; the American flag as art and as history from the birth of the Republic to the present. New York, Knopf, 1973. ISBN 0-394-47217-9.

- Znamierowski, Alfred. The World Encyclopedia of Flags. Hermes House. ISBN 1-84309-042-2.

- "Francis Hopkinson". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Francis Hopkinson at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

External links

- University of Penn. Archives on Hopkinson

- The Hopkinson Family Papers, including correspondence, documents and printed materials, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Pennsylvania Center for the Book on Hopkinson and his writings

- Library of Congress on Hopkinson

- Works by or about Francis Hopkinson in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Francis Hopkinson: Jurist, Wit, and Dilettante Marble, Annie Russell. Heralds of American Literature: A Group of Patriot Writers of the Revolutionary and National Periods. 1907, University of Chicago Press, hosted by Google Book Search

- image of stamp with Hopkinson's flag, stars in a circle, from the University of Georgia

- First American Song by Francis Hopkinson

- Free scores by Francis Hopkinson at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- "AN ACCOUNT OF THE GRAND FEDERAL PROCESSION. PERFORMED AT PHILADELPHIA ON FRIDAY THE 4TH OF JULY 1788" by Francis Hopkinson – Hopkinson's review of a Philadelphia 4 July parade of 1788; celebrating the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

- Works by Francis Hopkinson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

| Legal offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Newly created seat |

Judge of the U.S. District Court for the District of Pennsylvania September 26, 1789 – May 9, 1791 |

Succeeded by William Lewis |