Ottoman illumination

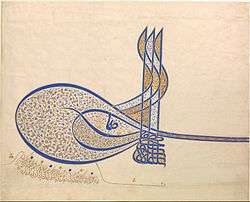

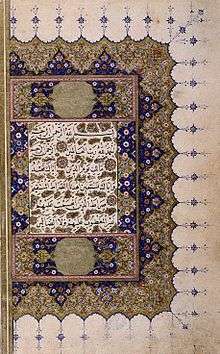

Turkish or Ottoman illumination covers non-figurative painted or drawn decorative art in books or on sheets in muraqqa or albums, as opposed to the figurative images of the Ottoman miniature. In Turkish it is called “tezhip”,[1] meaning “ornamenting with gold”. It was a part of the Ottoman Book Arts together with the Ottoman miniature (taswir),[2] calligraphy (hat),[3] Islamic calligraphy, bookbinding (cilt)[4] and paper marbling (ebru).[5] In the Ottoman Empire, illuminated and illustrated manuscripts were commissioned by the Sultan or the administrators of the court. In Topkapi Palace, these manuscripts were created by the artists working in Nakkashane, the atelier of the miniature and illumination artists. Both religious and non-religious books could be illuminated. Also sheets for albums levha consisted of illuminated calligraphy (hat) of tughra, religious texts, verses from poems or proverbs, and purely decorative drawings.

The illuminations were made either surrounding the text as a frame or within the text in triangle or rectangle forms. There could be a few carpet pages in the book with ornamental compositions covering the whole page without any accompanying text. The motifs consisted of Rumi, Saz Yolu, Penc,[6] Hatai,[7] roses, Leaf Motifs, Palm Leaves, naturalistic flowers, Munhani (gradient colored curve motifs), Dragons, Simurg (Phoenix) Çintamani (Tama motif in Japanese and Chinese book arts).

In the 15th century, Ahmed b. Hacı Mahmut el-Aksarayi was a famous illumination artist who created a unique style in the book Divan-ı Ahmedi in 1437, with multi-colored floral patterns.

In the beginning of the 16th century, Hasan b. Abdullah's works was original for their color harmony. In the second half of the century, Bayram b. Dervish, Nakkaş Kara Mehmed Çelebi (Karamemi) illuminated books about literature and history. Karamemi brought up an innovation to the tradition with his naturalistic floral ornamentations.

17th century illumination art was different from the previous examples due to more use of colors. Hâfiz Osman (1642–1698), invented the calligraphic format of the hilye, or text describing the appearance of Muhammad, which were kept in albums or framed like pictures for hanging on walls. The economic and social crisis effected cultural life and fewer manuscripts were produced in this period compared to the past.

In the 18th century, new ornamental motifs were introduced. The floral designs were three-dimensional and naturalistic and carried the influences of Western art. Ali el-Üsküdari reused the Saz Style which was introduced by painter Shahkulu in the 17th century. Baroque and Rococo styles were used that reflected the influence of cultural Westernization. After the mid-18th century social and economic changes lead to changes in Ottoman cultural life. When the printing press finally became widely used in the 19th century, the demand for illuminated manuscripts were reduced and the artists mostly produced plates for printing.

The 19th century was a period a vast variety of styles. The European baroque and rococo styles were known and adopted by Ottoman illumination artists. Ahmed Efendi, Ali Ragip, Rashid, Ahmed Ataullah were the famous artists of the period. The introduction of printing press, paintings on toil and photography did not have as much negative influences as it did in the case of Ottoman miniature painting. This was because both people and the ruling elites in Ottoman Empire were eager to continue the tradition of illuminating religious texts that came not only as books (like illuminated Qurans) but also as plates to adorn and sanctify their houses and work places. In the 20th century, after the end of Ottoman Empire, the intelligentsia of the newly born Turkish Republic was under the influence of Western art and aesthetics. The Ottoman Book Arts were unfortunately estimated as not as arts but as outdated things of the past. After the Alphabet Reform in 1925 that abolished Ottoman-Arabic characters and adopted Latin alphabet to be used by the citizens of the Republic, Ottoman Calligraphy was doomed to be incomprehensible by the next generation. As Ottoman-Turkish Illumination Art had shared a common fate with Ottoman Calligraphy from the beginning of their history, both arts went through a period of crisis. But there were conservative intellectuals who valued all the Ottoman Book Arts as important artistic traditions that should be kept alive and transmitted to the next generations. Suheyl Unver, Rikkat Kunt, Muhsin Demironat, Ismail Hakki Altunbezer, and Feyzullah Dayigil were some of the intellectuals that played an important role in continuing the tradition of Ottoman/Turkish Illumination Art. With the foundation of Turkish Decorative Arts section within the Academy of Fine Arts, new generations of illumination artists were educated. Today there are many artists in the field of illumination. Some of them are Çiçek Derman, Gülnur Duran, Şahin İnalöz, Cahide Keskiner, Ülker Erke, Melek Anter and Münevver Üçer (all of whom are women).

References

- Turkish Art of Illumination – Ayse Ustun, Turkish Book Arts Symposium pp. 32–47, ISMEK yayinlari 2007

- Turkish Motifs, Cahide Keskiner, Turkish Touring and Automobile Association, 2001

- Turkish Art of Illumiation – Zeren Tanindi

Further reading

- J.M. Rogers; Empire Of The Sultans Ottoman Art

From The Khalili Collection, Art Services International In Association With The Khalili Family Trust 2002.

- Turkish Culture Portal – Illumination