Hurricane Dennis (1999)

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

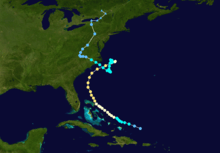

Hurricane Dennis near peak intensity off the coast of Georgia on August 29 | |

| Formed | August 24, 1999 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 9, 1999 |

| (Extratropical after September 7) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 105 mph (165 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 962 mbar (hPa); 28.41 inHg |

| Fatalities | 4 direct |

| Damage | $157 million (1999 USD) |

| Areas affected | Bahamas, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Pennsylvania |

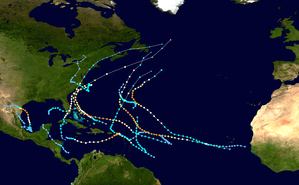

| Part of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Hurricane Dennis caused flooding in North Carolina and the Mid-Atlantic states in early September 1999, which would later be compounded by Hurricane Floyd. The fifth tropical cyclone of the season, Dennis developed from a tropical wave to the north of Puerto Rico on August 24. Originally a tropical depression, the system strengthened into a tropical storm despite unfavorable wind shear. The storm became a hurricane by August 26. After striking the Abaco Islands, conditions improved, allowing for Dennis to strengthen into a Category 2 on the Saffir–Simpson scale by August 28. Around this time, Dennis began to move parallel to the Southeastern United States. Early on August 30, the storm peaked with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h). By the following day, steering currents collapsed and the storm interacted with a cold front, causing Dennis to move erratically offshore North Carolina. Wind shear and cold air associated with the front weakened Dennis to a tropical storm on September 1 and removed some of its tropical characteristics. Eventually, warmer ocean temperatures caused some re-strengthening. By September 4, Dennis turned northwestward and made landfall in Cape Lookout, North Carolina, as a strong tropical storm. The storm slowly weakened inland, before transitioning into an extratropical cyclone over western New York on September 7.

In the Bahamas, Dennis produced moderate winds, rain, and storm surge on San Salvador, Crooked Island, Eleuthera, and Abaco Islands, resulting in damage to roofs and coastal properties. Dennis brought 6–8 feet (1.8–2.4 m) waves to the east coast of Florida, causing minor erosion and four drowning deaths. The waves left severe erosion and coastal flooding along the Outer Banks of North Carolina. An 8 ft (2.4 m) deep channel created along Highway 12 isolated three towns on Hatteras Island. In Carteret, Craven, and Dare counties, the storm damaged at least 2,025 homes and businesses to some degree. Heavy rainfall fell in eastern North Carolina. Although the precipitation was generally beneficial due to drought conditions, it also damaged crops. Two indirect deaths occurred in Richlands during a weather-related car accident. Similar inland flooding occurred in northern and eastern Virginia. A tornado in Hampton severely damaged five apartment complexes, three of which were condemned completely, as well an assisted living facility; about 460 people were forced to evacuate from the buildings, and as many as 800 vehicles may have been damaged. Overall, damage in North Carolina and Virginia totaled about $157 million (1999 USD). Generally minor flooding occurred in the Mid-Atlantic and New England.

Meteorological history

On August 17, a tropical wave emerged off the western coast of Africa. Tracking steadily westward, the wave remained devoid of significant convection until August 21, when associated shower and thunderstorm activity increased a few hundred miles northeast of the Leeward Islands. Over the course of the next two days, the development of a low-level circulation was noted, though a reconnaissance aircraft failed to locate the presence of a surface low on August 23. Subsequent surface observations indicated the formation of a circulation at the surface, and the wave acquired enough organization to be designated as a tropical depression at 0000 UTC on August 24, while centered 220 mi (355 km) east of Turks Island. Data from a secondary reconnaissance aircraft and ship reports indicated intensification, and the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Dennis at 1200 UTC that same day accordingly. Located at the tail-end of a stationary trough and in an environment of unfavorable wind shear, the system was ill-defined and asymmetric. Despite the unfavorable environment, data from the Hurricane Hunters indicated that Dennis had intensified into a Category 1 hurricane by 0600 UTC on August 26.[1][2]

Tracking west-northwestward in advance of a trough over the eastern United States, the system did not resemble a typical hurricane on satellite imagery, with a low-level center outside of the deepest convection.[3] The system turned towards the northwest and simultaneously slowed in motion by August 27 as a second mid-latitude trough passed to its north. Though wind shear remained unfavorable initially, it began to lessen on August 28 as an anticyclone developed aloft. At 1200 UTC, Dennis was upgraded to a Category 2 hurricane and reached peak winds of 105 mph (165 km/h), though its lowest barometric pressure was recorded until 0600 UTC on August 30. Despite this intensity, the hurricane's eye was large, up to 30-40 mi (50-65 km) wide, and several fixes from the Hurricane Hunters did not indicate the presence of one at all. The system also became unusually large, with its radius of maximum sustained winds extending up to 70-85 mi (110-130 km) wide. Following peak intensity, Dennis accelerated towards the northeastward in response to the secondary trough, barely missing the Outer Banks. By August 31, steering currents collapsed and the hurricane began to aimlessly drift east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.[2]

Though the upper-level trough advanced eastward away from the hurricane, a trailing cold front became intertwined with Dennis, forcing dry air into the circulation in addition to creating a hostile upper-level environment. On September 1, the system weakened below hurricane intensity, with the National Hurricane Center (NHC) noting that the storm could be as much an extratropical as a subtropical or tropical cyclone. Thereafter, a building ridge over the eastern United States forced the storm southward across slightly warmer ocean temperatures.[2] As a result, banding features became better defined despite low convective tops as viewed on radar and in satellite imagery.[4] On September 3, the high drifted eastward into the Atlantic, forcing Dennis to turn northwestward. A formative eyewall was observed on September 4,[5] and Dennis reached a secondary peak intensity with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) by 1800 UTC. Three hours later, the system moved ashore the Cape Lookout National Seashore in eastern North Carolina at this intensity. Continuing inland, Dennis weakened to a tropical depression over central North Carolina at 1200 UTC on September 5. The cyclone drifted erratically even overland, turning northeast and eventually north before dissipating over New York at 1800 UTC on September 7. Two days later, the low was absorbed into a larger cyclone.[2]

Preparations

The erratic motion of Hurricane Dennis resulted in several tropical storm watches and warnings, as well as hurricane watches and warning to be issued. Alerts from this hurricane were issued starting on August 24, at which time a tropical storm warning was put it place for the southeast Bahamas and Turks and Caicos Islands, simultaneously, a tropical storm watch was also issued for the central Bahamas. Less than 24 hours, the tropical storm watch was upgraded to a tropical storm warning, while there was also an additional hurricane watch. All watches and warnings within the Bahamas were discontinued by late August 28.[2]

Watches and warnings in the United States started on August 27 with a hurricane watch being issued from Sebastian Inlet, Florida to Fernandina Beach, Florida. A tropical storm warning was also issued for much of the same area several hours later. As Hurricane Dennis began turning northward, the threat of it strike Florida lessened, which resulted in discontinuations of the watches and warnings.[2] As Dennis moved closer to the North Carolina shore, evacuations were recommended to residents and visitors of the Outer Banks area of the state.[6]

Impact

Dennis left $157 million (1999 USD) in damage and four deaths in Florida, North Carolina, Virginia and the northeastern United States.[7] The heavy rain from Dennis staged a catastrophic flood disaster wrought by Hurricane Floyd about two weeks later.

Bahamas

Dennis brought tropical storm and hurricane-force winds to the Bahamas. In Grand Bahama, a weather station reported winds of 40 mph (64 km/h) while other areas reported winds between 70 and 75 mph (113 and 121 km/h). A 976 mbar (28.8 inHg) reading and storm tides 1–3 ft (0.30–0.91 m) above normal occurred as the center of the storm moved across Abaco Island on August 28. The only official rainfall total from the Bahamas was 4.4 in (110 mm) at Eleuthera and Abaco.[2] Dennis caused moderate damage across the Bahamas. On Abaco Island, the rain caused heavy flooding and storm surge washed out roads. Dennis also caused considerable damage to trees and boats. Widespread power outages were also reported.[8] However, there were no reports of deaths or injuries and damage totals from the Bahamas are unavailable.[2]

Southeastern United States

When Dennis was offshore the storm brought winds up to 35 mph (56 km/h) with gusts reaching to 40 mph (64 km/h) to Jacksonville, Florida. In St. Augustine, a weather station reported a 35 mph (56 km/h) gust. Rainfall from Dennis was minimal, amounting to only 0.11 inches (2.8 mm) at Jacksonville International Airport. Dennis also brought storm tides between 6–8 feet in some areas and there was only minor beach erosion. The strong rip currents brought by Dennis caused one fatality.[9]

The state of Georgia reported 35 mph (56 km/h) wind gusts and only a trace of rain.[10]

In South Carolina, numerous weather stations reported winds between 40-55 mph and gusts reaching hurricane force. Rainfall up to 1.2 inches (30 mm) fell in some areas while buoys offshore reported tides 2 feet (0.61 m) above normal. Minor to moderate beach erosion was reported from Charleston to Colleton County. Damage in South Carolina was limited to downed trees and scattered power outages.[10]

North Carolina

Dennis brought tropical storm force winds with gusts up to hurricane force to the North Carolina coast. In Oregon Inlet, there were 60 mph (97 km/h) winds, while Cape Hatteras and Wrightsville Beach reported gusts between 90-100 mph. A weather station reported 90 mph (140 km/h) wind gusts and a barometric pressure reading of 977 mbar. When Dennis made landfall on September 4, it brought tropical storm force winds to much of eastern North Carolina. 45 mph (72 km/h) winds were reported in Cherry Point, North Carolina. Storm tides 3–5 feet above normal were reported along the North Carolina coast. Because Dennis was a slow moving storm, it produced heavy rains across eastern North Carolina. The highest rainfall total was 19.13 inches (486 mm) in Ocracoke, while rainfall between 3-10 inches was reported elsewhere. It left three towns in Hatteras Island isolated from the rest of the state as it created an eight foot deep channel in North Carolina Highway 12.[6] It cut off the route between Avon, North Carolina and Buxton, North Carolina and left four feet of sand lying upon portions of Highway 12.[6]

The rain was beneficial as it broke a prolonged dry spell, but it also staged the catastrophic flood disaster caused by Hurricane Floyd a month later. The heavy rains caused significant flooding that left $60 million (1999 USD) in structural damage and $37 million (1999 USD) in agricultural damage — totaling $97 million (1999 USD).[2] In addition, Dennis caused two indirect deaths when two cars collided during the storm. The heavy rains knocked down power lines near Wilmington, North Carolina, leaving 56,000 residents without electricity.[8]

Virginia and Mid-Atlantic

The remnants of Dennis tracked across Maryland between September 4 and September 6, producing heavy rainfall in central portions of the state and tidal flooding along the western shoreline of the Chesapeake Bay. Rainfall totals include 5.59 inches (142 mm) at Clarksburg, 4.50 inches (114 mm) at Glenmont, and 4.41 inches (112 mm) at Gaithersburg. Winds in the state gusted to 35 miles per hour (56 km/h), causing downed tree limbs and scattered power outages. Associated lightning in Allegany County struck two main power poles. The incident forced the closer of Interstate 68 and left 4,700 customers without power. Tides generally ran 2 to 3 feet (0.61 to 0.91 m) above normal along the coast; coastal flooding was reported at several locations. Two days of heavy rain swelled Jones Falls Creek, which swept away a 13-year-old boy. After an hour, he was rescued from a pile of debris and treated for hypothermia. Street flooding of up to 2 feet (0.61 m) in depth was reported. In Baltimore, persistent winds pushed water over a seawall at Inner Harbor.[11]

Periods of heavy rain, street flooding, wind gusts of up to 35 miles per hour (56 km/h), and tidal flooding along the Potomac River were also reported in Washington, D.C. The Washington Reagan National Airport recorded 2.31 inches (59 mm) of rain. The winds resulted in isolated power outages throughout the District. To protect the Washington Harbor, officials erected a flood wall along the Potomac River. The storm also dropped light rainfall in parts of Delaware.[11]

Rainfall in Pennsylvania reached 7.29 inches (185 mm) at Lewisburg.[12] Elsewhere, in Lycoming County, 4 to 8 inches (100 to 200 mm) of precipitation was reported. The heavy rainfall triggered flash flooding that was compared to that of Hurricane Agnes in 1972. In Montgomery, 30 houses were damaged and 80 residents were evacuated. Also struck severely by the flooding was Union County. Several hundred homes and businesses were affected, and throughout the county, numerous vehicles were damaged. Elsewhere, trailers were swept away by the flood waters. Campers along the banks of various creeks were forced to higher ground. An entire neighborhood in Swatara Township evacuated when flood waters reached depths of 8 feet (2.4 m). Across the region, basements and roads were flooded. In addition, mudslides closed two highways north of Liverpool.[11]

A narrow band of rainfall produce precipitation rates of over 2 inches (51 mm) per hour in some areas across southeastern New York, which resulted in significant street flooding. The heaviest precipitation fell on the higher terrain of southeast Orange County and northwest Rockland County. On some roads, flood waters accumulated to 3 feet (0.91 m) deep; this led to stalled vehicles. Several basements were flooded in the region.[11] In New York City, a period of hot weather, followed by heavy rainfall from the remnants of Dennis, contributed to the formation of a swarm of disease-carrying mosquitoes.[13] A strong high pressure system developed over eastern Canada and New England. Combined with swells from Hurricane Dennis, beach erosion, rouge surf, and minor tidal flooding battered the coast of New Jersey. Tides ranged as high as 7 feet (2.1 m) along the coast, and street flooding was reported onshore. As a result of the rouge surf, swimming restrictions were set as far north as Long Island.[6] The beach at Cape Map Point lost approximately 1 foot (0.30 m) of sand to the erosion.[11] Moderate rainfall extended into New England, where in excess of 3 inches (76 mm) of precipitation was recorded.[14]

Aftermath

Dennis caused four deaths in Florida, all due to high surf. There were no reported deaths due to winds, rains, storm tides or tornadoes.[7] In North Carolina and Virginia, insurance claims for damaged property totaled $60 million. Agricultural losses in the two states were about $37 million. The total estimated damage cost for Dennis was approximately $157 million.[7]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Dennis (1999). |

References

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (August 26, 1999). Hurricane Dennis Discussion Number 10. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jack L. Beven (January 11, 2000). Preliminary Report: Hurricane Dennis. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 4, 2013. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Lixion A. Avila (August 26, 1999). Hurricane Dennis Discussion Number 11. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (September 3, 1999). Tropical Storm Dennis Discussion Number 43. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- ↑ Jack L. Beven (September 4, 1999). Tropical Storm Dennis Discussion Number 43. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Estes Thompson (September 1, 1999). "Dennis Forcing Residents To Flee". The Columbian. Associated Press. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Beven, Jack (11 January 2000). Tropical Cyclone Dennis Preliminary Report (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- 1 2 1999 Damage Reports (Report). Hurricane City.com. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ↑ CNN Report from Florida

- 1 2 CNN report from Georgia and South Carolina

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena" (PDF). Storm Data. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. 9 (41). September 1999. ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2014. Retrieved July 6, 2014.

- ↑ Roth, David M; Weather Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ Staff Writer (September 20, 1999). "Barkers at pleasure beach side shows". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

- ↑ Roth, David M; Hydrometeorological Prediction Center (2012). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall for the New England United States". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Point Maxima. United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Retrieved June 23, 2012.