Holland House

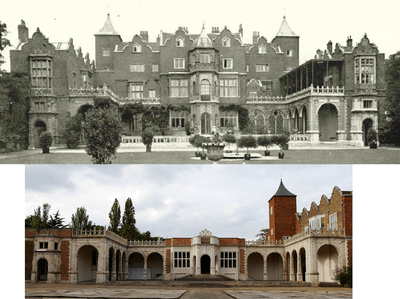

Holland House,[2] originally known as Cope Castle, was an early Jacobean country house built in 1605 by the diplomat Sir Walter Cope as the manor house[3] of the manor of Kensington, and situated west of the village of Kensington, about 3 1/2 miles west of the City of Westminster and 5 miles south-west of the City of London, situated within a deer-park now known as Holland Park and now fully surrounded by the modern buildings of Central London. The house later passed by marriage to Henry Rich, 1st Baron Kensington, 1st Earl of Holland, later to the Fox family, created Baron Holland in 1763, under whose ownership it became a noted gathering-place for Whigs in the 19th century. The house was largely destroyed by German firebombing during the Blitz in 1940 and today only the east wing remains intact, with ruins of the ground floor of the south facade remaining, as well as various outbuildings, including a large orangery, and formal gardens. In 1949 the ruin was designated a grade I listed building.[4] It is now owned by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Descent

Cope

Sir Walter Cope (c.1553-1614)

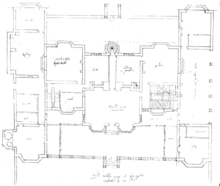

The house was commissioned in 1604 from the architect John Thorpe[lower-alpha 1] by Sir Walter Cope (c.1553-1614), Master of the Court of Wards, Chamberlain of the Exchequer, public Registrar-General of Commerce and a Member of Parliament for Westminster. The building was of a common shape for large houses of the time,[6] containing a centre block and two porches.[7] Many times at Holland House Cope entertained King James I and his consort Queen Anne of Denmark; in 1608 John Chamberlain, the noted author of letters, complained that he "had the honour to see all, but touch nothing, not so much as a cherry, which are charily preserved for the queen's coming."[8] In November 1612 King James I, following the death of his eldest son Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, spent the night at Cope Castle, being joined the following day by his next son Prince Charles and daughter Princess Elizabeth, and her fiancé Frederick V, Elector Palatine.[9] Cope died in 1614 without a son and thus the house was inherited by his daughter Isabel Cope, who in 1616, two years after her father's death, married Henry Rich (1590-1649), whose property it thus became.

Rich

Henry Rich, 1st Earl of Holland (1590-1649)

In 1616 Henry Rich, 1st Baron Kensington, 1st Earl of Holland (1590-1649) inherited Holland House, having married the heiress Isabel Cope, daughter of Walter Cope. He was the second son of Robert Rich, 1st Earl of Warwick (1559-1619). Shortly after the marriage he was granted by the king the titles of Baron Kensington (1622) and Earl of Holland (1624). Upon gaining the latter he re-named the building "Holland House". The building received a large expansion between 1625 and 1635, including two wings and arcades.[7][10] In 1629 he commissioned the surviving stone gate piers from the architect Inigo Jones. He was beheaded in 1649, at the start of the Commonwealth, for his Royalist activities during the Civil War. The house was then used as an army headquarters, being regularly visited by Oliver Cromwell. Lord Holland's headless ghost was reported to haunt the house, carrying its head under its arm.[11] Holland House passed to his descendants.

Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Holland, 5th Earl of Warwick (c. 1620–1675)

Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Holland, 5th Earl of Warwick (c. 1620–1675), eldest son, who in 1673 succeeded his first cousin as fifth Earl of Warwick. The latter earldom is commemorated by today's Warwick Road and Warwick Gardens, to the south west of Holland House.[12]

Edward Rich, 3rd Earl of Holland, 6th Earl of Warwick (1673–1701)

Edward Rich, 3rd Earl of Holland, 6th Earl of Warwick (1673–1701), son, who early 1697 married Charlotte Myddelton (1680–1731), only child of Sir Thomas Myddelton, 2nd Baronet of Chirk Castle, Denbighshire.

King William III (1689-1702) considered moving to Holland House for health reasons. He had been a lifelong sufferer from asthma, which condition was exacerbated by the damp air at the riverside location of the Palace of Whitehall.[13] Attempting to improve his health, he decided to move his court. After a short time spent at Hampton Court, he decided to find another home that was near enough to the capital to easily carry out royal business, but far enough away from the air of London not to threaten his health. He considered Holland House for the purpose, and stayed there for some weeks. Several of his letters are dated from Holland House.[14] Eventually he purchased nearby Kensington House, the residence of Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham, which became Kensington Palace.

Joseph Addison

The wife of the 6th Earl of Warwick survived him and in 1716 re-married to the celebrated writer Joseph Addison (1672-1719). It is stated in certain sources that Addison was her son's tutor which assertion according to Faulkner (1820) is "without the least shadow of proof and which appears to be positively contradicted by facts".[15] Addison lived at Holland House after his marriage, which was not a happy one, and died there three years later in 1719.[16] He is said to have been "in the habit of beguiling his leisure hours" drinking at the White Horse Inn, at the entrance of the back lane to Holland House.[17] On his death bed he called for his young step-son, the future 7th Earl of Warwick, and told him: "See in what peace a Christian can die".[18]Thus Charlotte "by linking with the associations of Kensington the memory of that illustrious man, has invested with a classic halo the groves and shades of Holland House."[19] Many streets developed a century later on the Ilchester Estate west of Holland Park were named after Addison.

Edward Henry Rich, 4th Earl of Holland, 7th Earl of Warwick (1697–1721)

Edward Henry Rich, 4th Earl of Holland, 7th Earl of Warwick (1697–1721), son, to whom there is a monument[20] in St Mary Abbot's Church, Kensington, the parish church of Holland House (rebuilt in the 19th century). He died aged 23, childless and unmarried. His titles, but not his estates, were inherited by his cousin Edward Henry Rich, 10th Baron Rich, 8th Earl of Warwick and 5th Earl of Holland (1695–1759), who also died without male progeny when the titles became extinct. Holland House however was inherited by Lady Elizabeth Rich, the 7th Earl of Warwick's aunt, the sister of the 6th/3rd Earl and wife of Francis Edwardes, of Pembrokeshire.[21]

Edwardes

Francis Edwardes (d.1725)

Francis Edwardes (d.1725), of Johnston,[23] near Haverfordwest in Pembrokeshire, Wales, a Member of Parliament for Haverfordwest (1722), married Lady Elizabeth Rich (d.1725), heir to Holland House, the sister of Edward Rich, 3rd Earl of Holland, 6th Earl of Warwick (1673–1701), and heir-at-law of her nephew Edward Rich, 7th Earl of Warwick, 4th Earl of Holland (1698–1721), who died intestate in 1721.[24] According to Edward Harley, 2nd Earl of Oxford (1689–1741): "Lady Elizabeth Rich had run out her fortune and retired to Wales, and there married Francis Edwardes, who was a younger son of a gentleman; he was a purser of a ship; got £60 per ann(um)".[25] The Edwardes family owned extensive lands in Pembrokeshire, Carmarthenshire and Cardiganshire in Wales. One year after his wife's inheritance he was elected a Member of Parliament. On his death in 1725 Holland House passed to his son Edward Henry Edwardes (d.1738)

Edward Henry Edwardes (d.1738)

Edward Henry Edwardes (d.1738), son, who bequeathed Holland House to his brother William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington (c.1711-1801),[26] although subject to an entail.[27]

William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington (c.1711-1801)

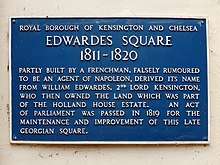

William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington (c.1711-1801), brother,[28] a Member of Parliament for Haverfordwest who was elevated to the Peerage of Ireland as Baron Kensington in 1776. The Edwardes family, after whom is named Edwardes Square which they developed in 1811 to the immediate south-west of Holland House beyond Kensington High Street, appears never to have lived in Holland House,[29] which since 1746 William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington had let as his residence to his parliamentary colleague[30] Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland (1705-1774), a leading Whig politician who served as Secretary at War, Southern Secretary and Paymaster of the Forces.

Fox

Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland (1705-1774)

In 1749 Henry Fox (1705-1 July 1774), later created Baron Holland, obtained a lease from William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington of the house and sixty-four acres of land for "99 years or three lives".[31] His elder brother was Stephen Fox-Strangways, 1st Earl of Ilchester (1704–1776), whose descendants eventually inherited Holland House in 1874. By 1767, Fox was leasing all of Edwardes' estate north of the Hammersmith road (the modern Kensington High Street) (the Edwards family retained the estate to the south), and in 1768 completed the purchase of the 200 acres[31] of land for £17,000, with a further £2,500 paid in compensation to Rowland Edwardes and John Owen Edwardes, the beneficiaries of the entail established by Edward Henry Edwardes (d.1738).[lower-alpha 2] As was usual, a private Act of Parliament was obtained to break the entail and confirm the conveyance.[32] In 1770 Fox's Holland House estate comprised 237 acres.[33] The sale included the lordship of the manor of Abbots Kensington, and situated on the estate (apart from Holland House itself) was Little Holland House, the dower house, with two or three more minor houses and a tavern.[34] Fox died at Holland House in 1774 and thereafter it was inherited by his descendants.

Charles James Fox (1749-1806)

The eldest son and heir of the 1st Baron was Stephen Fox, 2nd Baron Holland (1745-26 December 1774), who survived him just 6 months, but more celebrated was his second son Charles James Fox (1749-1806), the Whig statesman and arch-rival of William Pitt the Younger, during whose life Holland House became the social centre of the Whig party,[35] out of power for the last 23 years of his life. His nephew, the 3rd Baron, acted as host for Charles James Fox's Whig dinners, and after his death in 1806 Holland House became his shrine, with his statue placed in the hall. "Holland's dinners kept the Whig party alive during long years of opposition, and by opening his doors to new talent and new ideas, he ensured that the party didn't stand still".[36] The Whigs were out of power from 1783 to 1806 and again from 1807 to 1830 (in power for just 1 out of 47 years), after which prolonged hiatus they passed the Great Reform Act of 1832, which revolutionised the system of voting and parliamentary representation.

Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840)

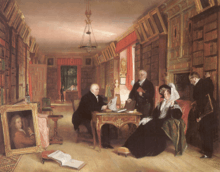

During the tenure of Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840) (son of the 2nd Baron) and his wife Elizabeth Vassall (1771-1845), only daughter of Richard Vassall of Jamaica, the house became a glittering social, literary and political centre with many celebrated visitors such as Lord Byron, Thomas Macaulay ("who painted a brilliant picture of the society at Holland House"[37]), the poets Thomas Campbell and Samuel Rogers, Richard "Conversation" Sharp, Benjamin Disraeli, Charles Dickens and Sir Walter Scott. In his Memoirs, the diarist Charles Greville called Lady Holland "a social light which illuminated and adorned England, and even Europe, for half a century". Both were admirers of Napoleon Bonaparte and sent him books during his exile on St Helena. The political and historical writer John Allen was so much associated with the house that he was known as Holland House Allen and a room in the house was named after him.[38] Lady Caroline Lamb, who had first met her lover Lord Byron at Holland House, satirised it in her 1816 novel Glenarvon.[39] The "Holland House set" required for membership "a certain amount of talent and aristocratic breeding, and it became home to the key British and foreign intellectuals of the day, who gathered to dine and discuss history, literature and politics. With no strict religious agenda, the most common bond and topic of conversation at the evenings was often Whig politics and developments in government. The set was celebrated, long after its end, as Britain's closest thing to a continental salon, representing a strong political and social force".[40]

Development of estate

Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland (1773-1840) was the first to start development of the estate, and his letter dated 13 May 1823 refers to the marking out of the future Addison Road as an "important profitable but melancholy occupation" and in 1824 he mentioned the "tremendous and I hope. . . profitable works" then being undertaken on his estate. The development was used as collateral to raise loans to finance the family's expensive lifestyle at Holland House and Lady Holland wrote to her son: "remote posterity may benefit because for some generations it must be tightly mortgaged ... none now alive will be much bettered by the undertaking".[41]

Henry Edward Fox, 4th Baron Holland (1802-1859)

Henry Edward Fox, 4th Baron Holland (1802-1859), son and heir, who at some time before 1894[42] moved the entrance from the south front to the east side. On the south front he created a terrace enclosed by a low balustrade, having removed the celebrated Inigo Jones gate-piers[43] to the east side, spaced further apart, as an entrance to the pleasure grounds.[44] In place of the original entrance hall on the south side he created a "breakfast room".[45] He married Lady Mary Augusta Coventry (1812-1889), a daughter of George Coventry, 8th Earl of Coventry, by whom he had three children, who all died as infants. However in 1851 he and his wife adopted a three-month old French girl of unknown paternity, who became known as Mary Fox (1850-1878), later as Princess of Liechtenstein, having married Prince Louis of Liechtenstein. She was brought up at Holland House but spent much of her married life at Vienna. She died aged 28. In 1874 she published a history of Holland House, in two volumes. He died at Naples in 1859, without surviving progeny when the title "Baron Holland" became extinct. His widow continued to live at Holland House until her death in 1889, gradually selling off outlying parts of the park for development.

Fox-Strangways

Henry Fox-Strangways, 5th Earl of Ilchester (1847-1905)

Henry Fox-Strangways, 5th Earl of Ilchester (1847-1905), of Melbury House in Melbury Sampford in Dorset, a distant cousin (descended from the elder brother of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland (1705-1774)), inherited Holland House in 1874. He owned large estates in Dorset and lived in Holland House following the death of Lady Holland in 1889.[46] When he entered into possession of the Holland House estate the total income from rents was £3,227. From this he had to pay a large annuity to Lady Holland.[47] It appears that the Earl was "in part motivated by the desire to preserve Holland House and its grounds from speculators" but had taken on financial burdens together with his inheritance which needed to be mitigated. He immediately made plans to develop part of the land to the west of Holland House, which became Melbury Road, named after his Dorset seat. Lady Holland, still living in Holland House, had objected and wrote that "all the building is a very bitter and sad pill to me".[48] Most of the already developed land had been let on long leases not expiring until 1904, after which he had scope to effect further development.

Giles Fox-Strangways, 6th Earl of Ilchester (1874-1959)

Giles Fox-Strangways, 6th Earl of Ilchester (1874-1959) inherited Holland House in 1905. Much of the land to the west of Holland House was developed for housing, including Ilchester Place, completed in 1928,[49] Abbotsbury Road (now forming the western boundary of Holland Park), named after Abbotsbury Abbey in Dorset, acquired in 1543 by Sir Giles Strangways[50] (died 1546) at the Dissolution of the Monasteries and several roads named Addison, after the famous resident of Holland House. The 6th Earl wrote several works on Holland House, including: Catalogue of pictures belonging to the Earl of Ilchester at Holland House,, 1904; The House of the Hollands 1605-1820, 1937; Chronicles of Holland House, 1820-1900, 1937. In 1939 King George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended the debutante ball of Rosalind Cubitt, daughter of Roland Cubitt, 3rd Baron Ashcombe and the former Sonia Keppel, the last great ball held at the house.[51][52] The following year, on 7 September, the German bombing raids on London, the Blitz, began. During the night of 27 September, Holland House was hit by twenty-two incendiary bombs during a ten-hour raid. The house was largely destroyed, with only the east wing, and, miraculously, almost all of the library remaining undamaged. Surviving volumes included the sixteenth-century Boxer Codex. Holland House was designated a grade I listed building in 1949,[53] under the auspices of the Town and Country Planning Act 1947; the Act sought to identify and preserve buildings of special historic importance, prompted by the damage caused by wartime bombing.[54] The building remained a burned-out ruin until 1952, when its owner, the 6th Earl sold the house and fifty-two acres to London County Council for £250,000.[55] He died in 1959. The family retained the developed land adjoining the west side of Holland Park, and together with the family's Dorset properties trade as "Ilchester Estates", managed by the Agent W.A. Ellis.[56]

Edward Fox-Strangways, 7th Earl of Ilchester (1905–1964)

Edward Henry Charles James Fox-Strangways, 7th Earl of Ilchester (1905–1964), son, owner of the Holland House estate, except the park and house sold to LCC. He married Helen Elizabeth Ward, a daughter of Captain Hon. Cyril Augustus Ward. Both his sons predeceased him, so the titles, but not his estates, were inherited by his 4th cousin Walter Angelo Fox-Strangways, 8th Earl of Ilchester (1887–1970). His estates he bequeathed to his only daughter Lady Theresa Jane Fox-Strangways (1932-1989), who married Simon Monckton-Arundell, 9th Viscount Galway.

Monckton-Arundell

In 1999 the owner of Ilchester Estates was Mrs Charlotte Townshend (born 1955), of Melbury House, said to be the richest woman in Britain after the Queen.[57] She was born Hon. Charlotte Anne Monckton-Arundell, the only surviving daughter and heiress of Simon Monckton-Arundell, 9th Viscount Galway (1929–1971), by his wife Lady Teresa Fox-Strangways (died 1989), only surviving child and heiress of Edward Henry Charles James Fox-Strangways, 7th Earl of Ilchester (1905–1964). In 1995 Charlotte married secondly to James Townshend, a land agent. She was a Deputy Lieutenant for Dorset in 1999 and High Sheriff of Dorset in 2005[58] and was joint master of the Cattistock Foxhounds. Besides the Ilchester estates in Kensington and 15,000 acres in Dorset (located in Abbotsbury, Evershot, Melbury Osmond, Stinsford and Charminster,[59] and including 17 mile long Chesil Beach), she also inherited the 3,000 acre[60] Serlby Hall estate in Nottinghamshire from her father, which she sold in 1981, and according to the 2012 Rich List was said to be worth £342 million. Her ownership of the manor of Abbotsbury together with its ancient rights accorded to the Abbey, makes her the only person in Britain allowed to own swans apart from the monarch, and 600 of these are kept by her at Abbotsbury Swannery.

Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

In 1965 the remains of the building passed from the London County Council to its successor, the Greater London Council, and upon the dissolution of the GLC in 1986 to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, the present owner. Today, the remains of Holland House form a backdrop for the open air Holland Park Theatre, home of Opera Holland Park. The YHA (England and Wales) "London Holland Park" youth hostel was located in the house but has now closed. The Orangery is now an exhibition and function space, with the adjoining former Summer Ballroom now a restaurant, The Belvedere. The former ice house is now a gallery space. The grounds provide sporting facilities, including a cricket pitch, football pitch, and six tennis courts. In 1962, the Holland estate sold a piece of land immediately to the south of what is now the sports field for the construction of the Commonwealth Institute.

Estate

At the time of its creation in 1605, the house possessed a 500 acre (200 ha; 0.78 sq mi) estate which stretched from today's Holland Park Avenue in the north almost to the Fulham Road in the south.[31] It contained exotic trees imported by John Tradescant the Younger.[38] By 1768, when it was purchased by Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland from William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington, it had shrunk to two hundred acres.[31] At the beginning of the 20th century, Holland House had the largest private grounds of any house in London, including Buckingham Palace.[7] The Royal Horticultural Society regularly held flower shows there.

Dahlias

In 1804 the garden of Holland House saw one of the earliest successful growths of the dahlia in England. Whilst in Madrid, Lady Holland was given either dahlia seeds or roots by botanist Antonio José Cavanilles.[61] She sent them back to England, to Lord Holland's librarian Mr Buonaiuti at Holland House, who successfully raised the plants.[62][63]

Inigo Jones gate-piers

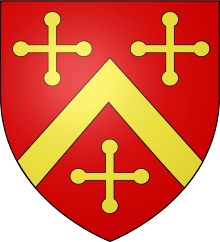

In 1629 Henry Rich, 1st Baron Kensington, 1st Earl of Holland (1590-1649) commissioned Inigo Jones[64] at a cost of £100 to design and the master mason Nicholas Stone to sculpt a pair of Portland stone piers, in order to support large wooden gates for the house.[lower-alpha 3] The piers, still extant, take the form of narrow Doric temples with a central arched niche with heraldic escutcheon above, each topped by a griffin supporting an escutcheon. Either or both sets of escutcheons display the arms of Rich[67] quartering Bouldry and impaling Cope,[68] symbolising the union of the two families. The piers have been moved to new positions on several occasions. While their exact original position is not known, in the 18th century they were moved from "the centre of the court"[69] and repositioned very widely apart on either side of the south front of the house, as shown in an engraving dated 1823.[70] In 1848 as part of a major restructuring of the house by the 4th Baron Holland, the piers were moved to the eastern side of the house, which became the main entrance, and served as a gateway northwards into the pleasure gardens. Following the house's destruction in the Second World War, and the conversion in 1959 of the remains of the east wing into a youth hostel, the piers were returned to the south side,[67] close to the house, to form the entrance to the courtyard.

Little Holland House

The house's dower house, known as Little Holland House, became the centre of a Victorian artistic salon presided over by the Prinseps and the painter George Frederic Watts.

Interior

Gilt Chamber

Harper's New Monthly Magazine described Holland House as having had a "Gilt Chamber", where "the figures over the fireplace were painted in flesh colour wherever bare; the rest was in shaded gold. The lower marbles of the fireplace were black, and the upper ones were Sienna; the capitals and bases of the columns and pilasters were gilt, and the groundwork from which all the glittering decoration rose was white."[71] It was desribed in 1828[72] as follows:

- The internal decorations were by Francis Cleyne: and a very favourable idea of the artist's abilities may be formed by an inspection of the Gilt Room, which remains nearly in its original state. The ceiling was in a grotesque pattern, but fell in more than forty years ago: the wainscot is in compartments, ornamented with crosslets and fleurs-de-lis; charges in the arms of Rich and Cope, whose shields are introduced entire, at the corners of the Room. There are some emblematical figures over the chimneys, which, according to the opinion of Lord Orford, in style and workmanship are not unworthy of Parmegiano. In the same Gilt Room are some well executed busts, the greater number by Nollekens; among others those of Henry, first Lord Holland, William, Duke of Cumberland, and Francis, Duke of Bedford; Don Gaspar Jovellanos, the Emperor Napoleon, Ariosto, Henry the IV. of France, His Majesty George IV., and Charles James Fox. The original mould of the statue of the last named Statesman, executed by Mr. Westmacott, and erected in Bloomsbury Square, stands in the Entrance Hall. The Pictures include portraits of the Lennox, Digby, and Fox families; among which are those of Sir Stephen Fox, by Sir Peter Lely; Henry, Lord Holland, and the Right Hon. C. J. Fox, when a boy, in a groupe with Lady Susan Strangways, and Lady Mary Lennox, by Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Derivatives

The prestige of Holland House extended to British colonies. In 1831 Henry John Boulton, who was born in Holland House, erected a baronial-like home in the city of Toronto. Henry John Boulton had been born in the famous English house, and he commemorated that fact by naming the Toronto home Holland House.[73]

Assessments

...This strange house, which presents an odd mixture of luxury and constraint, of enjoyment both physical and intellectual, with an alloy of small désagréments.... Though everybody who goes there finds something to abuse or ridicule in the mistress of the house, or its ways, all continue to go; all like it more or less; and whenever, by the death of either, it shall come to an end, a vacuum will be made in society which nothing will supply. It is the house of all Europe; the world will suffer by the loss; and it may be said with truth that it will "eclipse the gayety of nations".

Timeline

The following timeline depicts the successive ownership of Holland House by the Rich family, Edwardes family, Fox family, London County Council, Greater London Council, and finally Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Galleries

Holland House in 1815

Holland House in 1815 Holland House in 1847

Holland House in 1847 Holland House in the 1880s

Holland House in the 1880s.jpg) Holland House in 1896

Holland House in 1896 The Gilt room (c 1895)

The Gilt room (c 1895)

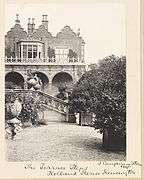

The south frontage of Holland House

The south frontage of Holland House The China Room

The China Room The Dutch Garden

The Dutch Garden A garden with a fountain on the house's west side

A garden with a fountain on the house's west side The north side of the house viewed from its lawn

The north side of the house viewed from its lawn Steps to a garden

Steps to a garden The Gilded Room, or Gilt Chamber

The Gilded Room, or Gilt Chamber The library

The library The arcade, originally part of the old stables

The arcade, originally part of the old stables An arcade of roses

An arcade of roses The main staircase

The main staircase The Swaneries Drawing Room

The Swaneries Drawing Room A garden terrace with steps on the house's east side

A garden terrace with steps on the house's east side

Notes

- ↑ The book of Thorpe's designs is held by Sir John Soane's Museum, containing a ground-plan of the mansion with the identification "Sir Walter Coapes at Kensington, perfected per me I. T."[5]

- ↑ The Survey of Kensington suggests that Fox was able to pay this sum with profits obtained from his office of Paymaster General during the Seven Years' War.[31]

- ↑ In a notebook of engraver George Vertue (designated "A.b" [65]), who compiled a history of art in the country, he records "Kensington, 23 March 1629. Nicholas Stone undertakes to [make] for the Earl of Holland 2 Peeres of good Portland stone to hang a pair of great wooden gates on for £100."[66][64]

Citations

- ↑ Princess of Liechtenstein, 1874, p.175

- ↑ coord|51|30|9|N|0|12|9|W|

- ↑ Neale, John Preston, Views of the Seats of Noblemen and Gentlemen, in England, Wales ..., Volume 4, 1828

- ↑ Designated 29 Jul 1949, no.1267135

- ↑ Sanders (1908), p. 6.

- ↑ Walford (1878), pp. 161-177.

- 1 2 3 Mitton (1903).

- ↑ Birch (1848), p. 75.

- ↑ Birch (1848), p. 205.

- ↑ Webb (1921), pp. 292-296.

- ↑ Walford, Edward (1878). "Holland House and its history - Old and New London: Volume 5 (pp. 161-177)". British History Online. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ↑ George Walter Thornbury, Old and New London: a Narrative of its History, its People, and its Places (1873–74, 2 Vols.) Continued in an undated edition of 1878 in 6 volumes, the last four being by Edward Walford

- ↑ Historic Royal Palaces (2012).

- ↑ Macaulay (1848), p. 63.

- ↑ Faulkner, Thomas, History and Antiquities of Kensington, London, 1820, p.81

- ↑ Walford

- ↑ Faulkner, p.82

- ↑ Faulkner, p.82

- ↑ Walford

- ↑ Walford states monument to 7th Earl of Warwick, but 8th Earl of Warwick has his own inscription on the top pedimented tablet beneath the Rich arms

- ↑ 'The Holland Estate: To 1874', in Survey of London: Volume 37, Northern Kensington, ed. F H W Sheppard (London, 1973), pp. 101-126

- ↑ Montague-Smith, P.W. (ed.), Debrett's Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, Kelly's Directories Ltd, Kingston-upon-Thames, 1968, p.627

- ↑ History of Parliament biography

- ↑ History of Parliament biography

- ↑ History of Parliament biography

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington

- ↑ Survey of London

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington

- ↑ Survey of London, The Holland Estate: To 1874

- ↑ History of Parliament biography of William Edwardes, 1st Baron Kensington

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sheppard (1973).

- ↑ Survey of London

- ↑ Survey of London

- ↑ Survey of London

- ↑ Text of blue plaque on railings to east of Holland House

- ↑ Ridley, Jane, Holland House: A History of London's Most Celebrated Salon, by Linda Kelly, review published in The Spectator, 6 April 2013

- ↑ Liechtenstein, Princess Marie, Holland House, 2 Vols., London, 1874, p.143

- 1 2 ODNB (2004).

- ↑ https://www.thehistoryguide.co.uk/the-holland-house-set/

- ↑ https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/group/1186/Holland%20House%20set

- ↑ Survey of London

- ↑ Survey of London, map dated 1894 shows the entrance at the east

- ↑ Liechtenstein, Princess Marie, Holland House, Vol.1, London, 1874, p.167

- ↑ Liechtenstein, Princess Marie, Holland House, Vol.1, London, 1874, pp.167-72

- ↑ Liechtenstein, p.216

- ↑ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37/pp126-150

- ↑ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37/pp126-150

- ↑ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37/pp126-150

- ↑ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37/pp126-150

- ↑ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/dorset/vol2/pp48-53

- ↑ MacCarthy (2006), pp. 143-144.

- ↑ Mitford (2010), p. 97.

- ↑ Historic England (2015).

- ↑ Victorian Society (2013).

- ↑ https://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol37/pp126-150

- ↑ http://www.waellis.cms-dev.co.uk/Ilchester-Estates

- ↑ Independent Newspaper, 17 July 1999, Millionaire blocks nature reserve in hunt ban protest

- ↑ Kidd, Charles, Debrett's Peerage & Baronetage 2015 Edition, London, 2015, p.P485, Viscount Galway

- ↑ https://www.dorsetcountrylettings.co.uk/residential/

- ↑ https://storiesthatsell.co.uk/2012/10/wealth-what-is-it-to-you/

- ↑ Forbes (1833), p. 246.

- ↑ Hogg (1853), p. 5.

- ↑ Salisbury (1808), p. 93.

- 1 2 Spiers (1919), p. 8.

- ↑ Lindsay (1997), p. 242.

- ↑ Vertue (1713).

- 1 2 Nolan & Starren (2010).

- ↑ Faulkner, p.85

- ↑ Faulkner, p.85

- ↑ Image published in Faulkner, Thomas, History and Antiquities of Kensington’’, London, 1820, between pp.84-5

- ↑ Harper's (1877), pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Neale, John Preston

- ↑ Peppiatt, Liam. "Chapter 3: The History of Holland House". Landmarks of Toronto Revisited. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ↑ Greville (1887), p. 126.

Further reading

- Fox-Strangways, Giles (6th Earl of Ilchester), The House of the Hollands 1605-1820, London, 1937

- Fox-Strangways, Giles (6th Earl of Ilchester), Chronicles of Holland House, 1820-1900, London, 1937

- Fox-Strangways, Giles (6th Earl of Ilchester), Catalogue of pictures belonging to the Earl of Ilchester at Holland House, London, 1904

- Liechtenstein, Princess Marie, Holland House, 2 Vols., London, 1874. Illustrated with 38 mounted woodbury-type prints; engravings, lithographs, etc. The author was "Mary Fox", the adopted daughter of Henry Fox, 4th Baron Holland (1802-1859), of Holland House.

References

- Allen, Elizabeth (September 2009). "Cope, Sir Walter (1553?–1614)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6257. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- Birch, Thomas; Williams, Robert Folkestone (1848). The Court and times of James the First: illustrated by authentic and confidential letters, from various public and private collections. 1. London: Henry Colburn. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- Forbes, James; Russell Bedford, John (1833). Hortus Woburnensis, A Descriptive Catalogue of upwards of Six Thousand Ornamental Plants Cultivated at Woburn Abbey. J. Ridgway.

- Greville, Charles (1887). "Chapter XIX". The Greville Memoirs: A Journal of the Reigns of King George IV. and King William IV. 2. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- "Elizabethan and later English furniture". Harper's New Monthly Magazine. 56 (331). December 1877. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- Historic England. "Holland House (1267135)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2015-07-09.

- "Origins: From Jacobean mansion to Kensington Palace". Historic Royal Palaces. 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- Hogg, Robert (1853). The Dahlia; Its History and Cultivation. Groombidge and Sons.

- Lindsay, Alexander (1997). Index of English Literary Manuscripts. 3, John Gay—Ambrose Philips. London: Mansell Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7201-2283-X.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1848). "XI". The History Of England From the Accession of James II. III. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Mitton, Geraldine Edith (1903). "The Kensington District". In Sir Walter Besant. The Fascination of London. London: Adam & Charles Black. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Nolan, David; Starren, Caroline (2010). "On Public View: A journey around the sculpture of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- Salisbury, R. A. (1808-04-05). "Observations on the different Species of Dahlia, and the best Method of Cultivating them in Britain". Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London. London: W. Bulmer & Co. 1.

- Sanders, Lloyd Charles (1908). The Holland House Circle. London: Methuen & Co. Retrieved 2012-12-01.

- Sheppard, F.H.W. (1973). "The Holland Estate: To 1874". Survey of London: volume 37: Northern Kensington. British History Online. Retrieved 2012-10-20.

- Spiers, Walter Lewis (1919). Finberg, A.J., ed. "Notes on the life of Nicholas Stone". The Walpole Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 7, The Note-book and Account-book of Nicholas Stone, Master Mason to James I and Charles I. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- Vertue, George (1713). Common-place books of G. Vertue. 2. Add MS 23068-23074. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- Walford, Edward (1878). "Holland House, and its Historical Associations". Old and New London. 5. British History Online. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- Webb, E.A. (1921). "The parish: Descendants of Rich and the advowson". The records of St. Bartholomew's priory [and] St. Bartholomew the Great, West Smithfield. 2. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

- "Listed buildings". The Victorian Society. Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- Fiona MacCarthy (5 October 2006). Last Curtsey: The End of the Debutantes. Faber & Faber. pp. 143–144. ISBN 978-0571228591.

- Deborah Mitford (9 November 2010). Wait for Me!: Memoirs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 97. ISBN 978-0374207687.

External links

Media

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holland House. |

- Map of the building (PDF) by Ordnance Survey for the house's entry in Historic England's list of buildings

- Archive film from Pathé News showing the ruins of Holland House after its destruction in the Blitz.

- An iconic photograph of men reading books in the largely undamaged library after the bombing. (Alternative versions: 1, 2)

- Photos from 1952, when the house was sold to the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, showing the damaged interior of the house, and workers clearing rubble.

- Photographic gallery of the current appearance of the building

Websites