History of cannon

| Part of a series on |

| Cannon |

|---|

|

| History |

| Operation |

| By country |

| By type |

The history of the cannon spans several hundred years. The cannon was invented in China as early as the 12th century and traces its development from the fire lance, the ancestor of cannons and firearms. They were among the earliest forms of gunpowder artillery, and over time replaced siege engines—among other forms of aging weaponry—on the battlefield. Their use was first documented in the Middle East in the 13th century, and the first cannon in Europe were probably used in Iberia, during the wars amongst Christians and Muslim kingdoms in Spain, in the 13th century. English cannon were first used during the Hundred Years' War, at the Battle of Crécy, in 1346. It was during this period, the Middle Ages, that cannon became standardized, and more effective in both the anti-infantry and siege roles. After the Middle Ages, most large cannon were abandoned, in favor of greater numbers of lighter, more maneuverable pieces. In addition, new technologies and tactics were developed, making most defenses obsolete; this led to the construction of star forts, specifically designed to withstand bombardment from artillery.

Cannon also transformed naval warfare: the Royal Navy, in particular, took advantage of their firepower. As rifling became more commonplace, the accuracy of cannon was significantly improved, and they became deadlier than ever, especially to infantry. In World War I, a considerable majority of all deaths were caused by cannon; they were also used widely in World War II. Most modern cannon are similar to those used in the Second World War, including autocannon—with the exception of naval guns, which are now significantly smaller in caliber.

Development in China

The cannon appeared in China during the 12th century,[2] probably as a development of the fire-lance, a short ranged weapon combining a gunpowder-filled tube and a polearm of some kind.[3] Co-viative projectiles such as iron scraps or porcelain shards were placed in fire lance barrels at some point,[4] and eventually, the paper and bamboo materials of fire lance barrels were replaced by metal.[5] The earliest known depiction of a cannon is a sculpture from the Dazu Rock Carvings in Sichuan, dated to 1128, that portrays a figure carrying a vase-shaped bombard, firing flames and a cannonball.[2] The oldest surviving gun bearing a date of production is the Xanadu gun, dated to 1298.[6] Other specimens have been dated to even earlier periods, such as the Heilongjiang hand cannon, to 1288, and the Wuwei Bronze Cannon, to 1227. However they contain no inscriptions.

The Heilongjiang hand cannon dated 1288 was found in Yuan dynasty Manchuria and has a muzzle bore diameter of 2.5 cm (1 in); another specimen, dated to 1332, has a muzzle bore diameter of 10.5 cm (4 in).[1][7] In his 1341 poem, The Iron Cannon Affair, one of the first accounts of the use of gunpowder artillery in China, Xian Zhang wrote that a cannonball fired from an eruptor could "pierce the heart or belly when it strikes a man or horse, and can even transfix several persons at once."[8]

Joseph Needham suggests that the proto-shells described in the Huolongjing may be among the first of their kind.[1] The Chinese also mounted over 3,000 bronze and iron cast cannon on the Great Wall of China, to defend themselves from the Mongols. The weapon was later taken up by both the Mongol conquerors. Chinese soldiers fighting under the Mongols appear to have used hand cannon in Manchurian battles during 1288, a date deduced from archaeological findings at battle sites.[9]

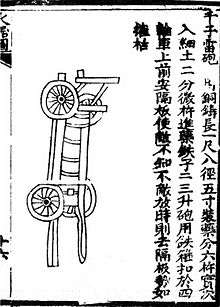

Early Chinese artillery had vase-like shapes. This includes the "long range awe inspiring" cannon dated from 1350 and found in the 14th century Ming Dynasty treatise Huolongjing.[10] With the development of better metallurgy techniques, later cannons abandoned the vase shape of early Chinese artillery. This change can be seen in the bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon," an early example of field artillery.[11]

The Red Turban Rebellion saw the application of early, arrow-firing cannon to both siege and naval warfare in the Southern area of conflict. Following the ascendancy of the Ming Dynasty, cannon were restricted at first to operations pacifying the southern border, including a resounding victory over a band of war-elephants in the 1380s. Cannon made their way to the northern border by 1414, where their noise had great effect on the Oirats, in addition to reportedly killing several hundred Mongols.[5]

In the 1593 Siege of Pyongyang, 40,000 Ming troops deployed a variety of cannon to bombard an equally large Japanese army. Despite both forces having similar numbers, the Japanese were defeated in one day, due to the Ming advantage in firepower. Throughout the Seven Year War in Korea, the Chinese coalition used artillery widely, in both land and naval battles.[12]

Islamic world

According to historian Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, during the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, the Mamluks used a cannon against the Mongols. He claims that this was "the first cannon in history" and used a gunpowder formula almost identical to the ideal composition for explosive gunpowder. He also argues that this was not known in China or Europe until much later.[13][14] Hassan further claims that the earliest textual evidence of cannon is from the middle east, based on earlier originals which report hand-held cannon being used by the Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.[13] However Hassan's claims have been refuted by other historians such as David Ayalon, Iqtidar Alam Khan, Joseph Needham, Tonio Andrade, and Gabor Ágoston. Khan argues that it was the Mongols who introduced gunpowder to the Islamic world,[15] and believes cannons only reached Mamluk Egypt in the 1370s.[16] According to Needham, the term midfa, dated to textual sources from 1342 to 1352, did not refer to true hand-guns or bombards, and contemporary accounts of a metal-barrel cannon in the Islamic world do not occur until 1365[17] Similarly, Andrade dates the textual appearance of cannon in middle eastern sources to the 1360s.[18] Gabor Ágoston and David Ayalon believe the Mamluks had certainly used siege cannon by the 1360s, but earlier uses of cannon in the Islamic World are vague with a possible appearance in the Emirate of Granada by the 1320s and 1330s, however evidence is inconclusive.[19][18]

Ibn Khaldun reported the use of cannon as siege machines by the Marinid sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf at the siege of Sijilmasa in 1274.[13][20] The passage by Ibn Khaldun on the Marinid Siege of Sijilmassa in 1274 occurs as follows: "[ The Sultan] installed siege engines … and gunpowder engines …, which project small balls of iron. These balls are ejected from a chamber … placed in front of a kindling fire of gunpowder; this happens by a strange property which attributes all actions to the power of the Creator."[21] However the source is not contemporary and was written a century later around 1382. Its interpretation has been rejected as anachronistic by historians, notably Ágoston and Peter Purton who urge caution regarding claims of Islamic firearms use in the 1204-1324 period as late medieval Arabic texts used the same word for gunpowder, naft, as they did for an earlier incendiary, naphtha.[22][19]

References to early use of firearms in Islamdom (1204, 1248, 1274, 1258-60, 1303 and 1324) must be taken with caution since terminology used for gunpowder and firearms in late medieval Arabic sources is confused. Furthermore, most of these testimonies are given by later chroniclers of the fifteenth century whose use of terminology may have reflected their own time rather than that of the events they were writing about.[19]

— Gabor Ágoston

Ottoman artillery was certainly introduced by Sultan Mehmed I, the first contemporary record which mention the Ottoman cannons is dated back to 1424, it is related to the defending of Antalya.[23] Super-sized bombards were used by the troops of Mehmed II to capture Constantinople, in 1453. Jim Bradbury argues that Urban, a Hungarian cannon engineer, introduced this cannon from Central Europe to the Ottoman realm.[24] According to Paul Hammer, however, it could have been introduced from other Islamic countries which had earlier used cannons.[20] It could fire heavy stone balls a mile, and the sound of their blast could reportedly be heard from a distance of 10 miles (16 km).[24]

A piece of slightly later date, the Dardanelles Gun (see picture), was cast in bronze and made in two parts: the chase and the breech, which, together, weighed 18.4 tonnes.[25] The two parts were screwed together using levers to facilitate the work. Created by Munir Ali in 1464,[26] the Dardanelles Gun was still present for duty more than 300 years later in 1807, when a Royal Navy force appeared and commenced the Dardanelles Operation. Turkish forces loaded the ancient relics with propellant and projectiles, then fired them at the British ships. The British squadron suffered 28 dead through this bombardment.[27]

Medieval Europe

The earliest European references to gunpowder are found in Roger Bacon's Opus Majus from 1267.[28][29]

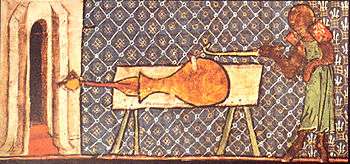

The first metal cannon was the pot-de-fer. Loaded with an arrow-like bolt that was probably wrapped in leather to allow greater thrusting power, it was set off through a touch hole with a heated wire. This weapon, and others similar, were used by both the French and English, during the Hundred Years' War, when cannon saw their first real use on the European battlefield.[30] Even then, cannon were still a relatively rare weapon.

"Ribaldis," which shot large arrows and simplistic grapeshot, were first mentioned in the English Privy Wardrobe accounts during preparations for the Battle of Crécy, between 1345 and 1346.[31] The Florentine Giovanni Villani recounts their destructiveness, indicating that by the end of the battle, "the whole plain was covered by men struck down by arrows and cannon balls."[31] Similar cannon were also used at the Siege of Calais, in the same year, although it was not until the 1380s that the "ribaudekin" clearly became mounted on wheels.[31]

The first cannon appeared in Russia around 1380, though they were used only in sieges, often by the defenders.[32] Around the same period, the Byzantine Empire began to accumulate its own cannon to face the Ottoman threat, starting with medium-sized cannon 3 feet (0.91 m) long and of 10 in caliber.[33] The first definite use of artillery in the region was against the Ottoman siege of Constantinople, in 1396, forcing the Ottomans to withdraw.[33] They acquired their own cannon, and laid siege to the Byzantine capital again, in 1422, using "falcons", which were short but wide cannon. Before the siege of Constantinople, it was known that the Ottomans had the ability to cast medium-sized cannons, but the range of some pieces they were able to field far surpassed the defenders' expectations. Instrumental to this Ottoman advancement in arms production was a somewhat mysterious figure by the name of Orban (Urban), a Hungarian (though some suggest he was German).[34] One cannon designed by Orban was named "Basilica" and was 27 feet (8.2 m) long, and able to hurl a 600 lb (272 kg) stone ball over a mile (1.6 km).[35]

The master founder initially tried to sell his services to the Byzantines, who were unable to secure the funds needed to hire him. Orban then left Constantinople and approached Mehmed II, claiming that his weapon could blast 'the walls of Babylon itself'. Given abundant funds and materials, the Hungarian engineer built the gun within three months at Edirne, from which it was dragged by sixty oxen to Constantinople. In the meantime, Orban also produced other cannons instrumental for the Turkish siege forces.[36]

Orban's cannon had several drawbacks however: it took three hours to reload; cannonballs were in very short supply; and the cannon is said to have collapsed under its own recoil after six weeks (this fact however is disputed,[37] being reported only in the letter of Archbishop Leonardo di Chio[38] and in the later and often unreliable Russian chronicle of Nestor Iskander).[39] Having previously established a large foundry about 150 miles (240 km) away, Mehmed now had to undergo the painstaking process of transporting his massive artillery pieces. Orban's giant cannon was said to have been accompanied by a crew of 60 oxen and over 400 men.[34]

Early modern period

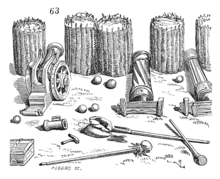

By the 16th century, cannon were made in a great variety of lengths and bore diameters, but the general rule was that the longer the barrel, the longer the range. Some cannon made during this time had barrels exceeding 10 ft (3.0 m) in length, and could weigh up to 20,000 pounds (9,100 kg). Consequently, large amounts of gunpowder were needed, to allow them to fire stone balls several hundred yards.[41] By mid-century, European monarchs began to classify cannon to reduce the confusion. Henry II of France opted for six sizes of cannon,[42] but others settled for more; the Spanish used twelve sizes, and the English sixteen.[43][44] Better powder had been developed by this time as well. Instead of the finely ground powder used by the first bombards, powder was replaced by a "corned" variety of coarse grains. This coarse powder had pockets of air between grains, allowing fire to travel through and ignite the entire charge quickly and uniformly.[45]

The end of the Middle Ages saw the construction of larger, more powerful cannon, as well their spread throughout the world. As they were not effective at breaching the newer fortifications resulting from the development of cannon, siege engines—such as siege towers and trebuchets—became less widely used. However, wooden "battery-towers" took on a similar role as siege towers in the gunpowder age—such as that used at siege of Kazan in 1552, which could hold ten large-caliber cannon, in addition to 50 lighter pieces.[46] Another notable effect of cannon on warfare during this period was the change in conventional fortifications. Niccolò Machiavelli wrote, "There is no wall, whatever its thickness that artillery will not destroy in only a few days."[47] Although castles were not immediately made obsolete by cannon, their use and importance on the battlefield rapidly declined.[48] Instead of majestic towers and merlons, the walls of new fortresses were thicker, angulated, and sloped, while towers became lower and stouter; increasing use was also made of earthen, brick, and stone breastworks and redoubts. These new defenses became known as "star forts," after their characteristic shape.[48] A few of these featured cannon batteries, such as the Tudors' Device Forts, in England.[48] Star forts soon replaced castles in Europe, and, eventually, those in the Americas, as well.[49]

By end of the 15th century, several technological advancements were made, making cannon more mobile. Wheeled gun carriages and trunnions became common, and the invention of the limber further facilitated the transportation of artillery.[50] As a result, field artillery became viable, and began to emerge, often used alongside the larger cannon intended for sieges.[50][51] The better gunpowder, improved, cast-iron projectiles, and the standardization of calibers meant that even relatively light cannon could be deadly.[50] In The Art of War, Niccolò Machiavelli observed that "It is true that the arquebuses and the small artillery do much more harm than the heavy artillery."[47] This was the case at Flodden, in 1513: the English field guns outpaced the Scottish siege artillery, firing twice, or even thrice, as many rounds.[52] Despite the increased maneuverability, however, cannon were still much slower than the rest of the army: a heavy English cannon required 23 horses to transport, while a culverin, nine, yet, even with this many animals transporting them, they still moved at a walking pace. Due to their relatively slow speed, and lack of organization, discipline, and tactics, the combination of pike and shot still dominated the battlefields of Europe.[53]

Innovations continued, notably the German invention of the mortar, a thick-walled, short-barreled gun that blasted shot upward at a steep angle. Mortars were useful for sieges, as they could fire over walls and other defenses.[54] This cannon found more use with the Dutch, who learned to shoot bombs filled with powder from them. However, setting the bomb fuse in the mortar was a problem. "Single firing" was the first technique used to set the fuse, where the bomb was placed with the fuse down against the propelling charge. This practice often resulted in the fuse being blown into the bomb, causing it to blow up in front of the mortar. Because of this danger, "double firing" was developed, where the fuse was turned up and the gunner lighted the fuse and the touch hole simultaneously. This, however, required much skill and timing, and was especially dangerous when the gun failed to fire, leaving a lighted bomb in the barrel. Not until 1650 was it accidentally discovered that double-lighting was a superfluous process: the heat of firing was enough to light the fuse.[55]

Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden emphasized the use of light cannon and mobility in his army, and created new formations and tactics that revolutionized artillery. He discontinued using all 12 pounder—or heavier—cannon as field artillery, preferring, instead, to use cannon that could be manned by only a few men. One gun, called the "leatheren," could be serviced by only two persons, but was abandoned, replaced by 4 pounder and 9 pounder demi-culverins. These could be operated by three men, and pulled by only two horses. Also, Adolphus's army was the first to use a special cartridge that contained both powder and shot, which sped up loading, and therefore increased the rate of fire.[56] Additionally, he pioneered the use of canister shot against infantry, which was essentially a can, filled with musket balls.[57] At the time, for each thousand infantrymen, there was one cannon on the battlefield; Gustavus Adolphus increased the number of cannon in his army so dramatically, that there were six cannon for each one thousand infantry. Each regiment was assigned two pieces, though he often decided to arrange his artillery into batteries, instead. These were to decimate the enemy's infantry, while his cavalry outflanked their heavy guns.[58] At the Battle of Breitenfeld, in 1631, Adolphus proved the effectiveness of the changes made to his army, in particular his artillery, by defeating Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly. Although severely outnumbered, the Swedes were able to fire between three and five times as many volleys of artillery without losing ground, due to their infantry's linear formations. Battered by cannon fire, and low on morale, Tilly's men broke rank, and fled.[59]

Around this time also came the idea of aiming the cannon to hit a target. Gunners controlled the range of their cannon by measuring the angle of elevation, using a "gunner's quadrant." Cannon did not have sights, therefore, even with measuring tools, aiming was still largely guesswork.[60]

In the latter half of the 17th century, the French engineer Vauban introduced a more systematic and scientific approach to attacking gunpowder fortresses, in a time when many field commanders "were notorious dunces in siegecraft."[61] Careful sapping forward, supported by enfilading ricochet fire, was a key feature of this system, and it even allowed Vauban to calculate the length of time a siege would take.[61] He was also a prolific builder of star forts, and did much to popularize the idea of "depth defense" in the face of cannon.[62] These principles were followed into the mid-19th century, when changes in armaments necessitated greater depth defense than Vauban had provided for. It was only in the years prior to World War I that new works began to break radically away from his designs.[63]

18th and 19th centuries

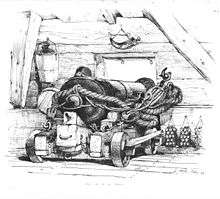

The lower tier of 17th-century English ships of the line were usually equipped with demi-cannon, guns that fired a 32-pound (15 kg) solid shot, and could weigh up to 3,400 pounds (1,500 kg).[64] Demi-cannon were capable of firing these heavy metal balls with such force, that they could penetrate more than a meter of solid oak, from a distance of 90 m (300 ft), and could dismast even the largest ships at close range.[65] Full cannon fired a 42 lb (19 kg) shot, but were discontinued by the 18th century, as they were too unwieldy. By the end of the century, principles long adopted in Europe specified the characteristics of the Royal Navy's cannon, as well as the acceptable defects, and their severity. The United States Navy tested guns by measuring them, firing them two or three times,—termed "proof by powder"—and using pressurized water to detect leaks.[66]

The carronade was adopted by the Royal Navy in 1779; the lower muzzle velocity of the round shot when fired from this cannon was intended to create more wooden splinters when hitting the structure of an enemy vessel, as they were believed to be deadly.[67] The carronade was much shorter, and weighed between a third to a quarter less than an equivalent long gun; for example, a 32 pounder carronade weighed less than a ton, compared with a 32 pounder long gun, which weighed over 3 tons. The guns were, therefore, easier to handle, and also required less than half as much gunpowder, allowing fewer men to crew them.[68] Carronades were manufactured in the usual naval gun calibers,[69] but were not counted in a ship of the line's rated number of guns. As a result, the classification of Royal Navy vessels in this period can be misleading, as they often carried more cannon than were listed.

In the 1810s and 1820s, greater emphasis was placed on the accuracy of long-range gunfire, and less on the weight of a broadside. The carronade, although initially very successful and widely adopted, disappeared from the Royal Navy in the 1850s, after the development of jacketed steel cannon, by William George Armstrong and Joseph Whitworth. Nevertheless, carronades were used in the American Civil War.[67][70]

The Great Turkish Bombards of the Siege of Constantinople, after being on display for four centuries, were used to battle a British fleet in 1807, in the Dardanelles Operation. The artillery hit a British ship with two 700 lb (320 kg) cannonballs, killing 60 sailors; in total, the cannon claimed over 100 lives, prompting the British to retreat. In 1867, Sultan Abdul Aziz gave Victoria of the United Kingdom the 17-ton "Dardanelles Gun," one of the cannon used at the siege of Constantinople.[71]

In contrast to these antiquated weapons, Western cannon during the 19th century became larger, more destructive, more accurate, and could fire at longer range. One example is the American 3 in (76 mm) wrought-iron, muzzle-loading howitzer, used during the American Civil War, which had an effective range of over 1.1 mi (1.8 km). Another is the smoothbore 12 pounder Napoleon, which was renowned for its sturdiness, reliability, firepower, flexibility, relatively light weight, and range of 1,700 m (5,600 ft).[72]

Cannon were crucial in Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power, and continued to play an important role in his army in later years.[73] During the French Revolution, the unpopularity of the Directory led to riots and rebellions. When over 25,000 of these royalists—led by General Danican—assaulted Paris, Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras was appointed to defend the capital; outnumbered five to one and disorganized, the Republicans were desperate.[74] When Napoleon arrived, he reorganized the defenses, while realizing that without cannon, the city could not be held. He ordered Joachim Murat to bring the guns from the Sablons artillery park; the Major and his cavalry fought their way to the recently captured cannon, and brought them back to Napoleon. When Danican's poorly trained men attacked, on 13 Vendémiaire, 1795—5 October 1795, in the calendar used in France, at the time—Napoleon ordered his cannon to fire grapeshot into the mob,[75] an act that became known as the "whiff of grapeshot"[76]. The slaughter effectively ended the threat to the new government, while, at the same time, made Bonaparte a famous—and popular—public figure.[75][77] Among the first generals to recognize that artillery was not being used to its full potential, Napoleon often massed his cannon into batteries, and introduced several changes into the French artillery, improving it significantly, and making it among the finest in Europe.[78][79] Such tactics were successfully used by the French, for example, at the Battle of Friedland, when sixty-six guns fired a total of 3,000 roundshot, and 500 grapeshot,[78][80] inflicting severe casualties on the Russian forces, whose losses numbered over 20,000 killed and wounded, in total.[81] At the Battle of Waterloo—Napoleon's final battle—the French army had many more artillery pieces than either the British or Prussians. As the battlefield was muddy, recoil caused cannon to bury themselves into the ground after firing, resulting in slow rates of fire, as more effort was required to move them back into an adequate firing position;[82] also, roundshot did not ricochet with as much force from the wet earth.[83] Despite the drawbacks, sustained artillery fire proved deadly during the engagement, especially during the French cavalry attack.[84] The British infantry, having formed infantry squares, took heavy losses from the French guns, while their own cannon fired at the cuirassiers and lancers, when they fell back to regroup. Eventually, the French ceased their assault, after taking heavy losses from the British cannon and musket fire.[85]

The practice of rifling—casting spiraling lines inside the cannon's barrel—was applied to artillery more frequently by 1855, as it gave cannon gyroscopic stability, which improved their accuracy. One of the earliest rifled cannon was the Armstrong gun—also invented by William George Armstrong—which boasted significantly improved range, accuracy, and power than earlier weapons. The projectile fired from the Armstrong gun could reportedly pierce through a ship's side, and explode inside the enemy vessel, causing increased damage, and casualties.[86] The British military adopted the Armstrong gun, and was impressed; the Duke of Cambridge even declared that it "could do everything but speak."[87] Despite being significantly more advanced than its predecessors, the Armstrong gun was rejected soon after its integration, in favor of the muzzle-loading pieces that had been in use before.[88] While both types of gun were effective against wooden ships, neither had the capability to pierce the armor of ironclads; due to reports of slight problems with the breeches of the Armstrong gun, and their higher cost, the older muzzle-loaders were selected to remain in service, instead.[89] Realizing that iron was more difficult to pierce with breech-loaded cannon, Armstrong designed rifled muzzle-loading guns,[90] which proved successful; The Times reported: "even the fondest believers in the invulnerability of our present ironclads were obliged to confess that against such artillery, at such ranges, their plates and sides were almost as penetrable as wooden ships."[91]

The superior cannon of the Western world brought them tremendous advantages in warfare. For example, in the Opium War in China, during the 19th century, British battleships bombarded the coastal areas and fortifications from afar, safe from the reach of the Chinese cannon. Similarly, the shortest war in recorded history, the Anglo-Zanzibar War of 1896, was brought to a swift conclusion by shelling from British battleships.[92] The cynical attitude towards recruited infantry in the face of ever more powerful field artillery is the source of the term cannon fodder, first used by François-René de Chateaubriand, in 1814;[93] however, the concept of regarding soldiers as nothing more than "food for powder" was mentioned by William Shakespeare as early as 1598, in Henry IV, Part 1.[94]

20th and 21st centuries

Cannon in the 20th and 21st centuries are usually divided into sub-categories, and given separate names. Some of the most widely used types of modern cannon are howitzers, mortars, guns, and autocannon, although a few superguns—extremely large, custom-designed cannon—have also been constructed. Modern artillery is used in a variety of roles, depending on its type. According to NATO, the general role of artillery is to provide fire support, which is defined as "the application of fire, coordinated with the maneuver of forces to destroy, neutralize, or suppress the enemy."[95]

When referring to cannon, the term gun is often used incorrectly. In military usage, a gun is a cannon with a high muzzle velocity and comparatively flat trajectory,[96] as opposed to other types of artillery, such as howitzers or mortars, which have lower muzzle velocities, and usually fire indirectly.[97][98]

Artillery

By the early 20th century, infantry weapons became more powerful and accurate, forcing most artillery away from the front lines. Despite the change to indirect fire, cannon still proved highly effective during World War I, causing over 75% of casualties.[99] The onset of trench warfare after the first few months of World War I greatly increased the demand for howitzers, as they fired at a steep angle, and were thus better suited than guns at hitting targets in trenches. Furthermore, their shells carried larger amounts of explosives than those of guns, and caused considerably less barrel wear. The German army took advantage of this, beginning the war with many more howitzers than the French.[100] World War I also marked the use of the Paris Gun, the longest-ranged gun ever fired. This 200 mm (8 in) caliber gun was used by the Germans to bombard Paris, and was capable of hitting targets more than 122 km (76 mi) away.[101]

The Second World War sparked new developments in cannon technology. Among them were sabot rounds, hollow-charge projectiles, and proximity fuses, all of which were marginally significant.[102] The World War II-era "legend" of the dreaded German 88 mm gun was launched during the Battle of Arras on May 21, 1940 when Generalmajor Erwin Rommel first ordered their use against Allied armor, devastating British Matilda II tanks, a well-armored design.[103] The proximity fuse emerged on the battlefields of Europe in late December 1944.[104] They became known as the American artillery's "Christmas present" for the German army, and were employed primarily in the Battle of the Bulge. Proximity fuses were effective against German personnel in the open, and hence were used to disperse their attacks. Also used to great effect in anti-aircraft projectiles, proximity fuses were used in both the European and Pacific Theaters of Operations, against V-1 flying bombs and kamikaze planes, respectively.[105] Anti-tank guns were also tremendously improved during the war: in 1939, the British used primarily 2 pounder and 6 pounder guns. By the end of the war, 17 pounders had proven much more effective against German tanks, and 32 pounders had entered development.[106][107] Meanwhile, German tanks were continuously upgraded with better main guns, in addition to other improvements. For example, the Panzer III was originally designed with a 37 mm gun, but was mass-produced with a 50 mm cannon.[108] To counter the threat of the Russian T-34s, another, more powerful 50 mm gun was introduced,[108] only to give way to a larger 75 mm cannon.[109] Despite the improved guns, production of the Panzer III was ended in 1943, as the tank still could not match the T-34, and was, furthermore, being replaced by the Panzer IV and Panther tanks.[110] Following the 88 mm FlaK 36's initial anti-tank success in 1940 and through the German forces' battles in North Africa and the Soviet Union, in 1944, its improved tank-mounted version, the 8.8 cm KwK 43,—and its multiple variations—entered service, used by the Wehrmacht, and was adapted to be both a tank's main gun, and the PaK 43 anti-tank gun.[111][112] One of the most powerful guns to see service in World War II, it was capable of destroying any Allied tank at very long ranges.[113][114]

Despite being designed to fire at trajectories with a steep angle of descent, howitzers can be fired directly, as was done by the 11th Marine Regiment at the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, during the Korean War. Two field batteries fired directly upon a battalion of Chinese infantry; the Marines were forced to brace themselves against their howitzers, as they had no time to dig them in. The Chinese infantry took heavy casualties, and were forced to retreat.[115]

The tendency to create larger caliber cannon during the World Wars has been reversed in more recent years. The United States Army, for example, sought a lighter, more versatile howitzer, to replace their aging pieces. As it could be towed, the M198 was selected to be the successor to the World War II-era cannon used at the time, and entered service in 1979.[116] Still in use today, the M198 is, in turn, being slowly replaced by the M777 Ultralightweight howitzer, which weighs nearly half as much, and can be transported by helicopter—as opposed to the M198, which requires a C-5 or C-17 to airlift.[116][117] Although land-based artillery such as the M198 are powerful, long-ranged, and accurate, naval guns have not been neglected, despite being much smaller than in the past, and, in some cases, having been replaced by cruise missiles.[118] However, the Zumwalt-class destroyer's planned armament includes the Advanced Gun System (AGS), a pair of 155 mm guns, which fire the Long Range Land-Attack Projectile. The warhead, which weighs 24 pounds (11 kg), has a circular error of probability of 50 m (160 ft), and will be mounted on a rocket, to increase the effective range to 100 nmi (190 km)—a longer range than that of the Paris Gun. The AGS's barrels will be water cooled, and will be capable of firing 10 rounds per minute, per gun. The combined firepower from both turrets will give Zumwalt-class destroyers the firepower equivalent to 18 conventional M-198 howitzers.[119][120] The reason for the re-integration of cannon as a main armament in United States Navy ships is because satellite-guided munitions fired from a gun are far less expensive than a cruise missile, and are therefore a better alternative to many combat situations.[118]

Autocannon

An autocannon is a cannon with a larger caliber than a machine gun, but smaller than that of a field gun. Autocannons have mechanisms to automatically load their ammunition, and therefore have a faster rate of fire than artillery, often approaching—and, in the case of Gatling guns, surpassing—that of a machine gun.[121] The traditional minimum bore for autocannon—indeed, for all types of cannon, as autocannon are the lowest-caliber pieces—has remained 20 mm, since World War II.

Most nations use these rapid-fire cannon on their light vehicles, replacing a more powerful, but heavier, tank gun. A typical autocannon is the 25 mm "Bushmaster" chain gun, mounted on the LAV-25 and M2 Bradley armored vehicles.[122]

Autocannon have largely replaced machine guns in aircraft, due to their greater firepower.[123] The first airborne cannon appeared in World War II, but each airplane could carry only one or two, as cannon are heavier than machine guns, the standard armament. They were variously mounted, often in the wings, but also high on the forward fuselage, where they would fire through the propeller, or even through the propeller hub. Due both to the low number of cannon per aircraft, and the lower rate of fire of cannon, machine guns continued to be used widely early in the war, as there was a greater probability of hitting enemy aircraft.[123] However, as cannon were more effective against more heavily armored bomber aircraft, they were eventually integrated into newer fighters, which usually carried between two and four autocannon. The Hispano-Suiza HS.404, Oerlikon 20 mm cannon, MG FF, and their numerous variants became among the most widely used autocannon in the war. Nearly all modern fighter aircraft are armed with an autocannon, and most are derived from their counterparts from the Second World War.[123] The largest, heaviest, and most powerful airborne cannon used by the military of the United States is the GAU-8/A Avenger Gatling-type rotary cannon;[124] it is surpassed only by the specialized artillery pieces carried on the AC-130 gunship.[125]

Although capable of generating a high volume of fire, autocannon are limited by the amount of ammunition that can be carried by the weapons systems mounting them. For this reason, both the 25 mm Bushmaster and the 30 mm RARDEN are deliberately designed with relatively slow rates of fire, to extend the amount of time they can be employed on a battlefield before requiring a resupply of ammunition. The rate of fire of modern autocannon ranges from 90 rounds per minute, to 1,800 rounds per minute. Systems with multiple barrels—Gatling guns—can have rates of fire of several thousand rounds per minute; the fastest of these is the GSh-6-30K, which has a rate of fire of over 6,000 rounds per minute.[121]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Needham 1986, p. 263–275.

- 1 2 Lu 1988.

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 263-275.

- ↑ Crosby 2002, p. 99.

- 1 2 Chase 2003, p. 31-32.

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 52-53.

- ↑ C.P.Atwood-Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.354

- ↑ Norris, John (2003). Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600. Marlborough: The Crowood Press. p. 11. ISBN 1-86126-615-4.

- ↑ Pacey, Arnold (1990). Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History. MIT Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-262-66072-5.

- ↑ Needham 1987, pp. 314–316

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1987). Science & Civilisation in China, volume 7: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 317–319. ISBN 0-521-30358-3.

- ↑ Archer, Christon I. (2002). World History of Warfare. University of Nebraska Press. p. 211. ISBN 0-8032-4423-1. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- 1 2 3 Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Gunpowder Composition for Rockets and Cannon in Arabic Military Treatises in Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries". Ahmad Y Hassan. Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- ↑ Hassan, Ahmad Y. "Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries". Ahmad Y Hassan. Archived from the original on 27 April 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2007.

- ↑ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996). "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols". Journal of Asian History. 30: 41–5. .

- ↑ Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004). "Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India". Oxford University Press. .

- ↑ Needham 1986, p. 44.

- 1 2 Andrade 2016, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Ágoston 2005, p. 15.

- 1 2 Paul E. J. Hammer (2007), Warfare in Early Modern Europe 1450-1660, page 297, Ashgate Publishing

- ↑ Andrade 2016, p. 334.

- ↑ Purton 2010, p. 108-109.

- ↑ Robert Elgood (1995). Firearms of the Islamic World: In the Tared Rajab Museum, Kuwait. I.B.Tauris. p. 12. ISBN 9781850439639.

- 1 2 Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege. Rochester, New York: Boydell & Brewer. p. 293. ISBN 0-85115-312-7. Retrieved 2008-05-26.

- ↑ Gat, Azar (2006). War in Human Civilization. New York City: Oxford University Press. p. 461. ISBN 0-19-926213-6.

- ↑ Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- ↑ Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228), p. 228

- ↑ Chase 2003, p. 58.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 25.

- ↑ Manucy, p 3

- 1 2 3 Nicolle, David (2000). Crécy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow. Osprey Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-85532-966-9.

- ↑ Nossov, Konstantin (2007). Medieval Russian Fortresses AD 862–1480. Osprey Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-84603-093-2.

- 1 2 Turnbull, Stephan (2004). The Walls of Constantinople AD 413–1453. Osprey Publishing. pp. 39–41. ISBN 1-84176-759-X.

- 1 2 Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. New York: Vintage Books. p. 374.

- ↑ Davis, Paul (1999). 100 Decisive Battles. Oxford. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-19-514366-9.

- ↑ Runciman 1965, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Pertusi, Agostino, ed. (1976). La Caduta di Costantinopoli. Fondazione Lorenzo Valla: Verona. (An anthology of contemporary texts and documents on the fall of Constantinople; includes bibliographies and a detailed scholarly comment).

- ↑ (in Latin) Leonardo di Chio, Letter to Pope Nicholas V, dated 16 August 1453, edited by J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Graeca, 159, 923A–944B.

- ↑ Another expert who was employed by the Ottomans was Ciriaco de' Pizzicolli, also known as Ciriaco of Ancona, a traveler and collector of antiquities.

- ↑ översättning och bearbetning: Folke Günther ... (1996). Guinness Rekordbok (in Swedish). Stockholm: Forum. p. 204. ISBN 91-37-10723-2.

- ↑ Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 270. ISBN 0-313-32433-6.

- ↑ The six sizes are, in order from largest to smallest: the cannon, great culverin, bastard culverin, "legitimate" culverin, falcon, and falconet.

- ↑ They are, from largest to smallest: the cannon royal, cannon, cannon serpentine, bastard cannon, demicannon, pedrero, culverin, basilisk, demiculverin, bastard culverin, saker, minion, falcon, falconet, serpentine, and rabinet.

- ↑ Tunis, Edwin (1999). Weapons: A Pictorial History. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-8018-6229-9.

- ↑ Tunis, p. 88.

- ↑ Nossov, Konstantin (2006). Russian Fortresses, 1480–1682. Osprey Publishing. pp. 53–55. ISBN 1-84176-916-9.

- 1 2 Machiavelli, Niccolò (2005). The Art of War. Chicago, Ill.: University of Chicago Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-226-50046-2.

- 1 2 3 Wilkinson, Philip (9 September 1997). Castles. Dorling Kindersley. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7894-2047-3.

- ↑ Chartrand, René (2006). Spanish Main: 1492–1800. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84603-005-6.

- 1 2 3 Manucy, p. 5.

- ↑ Sadler, John (2006). Flodden 1513: Scotland's Greatest Defeat. Osprey Publishing. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-1-84176-959-2.

- ↑ Sadler, p. 60.

- ↑ Manucy, p. 6.

- ↑ "Encyclopædia Britannica Online – Mortar". Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ↑ Tunis, p. 90.

- ↑ Manucy, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Tunis, p. 96.

- ↑ Manucy, p. 8.

- ↑ Jones, Archer (2001). The Art of War in the Western World. New York City: University of Illinois Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-252-06966-8.

- ↑ Tunis, p. 97.

- 1 2 Griffith, Paddy (2006). The Vauban Fortifications of France. Osprey Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-84176-875-5.

- ↑ Griffith, p 29

- ↑ Griffith, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Stone, George Cameron (1999). A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times. Courier Dover Publications. p. 162. ISBN 0-486-40726-8.

- ↑ Heath, Byron (2005). Discovering the Great South Land. Kenthurst: Rosenberg Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 1-877058-31-9.

- 1 2 Manigault, Edward; Warren Ripley (1996). Siege Train: The Journal of a Confederate Artilleryman in the Defense of Charleston. Charleston, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. p. 83. ISBN 1-57003-127-4.

- ↑ "The Historical Maritime Society". The Historical Maritime Society. 2001. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- ↑ 12, 18, 24, 32, and 42 pounders, but 6 pounder and 68 pounder versions are known.

- ↑ "Carronade". The Historical Maritime Society. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ↑ Wallechinsky, David; Irving Wallace (1975). The People's Almanac. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-04186-1.

- ↑ Hazlett, James C.; Edwin Olmstead; M. Hume Parks (2004). Field Artillery Weapons of the American Civil War (5th ed.). Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. pp. 88–108. ISBN 0-252-07210-3.

- ↑ Conner, Susan P. (2004). The Age of Napoleon. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 12. ISBN 0-313-32014-4. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Asprey, Robert B. (2000). The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte. Basic Books. p. 111. ISBN 0-465-04881-1. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- 1 2 Asprey, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Conner, p. 13.

- ↑ Conner, pp. 12–13.

- 1 2 Baynes, p. 669.

- ↑ Nofi, Albert A. (1998). The Waterloo Campaign: June 1815. Da Capo Press. p. 123. ISBN 0-938289-98-5. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Craik, George L.; Charles MacFarlane (1884). The Pictorial History of England during the reign of George the Third: Being a History of the People, as well as a History of the Kingdom, volume 2. London: Charles Knight. p. 295. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Chandler, David G. (1995). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York City: Simon & Schuster. p. 582. ISBN 0-02-523660-1.

- ↑ Adkin, Mark (2002). The Waterloo Companion. Stackpole Books. p. 283. ISBN 0-8117-1854-9. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Wilkinson-Latham, Robert (1975). Napoleon's Artillery. France: Osprey Publishing. p. 32. ISBN 0-85045-247-3. Retrieved 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Wilkinson-Latham, p. 36.

- ↑ Nofi, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Dickens, Charles (22 April 1859). "All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal": 373. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Bastable, Marshall J. (2004). Arms and the State: Sir William Armstrong and the Remaking of British Naval Power, 1854–1914. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 59. ISBN 0-7546-3404-3. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Ruffell, W. L. "The Gun – Rifled Ordnance: Whitworth". The Gun. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- ↑ Bastable, Marshall J. (2004). Arms and the State: Sir William Armstrong and the Remaking of British Naval Power, 1854–1914. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 94. ISBN 0-7546-3404-3. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Bastable, p. 72.

- ↑ Bastable, p. 73.

- ↑ Young, Mark C. (2002). Guinness Book of World Records, 2002 edition. Bantam Books. p. 112. ISBN 0-553-58378-6.

- ↑ (in French) "De Buonaparte et des Bourbons" – full text in the French Wikisource.

- ↑ Shakespeare, William (1598). Henry IV, Part 1. Part 1, act 4, sc. 2, l. 65-7.

- ↑ AAP-6 NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions (PDF). North Atlantic Treaty Organization. 2007. p. 113. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ "Definition of "Gun"". Merriam-Webster's Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ↑ "Definition of "Howitzer"". Merriam-Webster's Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ↑ "Definition of "Mortar"". Merriam-Webster's Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-03-17.

- ↑ Manucy, p. 20.

- ↑ Gudmundsson, Bruce I. (1993). On Artillery. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 43. ISBN 0-275-94047-0.

- ↑ Young, p. 113.

- ↑ McCamley, Nicholas J. (2004). Disasters Underground. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-022-4.

- ↑ Frieser, K-H (2005). The Blitzkrieg Legend (English trans. ed.). Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. p. 275-276. ISBN 1-59114-294-6.

- ↑ "Radio Proximty (VT) Fuzes". 20 March 2000. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ↑ "Variable Time Fuse Contributed to the Victory of United Nations". Smithsonian Institution. 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-05.

- ↑ Keegan, John (2000). World War II: A Visual Encyclopedia. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 29. ISBN 1-85585-878-9.

- ↑ Rahman, Jason (November 2007). "British Anti-Tank Guns". Avalanche Press. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- 1 2 Green, Michael; Thomas Anderson; Frank Schulz (2000). German Tanks of World War II in Color. Zenith Imprint. p. 46. ISBN 0-7603-0671-0. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ Green, p. 47.

- ↑ Zetterling, Niklas; Anders Frankson (2000). Kursk 1943: A Statistical Analysis. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 0-7146-5052-8.

- ↑ Bradford, George (2007). German Early War Armored Fighting Vehicles. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. p. 3. ISBN 0-8117-3341-6.

- ↑ Playfair, Ian S. O.; T. P. Gleave (1987). The Mediterranean and Middle East. HMSO. p. 257. ISBN 0-11-630946-6.

- ↑ McCarthy, Peter; Mike Syron (2003). Panzerkrieg: The Rise and Fall of Hitler's Tank Divisions. Carroll & Graf Publishers. p. 239. ISBN 0-7867-1264-3. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Jarymowycz, Roman Johann (2001). Tank Tactics: From Normandy to Lorraine. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 115. ISBN 1-55587-950-0. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Russ, Martin (1999). Breakout: The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, Korea 1950. Penguin Books. pp. 383–384. ISBN 0-14-029259-4.

- 1 2 "M198 information". Military.com. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ "M777 information". Military.com. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- 1 2 "Affordable precision". National Defense Magazine. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 2008-03-18.

- ↑ Pike, John (18 February 2008). "DDG-1000 Zumwalt / DD(X) Multi-Mission Surface Combatant". Global Security. Retrieved 2008-03-21.

- ↑ "Raytheon Company: Products & Services: Advanced Gun System (AGS)". Raytheon, Inc. Archived from the original on 19 March 2008. Retrieved 21 March 2008.

- 1 2 Williams, Anthony G. (2000). Rapid Fire. Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd. p. 241. ISBN 1-84037-435-7.

- ↑ "Army Technology – Bradley M2/M3 – Tracked Armoured Fighting Vehicles". Army Technology.com. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- 1 2 3 Dr. Carlo Kopp. "Aircraft cannon". Strike Publications. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- ↑ "GAU-8/A". 442nd Fighter Wing. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ↑ "Information on the GAU-8/A". The Language of Weaponry. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-27.

Bibliography

- Adle, Chahryar (2003), History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in Contrast: from the Sixteenth to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

- Ágoston, Gábor (2005), Guns for the Sultan: Military Power and the Weapons Industry in the Ottoman Empire, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-60391-9

- Agrawal, Jai Prakash (2010), High Energy Materials: Propellants, Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Wiley-VCH

- Andrade, Tonio (2016), The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-13597-7 .

- Archer, Christon I. (2002), World History of Warfare, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-4423-1

- Arnold, Thomas (2001), The Renaissance at War, Cassell & Co, ISBN 0-304-35270-5

- Asprey, Robert B. (2000), The Rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-04881-1

- Bastable, Marshall J. (2004), Arms and the State: Sir William Armstrong and the Remaking of British Naval Power, 1854–1914, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-3404-3

- Baynes, Thomas S. (1888), The Encyclopædia Britannica A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information, volume 2

- Benton, Captain James G. (1862), A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery (2 ed.), West Point, New York: Thomas Publications, ISBN 1-57747-079-6

- Bradbury, Jim (1992), The Medieval Siege, Rochester, New York: Boydell & Brewer, ISBN 0-85115-312-7

- Bradford, George (2007), German Early War Armored Fighting Vehicles, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, ISBN 0-8117-3341-6

- Braun, Wernher Von; Frederick Ira Ordway (1967), History of Rocketry & Space Travel, Thomas Y. Crowell Co., ISBN 0-690-00588-1

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-1878-0 .

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 0-7546-5259-9

- Chandler, David G. (1995), The Campaigns of Napoleon, New York City: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-02-523660-1

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-82274-2 .

- Chartrand, René (29 August 2006), Spanish Main 1492–1800, Random House, ISBN 1-84603-005-6

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-718-0

- Conner, Susan P. (2004), The Age of Napoleon, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32014-4

- Cook, Haruko Taya (2000), Japan At War: An Oral History, Phoenix Press

- Cowley, Robert (1993), Experience of War, Laurel .

- Craik, George L.; Charles MacFarlane (1884), The Pictorial History of England during the Reign of George the Third: Being a History of the People, as well as a History of the Kingdom, volume 2, London: Charles Knight

- Cressy, David (2013), Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder, Oxford University Press

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-79158-8 .

- Curtis, W. S. (2014), Long Range Shooting: A Historical Perspective, WeldenOwen .

- Dickens, Charles (22 April 1859). "All the Year Round: A Weekly Journal".

- Earl, Brian (1978), Cornish Explosives, Cornwall: The Trevithick Society, ISBN 0-904040-13-5 .

- Easton, S. C. (1952), Roger Bacon and His Search for a Universal Science: A Reconsideration of the Life and Work of Roger Bacon in the Light of His Own Stated Purposes, Basil Blackwell

- Ebrey, Patricia B. (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43519-6

- Gat, Azar (2006), War in Human Civilization, New York City: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926213-6

- Grant, R.G. (2011), Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare, DK Publishing .

- Green, Michael; Thomas Anderson; Frank Schulz (2000), German Tanks of World War II in Color, Zenith Imprint, ISBN 0-7603-0671-0

- Griffith, Paddy (2006), The Vauban Fortifications of France, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-875-5

- Gudmundsson, Bruce I. (1993), On Artillery, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-94047-0

- Hadden, R. Lee. 2005. "Confederate Boys and Peter Monkeys." Armchair General. January 2005. Adapted from a talk given to the Geological Society of America on March 25, 2004.

- Halberstadt, Hans (2002), The World's Great Artillery: From the Middle Ages to the Present Day, Barnes & Noble, ISBN 0-7607-3303-1

- Harding, David (1990), Weapons: An International Encyclopedia from 5000 B.C. to 2000 A.D., Diane Publishing Company, ISBN 0-7567-8436-0

- Harding, Richard (1999), Seapower and Naval Warfare, 1650-1830, UCL Press Limited

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2001), "Potassium Nitrate in Arabic and Latin Sources", History of Science and Technology in Islam, retrieved 23 July 2007 .

- Hazlett, James C.; Edwin Olmstead; M. Hume Parks (2004), Field Artillery Weapons of the American Civil War (5th ed.), Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-07210-3

- Heath, Byron (2005), Discovering the Great South Land, Kenthurst, New South Wales: Rosenberg Publishing, ISBN 1-877058-31-9

- Hoffmeyer, Ada Bruhn de. (1972), Arms and Armour in Spain: A Short Survey, Madrid: Instituto de Estudios sobre Armas Antiguas

- Hogg, Ian V.; John H. Batchelor (1978), Naval Gun, Blandford Press, ISBN 0-7137-0905-7

- Holmes, Richard (2002), Redcoat: the British Soldier in the age of Horse and Musket, W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-05211-7

- Jarymowycz, Roman Johann (2001), Tank Tactics: From Normandy to Lorraine, Lynne Rienner Publishers, ISBN 1-55587-950-0

- Hobson, John M. (2004), The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation, Cambridge University Press .

- Johnson, Norman Gardner. "explosive". Encyclopædia Britannica. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Keegan, John (2000), World War II: A Visual Encyclopedia, Sterling Publishing Company, Inc., ISBN 1-85585-878-9

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-03718-6 .

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (1996), "Coming of Gunpowder to the Islamic World and North India: Spotlight on the Role of the Mongols", Journal of Asian History, 30: 41–5 .

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2008), Historical Dictionary of Medieval India, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0-8108-5503-8

- Kinard, Jeff (2007), Artillery An Illustrated History of its Impact

- Knox, Dudley W. (1939), Naval Documents related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers, Volume I, Washington: United States Government Printing Office

- Konstam, Angus (2002), Renaissance War Galley 1470-1590, Osprey Publisher Ltd. .

- Krebs, Robert E. (2004), Groundbreaking Scientific Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32433-6

- Lee, Ernest Markham (1906), Tchaikovsky, Harvard University: G. Bell & sons

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, Singapore, Republic of Singapore: Leong Kit Meng, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Lidin, Olaf G. (2002), Tanegashima – The Arrival of Europe in Japan, Nordic Inst of Asian Studies, ISBN 8791114128

- Lorge, Peter A. (2008), The Asian Military Revolution: from Gunpowder to the Bomb, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-60954-8

- Lu, Gwei-Djen (1988), "The Oldest Representation of a Bombard", Technology and Culture, 29: 594–605

- Manigault, Edward; Warren Ripley (1996), Siege Train: The Journal of a Confederate Artilleryman in the Defense of Charleston, Charleston, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, ISBN 1-57003-127-4

- Manucy, Albert (1994), Artillery Through the Ages: A Short Illustrated History of Cannon, Emphasising Types Used in America, Diane Publishing, ISBN 0-7881-0745-3

- May, Timothy (2012), The Mongol Conquests in World History, Reaktion Books

- McCamley, Nicholas J. (2004), Disasters Underground, Pen & Sword Military, ISBN 1-84415-022-4

- McCarthy, Peter; Mike Syron (2003), Panzerkrieg: The Rise and Fall of Hitler's Tank Divisions, Carroll & Graf Publishers, ISBN 0-7867-1264-3

- McLahlan, Sean (2010), Medieval Handgonnes

- McNeill, William Hardy (1992), The Rise of the West: A History of the Human Community, University of Chicago Press .

- Morillo, Stephen (2008), War in World History: Society, Technology, and War from Ancient Times to the Present, Volume 1, To 1500, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-052584-9

- Needham, Joseph (1971), Science and Civilization in China Volume 4 Part 3, Cambridge At The University Press

- Needham, Joseph (1980), Science & Civilisation in China, 5 pt. 4, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08573-X

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-30358-3 .

- Nicolle, David (1990), The Mongol Warlords: Ghengis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane

- Nicolle, David (2000), Crécy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-85532-966-9

- Nolan, Cathal J. (2006), The Age of Wars of Religion, 1000–1650: an Encyclopedia of Global Warfare and Civilization, Vol 1, A-K, 1, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-33733-0

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300–1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press .

- Nossov, Konstantin (2007), Medieval Russian Fortresses AD 862–1480, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84603-093-2

- Nossov, Konstantin (2006), Russian Fortresses, 1480–1682, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-916-9

- Pacey, Arnold (1990), Technology in World Civilization: A Thousand-Year History, MIT Press, ISBN 0-262-66072-5

- Partington, J. R. (1960), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Cambridge, UK: W. Heffer & Sons .

- Partington, J. R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5954-9

- Patrick, John Merton (1961), Artillery and warfare during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, Utah State University Press .

- Pauly, Roger (2004), Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology, Greenwood Publishing Group .

- Perrin, Noel (1979), Giving up the Gun, Japan's reversion to the Sword, 1543–1879, Boston: David R. Godine, ISBN 0-87923-773-2

- Petzal, David E. (2014), The Total Gun Manual (Canadian edition), WeldonOwen .

- Phillips, Henry Prataps (2016), The History and Chronology of Gunpowder and Gunpowder Weapons (c.1000 to 1850), Notion Press

- Playfair, Ian S. O.; T. P. Gleave (1987), The Mediterranean and Middle East, HMSO, ISBN 0-11-630946-6

- Purton, Peter (2010), A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, Boydell Press, ISBN 1-84383-449-9

- Reymond, Arnold (1963), History of the Sciences in Greco-Roman Antiquity, Biblo & Tannen Publishers, ISBN 0-8196-0128-4

- Robins, Benjamin (1742), New Principles of Gunnery

- Rose, Susan (2002), Medieval Naval Warfare 1000-1500, Routledge

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Warfare in Pre-British India, Routledge

- Russ, Martin (1999), Breakout: The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, Korea 1950, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-029259-4

- Sadler, John (2006), Flodden 1513: Scotland's Greatest Defeat, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84176-959-2

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977a), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (2): 153–173 (153–157)

- Schmidtchen, Volker (1977b), "Riesengeschütze des 15. Jahrhunderts. Technische Höchstleistungen ihrer Zeit", Technikgeschichte 44 (3): 213–237 (226–228)

- Stone, George Cameron (1999), A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-40726-8

- Tran, Nhung Tuyet (2006), Viêt Nam Borderless Histories, University of Wisconsin Press .

- Tunis, Edwin (1999), Weapons: A Pictorial History, Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-6229-9

- Turnbull, Stephen (2003), Fighting Ships Far East (2: Japan and Korea Ad 612-1639, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-478-7

- Turnbull, Stephen (2004), The Walls of Constantinople AD 413–1453, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-759-X

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, III, New York: Pergamon Press .

- Villalon, L. J. Andrew (2008), The Hundred Years War (part II): Different Vistas, Brill Academic Pub, ISBN 978-90-04-16821-3

- Wagner, John A. (2006), The Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War, Westport & London: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0-313-32736-X

- Wallechinsky, David; Irving Wallace (1975), The People's Almanac, Doubleday, ISBN 0-385-04186-1

- Watson, Peter (2006), Ideas: A History of Thought and Invention, from Fire to Freud, Harper Perennial (2006), ISBN 0-06-093564-2

- Wilkinson, Philip (9 September 1997), Castles, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7894-2047-3

- Wilkinson-Latham, Robert (1975), Napoleon's Artillery, France: Osprey Publishing, ISBN 0-85045-247-3

- Willbanks, James H. (2004), Machine guns: an illustrated history of their impact, ABC-CLIO, Inc.

- Williams, Anthony G. (2000), Rapid Fire, Shrewsbury: Airlife Publishing Ltd., ISBN 1-84037-435-7

- Young, Mark C (2002), Guinness Book of World Records (2002 ed.), England: Bantam Books, ISBN 978-0-553-58378-6

- Zetterling, Niklas; Anders Frankson (2000), Kursk 1943: A Statistical Analysis, Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-5052-8

Further reading

- AAP-6 NATO Glossary of Terms and Definitions (PDF), North Atlantic Treaty Organization, 2007

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cannon. |

| Look up history of cannon in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Artillery Tactics and Combat during the Napoleonic Wars

- Handgonnes and Matchlocks – History of firearms to 1500

- U.S. Patent 5,236 – Patent for a Casting ordnance

- U.S. Patent 6,612 – Cannon patent

- U.S. Patent 13,851 – Muzzle loading ordnance patent