Battle of Crécy

The Battle of Crécy (26 August 1346), also spelled Cressy, was an English victory during the Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years' War. It was the first of three famous English successes during the conflict, followed by Poitiers in 1356 and Agincourt in 1415.

The battle was fought on 26 August 1346 near Crécy, in northern France. An army of English, Welsh, and allied mercenary troops led by Edward III of England, engaged and defeated a much larger army of French, Genoese and Majorcan troops led by Philip VI of France. Emboldened by the lessons of tactical flexibility and utilisation of terrain learned from the earlier Saxons, Vikings, Muslims and the recent battles with the Scots, the English army won an important victory.[6][7]

The battle heralded the rise of the longbow as the dominant weapon on the Western European battlefield, and helped to continue the rise of the infantryman in medieval warfare. Crécy also saw the use of the ribauldequin, an early cannon, by the English army. The heavy casualties taken by the French knightly class at the hands of peasants wielding ranged weapons was indicative of the decline of chivalry, and the emergence of a more practical, pragmatic approach to conducting warfare.[8]

The battle crippled the French army's ability to come to the aid of Calais, which fell to the English the following year. Calais would remain under English rule for over two centuries, falling in 1558.

Campaign background

On the death of Charles IV of France in 1328, Edward III of England was his closest male relative and legal successor. But a French court decreed that Charles' closest relative was his first cousin, Philip Count of Valois, who was crowned Philip VI of France. Reluctantly, Edward paid homage to Philip in his role as Duke of Aquitaine, a title he had inherited in 1329. Populated by Gascons with a culture and language separate from the French, the inhabitants of Aquitaine preferred a relationship with the English crown. However, France continued to interfere in the affairs of the Gascons, in matters both of law and war. Philip confiscated the lands of Aquitaine in 1337,[9] precipitating war between England and France. Edward declared himself King of France in 1340, and set about unseating his rival from the French throne.[10]

An early naval victory at Sluys in 1340 annihilated the French naval forces, giving the English domination at sea.[11]

Edward then invaded France with 12,000 men, cutting through the Low Countries plundering the countryside. After an aborted siege of Cambrai, Edward led his army on a destructive chevauchée through Picardy, destroying hundreds of villages, all the while shadowed by the French. Battle was given by neither side and Edward withdrew, bringing the campaign to an abrupt end.

Edward returned to England to raise more funds for another campaign and to deal with his political difficulties with the Scots, who were making repeated raids over the border.

On 11 July 1346, Edward set sail from Portsmouth with a fleet of 750 ships and an army of 15,000 men.[12] With the army were Edward's sixteen-year-old son, Edward, the Black Prince, a large contingent of Welsh soldiers, and allied knights and mercenaries from the Holy Roman Empire. The army landed at Saint-Vaast-la-Hougue, 20 miles from Cherbourg. The intention was to undertake a massive chevauchée across Normandy, plundering its wealth and severely weakening the prestige of the French crown. They razed Carentan, Saint-Lô and Torteval, then Edward turned his army against Caen, the ancestral capital of Normandy. The English army sacked Caen on 26 July, plundering the city's huge wealth. Moving off on 1 August, the army marched north to the River Seine, possibly intending to attack Paris. The English army crossed the Seine at Poissy;[13] however it was now between the Seine and the Somme rivers. Philip moved off with his army, attempting to entrap and destroy the English force.

Fording the Somme proved difficult: all bridges were either heavily guarded or burned. Edward vainly attempted the crossings at Hangest-sur-Somme and Pont-Remy before moving north. Despite some close encounters, the pursuing French army was unable to engage the English. Edward was informed of a tiny ford on the Somme, likely well defended, near the village of Saigneville, called Blanchetaque. On 24 August, Edward and his army successfully forced a crossing at Blanchetaque with few casualties. Such was the French confidence that Edward would not ford the Somme that the area beyond had not been denuded, allowing Edward's army to plunder it and resupply; Noyelles-sur-Mer and Le Crotoy were burned. Edward used the respite to prepare a defensive position at Crécy-en-Ponthieu while waiting for Philip to bring up his army.[14] The River Maye protected this position to the west, and the town of Wadicourt to the east, as well as a natural slope, which put cavalry at a disadvantage.

Battle

Preparation

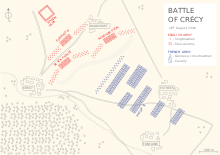

Edward deployed his army facing south on a sloping hillside at Crécy-en-Ponthieu; the slope put the French mounted knights at an immediate disadvantage. The left flank was anchored against Wadicourt, while the right was protected by Crécy itself and the River Maye beyond. This made it impossible for the French army to outflank them. The army was also well-fed and rested, giving them an advantage over the French, who did not rest before the battle.[15]

The English army

The English army was led by Edward III; it mainly comprised English and Welsh troops along with allied Breton, Flemish, and German mercenaries. The exact size and composition of the English force is not known. Andrew Ayton suggests a figure of around 2,500 men-at-arms: nobles and knights, heavily armoured and armed men, accompanied by their retinues. The army contained around 5,000 longbowmen, 3,000 hobelars (light cavalry and mounted archers) and 3,500 spearmen.[16] Clifford Rodgers suggests 2,500 men-at-arms, 7,000 longbowmen, 3,250 hobelars and 2,300 spearmen.[17] Jonathon Sumption believes the force was somewhat smaller, based on calculations of the carrying capacity of the transport fleet that was assembled to ferry the army to the continent. Based on this, he has put his estimate at around 7,000–10,000.[18]

The power of Edward's army at Crécy lay in the massed use of the longbow: a powerful tall bow made primarily of yew. Upon Edward's accession in 1327, he inherited a kingdom beset with two zones of conflict: Aquitaine and Scotland. England had not been a dominant military force in Europe: the French dominated in Aquitaine, and Scotland had all but achieved its independence since the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314. Previously, pitched battles in the medieval era had largely been decided by the massed charge of heavily armoured mounted knights, a widely feared force in their heyday. However, battles such as Manzikert had demonstrated their vulnerability to nimble mounted archers on fast horses, while engagements such as the Golden Spurs, Stirling, and Bannockburn, heralded the rise of the infantryman in effectively countering the armoured charge. Infantry did have significant advantages over heavily armoured cavalry; they were far cheaper to train and equip by comparison, and offered greater tactical flexibility, in that they could be deployed on almost any terrain.[19]

Longbows had been effectively used before by English armies. Edward I successfully used longbowmen to break up static Scottish schiltron formations at the Battle of Falkirk in 1298; however it was not until Edward III's reign that they were accorded greater significance in English military doctrine. Edward realised the importance of inflicting severe damage upon an enemy force before melée combat began; at Halidon Hill in 1333, he used massed longbowmen and favourable terrain to inflict a significant defeat on the Scots forces to very few casualties of his own—in some ways a harbinger of his similar tactics at Crécy. To ensure he had a force of experienced and equipped archers to call upon, Edward ingrained archery into English culture. He encouraged archery practice, and the production of stocks of arrows and bows in peacetime, as well as war. In 1341, when Edward led an expedition to Brittany, he ordered the gathering of 130,000 sheaves, a total of 2.6 million arrows; an impressive feat on such short notice.[20]

A common claim for the longbow was its ability to penetrate plate armour due to its draw weight, a claim contested by contemporary accounts and modern tests. A controlled test conducted by Mike Loades at the Royal Military College of Science's ballistics test site for the programme Weapons That Made Britain – The Longbow found that arrows shot at a speed of around 52 metres per second against a plate of munition-quality steel (not specially hardened) were ineffective at a range of around 80 metres, enough to mildly bruise/wound the target at 30 metres, and lethal at a range of 20 metres.[21] Archery was described as ineffective against plate armour by contemporaries at battles such as Bergerac in 1345, Neville's Cross in 1346 and Poitiers in 1356. Later studies also found that late period plate armour such as that employed by Italian city-state mercenary companies was effective at stopping contemporary arrows.[22][23] Horses, however, were almost wholly unprotected against arrows, and arrows could penetrate the lighter armour on limbs. Clifford Rodgers, commenting on the later, similar Battle of Agincourt, argues that the psychological effect of a massive storm of arrows would have broken the fighting spirit of the target forces.

Archers were issued with around 60–72 arrows before a battle began. Most archers would not shoot at the maximum rate, around six per minute for the heaviest bows,[24] as the psychological and physical exertion of battle strained the men. As the battle wore on, the arm and shoulder muscles would tire from exertion, the fingers holding the bowstring would strain and the stress of combat would slacken the rate of fire.[25]

The English army was also equipped with five ribauldequin, an early form of cannon.[26]

The French army

The French army was led by Philip VI and the blind John of Bohemia. The exact size of the French army is less certain as the financial records from the Crécy campaign are lost, however there is a prevailing consensus that it was substantially larger than the English. The French army likely numbered around 20,000–30,000 men. Contemporary chronicler Jean Froissart places the French numbers at 100,000, Wynkeley suggests 12,000 men-at-arms, 6,000 Genoese Crossbowmen and 60,000 infantry, and Henry Knighton claimed the king of France brought 72,000.[27] Jean Le Bel gave 20,000 cavalry, 100,000 foot and 12,000 crossbowmen. Thomas of Burton reported 30,000 cavalry. An Italian chronicler claimed 100,000 knights, 12,000 infantry and 5,000 crossbowmen.[28] Contemporary chroniclers estimated the number of crossbowmen as 2,000–20,000.[29]

These numbers have been described as unrealistic and exaggerated by historians, going by the extant war treasury records for 1340, six years before the battle.[30] Ayton suggests around 12,000 mounted men-at-arms as the core soldiery of the French army, several thousand Genoese crossbowmen and a "large, though indeterminate number of common infantry".[2] Most historians have accepted the figure of 6,000 Genoese crossbowmen.[31] Schnerb questions this figure, however, based on the estimates of 2,000 available crossbowmen in all of France in 1340. That Genoa on its own could have put several thousand mercenary crossbowmen at the disposal of the French monarch is described by Schnerb as "doubtful".[32] The contingent of common infantrymen is not known with any certainty, except that it outnumbered the English and was in the thousands.[33]

Longbow versus crossbow

The Battle of Crécy is often exemplified as a battle in which the longbow defeated the rival crossbow. The crossbow had become the dominant ranged infantry weapon on the continental European battlefield: the choice weapon for expert mercenary companies. The crossbow was favoured as it required less physical strength to load and shoot than a longbow, and could release more kinetic energy than its rival, making it deadlier at close range. It was, however, hampered by slower, more difficult loading, its cumbersome shape and its range, in which the longbow had the advantage. Furthermore a sudden rainstorm is said to have stretched the strings of the crossbows while the English longbowmen had removed their bowstrings, and stored them under their water-resistant leather caps.

Later developments in more powerful crossbows in the 15th century, such as the windlass-span crossbow, negated these advantages, while advances in bow technology brought to Europe from armies on crusade introduced composite technology; decreasing the size of the crossbow while increasing its power. A common claim about the crossbow is a reload time of one bolt every 1–2 minutes. A test conducted by Mike Loades for Weapons That Changed Britain – The Longbow found that a belt-and-claw span crossbow could discharge 4 bolts in 30 seconds, while a longbow could shoot 9.[21] A second speed test conducted using a hand-span crossbow found that the weapon could shoot 6 bolts in the same time it took for a longbow to shoot 10.[34]

Initial deployments

The English army was deployed in three divisions, or "battles". Edward's son, Edward, the Prince of Wales commanded the vanguard with John de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, Thomas de Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick and Sir John Chandos. This division lay forward from the rest of the army and would bear the brunt of the French assault. Edward himself commanded the division behind, while the rear division was led by William de Bohun, Earl of Northampton. Each division was composed of spearmen in the rear, men-at-arms in the centre and the longbowmen arrayed in front of the army in a jagged line.[35][36] The exact location of the English baggage train is not known. Edward ordered his men-at-arms to fight on foot rather than stay mounted.[37] The English also dug a series of ditches, pits and caltrops to maim the French cavalry.

The French army came north from Abbeyville, the advance guard arriving at the Crécy ridgeline at around midday on 26 August. After reconnoitering the English position, it was advised to Philip that the army should encamp and give battle the following day. Philip met stiff resistance from his senior nobles, but decided that the attack would be made that day. This put them at a significant disadvantage; the English army was well-fed after plundering the countryside and well-rested, having slept in their positions the night before the battle.[15] The French were further hampered by the absence of their Constable. It was the duty of the Constable of France to lead its armies in battle, however, the Constable Raoul II of Brienne, Count of Eu had been taken prisoner when the English army sacked Caen, depriving them of his leadership. Philip formed up his army for battle; the Genoese under Antonio Doria and Carlo Grimaldi formed the vanguard, followed by a division of knights and men-at-arms led by Charles II, Count of Alençon accompanied by the blind King John of Bohemia. The next division was led by Rudolph, Duke of Lorraine and Louis II, Count of Blois, while Philip himself commanded the rearguard.[36]

The French attack

The French army moved forward late in the afternoon, around 4pm after it had formed up. As it advanced, a sudden rainstorm broke over the field of battle. The English archers de-strung their bows to avoid the strings becoming slackened; the Genoese with their crossbows could take no such precautions, resulting in damage to their weapons.[38] The crossbowmen began their advance; however, they had left their pavises back in the baggage train, and thus had no means of protection as they loaded their weapons.[39][40] The Genoese moved within range and discharged their crossbows. Damaged by the rain, their efforts had little effect on the English line. The English archers shot their bows in retaliation, inflicting heavy casualties on the Genoese, causing them to retreat. The knights and nobles following in Alençon's division, seeing the routed mercenaries, hacked them down as they retreated. Froissart writes of the event:

The English, who were drawn up in three divisions and seated on the ground, on seeing their enemies advance, arose boldly and fell into their ranks... You must know that these kings, earls, barons, and lords of France did not advance in any regular order... There were about fifteen thousand Genoese crossbowmen; but they were quite fatigued, having marched on foot that day six leagues, completely armed, and with their wet crossbows. They told the constable that they were not in a fit condition to do any great things that day in battle. The Count of Alençon, hearing this, was reported to say, "This is what one gets by employing such scoundrels, who fail when there is any need for them."[41]

— Chateaubriand, after Froissart's middle French, gives: "On se doit bien charger de telle ribaudaille qui faille au besoin"[42]

The clash of the retreating Genoese and the advancing French cavalry threw the army into disarray. The longbowmen continued to discharge their bows into the massed troops, while five ribauldequin, early cannon, added to the confusion, though it is doubtful that they had inflicted any significant casualties.[43] Froissart writes that such guns fired "two or three discharges on the Genoese", likely large arrows or primitive grapeshot. Giovanni Villani writes of the guns:

The English guns cast iron balls by means of fire...They made a noise like thunder and caused much loss in men and horses... The Genoese were continually hit by the archers and the gunners... [by the end of the battle], the whole plain was covered by men struck down by arrows and cannon balls.[44]

With the Genoese defeated, the French cavalry mounted a charge upon the English ranks. However, the slope and obstacles laid by the English disrupted the attack. Successive charges had to be made through ever-increasing numbers of dead and wounded, hampering their subsequent effectiveness. Despite the repeated attacks, the French cavalry could not break the English position. The Black Prince's division was particularly hard-pressed during the fighting. When reinforcements were requested from Edward, the king famously said; "I am confident he will repel the enemy without my help. Let the boy win his spurs". During the fighting along the Black Prince's division, the blind king John of Bohemia was struck down and killed.

The assault continued well into the night, with the French nobility stubbornly refusing to yield. Finally, Philip abandoned the field of battle. The French king had two horses killed from underneath him, and had taken an arrow to the jaw. His sacred and royal banner, the Oriflamme, was captured and taken, one of the five occasions this occurred during the banner's century-long history.[45] The battle ended soon after Philip withdrew, with the majority of the French army melting away from the field. The following day, after the morning fog had lifted, 2,000 longbowmen, supported by 500 spearmen, advanced down the slope and drove away the French levies who had remained.[46]

Aftermath

Casualties

The losses in the battle were highly asymmetrical. All contemporary sources give very low casualty figures for the English.[47] Geoffrey the Baker gives around 300 English soldiers killed at a highest estimate.[5] While some consider the low English casualty figures to be improbably low, Rogers argues that they are consistent with reports of casualties on the winning side in other medieval battles. Most casualties in medieval battles were incurred during the retreat, often resulting in heavily lopsided victories. Thus far, only two Englishmen killed at the battle have been identified: the squire Robert Brente and the newly anointed knight Aymer Rokesley.[48] Two English knights were also taken prisoner, although it is unclear at what stage in the battle this happened.[5]

Contemporary sources provide casualty figures for the French that are generally considered to be highly exaggerated. An estimate by Geoffrey le Baker deemed credible by Michael Prestwich states that 4,000 French knights were killed.[49] According to a body count made after the battle, 1,542 French knights and squires were found in front of the lines commanded by the Black Prince, Sumption assumes another "few hundred" men-at-arms were killed in the pursuit which followed.[50] Ayton estimates at least 2,000 French men-at-arms were killed, noting that over 2,200 heraldic coats were taken from the field of battle as war booty by the English.[51]

According to Ayton, the heavy losses of the French can also be attributed to the chivalric ideals held by knights at the time; nobles would have preferred to die in battle, or be captured and then accorded for ransom, rather than dishonourably flee the field.[52] Although considered to be heavy, no reliable figures exist for losses among the common French soldiery. Jean le Bel estimated 1,200 dead knights and 15,000–16,000 others.[53] Froissart writes that the French army suffered a total of 30,000 killed or captured, though these numbers are likely exaggerated.[54] Several secondary sources place an estimate on 12,000 killed or wounded, though it should be noted this number is not substantively reinforced by academics.[55][56][57]

Campaign and legacy

The battle crippled the French army's ability to come to the aid of Calais, which was besieged by Edward's army the following month. Calais fell after a year-long siege and would become an exclave of England, remaining under English rule until 1558.

In subsequent engagements, French men-at-arms would dismount to assail English longbowmen rather than stay mounted, as was advised to John II at Poitiers. The majority of the French soldiery at Agincourt also fought dismounted. Despite this, the French suffered similarly catastrophic defeats at those engagements as they did at Crécy.

The revolution in tactics heralded the rise of the longbow as the dominant weapon in Western Europe, and signalled a dramatic shift away from the focus of prior medieval battles; that of the mounted knight. The slaughter of the French nobility at the hands of longbowmen, who were commoners and peasants in English society, caused a huge shock in France, as infantrymen began to play a greater role in medieval warfare. Though the Hundred Years' War would feature clashes that have been since held as the model of chivalry, such as the Combat of the Thirty, the combined-arms approach of the English at Crécy saw the emergence of a more practical, pragmatic approach to conducting warfare; one where tactics and achieving victory held greater importance than observing chivalric codes of knightly conduct.[8] The battle helped to contribute to the infantry revolution, where innovations and shifts in military thinking began to erode the importance of the heavily armoured mounted knight.

After the equally disastrous French defeat at Poitiers, the Edwardian phase of the Hundred Years' War would draw to a close, with very favourable terms for the English.

Renaissance Florence

To finance the army for the campaign, Edward III had relied on loans from Florentine bankers, in particular the three largest banks in Florence (and Europe) at the time—the banks of the families of Bardi, Peruzzi, and Acciaiuoli. Despite being victorious, Edward III largely defaulted on England's debt which led to the bankruptcy and destruction of all three banking houses.[58] Their closure enabled the rise of the house of Medici, later founded by Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, which would define early modern European banking, create modern accounting, and finance many of the greatest artists of the Renaissance along with Galileo.

Nobles and men at arms at the battle

The young Prince of Wales had with him:

- Thomas de Beauchamp, 11th Earl of Warwick

- John de Vere, 7th Earl of Oxford

- Sir Godfrey de Harcourt

- Reginald de Cobham, 1st Baron Cobham

- Thomas Holland, 1st Earl of Kent

- Ralph de Stafford, 1st Earl of Stafford

- Lord Mauley

- Lord de la Warre

- Sir John Chandos

- Bartholomew de Burghersh, 2nd Baron Burghersh

- Lord Robert Neville

- Lord Thomas Clifford

- Robert Bourchier, 1st Baron Bourchier

- William Latimer, 4th Baron Latimer

- Richard FitzAlan, 10th Earl of Arundel

- William de Ros, 3rd Baron de Ros

- Willoughby, Basset, St Albans, Sir Lewis Tufton, Lord Multon and the Lord Lascels.[37]

- Sir Thomas Felton, a member of the Order of the Garter, fought at Crécy and Poitiers.[59][60]

Others included:

- Sir Richard Fitz-Simon

- Sir Miles Stapleton of Bedale

- William de Bohun, 1st Earl of Northampton

- John le Strange, 2nd Baron Strange of Blackmere

- Earl Bowden

- Sir John Sully

- Sir John Giffard of Twyford

- Sir Richard Pembrugge (Pembroke).[61]

In front of the French army were the Moisne of Basle, the Monk of Bazeilles, the lords of Beaujen and Noyles and Louis of Spain. The French army was led by Phillip VI; surrounding him were:

- Charles II, Count of Alençon

- Louis I, Count of Flanders

- Louis II, Count of Blois

- Rudolph, Duke of Lorraine

- Jean de Hainaut and de Montmorency, and a gathering of the lords.

Moisne of Basle related the location and formation of the English forces.[62] Charles, king of the Romans, son of John of Bohemia, was also present and lightly wounded in the battle.

Fictional accounts

A fictional portrayal of the Battle of Crécy is included in the Ken Follett novel World Without End. The book describes the battle from an English knight's perspective, that of an archer, and from that of a neutral observer. This novel was made into a telefilm in 2012 and the Battle of Crécy is included, albeit in a very summarized form.

Another depiction can be found in Warren Ellis' & Raulo Caceres' graphic novel Crécy, which frames the battle as a narration by a Suffolk archer; or in Bernard Cornwell's fictional account of an archer in the Hundred Years' War, Harlequin (UK title), part of the Grail Quest novel series, or The Archer's Tale (US title). The lead character Thomas of Hookton, is an English archer who fights in the battle.

The battle appears in "The campaign of 1346, as an historical drama" by Christopher Godmond.

It is also portrayed in Ronald Welch's Bowman of Crécy and in David Gilman's Master of War.

The protagonist, Edmund Beche, in P.C. Doherty's The Death of a King (1985) is present at the battle and describes it from the perspective of a bowman on the right flank near the village of Crécy.

In G. A. Henty's historical fiction book, St. George for England the main character is present at the battles of Cressy and Poitiers.[63]

The battle is a crucial episode in the life of the hero Hugh de Cressi (his name is apparently a coincidence), in the H. Rider Haggard novel "Red Eve". The battle is described in some detail, including, for example the failure of the Genoese bowmen, attributed in the book, as above, to wet strings; and also the merciless treatment of the French wounded.[64]

In Michael Jecks 2014 book Fields of Glory, the entire campaign is viewed from the point of view of a vintaine of archers under the command of the non fictional Sir John de Sully commencing with the landing in Normandy and terminating with a detailed description of the eventual final battle at Crecy.[65] It highlights the devastating effects of the chevauchée as the English laid waste to the countryside in an attempt to bring the French army into the field to protect its inhabitants.

The battle features at the climax of another 2014 novel, Son of the Morning, by Mark Barrowcliffe writing as Mark Alder. A fantasy take on the Hundred Years' War, the novel depicts English and French forces as being supported by devils and angels.[66]

The battle is referred to several times - though never seen directly - in Michael Crichton's 1999 science-fiction novel Timeline, in which a group of archaeologists are transported back in time to fourteenth-century France. Crichton gives credit to the English for winning the battle in the face of vastly superior forces, citing the English willingness to adopt a less ceremonial style of battle and instead using what he calls "shock troops" - mercenary archers who were paid a wage for their services, trained on a daily basis much like modern soldiers, and were deadly accurate in their ability to make enemy kills from a distance of what would today be the equivalent of two or more football fields, something that would have been impossible for the French chevaliers with their short-range style of fighting.

See also

- Medieval warfare

- Battle of Agincourt in 1415 for a similar battle won by English/Welsh longbowmen

- Battle of Poitiers (1356)

References

- ↑ Ayton, "The English Army at Crécy" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 189; Rogers (2000), p. 423

- 1 2 Ayton, "The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 18

- ↑ Schnerb, "The French Army before and after 1346" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 269

- ↑ Sumption (1990), p. 526

- 1 2 3 Ayton, "The English Army at Crécy", in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 191

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) Introduction p. 8

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) pp. 8, 12

- 1 2 Santosuosso 2004, pp. 130–36

- ↑ Inscribing the Hundred Years' War in French and English Cultures, ed. Denise Nowakowski Baker, (State University of New York Press, 2000), 4.

- ↑ Anthony Goodman, John of Gaunt: The Exercise of Princely Power in Fourteenth-Century Europe, (Routledge, 2013), 28.

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 10

- ↑ Prestwich. Plantagenet England. p. 315

- ↑ Rothero (2005), pp. 4–6

- ↑ Curry (2002), pp. 31–39.

- 1 2 Rothero (2005), pp. 2–6

- ↑ Ayton, "The English Army at Crécy" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 189; Rogers (2000), p. 423

- ↑ Rogers (2000), p. 423

- ↑ Sumption (1990) p. 497

- ↑ Nicholson (2004), p. 14

- ↑ "Battle of Crécy". 20 August 2009.

- 1 2 Midieval Weapons and Combat – The Longbow (Middle Ages Battle History Documentary). 11 May 2014 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Strickland & Hardy 2005, pp. 272–278

- ↑ Kaiser 2003

- ↑ Strickland & Hardy 2005, p. 31

- ↑ Barker 2006

- ↑ Ayton & Preston (2005

- ↑ Geoffrey (eds. & trans.), Martin (1995). Knighton's Chronicle, 1337–1396. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-19-820 503-1.

- ↑ DeVries 2015, p. 314.

- ↑ Devries (1996), p. 164

- ↑ Schnerb, "The French Army before and after 1346" in Ayton & Preston (2005), p. 269

- ↑ Lynn (2003), p. 74; Sumption (1990), p. 526

- ↑ Schnerb, "The French Army before and after 1346" in Ayton & Preston (2005), pp. 268–69

- ↑ Curry (2002), p. 40; Lynn (2003), p. 74

- ↑ The Longbow Vs The Crossbow Speed Test – Video 17. 11 April 2009 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Rothero (2005), pp. 5–6

- 1 2 Neillands, Robin (2001). The Hundred Years War. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415261319.

- 1 2 Chronicles of England, France and Spain and the Surrounding Countries, by Sir John Froissart, Translated from the French Editions with Variations and Additions from Many Celebrated MSS, by Thomas Johnes, Esq; London: William Smith, 1848. pp. 160–171.

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) pp. 49, 50

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 66

- ↑ Jean Birdsall edited by Richard A. Newhall. The Chronicles of Jean de Venette (N.Y. Columbia University Press. 1953) p.43

- ↑ Amt (2001), p. 330.

- ↑ Chateaubriand, 'Invasion de la France par Edouard', in Volume 7 from the complete works of 1834; p.37.

- ↑ Ayton & Preston (2005)

- ↑ Nicolle (2000)

- ↑ Osprey Publishing (2000) Crécy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow, Osprey Publishing. p72

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) pp. 76–77

- ↑ Prestwich (1996), p. 331; Rogers (2008), p. 215; Sumption (1990), p. 530

- ↑ Rogers (2007), p. 215

- ↑ Prestwich (1996), p. 331

- ↑ Sumption (1990), p. 530

- ↑ Ayton, "The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance" in Ayton & Preston (2005), pp. 19–20

- ↑ Ayton, "The Battle of Crécy: Context and Significance" in Ayton & Preston (2005), pp. 25–26

- ↑ Devries (1996), p. 174

- ↑ Froissart, Jean. The Chronicles of Froissart, John Bourcher [Lord Berners], tr., G.C. Macaulay, ed. (London : Macmillan, 1908), pp. 99–107

- ↑ "Battle of Crecy - Aug 26, 1346 - HISTORY.com".

- ↑ "Crecy". www.longbow-archers.com.

- ↑ "Hundred Years' War: Battle of Crécy".

- ↑ De Roover, Raymond The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank: 1397–1494. Beard Books, Washington, D.C.; 1999. Introduction p.2

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography p308 col. 2

- ↑ 67 (app c.1381) List of Members of the Order of the Garter

- ↑ The chronicles of Froissart. Translated by John Bourchier, Lord Berners. Edited and reduced into one volume by G. C. Macauly former fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. (Macmillan & Co., Ltd 1904 not in copyright) Chpt. CXXX pps. 104–106

- ↑ Henri de Wailly. Introduction by Emmanuel Bourassin, Crecy 1346: Anatomy of a Battle (Blandford Press, Poole, Dorset 1987) p. 58

- ↑ "Saint George for England".

- ↑ "Red Eve". Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ "Fields of Glory – Kindle edition by Michael Jecks. Literature & Fiction Kindle eBooks @ Amazon.com".

- ↑ Orion Books publisher page for Son of the Morning

Bibliography

- Ayton, Andrew; Preston, Philip; et al. (2005). The Battle of Crecy, 1346. Boydell Press.

- Amt, Emilie, ed. (2001). Medieval England 1000–1500: A Reader. Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press. ISBN 1-55111-244-2.

- Barber, Richard W. Edward III and the Triumph of England: The Battle of Crécy and the Company of the Garter. London: Allen Lane, 2013. ISBN 9780713998382 OCLC 839314940

- Curry, Anne, Essential Histories: The Hundred Years' War 1337–1453. Osprey Publishing, Oxford; 2002. ISBN 1841762695 OCLC 59427611

- De Roover, Raymond The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank: 1397–1494. Beard Books, Washington, D.C.; 1999. ISBN 1893122328

- DeVries, Kelly. Infantry Warfare in the Early Fourteenth Century. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 1996. ISBN 0851155677 OCLC 34356019

- DeVries, Kelly (2015). "The Implications of the Anomino Romano Account of the Battle of Crécy". In Halfond, Gregory. The Medieval Way of War: Studies in Medieval Military History in Honor of Bernard S. Bachrach (1st ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1472419583.

- Lansing & English A Companion to the Medieval World. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford; (editors 2009). ISBN 9781405109222 OCLC 276930478

- Lynn, John A. (2003), Battle: A History of Combat and Culture. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. ISBN 0813333725 OCLC 58548315

- Matthews, Rupert. The Battle of Crecy. Stroud: Spellmount, 2007. ISBN 9781862273696 OCLC 78989699

- Nicolle, David (2000). Crécy 1346: Triumph of the longbow. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-85532-966-2.

- Rogers, Clifford. War Cruel and Sharp: English Strategy under Edward III, 1327–1360, Chapter 11. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2000. ISBN 0851158048 OCLC 44420496

- Rogers, Clifford J, Soldiers' Lives through History: The Middle Ages. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2007. ISBN 9780313333507 OCLC 464726482

- Rothero, Christopher The Armies of Crecy and Poitiers. Osprey Publishing, Oxford; 2005. ISBN 0850453933 OCLC 8698451

- Sumption, Jonathan. The Hundred Years War, Volume I: Trial by Battle. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990. ISBN 0812216555 OCLC 46838615

Primary sources

- The Anonimalle Chronicle, 1333–1381. Edited by V.H. Galbraith. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1927.

- Avesbury, Robert of. De gestis mirabilibus regis Edwardi Tertii. Edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. London: Rolls Series, 1889.

- Chronique de Jean le Bel. Edited by Eugene Deprez and Jules Viard. Paris: Honore Champion, 1977.

- Dene, William of. Historia Roffensis. British Library, London.

- French Chronicle of London. Edited by G.J. Aungier. Camden Series XXVIII, 1844.

- Froissart, Jean. Chronicles. Edited and Translated by Geoffrey Brereton. London: Penguin Books, 1978.

- Grandes chroniques de France. Edited by Jules Viard. Paris: Société de l'histoire de France, 1920–53.

- Gray, Sir Thomas. Scalacronica. Edited and Translated by Sir Herbert Maxwell. Edinburgh: Maclehose, 1907.

- Le Baker, Geoffrey. Chronicles in English Historical Documents. Edited by David C Douglas. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969.

- Le Bel, Jean. Chronique de Jean le Bel. Edited by Jules Viard and Eugène Déprez. Paris: Société de l'historie de France, 1904.

- Rotuli Parliamentorum. Edited by J. Strachey et al., 6 vols. London: 1767–83.

- St. Omers Chronicle. Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, MS 693, fos. 248-279v. (Currently being edited and translated into English by Clifford J. Rogers)

- Venette, Jean. The Chronicle of Jean de Venette. Edited and Translated by Jean Birdsall. New York: Columbia University Press, 1953.

Anthologies of translated sources

- Life and Campaigns of the Black Prince. Edited and Translated by Richard Barber. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1997.

- The Wars of Edward III: Sources and Interpretations. Edited and Translated by Clifford J. Rogers. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 1999.

Further reading

- Barber, Richard. Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine: A Biography of the Black Prince. Scribner, 1978. ISBN 0684158647 OCLC 4360312

- Belloc, Hilaire Crécy. Covent Garden, London: Stephen Swift and Co., LTD. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/32196, 1912.

- Burne, Alfred H. The Crecy War: A Military History of the Hundred Years War from 1337 to the peace of Bretigny, 1360. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1955. ISBN 7400020129 OCLC 962690

- Fowler, Kenneth (editor), The Hundred Years War. Suffolk, UK: Richard Clay. The Chaucer Press, 1971.

- Hewitt, H.J. The Organization of War under Edward III. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1966. OCLC 398232

- Keen, Maurice (editor), Medieval Warfare: A History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0198206399 OCLC 41581804

- Livingston, Michael, and Kelly DeVries, eds. The Battle of Crécy: A Casebook (2016). ISBN 9781781382646

- Nicolle, David, Crecy 1346: Triumph of the Longbow. (Osprey, 2000). ISBN 978-1-85532-966-9

- Ormrod, W.D. The Reign of Edward III. Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing, Inc, 2000.

- Packe, Michael. King Edward III. (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1985).

- Prestwich, Michael. Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages: The English Experience. (Yale UP, 1996).

- Prestwich, Michael. The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377. (St. Martin's Press, 1980).

- Reid, Peter. A Brief History of Medieval Warfare: The Rise and Fall of English Supremacy at Arms, 1314–1485. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2007.

- Rogers, Clifford J. Essay on Medieval Military History: Strategy, Military Revolution, and the Hundred Years War. Surrey, UK: Ashgate Variorum, 2010. ISBN 9780754659969 OCLC 461272357

- Seward, Desmond. The Hundred Years War: The English in France 1337–1453. London, UK: Constable and Company Ltd, 1996.

- Tuchman, Barbara. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Random House, 1987 ISBN 0345349571

- Waugh, Scott L. England in the reign of Edward III. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

External links

- Crecy 1346 by Jeffery P. Berry

- "An animated map of the Battle of Crecy" by David Crowther

- "An animated map of the Crecy campaign" by David Crowther