List of inventions in the medieval Islamic world

The following is a list of inventions made in the medieval Islamic world, especially during the "Islamic Golden Age" (8th to 13th centuries),[1][2] as well as the late medieval period, especially in the Emirate of Granada and the Ottoman Empire.

Science and technology in the Islamic world adopted and preserved knowledge and technologies from contemporary and earlier civilizations, including Persia, India, China, and Greco-Roman antiquity, while making a number of improvements and innovations.

List of inventions

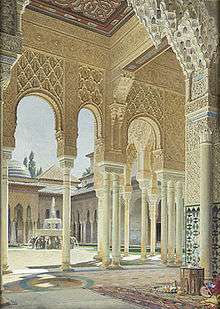

The interiors of the Alhambra in Spain are decorated with arabesque designs.

Al-Kindi's 9th-century Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages was the first book on cryptanalysis and frequency analysis.

Arab caliphates

- 8th century

- Tin-glazing: The tin-glazing of ceramics was invented by Muslim potters in 8th-century Basra, Iraq.[3] The oldest fragments found to-date were excavated from the palace of Samarra about 80 kilometres (50 miles) north of Baghdad.[4]

- 9th century

- Lusterware: Lustre glazes were applied to pottery in Mesopotamia in the 9th century; the technique soon became popular in Persia and Syria.[5] Earlier uses of lustre are known.

- Frequency analysis in cryptology: the first known recorded explanation of cryptanalysis was given by Al-Kindi (also known as "Alkindus" in Europe), in A Manuscript on Deciphering Cryptographic Messages. This treatise includes the first description of the method of frequency analysis.[6][7]

- Mental institute: In 872, Ahmad ibn Tulun built a hospital in Cairo that provided care to the insane, which included music therapy.[8]

- 10th century

- Vertical-axle windmill: A small wind wheel operating an organ is described as early as the 1st century AD by Hero of Alexandria.[9][10] The first vertical-axle windmills were eventually built in Sistan, Persia as described by Muslim geographers. These windmills had long vertical driveshafts with rectangle shaped blades.[11] They may have been constructed as early as the time of the second Rashidun caliph Umar (634-644 AD), though some argue that this account may have been a 10th-century amendment.[12] Made of six to twelve sails covered in reed matting or cloth material, these windmills were used to grind grains and draw up water, and used in the gristmilling and sugarcane industries.[13] Horizontal axle windmills of the type generally used today, however, were developed in Northwestern Europe in the 1180s.[9][10]

- Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī (973-1048) believed that light has a finite speed, and he was the first to discover that the speed of light is much faster than the speed of sound [14] [15].

- 11th century

- Mercuric chloride (formerly corrosive sublimate): used to disinfect wounds. [16]

- 12th century

- Bridge mill: The bridge mill was a unique type of watermill that was built as part of the superstructure of a bridge. The earliest record of a bridge mill is from Córdoba, Spain in the 12th century.[17]

- Hybrid trebuchet: The term Al-Ghadban (The Furious One) was applied to the hybrid trebuchet, though the usage of the term was not consistent and may have taken on a broader meaning.[18] The first record of a counterweight trebuchet was in the 12th century from Mardi ibn Ali al-Tarsusi while talking of the conquests of Saladin.[19]

- 13th century

- Fritware: It refers to a type of pottery which was first developed in the Near East, beginning in the late 1st millennium, for which frit was a significant ingredient. A recipe for "fritware" dating to c. 1300 AD written by Abu’l Qasim reports that the ratio of quartz to "frit-glass" to white clay is 10:1:1.[20] This type of pottery has also been referred to as "stonepaste" and "faience" among other names.[21] A 9th-century corpus of "proto-stonepaste" from Baghdad has "relict glass fragments" in its fabric.[22]

Emirate of Granada

- 14th century

- Hispano-Moresque ware: This was a style of Islamic pottery created in Arab Spain, after the Moors had introduced two ceramic techniques to Europe: glazing with an opaque white tin-glaze, and painting in metallic lusters. Hispano-Moresque ware was distinguished from the pottery of Christendom by the Islamic character of its decoration.[23]

Ottoman Empire

- 15th century

- Coffee: Stories exist of coffee originating in Ethiopia, but the earliest credible evidence of either coffee drinking or knowledge of the coffee tree appears in the middle of the 15th century, in the Sufi monasteries of the Yemen in southern Arabia.[24][25] It was in Yemen that coffee beans were first roasted and brewed as they are today. From Mocha, coffee spread to Egypt and North Africa,[26] and by the 16th century, it had reached the rest of the Middle East, Persia and Turkey. From the Muslim world, coffee drinking spread to Italy, then to the rest of Europe, and coffee plants were transported by the Dutch to the East Indies and to the Americas.[27]

- Iznik pottery: Produced in Ottoman Turkey as early as the 15th century AD.[28] It consists of a body, slip, and glaze, where the body and glaze are "quartz-frit."[29] The "frits" in both cases "are unusual in that they contain lead oxide as well as soda"; the lead oxide would help reduce the thermal expansion coefficient of the ceramic.[30] Microscopic analysis reveals that the material that has been labeled "frit" is "interstitial glass" which serves to connect the quartz particles.[31]

- 16th century

- Hookah or waterpipe: according to Cyril Elgood (PP.41, 110), the physician Irfan Shaikh, at the court of the Mughal emperor Akbar I (1542–1605) invented the Hookah or waterpipe used most commonly for smoking tobacco.[32][33][34][35]

- Marching band and military band: The marching band and military band both have their origins in the Ottoman military band, performed by the Janissary since the 16th century.[36]

See also

- Islamic Golden Age

- Timeline of science and engineering in the Islamic world

- Science in medieval Islam

- Science in the medieval Islamic world

- Islamic attitudes towards science

- Medicine in the medieval Islamic world

- Islamic arts

- Islamic economics

- Islamic literature

- Islamic philosophy

- Islamic technology

- Gunpowder Empires

Notes

- ↑ p. 45, Islamic & European expansion: the forging of a global order, Michael Adas, ed., Temple University Press, 1993, ISBN 1-56639-068-0.

- ↑ Max Weber & Islam, Toby E. Huff and Wolfgang Schluchter, eds., Transaction Publishers, 1999, ISBN 1-56000-400-2, p. 53

- ↑ Mason, Robert B. (1995), "New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World", Muqarnas: Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, Brill Academic Publishers, XII: 1, doi:10.2307/1523219, ISBN 90-04-10314-7.

- ↑ Caiger-Smith, 1973, p.23

- ↑ Ten thousand years of pottery, Emmanuel Cooper, University of Pennsylvania Press, 4th ed., 2000, ISBN 0-8122-3554-1, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Broemeling, Lyle D. (1 November 2011). "An Account of Early Statistical Inference in Arab Cryptology". The American Statistician. 65 (4): 255–257. doi:10.1198/tas.2011.10191.

- ↑ Al-Kadi, Ibrahim A. (1992). "The origins of cryptology: The Arab contributions". Cryptologia. 16 (2): 97–126. doi:10.1080/0161-119291866801.

- ↑ Koenig, Harold George (2005). Faith and mental health: religious resources for healing. Templeton Foundation Press. ISBN 1-932031-91-X.

- 1 2 Drachmann, A.G. (1961), "Heron's Windmill", Centaurus, 7: 145–151, doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1960.tb00263.x.

- 1 2 Dietrich Lohrmann, "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte, Vol. 77, Issue 1 (1995), pp.1-30 (10f.)

- ↑ Ahmad Y Hassan, Donald Routledge Hill (1986). Islamic Technology: An illustrated history, p. 54. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-42239-6.

- ↑ Dietrich Lohrmann (1995). "Von der östlichen zur westlichen Windmühle", Archiv für Kulturgeschichte 77 (1), p. 1-30 (8).

- ↑ Donald Routledge Hill, "Mechanical Engineering in the Medieval Near East", Scientific American, May 1991, pp. 64-9 (cf. Donald Routledge Hill, Mechanical Engineering Archived 25 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine.)

- ↑ https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1312/1312.7288.pdf

- ↑ http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/history/Biographies/Al-Biruni.html

- ↑ Maillard, Adam P. Fraise, Peter A. Lambert, Jean-Yves (2007). Principles and Practice of Disinfection, Preservation and Sterilization. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 0470755067.

- ↑ Lucas, Adam (2006), Wind, Water, Work: Ancient and Medieval Milling Technology, Brill Publishers, pp. 62 & 64, ISBN 90-04-14649-0

- ↑ Chevedden, Paul E. (1 January 2000). "The Invention of the Counterweight Trebuchet: A Study in Cultural Diffusion". Dumbarton Oaks Papers. 54: 71. doi:10.2307/1291833.

The traction trebuchet, invented by the Chinese sometime before the fourth century B.C., was partially superseded at the beginning of the eighth century by the hybrid trebuchet. This machine appears to have originated in the realms of Islam under the impetus of the Islamic conquest movements.

- ↑ Bradbury, Jim (1992). The Medieval Siege. The Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-312-7.

- ↑ Bernsted, A.K. (2003), "Early Islamic Pottery: Materials and Techniques, London: Archetype Publications Ltd., 25; R.B. Mason and M.S. Tite 1994, The Beginnings of Islamic Stonepaste Technology", Archaeometry, 36 (1): 77–91, doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1994.tb00712.x.

- ↑ Mason and Tite 1994, 77.

- ↑ Mason and Tite 1994, 79-80.

- ↑ Caiger-Smith, 1973, p.65

- ↑ Weinberg, Bennett Alan; Bonnie K. Bealer (2001), The world of caffeine, Routledge, pp. Page 3–4, ISBN 978-0-415-92723-9

- ↑ Ireland, Corydon. Gazette "Of the bean I sing" Check

|url=value (help). Retrieved 21 July 2011. - ↑ John K. Francis. "Coffea arabica L. RUBIACEAE" (PDF). Factsheet of U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Retrieved 2007-07-27.

- ↑ Meyers, Hannah (2005-03-07). ""Suave Molecules of Mocha" -- Coffee, Chemistry, and Civilization". Archived from the original on 9 March 2005. Retrieved 2007-02-03.

- ↑ Tite, M.S. (1989), "Iznik Pottery: An Investigation of the Methods of Production", Archaeometry, 31 (2): 115–132, doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1989.tb01008.x.

- ↑ Tite 1989, 120.

- ↑ Tite 1989, 129.

- ↑ Tite 1989, 120, 123.

- ↑ Razpush, Shahnaz (15 December 2000). "ḠALYĀN". Encyclopedia Iranica. pp. 261–265. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ Sivaramakrishnan, V. M. (2001). Tobacco and Areca Nut. Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan. pp. 4–5. ISBN 81-250-2013-6.

- ↑ Blechynden, Kathleen (1905). Calcutta, Past and Present. Los Angeles: University of California. p. 215.

- ↑ Rousselet, Louis (1875). India and Its Native Princes: Travels in Central India and in the Presidencies of Bombay and Bengal. London: Chapman and Hall. p. 290.

- ↑ Bowles, Edmund A. (2006), "The impact of Turkish military bands on European court festivals in the 17th and 18th centuries", Early Music, Oxford University Press, 34 (4): 533–60, doi:10.1093/em/cal103

External links

- Qatar Digital Library - an online portal providing access to previously digitised British Library archive materials relating to Gulf history and Arabic science

- 1001 Inventions: Discover The Muslim Heritage In Our World

- "How Greek Science Passed to the Arabs" by De Lacy O'Leary

This article is issued from

Wikipedia.

The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike.

Additional terms may apply for the media files.