Halicarnassus

|

Ἁλικαρνασσός or Ἀλικαρνασσός (in Ancient Greek) Halikarnas (in Turkish) | |

The ruins of the Mausoleum of Maussollos, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. | |

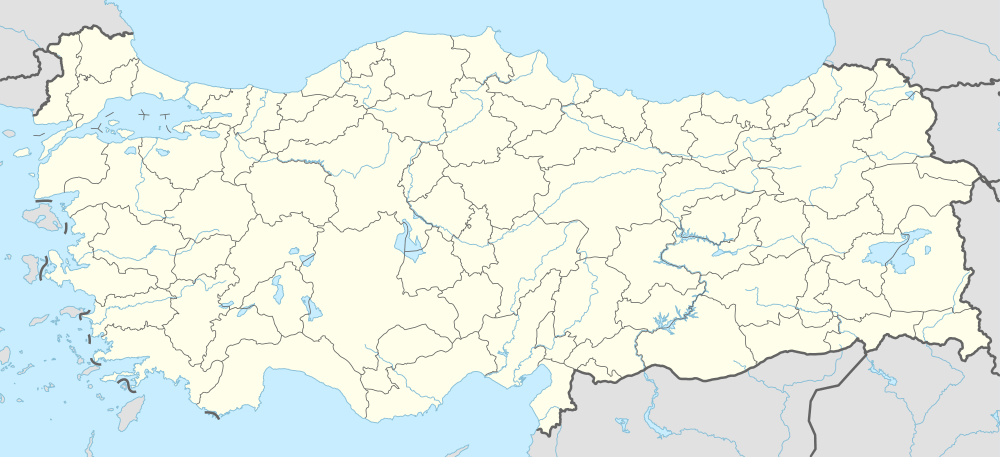

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Bodrum, Muğla Province, Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Caria |

| Coordinates | 37°02′16″N 27°25′27″E / 37.03778°N 27.42417°ECoordinates: 37°02′16″N 27°25′27″E / 37.03778°N 27.42417°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Associated with | Herodotus |

Halicarnassus (/ˌhælɪkɑːrˈnæsəs/; Ancient Greek: Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός Halikarnāssós or Ἀλικαρνασσός Alikarnāssós; Turkish: Halikarnas) was an ancient Greek city at what is now Bodrum in Turkey. It was located in southwest Caria on a picturesque, advantageous site on the Ceramic Gulf.[1] The city was famous for the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, also known simply as the Tomb of Mausolus, whose name provided the origin of the word "mausoleum". The mausoleum, built from 353 to 350 BC, ranked as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Halicarnassus' history was special on two interlinked issues. Halicarnassus retained a monarchical system of government at a time when most other Greek city states have long since gotten rid of their kings. And secondly, while their Ionian neighbours rebelled against Persian rule, Halicarnasassus remained loyal to the Persian and was formed part of the Persian Empire until Alexander the Great captured it at the siege of Halicarnassus in 334 BC.

Halicarnassus originally occupied only a small island near to the shore called Zephyria, which was the original name of the settlement and the present site of the great Castle of St. Peter built by the Knights of Rhodes in 1404. However, in the course of time, the island united with the mainland, and the city was extended to incorporate Salmacis, an older town of the Leleges and Carians[1] and site of the later citadel.

Etymology

The suffix -ᾱσσός (-assos) of Greek Ἁλικαρνᾱσσός is indicative of a substrate toponym, meaning that an original Greek name influenced, or established the place's name. It has been recently proposed that the element -καρνᾱσσός is cognate (essentially two words in different languages derived from the same original source) with Luwian (CASTRUM)ha+ra/i-na-sà / (CASTRUM)ha+ra/i-ni-sà 'fortress'.[2] If so, the toponym is probably borrowed from Carian, a Luwic language spoken alongside Greek in Halicarnassus. The Carian name for Halicarnassus has been tentatively identified with Alos-δ karnos-δ in inscriptions.

History

Mycenaean presence in the area

Some large Mycenaean tombs have been found at Musgebi (or Muskebi, modern Ortakent), not far from Halicarnassus. According to Turkish archaeologist Yusuf Boysal, the Muskebi material, dating from the end of the fifteenth century BC to ca. 1200 BC, provides evidence of the presence, in this region, of a Mycenaean settlement.[3]

More than forty burial places dating back to that time have been discovered. A rich collection of artifacts found in these tombs is now housed in the Bodrum Castle.

These finds cast some light on the problem of determining the territories of ancient Arzawa and Ahhiyawa.[3]

Early history

The founding of Halicarnassus is debated among various traditions; but they agree in the main point as to its being a Dorian colony, and the figures on its coins, such as the head of Medusa, Athena or Poseidon, or the trident, support the statement that the mother cities were Troezen and Argos. The inhabitants appear to have accepted Anthes, a son of Poseidon, as their legendary founder, as mentioned by Strabo, and were proud of the title of Antheadae.[1]

At an early period Halicarnassus was a member of the Doric Hexapolis, which included Kos, Cnidus, Lindos, Kameiros and Ialysus; but it was expelled from the league when one of its citizens, Agasicles, took home the prize tripod which he had won in the Triopian games, instead of dedicating it according to custom to the Triopian Apollo. In the early 5th century Halicarnassus was under the sway of Artemisia I of Caria (also known as Artemesia of Halicarnassus), who made herself famous as a naval commander at the battle of Salamis. Of Pisindalis, her son and successor, little is known; but Lygdamis, who next attained power, is notorious for having put to death the poet Panyasis and causing Herodotus, possibly the best known Halicarnassian, to leave his native city (c. 457 BC).[4][1]

Hekatomnid dynasty

Hecatomnus became king of Caria, at that time part of the Persian Empire, ruling from 404 BC to 358 BC and establishing the Hekatomnid dynasty. He left three sons, Mausolus, Idrieus and Pixodarus—all of whom—in their turn, succeeded him in the sovereignty; and two daughters, Artemisia and Ada, who were married to their brothers Mausolus and Idrieus.

Mausolus moved his capital from Mylasa to Halicarnassus. His workmen deepened the city's harbor and used the dragged sand to make protecting breakwaters in front of the channel.[5] On land they paved streets and squares, and built houses for ordinary citizens. And on one side of the harbor they built a massive fortified palace for Mausolus, positioned to have clear views out to sea and inland to the hills—places from where enemies could attack. On land, the workmen also built walls and watchtowers, a Greek–style theatre and a temple to Ares—the Greek god of war.

Artemisia and Mausolus spent huge amounts of tax money to embellish the city. They commissioned statues, temples and buildings of gleaming marble. When he died in 353 BC, his wife, sister and successor, Artemisia II of Caria, began construction of a magnificent tomb for him and herself on a hill overlooking the city. She died in 351 BC (of grief, according to Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 3.31). According to Pliny the Elder the craftsmen continued to work on the tomb after the death of their patron, "considering that it was at once a memorial of his own fame and of the sculptor's art," finishing it in 350 BC. This tomb of Mausolus came to be known as the Mausoleum, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

Artemisia was succeeded by her brother Idrieus, who, in turn, was succeeded by his wife and sister Ada when he died in 344 BC. However, Ada was usurped by her brother Pixodarus in 340 BC. On the death of Pixodarus in 335 BC his son-in-law, a Persian named Orontobates, received the satrapy of Caria from Darius III of Persia.

Alexander the Great and Ada of Caria

When Alexander the Great entered Caria in 334 BC, Ada, who was in possession of the fortress of Alinda, surrendered the fortress to him. After taking Halicarnassus, Alexander handed back the government of Caria to her; she, in turn, formally adopted Alexander as her son, ensuring that the rule of Caria passed unconditionally to him upon her eventual death. During the siege of Halicarnassus the city was fired by the retreating Persians. As he was not able to reduce the citadel, Alexander was forced to leave it blockaded.[1] The ruins of this citadel and moat are now a tourist attraction in Bodrum.

Later history

Not long afterwards the citizens received the present of a gymnasium from Ptolemy and built in his honour a stoa or portico.[1] Under Egyptian hegemony, around 268 BC, a citizen named Hermias became Nesiarch of the Nesiotic League in the Cyclades.[6]

Halicarnassus never recovered altogether from the disasters of the siege, and Cicero describes it as almost deserted.[1]

Baroque artist Johann Elias Ridinger depicted the several stages of siege and taking of the place in a huge copper engraving as one of only two known today from his Alexander set.

The Christian and later history of the site is continued at Bodrum.

Archeological notes and restorations

The site is now occupied in part by the town of Bodrum; but the ancient walls can still be traced round nearly all their circuit, and the position of several of the temples, the theatre, and other public buildings can be fixed with certainty.[1]

The ruins of the mausoleum were recovered sufficiently by the 1857 excavations of Charles Newton to enable a fairly complete restoration of its design to be made. The building consisted of five parts—a basement or podium, a pteron or enclosure of columns, a pyramid, a pedestal and a chariot group. The basement, covering an area of 114 feet by 92, was built of blocks of greenstone, cased with marble and covered in carvings of cows. Round the base of it were probably disposed groups of statuary. The pteron consisted (according to Pliny) of thirty-six columns of the Ionic order, enclosing a square cella. Between the columns probably stood single statues. From the portions that have been recovered, it appears that the principal frieze of the pteron represented combats of Greeks and Amazons. In addition, there are also many life-size fragments of animals, horsemen, etc., belonging probably to pedimental sculptures, but formerly supposed to be parts of minor friezes. Above the pteron rose the pyramid, mounting by 24 steps to an apex or pedestal.[1]

On this apex stood the chariot with the figure of Mausolus himself and an attendant. The height of the statue of Mausolus in the British Museum is 9'9" without the plinth. The hair falls from the forehead in thick waves on each side of the face and descends nearly to the shoulder; the beard is short and close, the face square and massive, the eyes deep set under overhanging brows, the mouth well formed with settled calm about the lips. The drapery is grandly composed. All sorts of restorations of this famous monument have been proposed. The original one, made by Newton and Pullan, is obviously in error in many respects; and that of Oldfield, though to be preferred for its lightness (the mausoleum was said anciently to be "suspended in mid-air"), does not satisfy the conditions postulated by the remains. The best on the whole is that of the veteran German architect, F. Adler, published in 1900; but fresh studies have since been made (see below).[1]

Notable people

- Artemisia I (fl. 480 BC), Queen of Halicarnassus, who participated in the Battle of Salamis[7]

- Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BC), Greek historian[8]

- Dionysius (c. 60 - 8 BC), historian and teacher of rhetoric[9]

- Aelius Dionysius (fl. 2nd century), Greek rhetorician and musician

Notes and references

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

- ↑ Ilya Yakubovich. "Phoenician and Luwian in Early Age Cilicia". Anatolian Studies 65 (2015): 44, doi:10.1017/S0066154615000010 Archived 2016-09-23 at the Wayback Machine..

- 1 2 Yusuf Boysal, New Excavations in Caria (PDF), Anadolu, (1967), 32–56.

- ↑ "Herodotus". Suda. At the Suda On Line Project.

- ↑ premiumtravel. "Bodrum - Premium Travel". premiumtravel.net. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ↑ C. Constantakopoulou, Identity and resistance: The Islanders’ League, the Aegean islands and the Hellenistic kings, in: Mediterranean Historical Review, Vol. 27, No. 1, June 2012, 49–70, note 49 Archived 2018-05-03 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Salowey, Christina A.; Magill, Frank Northen (2004). Great Lives from History: Aaron-Lysippus. Salem Press. p. 109. ISBN 9781587651533.

- ↑ Berit, Ase; Strandskogen, Rolf (26 May 2015). Lifelines in World History: The Ancient World, The Medieval World, The Early Modern World, The Modern World. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781317466048.

- ↑ Matsen, Patricia P.; Rollinson, Philip B.; Sousa, Marion (1990). Readings from Classical Rhetoric. SIU Press. p. 291. ISBN 9780809315932.

Bibliography

- Cook, B. F., Bernard Ashmole, and Donald Emrys Strong. 2005. Relief Sculpture of the Mausoleum At Halicarnassus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dinsmoor, William B. (1908). "The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus". American Journal of Archaeology. 12: 3–29, 141–197. doi:10.2307/496853.

- F. Adler, F. (1900). "Das Mausoleum zu Halikarnass" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Bauwesen. 50: 2–19.

- Fergusson, James (1862). The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus restored in conformity with the recently discovered remains. London: J. Murry.

- Jeppeson, Kristian. 2002. The Maussolleion at Halikarnassos: Reports of the Danish archaeological expedition to Bodrum: The superstructure, a comparative analysis of the architectural, sculptural, and literary evidence. Vol. 5. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus Univ. Press.

- Newton, Charles Thomas; Pullan, Richard Popplewell (1862–1863). A history of discoveries at Halicarnassus, Cnidus & Branchidæ (2 Vols). London: Day and Son. . Google books: Volume 1, Volume 2.

- Oldfield, Edmund (1895). "The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. A new restoration". Archaeologia. 54: 273–362. doi:10.1017/s0261340900018051.

- Oldfield, Edmund (1897). "The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. The probable arrangement and signification of its principal sculptures". Archaeologia. 55: 343–390. doi:10.1017/s0261340900014417.

- Preedy, J. B. Knowlton (1910). "The Chariot Group of the Maussolleum". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 30: 133–162. JSTOR 624266.

- Rodríguez Moya, Inmaculada, and Víctor Mínguez. 2017. The Seven Ancient Wonders In the Early Modern World. New York: Routledge.

- Six, J. (1905). "The pediments of the Maussolleum". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 25: 1–13. doi:10.2307/624205.

- Steele, James, and Ersin Alok. 1992. Hellenistic Architecture In Asia Minor. London: Academy Editions.

- Stevenson, John James (1909). A restoration of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. London: B. T. Batsford.

- Wiater, Nicolas. 2011. The Ideology of Classicism: Language, History, and Identity In Dionysius of Halicarnassus. New York: De Gruyter.

- Winter, Frederick E. 2006. Studies In Hellenistic Architecture. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Halicarnassus. |

| Library resources about Halicarnassus |

- Livius, Halicarnassus by Jona Lendering.

- The Tomb of Mausolus W. R. Lethaby's reconstruction of the Mausoleum, 1908.

- Mausoleum Article from Smith's Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, 1875.