Melid

Melid/Arslantepe | |

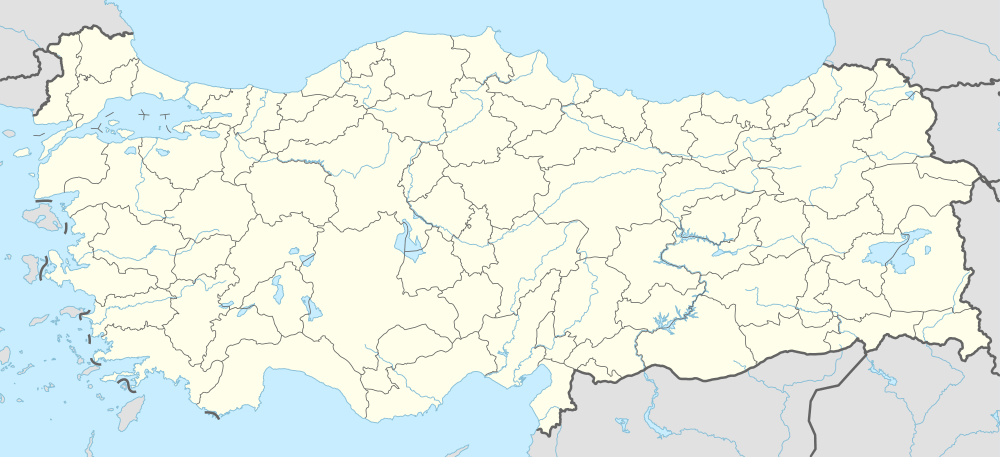

Shown within Turkey | |

| Location | Turkey |

|---|---|

| Region | Malatya Province |

| Coordinates | 38°22′55″N 38°21′40″E / 38.38194°N 38.36111°ECoordinates: 38°22′55″N 38°21′40″E / 38.38194°N 38.36111°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

Melid (Hittite: Malidiya[1] and possibly also Midduwa;[2] Akkadian: Meliddu;[3] Urartian: Melitea; Latin: Melitene) was an ancient city on the Tohma River, a tributary of the upper Euphrates rising in the Taurus Mountains. It has been identified with modern archaeological site Arslantepe near Malatya, Turkey.

History

Earliest habitation at the site dates back to the Chalcolithic period.[4] By the Uruk period development had grown to include a large temple/palace complex.[5] Around 3000 BCE, there was widespread burning and destruction, after which Kura-Araxes culture pottery appeared in the area. This was a mainly pastoralist culture connected with Caucasus mountains.[6]

Numerous similarities have been found between these early layers at Arslantepe, and the somewhat later site of Birecik (Birecik Dam Cemetery), also in Turkey, to the southwest of Melid.[7]

From the Bronze Age the site became an administrative center of a larger region in the kingdom of Isuwa. The city was heavily fortified, probably due to the Hittite threat from the west. The Hittites conquered the city in the fourteenth century BC. In the mid 14th century BC, Melid was the base of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I on his campaign to sack the Mitanni capital Wassukanni.

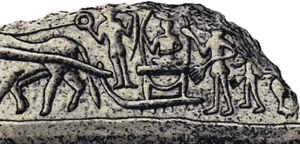

After the end of the Hittite empire, from the 12th to 7th century BC, the city became the center of an independent Luwian Neo-Hittite state of Kammanu. A palace was built and monumental stone sculptures of lions and the ruler erected.

The encounter with the Assyrian king of Tiglath-Pileser I (1115-1077 BC) resulted in the kingdom of Melid being forced to pay tribute to Assyria. Melid remained able to prosper until the Assyrian king Sargon II (722-705 BC) sacked the city in 712 BC.[8] At the same time, the Cimmerians and Scythians invaded Anatolia and the city declined.

Archaeology

Arslantepe was first investigated by the French archaeologist Louis Delaporte from 1932 to 1939. [9] [10] [11] From 1946 to 1951 Claude F.A. Schaeffer carried out some soundings. The first Italian excavations at the site of Arslantepe started in 1961, and were conducted under the direction of Professors Piero Meriggi and Salvatore M. Puglisi until 1968. [12] [13] [14] The choice of the site was initially due to their desire of investigating the Neo-Hittite phases of occupation at the site, period in which Malatya was the capital of one of the most important reigns born after the destruction of the Hittite Empire in its most eastern borders. Majestic remains of this period were known from Arslantepe since the 30s, brought to light by a French expedition. The Hittitologist Meriggi only took part of the first few campaigns and later left the direction to Puglisi, a palaeoethnologist, who expanded and regularly conducted yearly investigations under regular permit from the Turkish government. Alba Palmieri took over the supervision of the excavation during the 1970s. [15] [16] Today the archaeological investigation is led by Marcella Frangipane.[17]

Early swords

The first swords known in the Early Bronze Age (c. 33rd to 31st centuries) are based on finds at Arslantepe by Marcella Frangipane of Rome University.[18][19][20] A cache of nine swords and daggers was found; they are composed of arsenic-copper alloy. Among them, three swords were beautifully inlaid with silver.

These weapons have a total length of 45 to 60 cm which suggests their description as either short swords or long daggers.

These discoveries were made back in the 1980s. They belong to the local phase VI A. Also, 12 spearheads were found.

Phase VI A at Arslantepe ended in destruction--the city was burned. Later on, some new occupants also left some bronze weapons, including swords. They were found in the rich tomb of "Signori Arslantepe" or "Signor Arslantepe", as he was called by archaeologists. He was about 40 years old, and the tomb is radiocarbon dated to 3081-2897 (95% probabiity).[21]

Notes

- ↑ "Melid." Reallexikon der Assyriologie. Accessed 12 Dec 2010.

- ↑ KBo V 8 IV 18. Op. cit. Puhvel, Jaan. Trends in Linguistics: Hittite Etymological Dictionary: Vol. 6: Words Beginning with M. Walter de Gruyter, 2004. Accessed 12 Dec 2010.

- ↑ Hawkins, John D. Corpus of Hieroglyphic Luwian Inscriptions. Vol. 1: Inscriptions of the Iron Age. Walter de Gruyter, 2000.

- ↑ Frangipane Marcella. The Late Chalcolithic IEB I sequence at Arslantepe. Chronological and cultural remarks from a frontier site. In: Chronologies des pays du Caucase et de l’Euphrate aux IVe-IIIe millénaires. From the Euphrates to the Caucasus: Chronologies for the 4th-3rd millennium B.C. Vom Euphrat in den Kaukasus: Vergleichende Chronologie des 4. und 3. Jahrtausends v. Chr. Actes du Colloque d’Istanbul, 16-19 décembre 1998. Istanbul : Institut Français d'Études Anatoliennes-Georges Dumézil, pp. 439-471, 2000

- ↑ Frangipane Marcella. A 4th-millennium temple/palace complex at Arslantepe-Malatya. North-South relations and the formation of early state societies in the Northern regions of Greater Mesopotamia.. In: Paléorient, vol. 23, no. 1. pp. 45-73, 1997

- ↑ Frangipane, Marcella (2015). "Different types of multiethnic societies and different patterns of development and change in the prehistoric Near East". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (30): 9182–9189. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419883112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4522825. PMID 26015583.

- ↑ Schmidt-Schultz Tyedje, Schultz Michael, Sadori Laura, Palmieri A., Morbidelli Paola, Hauptmann Andreas, Di Nocera Gian Maria, Frangipane Marcella, New Symbols of a New Power in a "Royal" Tomb from 3 000 BC Arslantepe, Malatya (Turkey). Paléorient, 2001, vol. 27, n°2. pp. 105-139

- ↑ J. D. Hawkins, Assyrians and Hittites, Iraq, vol. 36, no. 1/2, pp. 67-83, 1974

- ↑ Louis De Laporte, Malatya. La Ville et le Pays de Malatya, Review Hittites et Asian, vol. 2, no. 12, pp. 119-254, 1933

- ↑ Louis De Laporte, Malatya - Céramique du Hittite Recent, Review Hittites et Asian, vol. 2, no. 15, pp. 257-285, 1934

- ↑ Louis De Laporte, La Troisième Campagne de Fouille è Malatya, Review Hittites et Asian, vol. 5, no. 34, pp. 43-56, 1939

- ↑ S.M. Puglisi and P. Meriggi, Malatya I: Rapporto preliminare delle Campagne 1961 e 1962, Orientis Antiqui Collectio, vol. 7, 1964

- ↑ E. Equini Schneider, Malatya II: Rapporto preliminare delle Campagne 1963-1968. Il Livello Romano Bizantino e le Testimonianze Islamiche, Orientis Antiqui Collectio, vol. 10, 1970

- ↑ P.E. Pecorella, Malatya III: Rapporto preliminare delle Campagne 1963-1968. Il Livello Eteo Imperiale e quelli Neoetei, Orientis Antiqui Collecti, vol. 12, 1975

- ↑ A. Palmieri, Excavations at Arslantepe (Malatya), Anatolian Studies, vol. 31, pp. 101-119, 1981

- ↑ Alba Palmieri, "Arslantepe Excavations,1982," Kazi Sonuçlari Toplantisi, vol. 5, pp. 97-101, 1983

- ↑ Historical Dictionary of the Hittites, pp 185-186

- ↑ Oldest Swords Found in Turkey

- ↑ Frangipane, M. et.al. 2010: The collapse of the 4th millennium centralised system at Arslantepe and the far-reaching changes in 3rd millennium societies. ORIGINI XXXIV, 2012: 237-260.

- ↑ Frangipane, "The 2002 Exploration Campaign at Arslantepe/Malatya" (2004)

- ↑ The Sword, chapter I: Birth of the Swordsman

See also

References

- Burney, Charles Allen (2004). Historical Dictionary of the Hittites. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4936-4.

- Louis De Laporte, La porte des lions, 1940