Generation X

| Part of a series on |

| Generations |

|---|

Generation X or Gen X is the demographic cohort following the baby boomers and preceding the Millennials. There are no precise dates for when Generation X starts or ends. Demographers and researchers typically use birth years ranging from the early-to-mid 1960s to the early 1980s.

Members of Generation X were children during a time of shifting societal values and as children were sometimes called the "latchkey generation", due to reduced adult supervision as children compared to previous generations, a result of increasing divorce rates and increased maternal participation in the workforce, prior to widespread availability of childcare options outside the home. As adolescents and young adults, they were dubbed the "MTV Generation" (a reference to the music video channel of the same name). In the 1990s they were sometimes characterized as slackers, cynical and disaffected. Some of the cultural influences on Gen X youth were the musical genres of punk music, heavy metal music, grunge and hip hop music, and indie films. In midlife, research describes them as active, happy, and achieving a work–life balance. The cohort has been credited with entrepreneurial tendencies.

Origin of term

The term "Generation X" has been used at various times throughout history to describe alienated youth. In the 1950s, Hungarian photographer Robert Capa used Generation X as the title for a photo-essay about young men and women growing up immediately following World War II.[1] In 1976, English musician Billy Idol used the moniker as the name for a punk rock band,[2] based on the title of a 1965 book on popular youth culture by two British journalists, Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett.[3]

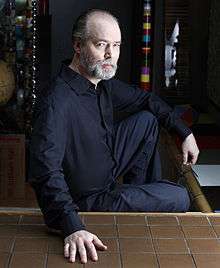

The term acquired its modern definition after the release of Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture, a 1991 novel written by Canadian author Douglas Coupland. Demographer Neil Howe noted the delay in naming this demographic cohort saying, "Over 30 years after their birthday, they didn't have a name. I think that's germane." Previously, the cohort had been referred to as Post-Boomers, Baby Busters, New Lost Generation, latchkey kids, MTV Generation, and the 13th Generation (the 13th generation since American independence).[2][4][5][6][7]

Demographer William Strauss observed that Coupland applied the term to older members of the cohort born between 1961 and 1964, who were sometimes told by demographers that they were baby boomers, but who did not feel like boomers. Strauss also noted that around the time Coupland's 1991 novel was published the symbol "X" was prominent in popular culture, as the film Malcolm X was released in 1992, and that the name "Generation X" ended up sticking. The "X" refers to an unknown variable or to a desire not to be defined.[4][8][9]

Birth dates

Generation X is the demographic cohort following the post–World War II baby boom, representing a generational change from the baby boomers, but there is debate over what this means because the end-date of the baby-boomer generation is disputed. Research from MetLife, examining the boomers, split their cohort into "older boomers", which they defined as born between 1946 and 1955, and "younger boomers", which they defined as born between 1956 and 1964. They found much of the cultural identity of the baby-boomer generation is associated with the "older boomers", while half of the "younger boomers" were averse to being associated with the baby-boomer cohort and a third of those born between 1956 and 1964 actively identified as members of Generation X.[10]

Demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe rejected the frequently used 1964 end-date of the baby-boomer cohort (which results in a 1965 start-year for Generation X), saying that a majority of those born between 1961 and 1964 do not self-identify as boomers, and that they are culturally distinct from boomers in terms of shared historical experiences. Howe says that while many demographers use 1965 as a start date for Generation X, this is a statement about fertility in the population (birth-rates which began declining in 1957, declined more sharply following 1964) and fails to take into consideration the shared history and cultural identity of the individuals. Strauss and Howe define Generation X as those born between 1961 and 1981.[11][12][13][14]

Many researchers and demographers continue to use dates which correspond to the strict fertility-patterns in the population, which results in a Generation X starting-date of 1965, such as Pew Research Center which uses a range of 1965–1980,[15] MetLife which uses 1965–1976,[4] Australia's McCrindle Research Center which uses 1965–1979,[16] and Gallup which also uses 1965–1979.[17]

Others use dates similar to Strauss and Howe's such as the National Science Foundation's Generation X Report, a quarterly research report from The Longitudinal Study of American Youth, which defines Generation X as those born between 1961 and 1981.[18] Generation X, a six-part 2016 documentary series produced by National Geographic also uses a 1961–1981 birth year range.[19][20] PricewaterhouseCoopers, a multinational professional services network headquartered in London, describes Generation X employees as those born from the early 1960s to the early 1980s.[21]

Author Jeff Gordinier, in his 2008 book X Saves the World, defines Generation X as those born roughly between 1961 and 1977 but possibly as late as 1980.[22] Canadian author and professor David Foot divides the post-boomer generation into two groups: Generation X, born between 1960 and 1966; and the "Bust Generation", born between 1967 and 1979, In his book Boom Bust & Echo: How to Profit from the Coming Demographic Shift.[23][24] On the American television program Survivor, for their 33rd season, subtitled Millennials vs. Gen X, the "Gen X tribe" consisted of individuals born between 1963 and 1982.[25]

Other demographers and researchers use a wide range of dates to describe Generation X, with the beginning birth-year ranging from as early as 1960[26][27] to as late as 1965,[16] and with the final birth year ranging from as early as 1976[28] to as late as 1984.[29][30] Due in part to the frequent birth-year overlap and resulting incongruence existing between attempts to define Generation X and Millennials, a number of individuals born in the late 1970s or early 1980s see themselves as being on the cusp "between" the two generations.[31][32][33][34] Names given to those born on the Generation X/Millennial cusp years include Xennials, The Lucky Ones, Generation Catalano, and the Oregon Trail Generation.[34][35][36][37][38]

Demographics

United States

A 2010 Census report counted approximately 84 million people living in the U.S. who are defined by birth years ranging from the early 1960s to the early 80s.[39] In a 2012 article for the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, George Masnick wrote that the "Census counted 82.1 million" Gen Xers in the U.S. The Harvard Center uses 1965 to 1984 to define Gen X so that Boomers, Xers, and Millennials "cover equal 20-year age spans".[29] Masnick concluded that immigration filled in any birth year deficits during low fertility years of the late 1960s and early 1970s.[29]

Jon Miller at the Longitudinal Study of American Youth at the University of Michigan wrote that "Generation X refers to adults born between 1961 and 1981" and it "includes 84 million people".[40]

In their 1991 book "Generations" authors and demographers Neil Howe and William Strauss, used 1961 to 1981 for Gen X birth years. At the time it was published they wrote that there are approximately 88.5 million U.S. Gen Xers.[41]

The birth control pill, introduced in the early 1960s, was one contributing factor of declining birth rates seen in the late 1960s and 70s. However, increased immigration partially offset declining birth rates and contributed to making Generation X an ethnically and culturally diverse demographic cohort.[2][30]

As children and adolescents

Demographers William Strauss and Neil Howe, who authored several books on generations, including the 1993 book, 13th Gen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail?, specifically on Generation X reported that Gen Xers were children at a time when society was less focused on children and more focused on adults.[13] Gen Xers were children during a time of increasing divorce rates, with divorce rates doubling in the mid-1960s, before peaking in 1980.[2][42][43] Strauss and Howe described a cultural shift where the long-held societal value of staying together for the sake of the children was replaced with a societal value of parental and individual self-actualization. Strauss wrote that society "moved from what Leslie Fiedler called a 1950s-era 'cult of the child' to what Landon Jones called a 1970s-era 'cult of the adult'."[13][44] The Generation Map, a report from Australia's McCrindle Research Center writes of Gen X children: "their Boomer parents were the most divorced generation in Australian history".[45]

The Gen X childhood coincided with the sexual revolution, which Susan Gregory Thomas described in her book In Spite of Everything as confusing and frightening for children in cases where a parent would bring new sexual partners into their home. Thomas also discussed how divorce was different during the Gen X childhood, with the child having a limited or severed relationship with one parent following divorce, often the father, due to differing societal and legal expectations. In the 1970s, only 9 U.S states allowed for joint custody of children, which has since been adopted by all 50 states following a push for joint custody during the mid-1980s.[46][47]

The time period of the Gen X childhood saw an increase in latchkey children, leading to the terminology of the "latchkey generation" for Generation X.[48][49][50] These latchkey children lacked adult supervision in the hours between the end of the school day and when a parent returned home from work in the evening, and for longer periods of time during the summer. Latchkey children became common among all socioeconomic demographics, but were particularly common among middle and upper class children. The higher the educational attainment of the parents, the higher the odds the children of this time would be latchkey children, due to increased maternal participation in the workforce at a time before childcare options outside the home were widely available.[49][51][52][53][54][55] McCrindle Research Center described the cohort as "the first to grow up without a large adult presence, with both parents working", stating this led to Gen Xers being more peer-oriented than previous generations.[45]

The United Kingdom's Economic and Social Research Council described Generation X as "Thatcher's children" because the cohort grew up while Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990, "a time of social flux and transformation".[56] In South Africa, Gen Xers spent their formative years of the 1980s during the "hyper-politicized environment of the final years of apartheid".[57] In the US, Generation X was the first cohort to grow up post-integration. They were described in a marketing report by Specialty Retail as the kids who "lived the civil rights movement." They were among the first children to be bused to attain integration in the public school system. In the 1990s, Strauss reported Gen Xers were "by any measure the least racist of today's generations".[58][59] In the US, Title IX, which passed in 1972, provided increased athletic opportunities to Gen X girls in the public school setting.[60] In Russia, Generation Xers are referred to as "the last Soviet children", as the last children to come of age prior to the downfall of communism in their nation and prior to the fall of the Soviet Union.[16]

Politically, in the United States, the Gen X childhood coincided with a time when government funding tended to be diverted away from programs for children and often instead directed toward the elderly population, with cuts to Medicaid and programs for children and young families, and protection and expansion of Medicare and Social Security for the elderly population. One in five American children grew up in poverty during this time. These programs for the elderly were not tied to economic need. Congressman David Durenberger criticized this political situation, stating that while programs for poor children and for young families were cut, the government provided "free health care to elderly millionaires".[58][61]

Gen Xers came of age or were children during the crack epidemic, which disproportionately impacted urban areas and also the African-American community in the US. Drug turf battles increased violent crime, and crack addiction impacted communities and families. Between 1984 and 1989, the homicide rate for black males aged 14 to 17 doubled in the US, and the homicide rate for black males aged 18 to 24 increased almost as much. The crack epidemic had a destabilizing impact on families with an increase in the number of children in foster care.[62][63] Generation X was the first cohort to come of age with MTV and are sometimes called the MTV Generation.[64][65] They experienced the emergence of music videos, grunge, alternative rock and hip hop.[66]

The emergence of AIDS coincided with Gen X's adolescence, with the disease first clinically observed in the United States in 1981. By 1985, an estimated one to two million Americans were HIV positive. As the virus spread, at a time before effective treatments were available, a public panic ensued. Sex education programs in schools were adapted to address the AIDS epidemic which taught Gen X students that sex could kill you.[67][68] Gen Xers were the first children to have access to computers in their homes and schools.[45] Generally, Gen Xers are the children of the Silent Generation and older Baby Boomers.[22][45]

As young adults

In the 1990s, media pundits and advertisers struggled to define the cohort, typically portraying them as "unfocused twentysomethings". A MetLife report noted: "media would portray them as the Friends generation: rather self-involved and perhaps aimless...but fun." [64][69] In France, Gen Xers were sometimes referred to as 'Génération Bof' because of their tendency to use the word 'bof', which translated into English means 'whatever".[16] Gen Xers were often portrayed as apathetic or as "slackers", a stereotype which was initially tied to Richard Linklater's comedic and essentially plotless 1991 film Slacker. After the film was released, "journalists and critics thought they put a finger on what was different about these young adults in that 'they were reluctant to grow up' and 'disdainful of earnest action'."[69][70]

Stereotypes of Gen X young adults also included that they were "bleak, cynical, and disaffected". Such stereotypes prompted sociological research at Stanford University to study the accuracy of the characterization of Gen X young adults as cynical and disaffected. Using the national General Social Survey, the researchers compared answers to identical survey questions asked of 18–29-year-olds in three different time periods. Additionally, they compared how older adults answered the same survey questions over time. The surveys showed 18–29-year-old Gen Xers did exhibit higher levels of cynicism and disaffection than previous cohorts of 18–29-year-olds surveyed; however, they also found that cynicism and disaffection had increased among all age groups surveyed over time, not just young adults, making this a period effect, not a cohort effect. In other words, adults of all ages were more cynical and disaffected in the 1990s, not just Generation X.[71][72]

In 1990, Time magazine published an article titled "Living: Proceeding with Caution", which described those in their 20s as aimless and unfocused; however, in 1997, they published an article titled "Generation X Reconsidered", which retracted the previously reported negative stereotypes and reported positive accomplishments, citing Gen Xers' tendency to found technology start-ups and small businesses as well as Gen Xers' ambition, which research showed was higher among Gen X young adults than older generations.[69][73][74] As the 1990s and 2000s progressed, Gen X gained a reputation for entrepreneurship. In 1999, The New York Times dubbed them "Generation 1099", describing them as the "once pitied but now envied group of self-employed workers whose income is reported to the Internal Revenue Service not on a W-2 form, but on Form 1099".[75] In 2002, Time magazine published an article titled Gen Xers Aren't Slackers After All, reporting four out of five new businesses were the work of Gen Xers.[59][76]

In 2001, sociologist Mike Males reported confidence and optimism common among the cohort saying "surveys consistently find 80% to 90% of Gen Xers self-confident and optimistic."[77] In August 2001, Males wrote "these young Americans should finally get the recognition they deserve", praising the cohort and stating that "the permissively raised, universally deplored Generation X is the true 'great generation,' for it has braved a hostile social climate to reverse abysmal trends", describing them as the hardest-working group since the World War II generation, which was dubbed by Tom Brokaw as "The Greatest Generation". He reported Gen Xers' entrepreneurial tendencies helped create the high-tech industry that fueled the 1990s economic recovery.[77][78]

In the US, Gen Xers were described as the major heroes of the September 11 terrorist attacks by demographer William Strauss. The firefighters and police responding to the attacks were predominantly Generation Xers. Additionally, the leaders of the passenger revolt on United Airlines Flight 93 were predominantly Gen Xers.[73][79][80] Demographer Neil Howe reported survey data showed Gen Xers were cohabitating and getting married in increasing numbers following the terrorists attacks, with Gen X survey respondents reporting they no longer wanted to live alone.[81] In October 2001, Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote of Generation Xers: "now they could be facing the most formative events of their lives and their generation".[82] The Greensboro News & Record reported Gen Xers "felt a surge of patriotism since terrorists struck" reporting many were responding to the crisis of the terrorist attacks by giving blood, working for charities, donating to charities, and by joining the military to fight The War on Terror.[83] The Jury Expert, a publication of The American Society of Trial Consultants, reported: "Gen X members responded to the terrorist attacks with bursts of patriotism and national fervor that surprised even themselves".[73]

In midlife

Guides regarding managing multiple generations in the workforce describe Gen Xers as: independent, resourceful, self-managing, adaptable, cynical, pragmatic, skeptical of authority, and as seeking a work life balance.[64][84][85][86] In a 2007 article published in the Harvard Business Review, demographers Strauss & Howe wrote of Generation X; "They are already the greatest entrepreneurial generation in U.S. history; their high-tech savvy and marketplace resilience have helped America prosper in the era of globalization."[87] In the 2008 book, X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft but Can Still Keep Everything from Sucking, author Jeff Gordinier describes Generation X as a "dark horse demographic" which "doesn't seek the limelight". Gordiner cited examples of Gen Xers' contributions to society such as: Google, Wikipedia, Amazon.com and YouTube, arguing if Boomers had created them, "we'd never hear the end of it". In the book, Gordinier contrasts Gen Xers to Baby Boomers, saying Boomers tend to trumpet their accomplishments more than Gen Xers do, creating what he describes as "elaborate mythologies" around their achievements. Gordiner cites Steve Jobs as an example, while Gen Xers, he argues, are more likely to "just quietly do their thing".[22][88]

In 2011, survey analysis from the Longitudinal Study of American Youth found Gen Xers to be "balanced, active, and happy" in midlife (between ages of 30 and 50) and as achieving a work-life balance. The Longitudinal Study of Youth is an NIH-NIA funded study by the University of Michigan which has been studying Generation X since 1987. The study asked questions such as "Thinking about all aspects of your life, how happy are you? If zero means that you are very unhappy and 10 means that you are very happy, please rate your happiness." LSA reported that "mean level of happiness was 7.5 and the median (middle score) was 8. Only four percent of Generation X adults indicated a great deal of unhappiness (a score of three or lower). Twenty-nine percent of Generation X adults were very happy with a score of 9 or 10 on the scale."[18][89][90][91]

In terms of advocating for their children in the educational setting, demographer Neil Howe describes Gen X parents as distinct from Baby Boomer parents. Howe argues that Gen Xers are not helicopter parents, which Howe describes as a parenting style of Boomer parents of Millennials. Howe described Gen Xers instead as "stealth fighter parents", due to the tendency of Gen X parents to let minor issues go and to not hover over their children in the educational setting, but to intervene forcefully and swiftly in the event of more serious issues.[92] In 2012, the Corporation for National and Community Service ranked Gen X volunteer rates in the U.S. at "29.4% per year", the highest compared with other generations. The rankings were based on a three-year moving average between 2009 and 2011.[93][94]

In the United Kingdom, a 2016 study of over 2,500 office workers conducted by Workfront found that survey respondents of all ages selected those from Generation X as the hardest-working employees in today's workforce (chosen by 60%). Gen X was also ranked highest among fellow workers for having the strongest work ethic (chosen by 59.5%), being the most helpful (55.4%), the most skilled (54.5%), and the best troubleshooters/problem solvers (41.6%).[95][96]

In 2016, a global consumer insights project from Viacom International Media Networks and Viacom, based on over 12,000 respondents across 21 countries,[97] reported on Gen X's unconventional approach to sex, friendship and family,[98] their desire for flexibility and fulfillment at work[99] and the absence of midlife crisis for Gen Xers.[100] The project also included a 20 min documentary titled Gen X Today.[101] Pew Research, a nonpartisan American think tank, describes Generation X as intermediary between baby boomers and Millennials on multiple factors such as attitudes on political or social issues, educational attainment, and social media use.[102]

Arts and culture

Music

Gen Xers were the first cohort to come of age with MTV. They experienced the emergence of music videos and are sometimes called the MTV Generation.[64][65] Gen Xers were responsible for the alternative rock movement of the 1990s and 2000s, including the grunge subgenre.[74][103] Hip Hop and rap have also been described as defining music of the generation, including Tupac Shakur, N.W.A. and The Notorious B.I.G.[66]

Grunge

A notable example of alternative rock is grunge music and the associated subculture that developed in the Pacific Northwest of the US. Grunge song lyrics have been called the "...product of Generation X malaise".[105] Vulture commented: "the best bands arose from the boredom of latchkey kids". "People made records entirely to please themselves because there was nobody else to please" commented producer Jack Endino.[106] Grunge lyrics are typically dark, nihilistic,[107] angst-filled, anguished, and often addressing themes such as social alienation, despair and apathy.[108] The Guardian wrote that grunge "didn't recycle banal cliches but tackled weighty subjects".[109] Topics of grunge lyrics included homelessness, suicide, rape,[110] broken homes, drug addiction, self-loathing,[111] misogyny, domestic abuse and finding "meaning in an indifferent universe."[109] Grunge lyrics tended to be introspective and aimed to enable the listener to see into hidden personal issues and examine depravity in the world.[104] Notable grunge bands include: Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Hole, Stone Temple Pilots and Soundgarden.[109][112]

Hip hop

The mainstream hip hop music made in the late 1980s and early 1990s, typically by artists originating from the New York metropolitan area.[113] was characterized by its diversity, quality, innovation and influence after the genre's emergence and establishment in the previous decade.[114][115][116][117][118] There were various types of subject matter, while the music was experimental and the sampling eclectic.[119] The artists most often associated with the period are LL Cool J, Run–D.M.C., Public Enemy, the Beastie Boys, KRS-One, Eric B. & Rakim, De La Soul, Big Daddy Kane, EPMD, A Tribe Called Quest, Slick Rick, Ultramagnetic MC's,[120] and the Jungle Brothers.[121] Releases by these acts co-existed in this period with, and were as commercially viable as, those of early gangsta rap artists such as Ice-T, Geto Boys and N.W.A, the sex raps of 2 Live Crew and Too Short, and party-oriented music by acts such as Kid 'n Play, The Fat Boys, DJ Jazzy Jeff & The Fresh Prince and MC Hammer.[122]

In addition to lyrical self-glorification, hip hop was also used as a form of social protest. Lyrical content from the era often drew attention to a variety of social issues including afrocentric living, drug use, crime and violence, religion, culture, the state of the American economy, and the modern man's struggle. Conscious and political hip hop tracks of the time were a response to the effects of American capitalism and former President Reagan's conservative political economy. According to Rose Tricia, "In rap, relationships between black cultural practice, social and economic conditions, technology, sexual and racial politics, and the institution policing of the popular terrain are complex and in constant motion. Even though hip hop was used as a mechanism for different social issues it was still very complex with issues within the movement itself.[123] There was also often an emphasis on black nationalism. Hip hop artists often talked about urban poverty and the problems of alcohol, drugs, and gangs in their communities. Public Enemy's most influential song, "Fight the Power," came out at this time; the song speaks up to the government, proclaiming that people in the ghetto have freedom of speech and rights like every other American. One line in the song, "We got to pump the stuff to make us tough from the heart"[124] grabbed listeners' attention and gave them motivation to speak out for themselves.

Indie films

Gen Xers were largely responsible for the "indie film" movement of the 1990s, both as young directors and in large part as the movie audiences fueling demand for such films.[74][103] In cinema, directors Kevin Smith, Quentin Tarantino, Sofia Coppola, John Singleton, Spike Jonze, David Fincher, Steven Soderbergh,[125][126] and Richard Linklater[127][128] have been called Generation X filmmakers. Smith is most known for his View Askewniverse films, the flagship film being Clerks, which is set in New Jersey circa 1994, and focuses on two convenience-store clerks in their twenties. Linklater's Slacker similarly explores young adult characters who were interested in philosophizing.[129] While not a member of Gen X himself, director John Hughes has been recognized as having created a series of classic films with Gen X characters which "an entire generation took ownership of," including The Breakfast Club,[130][131] Sixteen Candles, Weird Science and Ferris Bueller's Day Off.[132]

Economy

United States

Studies done by the Pew Charitable Trusts, the American Enterprise Institute, the Brookings Institution, the Heritage Foundation and the Urban Institute challenged the notion that each generation will be better off than the one that preceded it.[133][134][135]

Workforce participation and income

A report titled Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well? focused on the income of males 30–39 in 2004 (those born April 1964 – March 1974). The study was released on May 25, 2007 and emphasized that this generation's men made less (by 12%) than their fathers had at that same age in 1974, thus reversing a historical trend. It concluded that per year increases in household income generated by fathers/sons have slowed (from an average of 0.9% to 0.3%), barely keeping pace with inflation. "Family incomes have risen though (over the period 1947 to 2005) because more women have gone to work",[136][137][133][138] "supporting the incomes of men, by adding a second earner to the family. And as with male income, the trend is downward".[137][133][138]

Generation Flux is a neologism and psychographic designation coined by Fast Company for American employees who need to make several changes in career throughout their working lives because of the chaotic nature of the job market following the Financial crisis of 2007–08. Those in "Generation Flux" have birth years in the ranges of Gen X and Millennials.

Entrepreneurship

According to authors Michael Hais and Morley Winograd:

Small businesses and the entrepreneurial spirit that Gen Xers embody have become one of the most popular institutions in America. There's been a recent shift in consumer behavior and Gen Xers will join the "idealist generation" in encouraging the celebration of individual effort and business risk-taking. As a result, Xers will spark a renaissance of entrepreneurship in economic life, even as overall confidence in economic institutions declines. Customers, and their needs and wants (including Millennials) will become the North Star for an entire new generation of entrepreneurs.[139]

A 2015 study by Sage Group reports Gen Xers "dominate the playing field" with respect to founding startups in the United States and Canada, with Gen Xers launching the majority (55%) of all new businesses in 2015.[140][141]

See also

References

- ↑ GenXegesis: essays on alternative youth (sub)culture By John McAllister Ulrich, Andrea L. Harris p. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Klara, Robert (4 April 2016). "5 Reasons Marketers Have Largely Overlooked Generation X". Adweek. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "The original Generation X". BBC News. 2014-03-01. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- 1 2 3 "Demographic Profile - America's Gen X" (PDF). MetLife. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ Coupland, Doug. "Generation X." Vista, 1989.

- ↑ Lipton, Lauren (10 November 1911). "The Shaping of a Shapeless Generation : Does MTV Unify a Group Known Otherwise For its Sheer Diversity?". Los Angelos Times. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Jackson, Ronald L.; Hogg, Michael A. (2010-06-29). Encyclopedia of Identity. SAGE. p. 307. ISBN 9781412951531.

- ↑ Neil Howe & William Strauss discuss the Silent Generation on Chuck Underwood's Generations. 2001. pp. 49:00.

- ↑ Ralphelson, Samantha (6 October 2014). "From GIs To Gen Z (Or Is It iGen?): How Generations Get Nicknames". NPR. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- ↑ "Boomer Bookend: Insight Into the Oldest and Youngest Boomers" (PDF). MetLife. February 2009. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Booknotes—Generations The History of Americas Future". CSPAN. 14 April 1991. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Howe, Neil (1992). Generations: The History of America's Future, 1584 to 2069. ISBN 978-0688119126.

- 1 2 3 Howe, Neil (1993). 13th Gen: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail?. Vintage. ISBN 978-0679743651.

- ↑ Strauss, William (2009). The Fourth Turning. Three Rivers Press. ASIN B001RKFU4I.

- ↑ "Millennials overtake Baby Boomers as America's largest generation". Pew Research. 25 April 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 McCrindle, Mark. "Generations Defined" (PDF). McCrindle Research Center. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Timmerman, John (29 July 2014). "How Hotels Can Engage Gen X and Millennial Guests". Gallup. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 Miller, Jon (Fall 2011). "The Generation X Report: Active, Balanced, and Happy" (PDF). Longitudinal Study of American Youth – University of Michigan. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- ↑ "National Geographic Channel's Six-Part Limited Series "Generation X," Narrated by Christian Slater, Premieres Sunday, Feb. 14, at 10/9c". Multichannel News. 29 January 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Generation X". National Geographic Channel. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Generation X Employees Struggle the Most Financially, Most Likely to Dip into Retirement Savings, According to PwC Study". PrincewaterhouseCoopers. 18 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gordinier, Jeff (27 March 2008). X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft but Can Still Keep Everything from Sucking. Viking Adult. ISBN 0670018589.

- ↑ Foot, David (1996). Boom, Bust & Echo. Macfarlane Walter & Ross. pp. 18–22. ISBN 0-921912-97-8. Archived from the original on 2007-01-29.

- ↑ Trenton, Thomas Norman (Fall 1997). "Generation X and Political Correctness: Ideological and Religious Transformation Among Students". Canadian Journal of Sociology. 22 (4): 417–36. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

In Boom, Bust & Echo, Foot (1996: 18–22) divides youth into two groups: 'Generation X' born between 1960 and 1966 and the 'Bust Generation' born between 1967 and 1979.

- ↑ Ross, Dalton (September 22, 2016). "Survivor: Millennials vs. Gen X premiere recap: 'May the Best Generation Win'". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Time Warner, Inc. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- ↑ Badtram, Gene. "Working Together: Four Generations". Enterprise Management Development Academy (EMDA). Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Robinson, Sara (10 April 2014). "What is Generation X? Maybe our last, best hope for change". Scholars & Rogues. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Thielfoldt, Diane (August 2004). "Generation X and The Millennials: What You Need to Know About Mentoring the New Generations". Law Practice Today. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Masnick, George. "Defining the Generations". Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies. Retrieved 2013-05-29.

- 1 2 Markert, John (Fall 2004). "Demographics of Age: Generational and Cohort Confusion" (PDF). Journal of Current Issues in Research & Advertising. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Ingraham, Christopher (May 5, 2015). "Five really good reasons to hate millennials". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Mukherji, Rohini (July 29, 2014). "X or Y: A View from the Cusp". APEX Public Relations. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Epstein, Leonora (July 17, 2013). "22 Signs You're Stuck Between Gen X And Millennials". BuzzFeed. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- 1 2 Garvey, Ana (May 5, 2015). "The Biggest (And Best) Difference Between Millennial and My Generation". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Fogarty, Lisa (January 7, 2016). "3 Signs you're stuck between Gen X & Millennials". SheKnows Media. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Shafrir, Doree (March 28, 2016). "Generation Catalano". Slate. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ Stankorb, Sarah (September 25, 2014). "Reasonable People Disagree about the Post-Gen X, Pre-Millennial Generation". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ↑ Garvey, Anna. "Why '80s Babies Are Different Than Other Millennials".

- ↑ "U.S. Census Age and Sex Composition: 2010" (PDF). U.S. Census. 2011-05-11. p. 4. Retrieved 2013-09-12.

- ↑ Miller, Jon (Fall 2011). "The Generation X Report: Active, Balanced, and Happy: These Young Americans are not Bowling Alone" (PDF). Longitudinal Study of American Youth – University Of Michigan. p. 1. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- ↑ William Strauss, Neil Howe (1991). Generations. New York, NY: Harper Perennial. p. 318. ISBN 0-688-11912-3.

- ↑ Dulaney, Josh (27 December 2015). "A Generation Stuck in the Middle Turns 50". PT Projects. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Dawson, Alene (25 September 2011). "Gen X women, young for their age". LA Times. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Strauss, William. "What Future Awaits Today's Youth in the New Millennium?". Angelo State University. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Generation Map" (PDF). McCrindle Research. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, Susan (22 October 2011). "All Apologies: Thank You for the 'Sorry'". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, Susan (12 July 2011). In Spite of Everything. Random House. ISBN 978-1400068821.

- ↑ Blakemore, Erin (9 November 2015). "The Latchkey Generation: How Bad Was It?". JSTOR Daily. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- 1 2 Clack, Erin. "Study probes generation gap.(Hot copy: an industry update)". HighBeam Research. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "What's The Defining Moment Of Your Generation?". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ↑ Thomas, Susan (21 October 2011). "All Apologies: Thank You for the 'Sorry'". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ "A Teacher's Guide to Generation X". Edutopia. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Thomas, Susan (9 July 2011). "The Divorce Generation". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- ↑ Toch, Thomas (19 September 1984). "The Making of 'To Save Our Schools, To Save Our Children': A Conversation With Marshall Frady". Education Week. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ Corry, John (4 September 1984). "A LOOK AT SCHOOLS IN U.S." The New York Times. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ "Thatcher's children: the lives of Generation X". Economic and Social Research Council. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ↑ Schenk, Jan (November 2010). "Locating generation X: Taste and identity in transitional South Africa" (PDF) (CSSR Working Paper No. 284). Centre For Social Science Research. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- 1 2

- 1 2 "Generation X". Specialty Retail. Summer 2003. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Underwood, Chuck. "America's Generations With Chuck Underwood - Generation X". PBS. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Holtz, Geoffrey (14 May 1995). Welcome to the Jungle: The Why Behind Generation X. St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0312132101. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Fryer, Roland (April 2006). "Measuring Crack Cocaine and Its Impact" (PDF). Harvard University Society of Fellows: 3, 66. Retrieved January 4, 2016.

- ↑ "Yuppies, Beware: Here Comes Generation X". Tulsa World. 9 July 1991. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "The MetLife Study of Gen X: The MTV Generation Moves into Mid-Life" (PDF). MetLife. April 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 Isaksen, Judy L. (2002). "Generation X". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture. Archived from the original on 2004-10-24.

- 1 2 Wilson, Carl (2011-08-04). "My So Called Adulthood". New York Times. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- ↑ "Generation X Reacts to AIDS". National Geographic Channel. 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Halkitis, Perry (2 February 2016). "The Disease That Defined My Generation". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gross, David (16 July 1990). "Living: Proceeding With Caution". Time. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ ScrIibner, Sara (11 August 2013). "Generation X gets really old: How do slackers have a midlife crisis?". Salon. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Generation X not so special: Malaise, cynicism on the rise for all age groups". Stanford University. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Oldsters Get The Gen X Feeling". SCI GOGO. 29 August 1998. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Keene, Douglas (29 November 2011). "Generation X members are "active, balanced and happy". Seriously?". The Jury Expert—The Art and Science of Litigation Advocacy. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Hornblower, Margot (9 June 1997). "Generation X Reconsidered". Time. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Ellin, Abby (15 August 1999). "PRELUDES; A Generation of Freelancers". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Chatzky, Jean (31 March 2002). "Gen Xers Aren't Slackers After All". Time. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 Males, Mike (26 August 2001). "The True 'Great Generation'". LA Times. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Reddy, Patrick (10 February 2002). "GENERATION X RECONSIDERED ; 'SLACKERS' NO MORE, TODAY'S YOUNG ADULTS HAVE FOUGHT WARS FIERCELY, REVERSED UNFORTUNATE SOCIAL TRENDS AND ARE PROVING THEMSELVES TO BE ANOTHER 'GREAT GENERATION'". The Buffalo News. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Koidin, Michelle (11 October 2001). "AFTER SEPTEMBER 11 EVENTS HAND GENERATION X A 'REAL ROLE TO PLAY'". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ↑ Koidin, Michelle (11 October 2001). "Events Hand Generation X A 'Real Role to Play'". LifeCourse Associates. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ↑ Neil Howe on Gen X and 9/11. 1:50: CNN. 2001.

- ↑ Klondin, Michelle (11 October 2001). "AFTER SEPTEMBER 11 EVENTS HAND GENERATION X A 'REAL ROLE TO PLAY'". Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

- ↑ Johnson, Maria (20 September 2001). "GREATNESS ALIVE IN GENERATION X YOUNG AMERICANS SHOW PATRIOTISM IN THE WAKE OF THE TERRORIST ATTACKS SEPT. 11". Greensboro News & Record.

- ↑ "CREATING A CULTURE OF INCLUSION -- LEVERAGING GENERATIONAL DIVERSITY: At-a-Glance" (PDF). University of Michigan. 2010. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Eames, David (6 March 2008). "Jumping the generation gap". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ White, Doug (23 December 2014). "What to Expect From Gen-X and Millennial Employees". Entrepreneur. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Howe, Neil (June 2007). "The next 20 years: How customer and workforce attitudes will evolve". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Stephey, M.J. (16 April 2008). "Gen-X: The Ignored Generation?". Time. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "NSF funds launch of a new LSAY 7th grade cohort in 2015 NIH-NIA fund continued study of original LSAY students". University of Michigan. 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ "Long-term Survey Reveals Gen Xers Are Active, Balanced and Happy". National Science Foundation. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Dawson, Alene (27 October 2011). "Study says Generation X is balanced and happy". CNN. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Howe, Neil. "Meet Mr. and Mrs. Gen X: A New Parent Generation". AASA - The School Superintendents Association. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ "Volunteering and Civic Life in America: Generation X Volunteer Rates". Corporation for National and Community Service. November 27, 2012. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ↑ "Volunteering in the United States" (PDF). Bureau of Labor Statistics – U.S. Department of Labor. February 22, 2013. p. 1. Retrieved 2013-04-20.

- ↑ Leeming, Robert (19 February 2016). "Generation X-ers found to be the best workers in the UK". HR Review. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Frith, Bek (23 February 2016). "Are generation X the UK's hardest workers?". HR Magazine. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Ashley. "Generation X's rebellious nature helped reinvent adulthood". Quartz. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "Gen X's Unconventional Approach To Sex, Friendship and Family". Viacom International Insights. 2016-09-22. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "At Work, Gen X Want Flexibility and Fulfilment More Than a Corner Office". Viacom International Insights. 2016-09-29. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ "For Gen X, Midlife Is No Crisis". Viacom International Insights. 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2016-10-20.

- ↑ Taylor, Anna (20 October 2016). "Gen X Today: The Documentary". Viacom International Insights. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ Taylor, Paul (5 June 2014). "Generation X: America's neglected 'middle child'". Pew Research. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 "Alternative Goes Mainstream". National Geographic Channel. 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- 1 2 Felix-Jager, Steven. With God on Our Side: Towards a Transformational Theology of Rock and Roll. Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2017. p. 134

- ↑ Music Cultures in the United States: An Introduction. Ed. Ellen Koskoff. Routledge, 2005. p. 359

- ↑ Jenkins, Craig (11 April 2017). "Pearl Jam Might Not Be Cool, But That Doesn't Mean They Aren't Great". Vulture. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ DiBlasi, Alex. "Grunge" in Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars and Stories that Shaped Our Culture, pp. 520–524. Edited by Jacqueline Edmondson. ABC-CLIO, 2013. p. 520

- ↑ Pearlin, Jeffrey. "A Brief History of Metal". Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- 1 2 3 McManus, Darragh (31 October 2008). "Just 20 years on, grunge seems like ancient history". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ Strong, Catherine. Grunge: Music and Memory. Routledge, 2016. p.19

- ↑ Gina Misiroglu. American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in U.S. History. Routledge, 2015. p. 343

- ↑ "Grunge". AllMusic. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ↑ "Golden Age". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Coker, Cheo H. (9 March 1995). "Slick Rick: Behind Bars". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ↑ "The '80s were golden age of hip-hop". TODAY.com.

- ↑ Green, Tony, in Wang, Oliver (ed.) Classic Material, Toronto: ECW Press, 2003. p. 132

- ↑ Jon Caramanica, "Hip-Hop's Raiders of the Lost Archives", The New York Times, June 26, 2005.

Cheo H. Coker, "Slick Rick: Behind Bars", Rolling Stone, March 9, 1995.

Lonnae O'Neal Parker, "U-Md. Senior Aaron McGruder's Edgy Hip-Hop Comic Gets Raves, but No Takers", Washington Post, Aug 20 1997. - ↑ Jake Coyle of Associated Press, "Spin magazine picks Radiohead CD as best", published in USA Today, June 19, 2005.

Cheo H. Coker, "Slick Rick: Behind Bars", Rolling Stone, March 9, 1995.

Andrew Drever, "Jungle Brothers still untamed", The Age [Australia], October 24, 2003. - ↑ Roni Sariq, "Crazy Wisdom Masters" Archived 2008-11-23 at the Wayback Machine., City Pages, April 16, 1997.

Scott Thill, "Whiteness Visible" AlterNet, May 6, 2005.

Will Hodgkinson, "Adventures on the wheels of steel", The Guardian, September 19, 2003. - ↑ Linhardt, Alex (June 10, 2004). Album Reviews: Ultramagnetic MC's: Critical Beatdown. Pitchfork. Retrieved on December 24, 2014.

- ↑ Per Coker, Hodgkinson, Drever, Thill, O'Neal Parker and Sariq above. Additionally:

Cheo H. Coker, "KRS-One: Krs-One", Rolling Stone, November 16, 1995.

Andrew Pettie, "'Where rap went wrong'", The Daily Telegraph, August 11, 2005.

Mosi Reeves, "Easy-Chair Rap", Village Voice, January 29th 2002.

Greg Kot, "Hip-Hop Below the Mainstream", Los Angeles Times, September 19, 2001.

Cheo Hodari Coker, "'It's a Beautiful Feeling'", Los Angeles Times, August 11, 1996.

Scott Mervis, "From Kool Herc to 50 Cent, the story of rap—so far", Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 15, 2004. - ↑ Bakari Kitwana,"The Cotton Club", Village Voice, June 21, 2005.

- ↑ Rose, Tricia. Black Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary American. Hanover: Wesleyan U, 1994. Print.

- ↑ Public Enemy, Lyricsdepot, May 25, 2008

- ↑ Hanson, Peter (2002). The Cinema of Generation X: A Critical Study of Films and Directors. North Carolina and London: McFarland and Company. ISBN 0-7864-1334-4.

- ↑ TIME, Magazine (1998-06-09). "MY GENERATION BELIEVES WE CAN DO ANYTHING". View Askew. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- ↑ Richard Linklater, Slacker, St Martins Griffin, 1992.

- ↑ Tasker, Yvonne (October 21, 2010). Fifty Contemporary Film Directors (page 3 65). Routledge. ISBN 0415554330.

- ↑ Russell, Dominique (March 25, 2010). Rape in Art Cinema (page 130: "In this vein, Solondz' films, while set in the present, contain an array of objects and architectural styles that evoke Generation X's childhood and adolescence. Dawn (Heather Matarazzo) wears her hair tied up in a 1970s ponytail holder with large balls, despite the fact her brother works at a 1990 Macintosh computer, in a film that came out in 1996."). Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 082642967X.

- ↑ "The Breakfast Club".

- ↑ Simple Minds. "Don't You (Forget About Me)".

- ↑ Aronchick., David. "Happy Birthday John Hughes: The Voice of My So-Called 'Lost Generation'". Huff Post Entertainment. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Isabel Sawhill, PhD; John E. Morton (2007). "Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well?" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ Steuerle, Eugene; Signe-Mary McKernan; Caroline Ratcliffe; Sisi Zhang (2013). "Lost Generations? Wealth Building Among Young Americans" (PDF). Urban Institute. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ↑ "Financial Security and Mobility – Pew Trusts".

- ↑ "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate: Women". FRED: Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. 1950 - 2018. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 "Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate: Men". FRED: Economic Data. Federal Reserve Bank of St.Louis.

- 1 2 Ellis, David (2007-05-25). "Making less than dad did". CNN. Retrieved 2010-05-03.

- ↑ Morley Winograd; Michael Hais (2012). "Why Generation X is Sparking a Renaissance in Entrepreneurship". Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- ↑ "2015 State of the Startup". sage. 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

- ↑ Iudica, David (12 September 2016). "The overlooked influence of Gen X". Yahoo Advertising. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

External links

- Author Jeff Gordinier Discusses 2008 Book: "X Saves the World"

- Generation X Goes Global: Mapping a Youth Culture in Motion, Christine Henseler, Ed.; 2012

- Generation X’s journey from jaded to sated - Published in Salon - October 1, 2013

- Gen X Today 2016 documentary by Viacom International Media Networks