History of Xinjiang

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

|

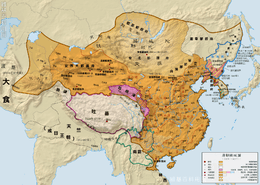

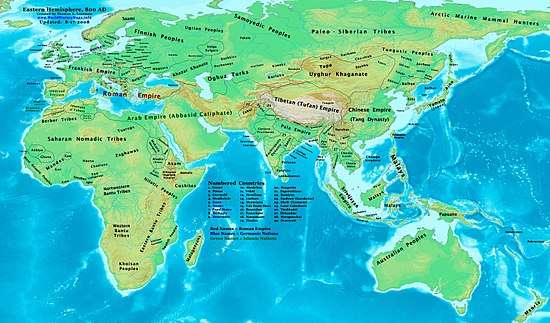

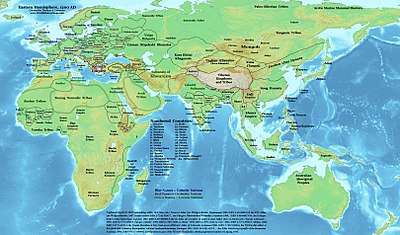

The recorded history of the area now known as Xinjiang dates to the 2nd millennium BC. There have been many empires, primarily Han Chinese, Turkic, and Mongol, that have ruled over the region, including the Yuezhi, Xiongnu, Han dynasty, Gaochang, Kingdom of Khotan, Sixteen Kingdoms of the Jin dynasty (Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, and Western Liang), Turkic Khaganate, Tang dynasty, Tibetan Empire, Uyghur Khaganate, Kara-Khanid Khanate, Kingdom of Qocho, Qara Khitai, Mongol Empire, Yuan dynasty, Chagatai Khanate, Yarkent Khanate, Dzungar Khanate, and Qing dynasty. Xinjiang was previously known as "Xiyu" (西域), under the Han dynasty, which drove the Xiongnu empire out of the region in 60 BCE in an effort to secure the profitable Silk Road,[1] but was renamed Xinjiang (新疆, meaning "new frontier") when the region was reconquered by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty in 1759. Xinjiang is now a part of the People's Republic of China, having been so since its founding year of 1949.

Background

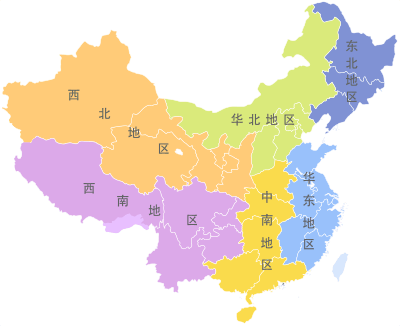

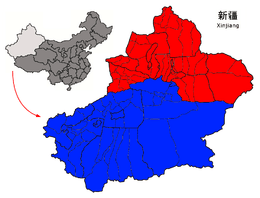

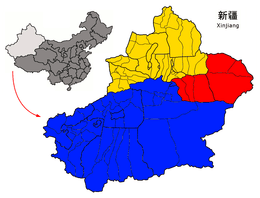

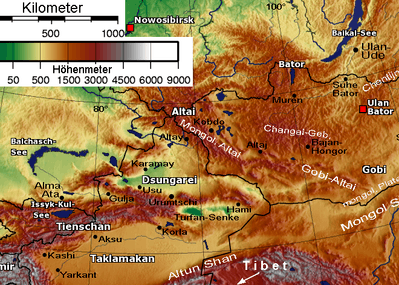

Xinjiang consists of two main geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct regions with different historical names, Dzungaria north of the Tianshan Mountains and the Tarim Basin south of the Tianshan Mountains, before Qing China unified them into one political entity called Xinjiang province in 1884. At the time of the Qing conquest in 1759, Dzungaria was inhabited by steppe dwelling, nomadic Tibetan Buddhist Oirat Mongol Dzungar people, while the Tarim Basin was inhabited by sedentary, oasis dwelling, Turkic speaking Muslim farmers, now known as the Uyghur people. They were governed separately until 1884. The native Uyghur name for the Tarim Basin is Altishahr.

The Qing dynasty was well aware of the differences between the former Buddhist Mongol area to the north of the Tianshan and Turkic Muslim south of the Tianshan, and ruled them in separate administrative units at first.[2] However, Qing people began to think of both areas as part of one distinct region called Xinjiang .[3] The very concept of Xinjiang as one distinct geographic identity was created by the Qing and it was originally not the native inhabitants who viewed it that way, but rather it was the Chinese who held that point of view.[4] During the Qing rule, no sense of "regional identity" was held by ordinary Xinjiang people; rather, Xinjiang's distinct identity was given to the region by the Qing, since it had distinct geography, history and culture, while at the same time it was created by the Chinese, multicultural, settled by Han and Hui, and separated from Central Asia for over a century and a half.[5]

In the late 19th century, it was still being proposed by some people that two separate parts be created out of Xinjiang, the area north of the Tianshan and the area south of the Tianshan, while it was being argued over whether to turn Xinjiang into a province.[6]

In ancient China, the area was known as "Xiyu" or "Western Regions", a name that became prevalent in Chinese records after the Han Dynasty took control of the region.[1][7] For the Uyghurs, the traditional name of the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang was Altishahr, which means "six cities" in the Uyghur language. The region of Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang was named after its native inhabitants, the Dzungar Mongols.

The name "East Turkestan" was created by the Russian Sinologist Nikita Bichurin to replace the term "Chinese Turkestan" in 1829.[8] "East Turkestan" was used traditionally to only refer to the Tarim Basin, and not Xinjiang as a whole, with Dzungaria being excluded from the area consisting of "East Turkestan".

After the Qing dynasty reconquered this region in 1884, the area was designated Xinjiang, which was used to refer to any area of a former Chinese empire that had been previously lost but was regained by the Qing, but eventually meant this northwestern Xinjiang alone.[9] In the Uyghur language, Xinjiang is considered more center than northwestern in orientation.[10]

Early Caucasian Inhabitants

According to J. P. Mallory and Victor H. Mair, the Chinese describe the existence of "white people with long hair" or the Bai people in the Shan Hai Jing, who lived beyond their northwestern border.[11]

The well preserved Tarim mummies with Caucasoid features, often with reddish or blond hair, today displayed at the Ürümqi Museum and dated to the 2nd millennium BC, have been found in the same area of the Tarim Basin. Various nomadic tribes, such as the Yuezhi, Saka, and Wusun were probably part of the migration of Indo-European speakers who were settled in eastern Central Asia (possibly as far as Gansu) at that time. The Ordos culture in northern China east of the Yuezhi, is another example, yet skeletal remains from the Ordos culture found have been predominantly Mongoloid. By the time the Han dynasty under Emperor Wu (r. 141-87 BC) wrestled the Western Regions of the Tarim Basin away from its previous overlords, the Xiongnu, it was inhabited by various peoples, including Indo-European Tocharians in Turfan and Kucha and Indo-Iranian Saka peoples centered around Kashgar and Khotan.[12]

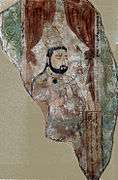

Righthand image: Two Buddhist monks on a mural of the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves near Turpan, Xinjiang, China, 9th century AD; although Albert von Le Coq (1913) assumed the blue-eyed, red-haired monk was a Tocharian,[13] modern scholarship has identified similar Caucasian figures of the same cave temple (No. 9) as ethnic Sogdians,[14] an Eastern Iranian people who inhabited Turfan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (7th-8th century) and Uyghur rule (9th-13th century).[15]

Chinese accounts

The first reference to the nomadic Yuezhi was in 645 BC by Guan Zhong in his Guanzi 管子 (Guanzi Essays: 73: 78: 80: 81). He described the Yuzhi 禺氏, or Niuzhi 牛氏, as a people from the north-west who supplied jade to the Chinese from the nearby mountains of Yuzhi 禺氏 at Gansu.[16] The supply of jade from the Tarim Basin[17] from ancient times is well documented archaeologically: "It is well known that ancient Chinese rulers had a strong attachment to jade. All of the jade items excavated from the tomb of Fuhao of the Shang dynasty by Zheng Zhenxiang, more than 750 pieces, were from Khotan in modern Xinjiang. As early as the mid-first millennium BC the Yuezhi engaged in the jade trade, of which the major consumers were the rulers of agricultural China." (Liu (2001), pp. 267–268).

The nomadic tribes of the Yuezhi are documented in Chinese historical accounts, in particular the 2nd-1st century BC "Records of the Great Historian", or Shiji, by Sima Qian. According to these accounts:

- "The Yuezhi originally lived in the area between the Qilian or Heavenly Mountains (Tian Shan) and Dunhuang, but after they were defeated by the Xiongnu they moved far away to the west, beyond Dayuan, where they attacked and conquered the people of Daxia and set up the court of their king on the northern bank of the Gui [= Oxus] River. A small number of their people who were unable to make the journey west sought refuge among the Qiang barbarians in the Southern Mountains, where they are known as the Lesser Yuezhi."[18]

According to Han accounts, the Yuezhi "were flourishing" during the time of the first great Chinese Qin emperor, but were regularly in conflict with the neighbouring tribe of the Xiongnu to the northeast.

Roman accounts

Pliny the Elder, Chap XXIV "Taprobane") reports a curious description of the Seres (in the territories of northwestern China) made by an embassy from Taprobane (Ceylon) to Emperor Claudius, saying that they "exceeded the ordinary human height, had flaxen hair, and blue eyes, and made an uncouth sort of noise by way of talking", suggesting they may be referring to the ancient Caucasian populations of the Tarim Basin.

Genetic evidence

Modern genetic analysis suggests that aboriginal inhabitants had a high proportion of DNA of European origin.[19]

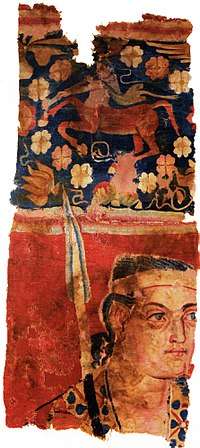

At the cemetery in Sampul (山普拉), ~14 km (8.7 mi) from the archaeological site of Khotan in Lop County, Xinjiang,[20] where Hellenistic art such as the Sampul tapestry has been found (its provenance most likely from the nearby Greco-Bactrian Kingdom),[21] the local inhabitants buried their dead there from roughly 217 BC to 283 AD.[22] DNA analysis of the human remains has revealed genetic affinities to peoples from the Caucasus, specifically a maternal lineage linked to Ossetians and Iranians, as well as an Eastern-Mediterranean paternal lineage.[20][23] Seeming to confirm this link, from historical accounts it is known that Alexander the Great, who married a Sogdian woman from Bactria named Roxana,[24][25][26] encouraged his soldiers and generals to marry local women; consequentially the later kings of the Seleucid Empire and Greco-Bactrian Kingdom had a mixed Persian-Greek ethnic background.[27][28][29][30]

In 2009, the remains of individuals found at the Xiaohe Tomb complex were analyzed for Y-DNA and mtDNA markers. The study found that while Y-DNA corresponded to West Eurasian populations, the mtDNA haplotypes were an admixture of East Asian and European origin.[31] The geographic location of where this admixing took place is suggested to be somewhere in Southern Siberia before these people moved into the Tarim Basin. Xiaohe is the oldest archaeological site yielding human remains discovered in the Tarim Basin to date.

Some Uyghur scholars claim modern Uyghurs descent from both the Turkic Uyghurs and the pre-Turkic Tocharians (Yuezhi), and relatively fair hair and eyes, as well as other so-called 'Caucasoid' physical traits, are not uncommon among Uyghurs. Genetic analyses suggest West Eurasian ("Caucasoid") maternal contribution to Uyghurs is 42.6% and the paternal between 43.9% and 61.2%. The estimation of European component in modern Uyghur population ranged from 30 to 60%.[32]

Struggle between Han dynasty and Xiongnu

.png)

.svg.png)

Traversed by the Northern Silk Road,[33] Western Regions is the Chinese name for the Tarim and Dzungaria regions of what is now northwest China. At the beginning of the Han dynasty (206 BC - AD 220), the region was subservient to the Xiongnu, a powerful nomadic people based in modern Mongolia. In the 2nd century BC, The Han Dynasty made preparations for war when the Emperor Wu of Han dispatched the explorer Zhang Qian to explore the mysterious kingdoms to the west and to form an alliance with the Yuezhi people in order to combat the Xiongnu. As a result of these battles, the Chinese controlled the strategic region from the Ordos and Gansu corridor to Lop Nor. They succeeded in separating the Xiongnu from the Qiang peoples to the south, and also gained direct access to the Western Regions. Han China sent Zhang Qian as an envoy to the states in the region, beginning several decades of struggle between the Xiongnu and Han China over dominance of the region, eventually ending in Chinese success. In 60 BC Han China established the Protectorate of the Western Regions (西域都護府) at Wulei (烏壘; near modern Luntai) to oversee the entire region as far west as the Pamir. This became the first sign of Han Chinese rule in Central Asia, the sovereignty of Han dynasty expanded into Central Asia. Tarim Basin and Indo-European kingdoms was under the control of Han dynasty and was influenced by Han Chinese emperors.

During the usurpation of Wang Mang in China, the dependent states of the protectorate rebelled and returned to Xiongnu domination in AD 13. Over the next century, Han China conducted several expeditions into the region, re-establishing the protectorate from 74-76, 91-107, and from 123 onward. After the fall of the Han dynasty (220), the protectorate continued to be maintained by Cao Wei (until 265) and the Western Jin Dynasty (from 265 onwards).

Uyghur nationalist historians such as Turghun Almas claim that Uyghurs were distinct and independent from Chinese for 6000 years, and that all non-Uyghur peoples are non-indigenous immigrants to Xinjiang.[34] However, the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) established military colonies (tuntian) and commanderies (duhufu) to control Xinjiang from 120 BCE, while the Tang dynasty (618-907) also controlled much of Xinjiang until the An Lushan rebellion.[35] Chinese historians refute Uyghur nationalist claims by pointing out the 2000-year history of Han settlement in Xinjiang, documenting the history of Mongol, Kazakh, Uzbek, Manchu, Hui, Xibo indigenes in Xinjiang, and by emphasizing the relatively late "westward migration" of the Huigu (equated with "Uyghur" by the PRC government) people from Mongolia the 9th century.[34] The name "Uyghur" was associated with a Buddhist people in the Tarim Basin in the 9th century, but completely disappeared by the 15th century, until it was revived by the Soviet Union in the 20th century.[36]

A succession of different kingdoms

The Western Jin Dynasty succumbed to successive waves of invasions by nomads from the north at the beginning of the 4th century. The short-lived non-Han Chinese kingdoms that ruled northwestern China one after the other, including Former Liang, Former Qin, Later Liang, and Western Liáng, all attempted to maintain the protectorate, with varying extents and degrees of success. After the final reunification of northern China under the Northern Wei empire, its protectorate controlled what is now the southeastern third of Xinjiang. Local states such as Kashgar (Shule Kingdom), Hotan (Yutian), Kucha (Guizi) and Cherchen (Qiemo) controlled the western half, while the central region around Turpan was controlled by Gaochang (later known as Qara-hoja), remnants of a Xiongnu state Northern Liang that once ruled part of what is now Gansu province in northwestern China.

Gokturk tribes

In the late 5th century the Tuyuhun and the Rouran asserted power in southern and northern Xinjiang, respectively, and the Chinese protectorate was lost again. In the 6th century the Turks began to emerge in the Altay region, subservient to the Rouran. Within a century they had defeated the Rouran and established a vast Turkic Khaganate, stretching over most of Central Asia past both the Aral Sea in the west and Lake Baikal in the east. In 583 the Gokturks split into western and eastern halves, with Xinjiang coming under the western half. In 609, China under the Sui Dynasty defeated the Tuyuhun, forced him to take refuge in Qilian mountains.

Tang dynasty and struggle with Tibetan Empire

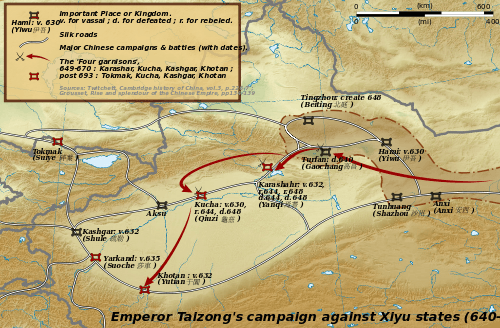

Starting from the 620's and 630's, Chinese Tang dynasty conducted a series of expeditions against the Eastern Turks.[37] By 640, military campaigns were dispatched against the Western Turkic Khaganate, and their vassals, the oasis states of southern Xinjiang.[38] The campaigns against the oasis states began under Emperor Taizong with the annexation of Gaochang in 640.[39] The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.[40]

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who dispatched an army in 657 led by Su Dingfang against the Western Turk qaghan Ashina Helu. Ashina's defeat strengthened Tang rule in southern Xinjiang and brought the regions formerly controlled by the khaganate into the Tang empire.[40] The military expedition included 10,000 horsemen supplied by the Uyghurs, who were close allies of the Tang.[40] The Uyghurs had allied with the Tang ever since the dynasty supported their revolt against the reign of the Xueyantuo, a tribe of Tiele people.[41] Xinjiang was administered through the Anxi Protectorate (安西都護府; "Protectorate Pacifying the West") and the Four Garrisons of Anxi.

Tang hegemony beyond the Pamir Mountains in modern Tajikistan and Afghanistan ended with revolts by the Turks, but the Tang retained a military presence in Xinjiang. These holdings were later invaded by the Tibetan Empire to the south, and Xinjiang alternated between Tang and Tibetan rule as they competed for control of Central Asia.[42] In 662 a rebellion broke out and Tang army was sent to control the situation, but was badly defeated by the Tibetans in the south of Kashgar. After defeating Tang in 670, the Tibetans gained control of the whole region and completely subjugated Kashgar in 676-8 and retained possession until 692, then China regained control of all southern Xinjiang, and retained it for the next fifty years. 728, the local king of Kashgar was awarded a brevet by the Tang emperor. During the devastating Anshi Rebellion, Tibetans invaded Tang China on a wide front from Xinjiang to Yunnan, sacking the Tang capital in 763, and taking control of southern Xinjiang.

A significant milestone of the Tang period of Xinjiang was that it marked the end of Indo-European influence in Xinjiang.[39] This was partially spurred by Chinese policies, which unintentionally sped the turkification of Xinjiang,[42] rather than the sinification that had occurred in other territories conquered by the Tang.[43] The Tang dynasty recruited a large number of Turkic soldiers and generals, and the Chinese garrisons of Xinjiang were for the most part staffed by Turks rather than those of the Han ethnicity. Xinjiang was beginning its transition into a region that is linguistically and culturally Turko-Mongolic, which it still is to this day.[42]

Tang dynasty and Uyghur Khanate

By 745 the Uyghur Khanate stretched from the Caspian Sea to present-day Mongolia and lasted from 745 to 840. After the Battle of Talas in 751, Uyghur Khanate took control of northern Xinjiang, as well as much of Central Asia, including Outer Mongolia, where their empire originated. It was also during this time that Tang China started a process of withdrawal from Central Asia. Bayanchur Khan acted quickly and took over the fertile Tarim Basin as well[44] at about the same time that the Tibetan Empire extended to Xinjiang.

The Chinese defeat at the Battle of Talas combined with a series of rebellions, the largest being of An Lushan, forced the Chinese emperor to turn to Bayanchur Khan for assistance. Seeing this as an ideal opportunity to meddle in Chinese affairs, the Khagan agreed, quelling several rebellions and defeating an invading Tibetan army from the south. As a result, the Uyghurs received tribute from the Chinese and Bayanchur Khan was given the daughter of the Chinese Emperor to marry (princess Ningo).

In 762, in alliance with the Tang, Tengri Bögü (Chinese transcription Idigan) launched a campaign against the Tibetans. He recaptured for the Tang Emperor the western capital Luoyang. Khagan Tengri Bögü met with Manichaean priests from Iran while on campaign, and was converted to Manicheism, adopting it as the official religion of the Uyghur Empire.

In 779 Tengri Bögü, incited by sogdian traders, living in Ordu Baliq, planned an invasion of China to take advantage of the accession of a new emperor. Tengri Bögü's uncle, Tun Bagha Tarkhan opposed this plan, fearing it would result in Uyghur complete assimilation into Han-Chinese culture.

In 840, the Kyrgyz tribe invaded from the north with a force of around 80,000 horsemen. They sacked the Uyghur capital at Ordu Baliq, razing it to the ground. The Kyrgyz captured the Uyghur Khagan, Kürebir (Hesa) and promptly beheaded him. The Kyrgyz went on to destroy other Uyghur cities throughout their empire, burning them to the ground. The last legitimate khagan, Öge, was assassinated in 847, having spent his 6-year reign in fighting the Kyrgyz and the supporters of his rival Ormïzt, a brother of Kürebir. The Kyrgyz invasion destroyed the Uyghur Empire, causing a diaspora of Uyghur people across Central Asia.

Uyghur Khanate and Kara-Khanid Khanate

Both Tibet and the Uyghur Khanate declined in the mid-9th century. After the Uyghur Khanate in Mongolia had been smashed by the Kirghiz in 840, branches of the Uyghurs established themselves in Qocha (Karakhoja) and Beshbalik near today's Turfan and Urumchi. This Uyghur Kara-Khoja Kingdom would remain in eastern Xinjiang until the 14th century, though it would be subject to various overlords during that time.

The Kara-Khanid Khanate arose some time in the ninth century from a confederation of Turkic tribes living in Semirechye, Western Tian Shan (modern Kyrgyzstan), and Western Xinjiang (Kashgaria).[45] They later occupied Transoxania. The Karakhanids were made up mainly of the Karluks, Chigils and Yaghma tribes. The capital of Karakhanid Khanate was Balasaghun on the Chu River, later also Samarkand and Kashgar. The Kara-Khanids converted to Islam, whereas the Uyghur state in eastern Xinjiang remained Manicheaean, but later converted to Buddhism. Nestorian Christianity was also a prominent faith in their kingdom. The Turkic Muslim Karakhanid Khanate attacked and conquered the Buddhist Saka Kingdom of Khotan.

Islamicisation and Turkicisation of Xinjiang

| Turkification of the Tarim Basin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

| Caucasian Indo-European Buddhist Tocharians and Eastern Iranian Sakas (Kingdom of Khotan) | Mongoloid Turkic Buddhist Uyghurs (Kingdom of Qocho) | Mongoloid Turkic Muslim Karluks (Kara-Khanid Khanate) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Satok Bughra Khan Ali Arslan Musa Yusuf Qadir Khan | ||||||||

The historical area of what is modern day Xinjiang consisted of the distinct areas of the Tarim Basin and Dzungaria, and was originally populated by Indo-European Tocharian and Iranic Saka peoples who practiced the Buddhist religion. The area was subjected to Turkification and Islamification at the hands of invading Turkic Muslims.

Buddhist Uyghur migration into the Tarim Basin

The discovery of the Tarim mummies has created a stir in the Turkic-speaking Uighur population of the region, who claim the area has always belonged to their culture, while it was not until the 10th century when the Uighurs are said by scholars to have moved to the region from Central Asia.[46] American Sinologist Victor H. Mair claims that "the earliest mummies in the Tarim Basin were exclusively Caucasoid, or Europoid" with "east Asian migrants arriving in the eastern portions of the Tarim Basin around 3,000 years ago", while Mair also notes that it was not until 842 that the Uighur peoples settled in the area.[47]

Protected by the Taklamakan Desert from steppe nomads, elements of Tocharian culture survived until the 7th century, when the arrival of Turkic immigrants from the collapsing Uyghur Khaganate of modern-day Mongolia began to absorb the Tocharians to form the modern-day Uyghur ethnic group.[47]

Mongoloid DNA

The modern Uyghurs are now a mixed hybrid of Mongoloid (East Asian) and Caucasian.[48][49][50]

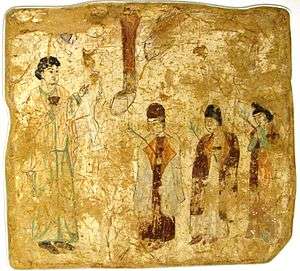

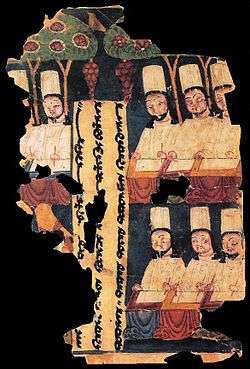

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Uyghurs

Professor James A. Millward described the original Uyghurs as physically Mongoloid, giving as an example the images in Bezeklik at temple 9 of the Uyghur patrons, until they began to mix with the Tarim Basin's original eastern Iranian inhabitants.[51]

Images of Buddhist and Manichean Turkic Uyghurs from the Bezeklik caves and Mogao grottoes. Buddhist murals at the Bezeklik Thousand Buddha Caves were damaged by local Muslim population whose religion proscribed figurative images of sentient beings, the eyes and mouths in particular were often gouged out. Pieces of murals were also broken off for use as fertilizer by the locals.[52]

Turkic-Islamic Kara-Khanid conquest of Iranic Saka Buddhist Khotan

The Islamic attacks and conquest of the Buddhist cities east of Kashgar was started by the Turkic Karakhanid Satok Bughra Khan who in 966 converted to Islam and many tales emerged about the Karakhanid ruling family's war against the Buddhists, Satok Bughra Khan's nephew or grandson Ali Arslan was slain by the Buddhists during the war. Buddhism lost territory to Islam during the Karakhanid reign around the Kashgar area.[53] A long war ensued between Islamic Kashgar and Buddhist Khotan which eventually ended in the conquest of Khotan by Kashgar.[54]

Iranic Saka peoples originally inhabited Yarkand and Kashgar in ancient times. The Buddhist Iranic Saka Kingdom of Khotan was the only city-state that was not conquered yet by the Turkic Uyghur (Buddhist) and the Turkic Qarakhanid (Muslim) states and its ruling family used Indian names and the population were devout Buddhists. The Buddhist entitites of Dunhuang and Khotan had a tight-knit partnership, with intermarriage between Dunhuang and Khotan's rulers and Dunhuang's Mogao grottos and Buddhist temples being funded and sponsored by the Khotan royals, whose likenesses were drawn in the Mogao grottoes.[55] The rulers of Khotan were aware of the menace they faced since they arranged for the Mogao grottoes to paint a growing number of divine figures along with themselves. Halfway in the 10th century Khotan came under attack by the Qarakhanid ruler Musa, and in what proved to be a pivotal moment in the Turkification and Islamification of the Tarim Basin, the Karakhanid leader Yusuf Qadir Khan conquered Khotan around 1006.[55]

The Taẕkirah is a genre of literature written about Sufi Muslim saints in Altishahr. Written sometime in the period from 1700-1849, the Eastern Turkic language (modern Uyghur) Taẕkirah of the Four Sacrificed Imams provides an account of the Muslim Karakhanid war against the Khotanese Buddhists, containing a story about Imams, from Mada'in city (possibly in modern-day Iraq) came 4 Imams who travelled to help the Islamic conquest of Khotan, Yarkand, and Kashgar by Yusuf Qadir Khan, the Qarakhanid leader.[56] Accounts of the battles waged by the invading Muslims upon the indigenous Buddhists takes up most of the Taẕkirah with descriptions such as "blood flows like the Oxus", "heads litter the battlefield like stones" being used to describe the murderous battles over the years until the "infidels" were defeated and driven towards Khotan by Yusuf Qadir Khan and the four Imams, but the Imams were assassinated by the Buddhists prior to the last Muslim victory so Yusuf Qadir Khan assigned Khizr Baba, who was born in Khotan but whose mother originated from western Turkestan's Mawarannahr, to take care of the shrine of the 4 Imams at their tomb and after Yusuf Qadir Khan's conquest of new land in Altishahr towards the east, he adopted the title "King of the East and China".[56] Due to the Imams deaths in battle and burial in Khotan, Altishahr, despite their foreign origins, they are viewed as local saints by the current Muslim population in the region.[56]

Muslim works such as Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam contained anti-Buddhist rhetoric and polemic against Buddhist Khotan,[57] aimed at "dehumanizing" the Khotanese Buddhists, and the Muslims Kara-Khanids conquered Khotan just 26 years following the completion of Ḥudūd al-ʿĀlam.[58]

Muslims gouged the eyes of Buddhist murals along Silk Road caves and Kashgari recorded in his Turkic dictionary an anti-Buddhist poem/folk song.[59]

Satuq Bughra Khan and his son directed endeavors to proselytize Islam among the Turks and engage in military conquests.[60] The Islamic conquest of Khotan led to alarm in the east and Dunhuang's Cave 17, which contained Khotanese literary works, was closed shut possibly after its caretakers heard that Khotan's Buddhist buildings were razed by the Muslims, the Buddhist religion had suddenly ceased to exist in Khotan.[61]

In 1006, the Muslim Kara-Khanid ruler Yusuf Kadir (Qadir) Khan of Kashgar conquered Khotan, ending Khotan's existence as an independent state. The war was described as a Muslim Jihad (holy war) by the Japanese Professor Takao Moriyasu. The Karakhanid Turkic Muslim writer Mahmud al-Kashgari recorded a short Turkic language poem about the conquest:

English translation:

We came down on them like a flood,

We went out among their cities,

We tore down the idol-temples,

We shat on the Buddha's head!

In Turkic:

kälginläyü aqtïmïz

kändlär üzä čïqtïmïz

furxan ävin yïqtïmïz

burxan üzä sïčtïmïz

Idols of "infidels" were subjected to desecration by being defecated upon by Muslims when the "infidel" country was conquered by the Muslims, according to Muslim tradition (it is not Muslim tradition).[64]

Maps of the Turkicisation of Xinjiang

Turkic ultra-nationalist revisionism

Some Uyghur ultra-nationalist revisionists, worried at the prospect that they are descendants of migrants into Xinjiang and could be seen as invaders and not the indigenous inhabitants, have sought to revise history like Turghun Almas in his book Uyghurlar, claiming that Turkic Uyghurs were always natives of Xinjiang, claiming that the Tocharian Tarim mummies were Uyghurs, claiming Uyghurs invented gunpowder, paper, compass, printing, and that Uyghur civilization is 6,000 years old and is the origin of all world civilization.[65][66]

The claims of these "Uyghur nationalist historians", which the majority of Uyghurs believe in, are not backed up by actual evidence.[67][68] The belief that they were native to the Tarim Basin is held by most Uyghurs.[69]

Qurban Wäli is another ultra-nationalist Uyghur who engaged in historical revisionism and claimed Uyghur civilization is 6,000 years old and native to Xinjiang.[70]

The Chinese government pointed out that it was in the 9th century when Uyghurs migrated into Xinjiang,[71][72] but since many Uyghurs believe in the opposite of whatever the Chinese government says, they eagerly believe books written by Uyghur authors which glorify their past and assume what authors like Almas write is automatically true.[73]

Historians say that it was in the 9th century when Uyghurs moved into Xinjiang.[74][75]

Legacy of Han and Tang Chinese rule in Xinjiang

Coins with both Chinese and Karoshthi inscriptions have been found in the southern Tarim Basin.[76]

It was the An Lushan Rebellion and not the defeat at Talas that ended the Tang Chinese presence in Central Asia and forced them to withdraw from Xinjiang- the significance of Talas was overblown, because the Arabs did not proceed any further after the battle.[77] Because the Arabs did not proceed to Xinjiang at all, the battle was of no importance strategically, it was An Lushan's rebellion which ended up forcing the Tang Chinese out of Central Asia.[78] Despite the conversion of some Karluk Turks after the Battle of Talas, the majority of Karluks did not convert to Islam until the mid 10th century under Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan when they established the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[79][80][81][82][83][84] This was long after the Tang dynasty was gone from Central Asia.

The military victories of the Tang in the western regions and Central Asia have been offered as explanations as to why western peoples referred to China by the name "House of Tang" (Tangjia) and another theory was suggested that China was called "Han" because of the Han dynasty military victories against peoples in the north, and the Turkic word for China, "Tamghaj" has been possibly derived from Tangjia instead of Tabgatch (Tuoba).[85]

In the Chu valley in Central Asia Tang dynasty era Chinese coins continued to be copied and minted after the Chinese left the area.[86]

An indelible impression was left on eastern Xinjiang's administration and culture in Turfan by the Chinese Tang rule which consisted of settlements, and military farms in addition to the spread of Chinese influence such as the sancai three colour glaze in Central Asia and Western Eurasia, in Xinjiang there was continued circulation of Chinese coins.[87]

Turkic Empires after the Tang gained prestige by connecting themselves with north Chinese states with the Qara-Khitay and Qara-Khanid khans using the title of "Chinese emperor", Khitay was used by the Qara-Khitay and Tabghach was used by the Qarakhanids.[88] The entry into the previously Indo-European Soghdian and Tokharian speaking Central Eurasia and Xinjiang of tribes of Turkic speaking origin and the started of Turkicisation originate in the 7th century with the disintegration of the Turkic Khaganate, resulting in Eurasia being populated by many peoples who consider themselves Turks.

Two different branches, the junior Bughra (bull camel) and the Arslan (lion) formed the Qarakhanid royal family. The title "Khan of China" (Tamghaj Khan) (تمغاج خان) was used by the Qarakhanid rulers.[89] The Qarakhanids were the ones who are responsible for the modern Uyghur population being Muslim and the Qarakhanids were converted when Satuq Bughra Khan converted to Islam after contacts with the Muslim Samanids.

Bughra Khan was overthrown by his nephew Satuq when Satuq converted to Islam, the Arslan Khans were also toppled and Balasaghun taken by Satuq, with the conversion of the Qarakhanid Turk population to Islam following Satuq's accession to power and the spread of Islam among the Qarakhanid Turks led to the conquest of Transoxiana and the Samanids by the Qarakhanids and the Qarakhanids were the people who bequeathed the Islamic religion to the modern Uyghurs while the modern Uyghurs adopted the modern name of their ethnic group from the Uyghur Qocho Kingdom and Uyghur Empire.[90]

The Turkic Qarakhanid and Uyghur Qocho Kingdoms were both states founded by invaders while the native populations of the region were Iranic and Tocharian peoples along with some Chinese in Qocho and Indians, who married and mixed with the Turkic invaders, and prominent Qarakhanid people such as Mahmud Kashghari hold a high position among modern Uyghurs.[91]

Kashghari viewed the least Persian mixed Turkic dialects as the "purest" and "the most elegant".[92]

Persian, Arab and other western Asian writers called China by the name "Tamghaj".[93]

The Qarakhanid ruler of Kashgar was called Tamghaj Khan, while the Khitan ruler was called the Khan of Chīn, some Khitans migrated into western areas like the Qarakhanid state even before the establishment of the Kara-Khitan state.[94]

During the Liao dynasty Han Chinese lived in Kedun, situated in present-day Mongolia.[95]

In 1124 the migration of the Khitan under Yelü Dashi included a big part of the Kedun population, which consisted of Han Chinese, Bohai, Jurchen, Mongol tribes, Khitan, in addition to the Xiao consort clan and the Yelü royal family on the march to establish the Qara-Khitan.[96]

The Khitan Qara-Khitai empire in Central Asia kept Chinese characteristics in their state since the Chinese characteristics appealed to the Muslim Central Asians and helped validate Qara Khita rule over them, despite the fact that Han Chinese were to be found among the population of the Qara Khitan because it was comparatively small so it is clear that the Chinese characteristics were not kept to appease them, the Mongols later moved more Han Chinese into Besh Baliq, Almaliq and Samarqand in Central Asia to work as aristans and farmers.[97]

The Qara Khitai used the "image of China" to legitimize their ruler to the Central Asian Muslims since China had a good reputation at the time among Central Asian Muslims before the Mongol invasions, it was viewed as extremely civilized, known for its unique script, its expert artisans were well known, justice and religious tolerance were among the virtues attributed to Chinese despite their idol worship and the Turk, Arab, Byzantium, Indian rulers, and the Chinese emperor were known as the world's "five great kings", the memory of Tang China was engraved into the Muslim perception so their continued to view China through the lens of the Tang dynasty and anachronisms appeared in Muslim writings due to this even after the end of the Tang, China was known as chīn (چين) in Persian and as ṣīn (صين) in Arabic while the Tang dynasty capital Changan was known as Ḥumdān (حمدان).[98]

Muslim Muslim writers like Marwazī and Mahmud Kashghārī had more up to date information about China in their writings, Kashgari viewed Kashgar as part of China. Ṣīn [i.e., China] is originally three fold; Upper, in the east which is called Tawjāch; middle which is Khitāy, lower which is Barkhān in the vicinity of Kashgar. But know Tawjāch is known as Maṣīn and Khitai as Ṣīn" China was called after the Toba rulers of the Northern Wei by the Turks, pronounced by them as Tamghāj, Tabghāj, Tafghāj or Tawjāch. India introduced the name Maha Chin (greater China) which caused the two different names for China in Persian as chīn and māchīn (چين ماچين) and Arabic ṣīn and māṣīn (صين ماصين), Southern China at Canton was known as Chin while Northern China's Changan was known as Machin, but the definition switched and the south was referred to as Machin and the north as Chin after the Tang dynasty, Tang China had controlled Kashgar since of the Tang's Anxi protectorate's "Four Garrisons" seats, Kashgar was among them, and this was what led writers like Kashghārī to place Kashgar within the definition of China, Ṣīn, whose emperor was titled as Tafghāj or Tamghāj, Yugur (yellow Uighurs or Western Yugur) and Khitai or Qitai were all classified as "China" by Marwazī while he wrote that Ṣīnwas bordered by placed SNQU and Maṣīn.[99] Machin, Mahachin, Chin, and Sin were all names of China.[100]

Muslim writers like Marwazī wrote that Transoxania was a former part of China, retaining the legacy of Tang Chinese rule over Transoxania in Muslim writings, In ancient times all the districts of Transoxania had belonged to the kingdom of China [Ṣīn], with the district of Samarqand as its centre. When Islam appeared and God delivered the said district to the Muslims, the Chinese migrated to their [original] centers, but there remained in Samarqand, as a vestige of them, the art of making paper of high quality. And when they migrated to Eastern parts their lands became disjoined and their provinces divided, and there was a king in China and a king in Qitai and a king in Yugur., Muslim writers viewed the Khitai, the Gansu Uighur Kingdom and Kashgar as all part of "China" culturally and geographically with the Muslim Central Asians retaining the legacy of Chinese rule in Central Asia by using titles such as "Khan of China" (تمغاج خان) (Tamghaj Khan or Tawgach) in Turkic and "the King of the East in China" (ملك المشرق (أو الشرق) والصين) (malik al-mashriq (or al-sharq) wa'l-ṣīn) in Arabic which were titles of the Muslim Qarakhanid rulers and their Qarluq ancestors.[101][102]

The title Malik al-Mashriq wa'l-Ṣīn was bestowed by the 'Abbāsid Caliph upon the Tamghaj Khan, the Samarqand Khaqan Yūsuf b. Ḥasan and after that coins and literature had the title Tamghaj Khan appear on them and were continued to be used by the Qarakhanids and the Transoxania-based Western Qarakhanids and some Eastern Qarakhanid monarchs, so therefore the Kara-Khitan (Western Liao)'s usage of Chinese things such as Chinese coins, the Chinese writing system, tablets, seals, Chinese art products like porcelein, mirrors, jade and other Chinese customs were designed to appearl to the local Central Asian Muslim population since the Muslims in the area regarded Central Asia as former Chinese territories and viewed links with China as prestigious and Western Liao's rule over Muslim Central Asia caused the view that Central Asia was a Chinese territory to reinforce upon the Muslims; "Turkestan" and Chīn (China) were identified with each other by Fakhr al-Dīn Mubārak Shāh with China being identified as the country where the cities of Balāsāghūn and Kashghar were located.[103]

The Liao Chinese traditions and the Qara Khitai's clinging helped the Qara Khitai avoid Islamization and conversion to Islam, the Qara Khitai used Chinese and Inner Asian features in their administrative system.[104]

Muslim writers wrote that "Tamghājī silver coins" (sawmhā-yi ṭamghājī) were present in Balkh while tafghājī was used by the writer Ḥabībī, the Qarakhānid leader Böri Tigin (Ibrāhīm Tamghāj Khān) was possibly the one who minted the coins.[105]

The relationship to China was used by the Qara-Khanids to enhace their standing since Central Asian Muslims associated prestige and grandeur with China so the Arabic title "the king of the East and China" (malek al-mašreq wa'l-Ṣin) and the Turkic title "Khan of China" Ṭamḡāj Khan was extensively employed by Khans of the Qara-khanids.[106]

Although in modern Urdu Chin means China, Chin referred to Central Asia in Muhammad Iqbal's time, which is why Iqbal wrote that "Chin is ours" (referring to the Muslims) in his song Tarana-e-Milli.[107]

Aladdin, an Arabic Islamic story which is set in China, may have been referring to Central Asia.[108]

In the Persian epic Shahnameh the Chin and Turkestan are regarded as the eame, the Khan of Turkestan is called the Khan of Chin.[109][110][111]

The Tang Chinese reign over Qocho and Turfan and the Buddhist religion left a lasting legacy upon the Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho with the Tang presented names remaining on the more than 50 Buddhist temples with Emperor Tang Taizong's edicts stored in the "Imperial Writings Tower " and Chinese dictionaries like Jingyun, Yuian, Tang yun, and da zang jing (Buddhist scriptures) stored inside the Buddhist temples and Persian monks also maintained a Manichaean temple in the Kingdom., the Persian Hudud al-'Alam uses the name "Chinese town" to called Qocho, the capital of the Uyghur kingdom.[112]

The Turfan Buddhist Uighurs of the Kingdom of Qocho continued to produce the Chinese Qieyun rime dictionary and developed their own pronunciations of Chinese characters, left over from the Tang influence over the area.[113]

The modern Uyghur linguist Abdurishid Yakup pointed out that the Turfan Uyghur Buddhists studied the Chinese language and used Chinese books like Qianziwen (the thousand character classic) and Qieyun *(a rime dictionary) and it was written that "In Qocho city were more than fifty monasteries, all titles of which are granted by the emperors of the Tang dynasty, which keep many Buddhist exts as Tripitaka, Tangyun, Yupuan, Jingyin etc." [114]

In Central Asia the Uighurs viewed the Chinese script as "very prestigious" so when they developed the Old Uyghur alphabet, based on the Syriac script, they deliberately switched it to vertical like Chinese writing from its original horizontal position in Syriac.[115]

Qara Khitai

In 1132, remnants of the Liao dynasty from Manchuria and North China entered Xinjiang, fleeing the onslaught of the Jurchens into North China. They established an exile regime, the Qara Khitai, which became overlord over both Kara-Khanid-held and Uyghur State-held parts of the Tarim Basin for the next century. In 1208, a Naiman prince named Kuchlug fled his homeland after being defeated by the Mongols. He fled westward to the Qara Khitai, where he became an advisor. However, he rebelled three years later and usurped the throne of Qara Khitai. His regime proved to be short-lived however because the Mongols under Genghis Khan would soon invade Central Asia including the Qara Khitai.

Mongol Empire, Yuan dynasty and Chagatai Khanate

After Genghis Khan had unified the Mongols and began his advance west, the Uyghur state in the Turfan-Urumchi area offered its allegiance to the Mongol Empire in 1209, contributing taxes and troops to the Mongol imperial effort and worked as civil servants to the Mongols. In return, the Uyghur rulers retained control of their kingdom. In 1218, Genghis Khan's Mongol Empire captured what was once Qara Khitai's territories. After the break-up of the Mongol Empire into smaller khanates, most of modern-day Xinjiang was briefly controlled by the Yuan dynasty founded by Kublai Khan, the eastern division of the Mongol Empire based in modern-day Beijing. However, during the Kaidu–Kublai war fought between the Yuan and the Chagatai Khanate based in Central Asia under the leadership of Kaidu, most of Xinjiang was occupied by the Chagatai Khanate. This would last until the mid-14th century, when the Chagatai Khanate was divided into two.

Moghulistan

After the death of Qazan Khan in 1346, the Chagatai Khanate, which embraced both East and West Turkestan, was divided into western (Transoxiana) and eastern (Moghulistan) halves. Power in the western half devolved into the hands of several tribal leaders, most notably the Qara'unas. Khans appointed by the tribal rulers were mere puppets. In the east, Tughlugh Timur (1347–1363), an obscure Chaghataite adventurer, gained ascendancy over the nomadic Mongols, and converted to Islam. During his rein (and ruled until 1363), the moghuls were converted to Islam and slowly turkizised. In 1360, and again in 1361, he invaded the western half in the hope that he could reunify the khanate. At their height, the Chaghataite domains extended from the Irtysh River in Siberia down to Ghazni in Afghanistan, and from Transoxiana to the Tarim Basin.

Moghulistan embraced settled lands in Eastern Turkestan as well as nomad lands north of Tengri tagh. The settled lands were known at the time as Manglai Sobe or Mangalai Suyah, which translates as Shiny Land, or Advanced Land Which Faced the Sun. These lands included west and central Tarim oasis-cities, such as Khotan, Yarkand, Yangihisar, Kashgar, Aksu, and Uch Turpan; and hardly involved eastern Tangri Tagh oasis-cities, such as Kucha, Karashahr, Turpan and Kumul, where a local uyghur administration and buddhist population still existed. The nomadic areas comprised the present Kyrghyzstan and part of Kazakhstan, including Jettisu, the area of seven rivers.

Moghulistan existed around 100 years, and then split into two parts: Yarkand state (mamlakati Yarkand), with its capital at Yarkand, which embraced all the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan, and nomad Moghulistan, which embraced the nomad lands north of Tengri Tagh. The founder of Yarkand was Mirza Abu-Bakr, who was from the dughlat tribe. In 1465, he raised a rebellion, captured Yarkand, Kashgar, and Khotan, and declared himself an independent ruler, successfully repelling attacks by the Moghulistan rulers Yunus Khan and his son Akhmad Khan, or Ahmad Alaq, named Alach, "Slaughterer", for his war against the kalmyks.

Dughlat amirs had ruled the country that lay south of the Tarim Basin from the middle of the thirteenth century, on behalf of Chagatai Khan and his descendents, as their satellites. The first dughlat ruler, who received lands directly from the hands of Chagatai, was amir Babdagan or Tarkhan. The capital of the emirate was Kashgar, and the country was known as Mamlakati Kashgar. Although the emirate, representing the settled lands of Eastern Turkestan, was formally under the rule of the moghul khans, the dughlat amirs often tried to put an end to that dependence, and raised frequent rebellions, one of which resulted in the separation of Kashgar from Moghulistan for almost 15 years (1416–1435). Mirza Abu-Bakr ruled Yarkand for 48 years.[116]

Islamic conquest of the Buddhist Uighurs

| Islamification of the Tarim Basin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Turkic Muslim Chagatai Khanate | Turkic Buddhist Uyghurs (Kingdom of Qocho and Qara Del) | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Khizr Khwaja Mansur | |||||||

Buddhism survived in Uyghurstan (Turfan and Qocho). during the Ming dynasty.[117]

The Buddhist Uyghurs of the Kingdom of Qocho and Turfan were converted to Islam by conquest during a ghazat (holy war) at the hands of the Muslim Chagatai Khizr Khwaja.[118]

Kara Del was a Mongolian ruled and Uighur populated Buddhist Kingdom. The Muslim Chagatai Khan Mansur invaded and used the sword to make the population convert to Islam.[119]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[120][121]

According to Joseph Fletcher, For centuries Altishar had been 'the abod of Islam'. Its inhabitants lived under the obligation of Jihad.[122]

Maps of the Islamicisation of Xinjiang

State of Yarkand

In May, 1514, Sultan Said Khan, grandson of Yunus Khan (ruler of Moghulistan between 1462 and 1487) and third son of Ahmad Alaq, made an expedition against Kashgar from Andijan with only 5000 men, and having captured the Yangi Hissar citadel, that defended Kashgar from south road, took the city, dethroning Mirza Abu-Bakr. Soon after, other cities of Eastern Turkestan — Yarkant, Khotan, Aksu, and Uch Turpan — joined him, and recognized Sultan Said Khan as ruler, creating a union of six cities, called Altishahr. Sultan Said Khan's sudden success is considered to be contributed to by the dissatisfaction of the population with the tyrannical rule of Mirza Abu-Bakr and the unwillingness of the dughlat amirs to fight against a descendant of Chagatai Khan, deciding instead to bring the head of the slain ruler to Sultan Said Khan. This move put an end to almost 300 years of rule (nominal and actual) by the Dughlat Amirs in the cities of West Kashgaria (1219–1514). He made Yarkand the capital of a state, "Mamlakati Yarkand" which lasted until 1678.

The Khojah Kingdom

In the 17th century, the Dzungars (Oirats, Kalmyks) established an empire over much of the region. Oirats controlled an area known as Grand Tartary or the Kalmyk Empire to Westerners, which stretched from the Great Wall of China to the Don River, and from the Himalayas to Siberia. A Sufi master Khoja Āfāq defeated Saidiye kingdom and took the throne at Kashgar with the help of the Oirat (Dzungar) Mongols. After Āfāq's death, the Dzungars held his descendants hostage. The Khoja dynasty rule in the Altishahr (Tarim Basin) region lasted until 1759.

Dzungar Khanate

The Mongolian Dzungar (also Zunghar; Mongolian: Зүүнгар Züüngar) was the collective identity of several Oirat tribes that formed and maintained one of the last nomadic empires. The Dzungar Khanate covered the area called Dzungaria and stretched from the west end of the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan, and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia. Most of this area was only renamed "Xinjiang" by the Chinese after the fall of the Dzungar Empire. It existed from the early 17th century to the mid-18th century.

The Turkic Muslim sedentary people of the Tarim Basin were originally ruled by the Chagatai Khanate while the nomadic Buddhist Oirat Mongol in Dzungaria ruled over the Dzungar Khanate. The Naqshbandi Sufi Khojas, descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, had replaced the Chagatayid Khans as the ruling authority of the Tarim Basin in the early 17th century. There was a struggle between two factions of Khojas, the Afaqi (White Mountain) faction and the Ishaqi (Black Mountain) faction. The Ishaqi defeated the Afaqi, which resulted in the Afaqi Khoja inviting the 5th Dalai Lama, the leader of the Tibetan Buddhists, to intervene on his behalf in 1677. The 5th Dalai Lama then called upon his Dzungar Buddhist followers in the Dzungar Khanate to act on this invitation. The Dzungar Khanate then conquered the Tarim Basin in 1680, setting up the Afaqi Khoja as their puppet ruler.

Khoja Afaq asked the 5th Dalai Lama when he fled to Lhasa to help his Afaqi faction take control of the Tarim Basin (Kashgaria).[123] The Dzungar leader Galdan was then asked by the Dalai Lama to restore Khoja Afaq as ruler of Kashgararia.[124] Khoja Afaq collaborated with Galdan's Dzungars when the Dzungars conquered the Tarim Basin from 1678-1680 and set up the Afaqi Khojas as puppet client rulers.[125][126][127] The Dalai Lama blessed Galdan's conquest of the Tarim Basin and Turfan Basin.[128]

67,000 patman (each patman is 4 piculs and 5 pecks) of grain 48,000 silver ounces were forced to be paid yearly by Kashgar to the Dzungars and cash was also paid by the rest of the cities to the Dzungars. Trade, milling, and distilling taxes, corvée labor,saffron, cotton, and grain were also extracted by the Dzungars from the Tarim Basin. Every harvest season, women and food had to be provided to Dzungars when they came to extract the taxes from them.[129]

When the Dzungars levied the traditional nomadic Alban poll tax upon the Muslims of Altishahr, the Muslims viewed it as the payment of jizyah (a tax traditionally taken from non-Muslims by Muslim conquerors).[130]

After being converted to Islam, the descendants of the previously Buddhist Uyghurs in Turfan failed to retain memory of their ancestral legacy and falsely believed that the "infidel Kalmuks" (Dzungars) were the ones who built Buddhist monuments in their area.[120][121]

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty, established by the Manchus in China, gained control over eastern Xinjiang as a result of a long struggle with the Dzungars that began in the seventeenth century. In 1755, the Qing Empire attacked Ghulja, and captured the Dzungar Khan. Over the next two years, the Manchus and Mongol armies of the Qing destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar Khanate, and attempted to divide the Xinjiang region into four sub-Khanates under four chiefs. Similarly, the Qing made members of a clan of Sufi shaykhs known as the Khojas, rulers in the western Tarim Basin, south of the Tianshan Mountains. After Oirat nobel Amursana's request to be declared Dzungar khan went unanswered, he led a revolt against the Qing. Over the next two years, Qing armies destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar khanate.

The Turkic Muslims of the Turfan and Kumul Oases then submitted to the Qing dynasty of China, and asked China to free them from the Dzungars. The Qing accepted the rulers of Turfan and Kumul as Qing vassals. The Qing dynasty waged war against the Dzungars for decades until finally defeating them and then Qing Manchu Bannermen carried out the Dzungar genocide, nearly wiping them from existence and depopulating Dzungaria. The Qing then freed the Afaqi Khoja leader Burhan-ud-din and his brother Khoja Jihan from their imprisonment by the Dzungars, and appointed them to rule as Qing vassals over the Tarim Basin. The Khoja brothers decided to renege on this deal and declare themselves as independent leaders of the Tarim Basin. The Qing and the Turfan leader Emin Khoja crushed their revolt and China then took full control of both Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin by 1759.

After perpetrating wholesale massacres on the native Dzungar Oirat Mongol population in the Dzungar genocide, in 1759, the Qing finally consolidated their authority by settling Chinese emigrants, together with a Manchu Qing garrison. The Qing put the whole region under the rule of a General of Ili, headquartered at the fort of Huiyuan (the so-called "Manchu Kuldja", or Yili), 30 km (19 mi)west of Ghulja (Yining). The Qing Qianlong Emperor conquered the Dzungarian plateau and the Tarim Basin, bringing the two separate regions, respectively north and south of the Tianshan mountains, under his rule as Xinjiang.[131] The south was inhabited by Turkic Muslims (Uyghurs) and the north by Dzungar Mongols.[132] The Dzungars were also called "Eleuths" or "Kalmyks".

The Qing identified their state as "China" (Zhongguo), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in Manchu. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing state (including present-day Manchuria, Dzungaria in Xinjiang, Mongolia, and other areas) as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state. The Qianlong Emperor compared his achievements with that of the Han and Tang ventures into Central Asia.[133] Qianlong's conquest of Xinjiang was driven by his mindfulness of the examples set by the Han and Tang[134] Qing scholars who wrote the official Imperial Qing gazetteer for Xinjiang made frequent references to the Han and Tang era names of the region.[135] The Qing conqueror of Xinjiang, Zhao Hui, is ranked for his achievements with the Tang dynasty General Gao Xianzhi and the Han dynasty Generals Ban Chao and Li Guangli.[136] Both aspects of the Han and Tang models for ruling Xinjiang were adopted by the Qing and the Qing system also superficially resembled that of nomadic powers like the Qara Khitay, but in reality the Qing system was different from that of the nomads, both in terms of territory conquered geographically and their centralized administrative system, resembling a western stye (European and Russian) system of rule.[137] The Qing portrayed their conquest of Xinjiang in officials works as a continuation and restoration of the Han and Tang accomplishments in the region, mentioning the previous achievements of those dynasties.[138] The Qing justified their conquest by claiming that the Han and Tang era borders were being restored,[139] and identifying the Han and Tang's grandeur and authority with the Qing.[140] Many Manchu and Mongol Qing writers who wrote about Xinjiang did so in the Chinese language, from a culturally Chinese point of view.[141] Han and Tang era stories about Xinjiang were recounted and ancient Chinese places names were reused and circulated.[142] Han and Tang era records and accounts of Xinjiang were the only writings on the region available to Qing era Chinese in the 18th century and needed to be replaced with updated accounts by the literati.[132][141]

After Qing dynasty defeated the Dzungar Oirat Mongols and exterminated them from their native land of Dzungaria in the genocide, the Qing settled Han, Hui, Manchus, Xibe, and Taranchis (Uyghurs) from the Tarim Basin, into Dzungaria. Han Chinese criminals and political exiles were exiled to Dzhungaria, such as Lin Zexu. Chinese Hui Muslims and Salar Muslims belonging to banned Sufi orders like the Jahriyya were also exiled to Dzhungaria as well. In the aftermath of the crushing of the 1781 Jahriyya rebellion, Jahriyya adherents were exiled.

Han and Hui merchants were initially only allowed to trade in the Tarim Basin, while Han and Hui settlement in the Tarim Basin was banned, until the Muhammad Yusuf Khoja invasion, in 1830 when the Qing rewarded the merchants for fighting off Khoja by allowing them to settle down.[143] Robert Michell noted that as of 1870, there were many Chinese of all occupations living in Dzungaria and they were well settled in the area, while in Turkestan (Tarim Basin) there were only a few Chinese merchants and soldiers in several garrisons among the Muslim population.[144][145] At the start of the 19th century, 40 years after the Qing reconquest, there were around 155,000 Han and Hui Chinese in northern Xinjiang and somewhat more than twice that number of Uyghurs in southern Xinjiang.[146]

Yakub Beg ruled at the height of The Great Game era when the British, Russian, and Manchu Qing empires were all vying for Central Asia. Kashgaria extended from the capital Kashgar in south-western Xinjiang to Ürümqi, Turfan, and Hami in central and eastern Xinjiang more than a thousand kilometers to the north-east, including a majority of what was known at the time as East Turkestan.[147] Kashgar and the other cities of the Tarim basin remained under Yakub Beg's rule until December 1877. Yakub Beg's rule lasted until General Zuo Zongtang (also known as General Tso) reconquered the region in 1877 for Qing China. In 1881, Qing China recovered the Gulja region through diplomatic negotiations (Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881)).

In 1884, Qing China renamed the conquered region, established Xinjiang ("new frontier") as a province, formally applying onto it the political system of China proper. The two previously separate regions, Dzungaria, known as Zhunbu (準部, Dzungar region) or Tianshan Beilu (天山北路, Northern March),[148][149][150] and the Tarim Basin, which had been known as Altishahr, Huibu (Muslim region), Huijiang (Muslim-land) or "Tianshan Nanlu" (天山南路, Southern March),[151][152] were combined into a single province called Xinjiang in 1884.[153] Before this, there was never one administrative unit in which North Xinjiang (Zhunbu) and Southern Xinjiang (Huibu) were integrated together.[154] Dzungaria's alternate name is 北疆 Beijing (North Xinjiang) and Altishahr's alternate name is 南疆 Nanjiang (South Xinjiang).[155]

After Xinjiang was converted into a province by the Qing, the provincialisation and reconstruction programs initiated by the Qing resulted in the Chinese government helping Uyghurs migrate from southern Xinjiang to other areas of the province, like the area between Qitai and the capital, which was formerly nearly completely inhabited by Han Chinese, and other areas like Urumqi, Tacheng (Tabarghatai), Yili, Jinghe, Kur Kara Usu, Ruoqiang, Lop Nor, and the Tarim River's lower reaches.[156] It was during Qing times that Uyghurs were settled throughout all of Xinjiang, from their original home cities in the western Tarim Basin.

Temporary marriage

There were eras in Xinjiang's history where intermarriage was common, "laxity" which set upon Uyghur women led them to marry Chinese men and not wear the veil in the period after Yaqub Beg's rule ended, it is also believed by Uyghurs that some Uyghurs have Han Chinese ancestry from historical intermarriage, such as those living in Turpan.[157] From 1911-1949 when the Guomindang ruled, Han soldiers were approached for relationships by a number of Uyghur girls.[158]

Although banned in Islam, a form of temporary marriage which the man could easily terminate and ignoring the traditional marriage contract was created called marriage of convenience by Turki Muslims in Xinjiang and one was conducted by the repetition of the Quran's Surah Fatiha by an Emam between Ughlug Beg's great granddaughter Nura Han and Ahmad Kamal.[159]

Even though Muslim women are forbidden to marry non-Muslims in Islamic law, from 1880-1949 it was frequently violated in Xinjiang since Chinese men married Muslim Turki (Uyghur) women, a reason suggested by foriengers that it was due to the women being poor, while the Turki women who married Chinese were labelled as whores by the Turki community, these marriages were illegitimate according to Islamic law but the women obtained benefits from marrying Chinese men since the Chinese defended them from Islamic authorities so the women were not subjected to the tax on prostitution and were able to save their income for themselves. Chinese men gave their Turki wives privileges which Turki men's wives did not have, since the wives of Chinese did not have to wear a veil and a Chinese man in Kashgar once beat a mullah who tried to force his Turki Kashgari wife to veil. The Turki women also benefited in that they were not subjected to any legal binding to their Chinese husbands so they could make their Chinese husbands provide them with as much their money as she wanted for her relatives and herself since otherwise the women could just leave, and the property of Chinese men was left to their Turki wives after they died.[160] Turki women considered Turki men to be inferior husbands to Chinese and Hindus. Because they were viewed as "impure", Islamic cemeteries banned the Turki wives of Chinese men from being buried within them, the Turki women got around this problem by giving shrines donations and buying a grave in other towns. Besides Chinese men, other men such as Hindus, Armenians, Jews, Russians, and Badakhshanis intermarried with local Turki women.[161] The local society accepted the Turki women and Chinese men's mixed offspring as their own people despite the marriages being in violation of Islamic law. Turki women also conducted temporary marriages with Chinese men such as Chinese soldiers temporarily stationed around them as soldiers for tours of duty, after which the Chinese men returned to their own cities, with the Chinese men selling their mixed daughters with the Turki women to his comrades, taking their sons with them if they could afford it but leaving them if they couldn't, and selling their temporary Turki wife to a comrade or leaving her behind.[162] The basic formalities of normal marriages were maintained as a facade even in temporary marriages.[163] Prostitution by Turki women due to the buying of daughters from impoverished families and divorced women was recorded by Scotsman George Hunter.[164] Mullahs officiated temporary marriages and both the divorce and the marriage proceedings were undertaken by the mullah at the same ceremony if the marriage was only to last for a certain arranged time and there was a temporary marriage bazaar in Yangi Hissar according to Nazaroff.[165][166] Islamic law was being violated by the temporary marriages which particularly violated Sunni Islam.[167]

Valikhanov claimed that foreigners children in Turkistan were referred to by the name çalğurt. Turki women were bashed as of being negative character by a Kashgari Turki woman's Tibetan husband- racist views of each other's ethnicities between partners in interethnic marriages still persisted sometimes. It was mostly Turki women marrying foreign men with a few cases of the opposite occurring in this era.t[168]

Andijani (Kokandi) Turkic Muslim merchants (from modern Uzbekistan), who shared the same religion, a similar culture, cuisine, clothing, and phenotypes with the Altishahri Uyghurs, frequently married local Altishahri women and the name "chalgurt" was applied to their mixed race daughters and sons, the daughters were left behind with their Uyghur Altishahri mothers while the sons were taken by the Kokandi fathers when they returned to their homeland.[169]

The Qing banned Khoqandi merchants from marrying Kashgari women. Due to 'group jealously' disputes broke out due to Chinese and Turki crossing both religious and ethnic differences and engaging and sex. Turki locals viewed fellow Turkic Muslim Andijanis also as competitors for their own women. A Turki proverb said Do not let a man from Andijan into your house.[170]

Turki women were able to inherited the property of their Chinese husbands after they died.[171]

In Xinjiang temporary marriage, marriage de convenance, called "waqitliq toy" in Turki, was one of the prevalent forms of polygamy, "the mulla who performs the ceremony arranging for the divorce at the same time", with women and men marrying for a fixed period of time for several days are a week. While temporary marriage was banned in Russian Turkestan, Chinese ruled Xinjiang permitted the temporary marriage where it was widespread.[172]

Chinese merchants and soldiers, foreigners like Russians, foreign Muslims, and other Turki merchants all engaged in temporary marriages with Turki women, since a lot of foreigners lived in Yarkand, temporary marriage flourished there more than it did towards areas with fewer foreigners like areas towards Kucha's east.[173]

Childless, married youthful women were called "chaucan" in Turkey, and Forsyth mission participant Dr. Bellew said that "there was the chaucan always ready to contract an alliance for a long or short period with the merchant or traveller visiting the country or with anybody else".[174][175] Henry Lansdell wrote in 1893 in his book Chinese Central Asia an account of temporary marriage practiced by a Turki Muslim woman, who married three different Chinese officers and a Muslim official.[176] The station of prostitutes was accorded by society to these Muslim women who had sex with Chinese men.[177]

Turkic Muslims in different areas of Xinjiang held derogatory views of each other such as claiming that Chinese men were welcomed by the loose Yamçi girls.[178]

Intermarriage and patronage of prostitutes were among the forms of interaction between the Turki in Xinjiang and visiting Chinese merchants.[179]

Many of the young Kashgari women were most attractive in appearance, and some of the little girls quite lovely, their plaits of long hair falling from under a jaunty little embroidered cap, their big dark eyes, flashing teeth and piquant olive faces reminding me of Italian or Spanish children. One most beautiful boy stands out in my memory. He was clad in a new shirt and trousers of flowered pink, his crimson velvet cap embroidered with gold, and as he smiled and salaamed to us I thought he looked like a fairy prince. The women wear their hair in two or five plaits much thickened and lengthened by the addition of yak's hair, but the children in several tiny plaits.

The peasants are fairly well off, as the soil is rich, the abundant water-supply free, and the taxation comparatively light. It was always interesting to meet them taking their live stock into market. Flocks of sheep with tiny lambs, black and white, pattered along the dusty road; here a goat followed its master like a dog, trotting behind the diminutive ass which the farmer bestrode; or boys, clad in the whity-brown native cloth, shouted incessantly at donkeys almost invisible under enormous loads of forage, or carried fowls and ducks in bunches head downwards, a sight that always made me long to come to the rescue of the luckless birds.

It was pleasant to see the women riding alone on horseback, managing their mounts to perfection. They formed a sharp contrast to their Persian sisters, who either sit behind their husbands or have their steeds led by the bridle; and instead of keeping silence in public, as is the rule for the shrouded women of Iran, these farmers' wives chaffered and haggled with the men in the bazar outside the city, transacting business with their veils thrown back.

Certainly the mullas do their best to keep the fair sex in their place, and are in the habit of beating those who show their faces in the Great Bazar. But I was told that poetic justice had lately been meted out to one of these upholders of the law of Islam, for by mistake he chastised a Kashgari woman married to a Chinaman, whereupon the irate husband set upon him with a big stick and castigated him soundly.[180][181][182][183]

Almost every Chinaman in Yarkand, soldier or civilian, takes unto himself a temporary wife, dispensing entirely with the services of the clergy, as being superfluous, and most of the high officials also give way to the same amiable weakness, their mistresses being in almost all cases natives of Khotan, which city enjoys the unenviable distinction of supplying every large city in Turkestan with courtesans.

When a Chinaman is called back to his own home in China proper, or a Chinese soldier has served his time in Turkestan and has to return to his native city of Pekin or Shanghai, he either leaves his temporary wife behind to shift for herself, or he sells her to a friend. If he has a family he takes the boys with him~—if he can afford it—failing that, the sons are left alone and unprotected to fight the battle of life, While in the case of daughters, he sells them to one of his former companions for a trifling sum.

The natives, although all Mahammadans, have a strong predilection for the Chinese, and seem to like their manners and customs, and never seem to resent this behaviour to their womankind, their own manners, customs, and morals (?) being of the very loosest description.[184][185]

That a Muslim should take in marriage one of alien faith is not objected to; it is rather deemed a meritorious act thus to bring an unbeliever to the true religion. The Muslim woman, on the other hand, must not be given in marriage to a non-Muslim; such a union is regarded as the most heinous of sins. In this matter, however, compromises are sometimes made with heaven: the marriage of a Turki princess with the emperor Ch'ien-lung has already been referred to; and, when the present writer passed through Minjol (a day's journey west of Kashgar) in 1902, a Chinese with a Turki wife (? concubine) was presented to him.[186]

He procured me a Chinese interpreter, Fong Shi, a pleasant and agreeable young Chinaman, who wrote his mother-tongue with ease and spoke Jagatai Turki fluently, and—did not smoke opium. He left his wife and child behind him in Khotan, Liu Darin making himself answerable for their maintenance. But I also paid Fong Shi three months' salary in advance, and that money he gave to his wife. Whenever I could find leisure he was to give me lessons in Chinese, and we began at once, even before we left Khotan.[187][188]..........

Thus the young Chinaman's proud dream of one day riding through the gates of Peking and beholding the palace (yamen) of his fabulously mighty emperor, as well as of perhaps securing, through my recommendation, a lucrative post, and finally, though by no means last in his estimation, of exchanging the Turki wife he had left behind in Khotan for a Chinese bride—this proud dream was pricked at the foot of Arka-tagh. Sadly and silently he stood alone in the desert, gazing after us, as we continued our way towards the far-distant goal of his youthful ambition.[189][190]

Uyghur prostitutes were encountered by Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim who wrote they were especially to be found in Khotan.[191][192][193] He commented on "venereal diseases".[194]

Different ethnic groups had different attitudes toward prostitution. George W. Hunter (missionary) noted that while Tungan Muslims (Chinese Muslims) would almost never prostitute their daughters, Turki Muslims (Uyghurs) would prostitute their daughters, which was why Turki prostitutes were common around the country.[195]

An anti-Russian uproar broke out when Russian customs officials, 3 Cossacks and a Russian courier invited local Turki Muslim (Uyghur) prostitutes to a party in January 1902 in Kashgar, this caused a massive brawl by the inflamed local Turki Muslim populace against the Russians on the pretense of protecting Muslim women because there was anti-Russian sentiment being built up, even though morality was not strict in Kashgar, the local Turki Muslims violently clashed with the Russians before they were dispersed, the Chinese sought to end to tensions to prevent the Russians from building up a pretext to invade.[196][197][198]

After the riot, the Russians sent troops to Sarikol in Tashkurghan and demanded that the Sarikol postal services be placed under Russian supervision, the locals of Sarikol believed that the Russians would seize the entire district from the Chinese and send more soldiers even after the Russians tried to negotiate with the Begs of Sarikol and sway them to their side, they failed since the Sarikoli officials and authorities demanded in a petition to the Amban of Yarkand that they be evacuated to Yarkand to avoid being harassed by the Russians and objected to the Russian presence in Sarikol, the Sarikolis did not believe the Russian claim that they would leave them alone and only involved themselves in the mail service.[199][200]

Le Coq reported that in his time sometimes Turkis distrusted Tungans (Hui Muslims) more than Han Chinese, so that a Tungan would never be given a Turki woman in marriage by her father, while a (Han) Chinese men could be given a Turki woman in marriage by her father.[201]

In Kashgar in 1933 the Chinese kept concubines and spouses who were Turkic women.[202]

Swedish Christian missionaries observed the oppressive conditions for Uyghur Muslim women in Xinjiang during their stay there. While Uyghur Muslim women were oppressed, by comparison Han Chinese women were free and few of them bothered to become maids unlike Uyghur Muslim women.[203] The lack of Han Chinese women led to Uyghur Muslim women marrying Han Chinese men. These women were hate by their families and people. The Uighur Muslims viewed single unmarried women as prostitutes and held them in extreme disregard.[204] Child marriages for girls was very common and the Uyghurs called girls "overripe" if they were not married by 15 or 16 years old. 4 wives were allowwd along with any amount of temporary marriages contracted by Mullahs to "pleasure wives" for a set time period.[205] Some had 60 and 35 wives. Divorces and marrying was rampant with marriages and divorces being conducted by Mullahs simultaneously and some men married hundreds and could divorce women for no reason. Wives were forced to stay in the house and had to be obedient to their husbands and were judged according to how much children they could bear. Unmarried Muslim Uyghur women married non-Muslims like Chinese, Hindus, Armenians, Jews, and Russians if they could not find a Muslim husband while they were calling to Allah to grant them marriage by the shrines of saints. Unmarried women were viewed as whores and many children were born with venereal diseases because of these.[206] The birth of a girl was seen as a terrible calamity by the local Uighur Muslims and boys were worth more to them. The constant stream of marriage and divorces led to children being mistreated by stepparents.[207] A Swedish missionary said "These girls were surely the first girls in Eastern Turkestan who had had a real youth before getting married. The Muslim woman has no youth. Directly from childhood’s carefree playing of games she enters life’s bitter everyday toil… She is but a child and a wife." The marriage of 9 year old Aisha to the Prophet Muhammad was cited by Uyghur Muslims to justify marrying girl children, whom they viewed as mere products. The Muslims also attacked the Swedish Christian mission and Hindus resident in the city.[208]

Lobbying by the Swedish Christian missionaries led to child marriage for under 15 year old girls to be banned by the Chinese Governor in Urumchi although the Uyghur Muslims ignored the law. Uyghur women converts to Christianity did not wear the veil and local Uyghur Muslim women were inspired by the Swedish missionary Christian women to be independent and pursue education instead of marriage, saying “Look at the Swedes, they remain single their whole lives if they want to.”, and one man was astonished that Jesus had a conversation with the Samaritan woman.[209]

Veiling

In the 1930s during the Kumul Rebellion the traveller Ahmad Kamal was asked by Turki (Uyghur) men if the veils donned by Turki women in Xinjiang were also worn by women in America (Amerikaluk).[210] The label of "whores" (Jilops) was used for Russian (Russ) and American (Amerikaluk) women by Turki men when what these women wore in public while bathing and the fact that no veil was worn by them was described by Ahmad Kamal to the Turki men.[211] Nomadic women did not wear the face veil and neither did peasant women. It was urban rich women who wore the face veil. Ahmad Kamal saw an unveiled peasant woman Jennett Han.[212] The face veil was only allowed to be taken off in the house and where just their husbands and fellow women could see them.[213] Veils were dropped by young women while the old "hags" were angry when boudoir in the gardens of Turki women were spied on by Ahmad Kamal and his companions.[214][215] Veils were worn by Turki women.[216]