Falaise Pocket

| Falaise Pocket | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Overlord, Battle of Normandy | |||||||

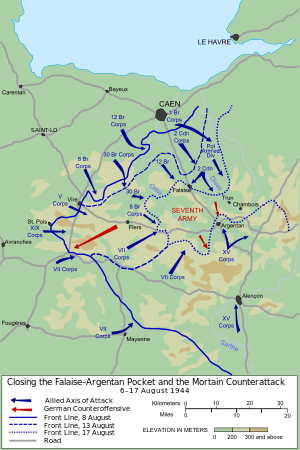

Map showing the course of the battle from 8–17 August 1944 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| Panzergruppe Eberbach | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| up to 17 divisions | 14–15 divisions | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

United States: Unknown United Kingdom: Unknown Free French: Unknown Canada: 5,679 casualties[nb 1] Poland: c. 5,150 casualties in total[3] of which 2,300 for the 1st. Armoured Division.[4] |

c. 60,000:

| ||||||

The Falaise Pocket or Battle of the Falaise Pocket (12 – 21 August 1944) was the decisive engagement of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. A pocket was formed around Falaise, Calvados, in which the German Army Group B, with the 7th Army and the Fifth Panzer Army (formerly Panzergruppe West) were encircled by the Western Allies. The battle is also referred to as the Battle of the Falaise Gap (after the corridor which the Germans sought to maintain to allow their escape), the Chambois Pocket, the Falaise-Chambois Pocket, the Argentan–Falaise Pocket or the Trun–Chambois Gap. The battle resulted in the destruction of most of Army Group B west of the Seine, which opened the way to Paris and the Franco-German border for the Allied armies on the Western Front.

Six weeks after D-Day, the Allied invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944, the German Army was in turmoil. While the Allied Army experienced great difficulty in breaking through the German lines (the city of Caen was supposed to have been captured on the first day of the invasion and was not taken until late in July) the German Army's defence of this area of Normandy was expending irreplaceable resources. The Allied air forces controlled the skies (up to 100 km behind enemy lines), bombing and strafing Axis troops, reinforcements, and necessary army supplies, such as fuel and ammunition.[5] On the Eastern Front, the Soviet Union's Operation Bagration and the Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive were in the midst of destroying the German Army Group Centre. In France, the German Army had used its available reserves (especially its armour reserves) to buttress the front lines around Caen, and there were few additional troops available to create successive lines of defence. To make matters worse, the 20 July plot—in which officers of the German Army, including some stationed in France, tried to assassinate Adolf Hitler and seize power—had failed, and in its aftermath there was very little trust between Hitler and his generals.

In order to break out of Normandy, the Allied armies developed a multi-stage operation. It started with a British and Canadian attack along the eastern battle line around Caen in Operation Goodwood on 18 July. The German Army responded by sending a large portion of its armoured reserves to defend. Then, on 25 July thousands of American bombers carpet bombed a 6,000-metre hole on the western end of the German lines around Saint-Lô in Operation Cobra, allowing the Americans to push forces through this gap in the German lines. After some initial resistance, the German forces were overwhelmed and the Americans broke through. On 1 August, Lieutenant General George S. Patton was named the commanding officer of the newly recommissioned US Third Army—which included large segments of the soldiers that had broken through the German lines—and with few German reserves behind the front line, the race was on. The Third Army quickly pushed south and then east, meeting very little German resistance. Concurrently, the British and Canadian troops pushed south (Operation Bluecoat) in an attempt to keep the German armour engaged. Under the weight of this British and Canadian attack, the Germans withdrew; the orderly withdrawal eventually collapsed due to lack of fuel.

Despite lacking the resources to defeat the US breakthrough and simultaneous British and Canadian offensives south of Caumont and Caen, Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, the commander of Army Group B, was not permitted by Hitler to withdraw but was ordered to conduct a counter-offensive at Mortain against the US breakthrough. Four depleted panzer divisions were not enough to defeat the First US Army. The disastrous Operation Lüttich drove the Germans deeper into the Allied envelopment.

On 8 August, the Allied ground forces commander, General Bernard Montgomery, ordered the Allied armies to converge on the Falaise–Chambois area to envelop Army Group B, with the First US Army forming the southern arm, the British the base, and the Canadians the northern arm of the encirclement. The Germans began to withdraw on 17 August, and on 19 August the Allies linked up in Chambois. Gaps were forced in the Allied lines by German counter-attacks, the biggest being a corridor forced past the 1st Polish Armoured Division on Hill 262, a commanding position at the mouth of the pocket. By the evening of 21 August, the pocket had been sealed, with c. 50,000 Germans trapped inside. Many Germans escaped, but losses in men and equipment were huge. A few days later, the Allied Liberation of Paris was completed, and on 30 August the remnants of Army Group B retreated across the Seine, which ended Operation Overlord.

Background

Operation Overlord

Early Allied objectives in the wake of the D-Day invasion of German-occupied France included the deep water port of Cherbourg and the area surrounding the town of Caen.[6] Allied attacks to expand the bridgehead had rapidly defeated the initial German attempts to destroy the invasion force, but bad weather in the English Channel delayed the Allied build-up of supplies and reinforcements, while enabling the Germans to move troops and supplies with less interference from the Allied air forces.[7][8] Cherbourg was not captured by the VII US Corps until 27 June, and the German defence of Caen lasted until 20 July, when the southern districts were taken by the British and Canadians in Operation Goodwood and Operation Atlantic.[9][10]

General Bernard Montgomery, the Allied ground forces commander, had planned a strategy of attracting German forces to the east end of the bridgehead against the British and Canadians, while the US First Army advanced down the west side of the Cotentin Peninsula to Avranches.[11] On 25 July the US First Army commander, Lieutenant-General Omar Bradley, began Operation Cobra.[12] The US First Army broke through the German defences near Saint-Lô and by the end of the third day had advanced 15 mi (24 km) south of its start line at several points.[13][14] Avranches was captured on 30 July and within 24 hours the US VIII Corps of the US Third Army crossed the bridge at Pontaubault into Brittany and continued south and west through open country, almost without opposition.[15][16][17]

Operation Lüttich

The US advance was swift and by 8 August, Le Mans, the former headquarters of the German 7th Army, had been captured.[18] After Operation Cobra, Operation Bluecoat and Operation Spring, the German army in Normandy was so reduced that "only a few SS fanatics still entertained hopes of avoiding defeat".[19] On the Eastern Front, Operation Bagration had begun against Army Group Centre which left no possibility of reinforcement of the Western Front.[19] Adolf Hitler sent a directive to Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, the replacement commander of Army Group B after the sacking of Gerd von Rundstedt, ordering "an immediate counter-attack between Mortain and Avranches" to "annihilate" the enemy and make contact with the west coast of the Cotentin peninsula.[20][21]

Eight of the nine Panzer divisions in Normandy were to be used in the attack, but only four could be made ready in time.[22] The German commanders protested that their forces were incapable of an offensive, but the warnings were ignored and Operation Lüttich commenced on 7 August around Mortain.[21][23] The first attacks were made by the 2nd Panzer Division, SS Division Leibstandarte and the SS Division Das Reich, but they had only 75 Panzer IVs, 70 Panthers and 32 self-propelled guns.[24] The Allies were forewarned by Ultra signals intercepts, and although the offensive continued until 13 August, the threat of Operation Lüttich had been ended within 24 hours.[25][26][27] Operation Lüttich had led to the most powerful remaining German units being defeated at the west side of the Cotentin Peninsula by the US First Army, and the Normandy front on the verge of collapse.[28][29] Bradley said

This is an opportunity that comes to a commander not more than once in a century. We're about to destroy an entire hostile army and go all the way from here to the German border.[29]

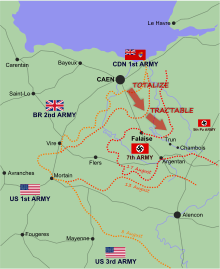

Operation Totalize

The First Canadian Army was ordered to capture high ground north of Falaise to trap Army Group B.[30] The Canadians planned Operation Totalize, with attacks by strategic bombers and a novel night attack using Kangaroo armoured personnel carriers.[31][32] Operation Totalize began on the night of 7/8 August; the leading infantry rode on the Kangaroos, guided by electronic aids and illuminants, against the 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend, which held a 14 km (8.7 mi) front, supported by the 101st SS Heavy Panzer Battalion and remnants of the 89th Infantry Division.[31][33] Verrières Ridge and Cintheaux were captured on 9 August, but the speed of the advance was slowed by German resistance and some poor Canadian unit leadership, which led to many casualties in the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and 1st Polish Armoured Division.[34][35][36] By 10 August, Anglo-Canadian forces had reached Hill 195, north of Falaise.[36] The following day, Canadian commander Guy Simonds relieved the armoured divisions with infantry divisions, ending the offensive.[37]

Prelude

Allied plan

Still expecting Kluge to withdraw his forces from the tightening Allied noose, Montgomery had for some time been planning a "long envelopment", by which the British and Canadians would pivot left from Falaise toward the River Seine while the US Third Army blocked the escape route between the Seine and the Loire, trapping all surviving German forces in western France.[38][nb 2] In a telephone conversation on 8 August, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, recommended an American proposal for a shorter envelopment at Argentan. Montgomery and Patton had misgivings; if the Allies did not take Argentan, Alençon and Falaise quickly, many Germans might escape. Believing he could always fall back on the original plan if necessary, Montgomery accepted the wishes of Bradley as the man on the spot, and the proposal was adopted.[38]

Battle

Operation Tractable

The Third Army advance from the south made good progress on 12 August; Alençon was captured and Kluge was forced to commit troops he had been gathering for a counter-attack. The next day, the US 5th Armored Division of the US XV Corps advanced 35 mi (56 km) and reached positions overlooking Argentan.[40] On 13 August, Bradley over-ruled orders by Patton for a further push northwards towards Falaise by the 5th Armored Division.[40] Bradley instead ordered the XV Corps to "concentrate for operations in another direction".[41] The US troops near Argentan were ordered to withdraw, which ended the pincer movement by the XV Corps.[42] Patton objected but complied, which left an exit for the German forces in the Falaise Pocket.[42][nb 3]

With the Americans on the southern flank halted and then engaged with Panzer Group Eberbach, and with the British pressing in from the north-west, the First Canadian Army, which included the Polish 1st Armoured Division, was ordered to close the trap.[44] After a limited attack by the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division down the Laize valley on 12–13 August, most of the time since Totalize had been spent preparing for Operation Tractable, a set-piece attack on Falaise.[35] The operation commenced on 14 August at 11:42, covered by an artillery smokescreen that mimicked the night attack of Operation Totalize.[35][45] The 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the 1st Polish Armoured Division crossed the Laison, but delays at the River Dives gave time for the Tiger tanks of the schwere SS-Panzer Abteilung 102 to counter-attack.[45]

Navigating through the smoke slowed progress, and the mistaken use by the First Canadian Army of yellow smoke to identify their positions—the same colour strategic bombers used to mark targets—led to some bombing of the Canadians and slower progress than planned.[46][47] On 15 August, the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions and the 2nd Canadian (Armoured) Brigade continued the offensive, but progress remained slow.[47][48] The 4th Armoured Division captured Soulangy against determined German resistance and several German counter-attacks, which prevented a breakthrough to Trun.[49] The next day, the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division entered Falaise against minor opposition from Waffen SS units and scattered pockets of German infantry, and by 17 August had secured the town.[50]

At midday on 16 August, Kluge had refused an order from Hitler for another counter-attack, and in the afternoon Hitler agreed to a withdrawal but became suspicious that Kluge intended to surrender to the Allies.[47][51] Late on 17 August, Hitler sacked Kluge and recalled him to Germany; Kluge then either killed himself or was executed by SS-officer Jürgen Stroop for his involvement in the 20 July plot.[52][53] Kluge was succeeded by Field Marshal Walter Model, whose first act was to order the immediate retreat of the 7th Army and Fifth Panzer Army, while the II SS Panzer Corps—with the remnants of four Panzer divisions—held the north face of the escape route against the British and Canadians, and the XLVII Panzer Corps—with what was left of two Panzer divisions—held the southern face against the Third US Army.[52]

Encirclement

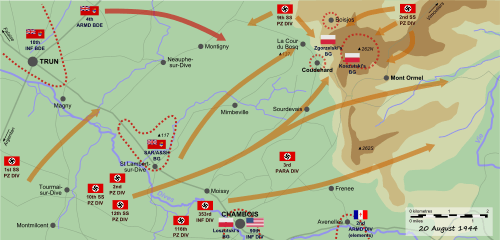

By 17 August the encirclement was incomplete.[52] The 1st Polish Armoured Division, part of the First Canadian Army, was divided into three battlegroups and ordered to make a wide sweep to the south-east to meet American troops at Chambois.[52] Trun fell to the 4th Canadian Armoured Division on 18 August.[54] Having captured Champeaux on 19 August, the Polish battlegroups converged on Chambois, and with reinforcements from the 4th Canadian Armoured Division, the Poles secured the town and linked up with the US 90th and French 2nd Armoured divisions by evening.[55][56][57] The Allies were not yet astride the 7th Army escape route in any great strength, and their positions were attacked by German troops inside the pocket.[57] An armoured column of the 2nd Panzer Division broke through the Canadians in St. Lambert, took half the village and kept a road open for six hours until nightfall.[55] Many Germans escaped, and small parties made their way through to the Dives during the night.[58]

Having taken Chambois, two of the Polish battlegroups drove north-east and established themselves on part of Hill 262 (Mont Ormel ridge), spending the night of 19 August digging in.[59] The following morning, Model ordered elements of the 2nd SS Panzer Division and 9th SS Panzer Division to attack from outside the pocket towards the Polish positions.[60] Around midday, several units of the 10th SS Panzer Division, 12th SS Panzer Division and 116th Panzer Division managed to break through the Polish lines and open a corridor, while the 9th SS Panzer Division prevented the Canadians from intervening.[61] By mid-afternoon, about 10,000 German troops had passed out of the pocket.[62]

The Poles held on to Hill 262 (The Mace), and were able from their vantage point to direct artillery fire on to the retreating Germans.[63] Paul Hausser, the 7th Army commander, ordered that the Polish positions be "eliminated".[62] The remnants of the 352nd Infantry Division and several battle groups from the 2nd SS Panzer Division inflicted many casualties on the 8th and 9th battalions of the Polish Division, but the assault was eventually repulsed at the cost of nearly all of their ammunition, and the Poles watched as the remnants of the XLVII Panzer Corps escaped. During the night there was sporadic fighting, and the Poles called for frequent artillery bombardments to disrupt the German retreat from the sector.[63]

German attacks resumed the next morning, but the Poles retained their foothold on the ridge. At about 11:00, a final attempt on the positions of the 9th Battalion was launched by nearby SS troops, which was defeated at close quarters.[64] Soon after midday, the Canadian Grenadier Guards reached Mont Ormel, and by late afternoon the remainder of the 2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions had begun their retreat to the Seine.[49][65] For the Falaise pocket operation, the 1st Polish Armoured Division listed 1,441 casualties including 466 killed,[66] while Polish casualties at Mont Ormel were 351 killed and wounded, with eleven tanks lost.[64] German losses in their assaults on the ridge were c. 500 dead and 1,000 men taken prisoner, most from the 12th SS-Panzer Division. Scores of Tiger, Panther and Panzer IV tanks were destroyed, along with many artillery pieces.[64]

By the evening of 21 August, tanks of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division had linked with Polish forces at Coudehard, and the 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry divisions had secured St. Lambert and the northern passage to Chambois; the Falaise pocket had been sealed.[67] Approximately 20–50,000 German troops, minus heavy equipment, escaped through the gap and were reorganized and rearmed, in time to slow the Allied advance into the Netherlands and Germany.[42]

Aftermath

Analysis

The Battle of the Falaise Pocket ended the Battle of Normandy with a decisive German defeat.[1] Hitler's involvement had been damaging from the first, with his insistence on hopelessly unrealistic counter-offensives, micro-management of generals, and refusal to countenance withdrawal when his armies were threatened with annihilation.[68] More than forty German divisions were destroyed during the Battle of Normandy. No exact figures are available, but historians estimate that the battle cost the German forces c. 450,000 men, of whom 240,000 were killed or wounded.[68] The Allies had achieved victory at a cost of 209,672 casualties among the ground forces, including 36,976 killed and 19,221 missing.[67] The Allied air forces lost 16,714 airmen killed or missing in connection with Operation Overlord.[69] The final battle of Operation Overlord, the Liberation of Paris, followed on 25 August, and Overlord ended by 30 August, with the retreat of the last German unit across the Seine.[70]

The area in which the pocket had formed was full of the remains of battle.[71] Villages had been destroyed, and derelict equipment made some roads impassable. Corpses of soldiers and civilians littered the area, along with thousands of dead cattle and horses.[72] In the hot August weather, maggots crawled over the bodies, and swarms of flies descended on the area.[72][73] Pilots reported being able to smell the stench of the battlefield hundreds of feet above it.[72] General Eisenhower recorded that:

The battlefield at Falaise was unquestionably one of the greatest "killing fields" of any of the war areas. Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap I was conducted through it on foot, to encounter scenes that could be described only by Dante. It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.[74]

— Dwight Eisenhower

Fear of infection from the rancid conditions led the Allies to declare the area an "unhealthy zone".[75] Clearing the area was a low priority though, and went on until well into November. Many swollen bodies had to be shot to expunge gasses within them before they could be burnt, and bulldozers were used to clear the area of dead animals.[72][73]

Disappointed that a significant portion of the 7th Army had escaped from the pocket, many Allied commanders, particularly among the Americans, were critical of what they perceived as Montgomery's lack of urgency in closing the pocket.[76] Writing shortly after the war, Ralph Ingersoll—a prominent peacetime journalist, who had served as a planner on Eisenhower's staff—expressed the prevailing American view at the time:

The international army boundary arbitrarily divided the British and American battlefields just beyond Argentan, on the Falaise side of it. Patton's troops, who thought they had the mission of closing the gap, took Argentan in their stride and crossed the international boundary without stopping. Montgomery, who was still nominally in charge of all ground forces, now chose to exercise his authority and ordered Patton back to his side of the international boundary line. For ten days, however, the beaten but still coherently organized German Army retreated through the Falaise gap.[77]

— Ralph Ingersoll

Some historians have thought that the gap could have been closed earlier; Wilmot wrote that despite having British divisions in reserve, Montgomery did not reinforce Guy Simonds and that the Canadian drive on Trun and Chambois was not "vigorous and venturesome" as the situation demanded.[76] The British author and historian Max Hastings wrote that Montgomery, having witnessed what he called a poor Canadian performance during Totalize, should have brought up veteran British divisions to take the lead.[38] D'Este and Blumenson wrote that Montgomery and Harry Crerar might have done more to impart momentum to the British and Canadians. Patton's post-battle claim that the Americans could have prevented the German escape, had Bradley not ordered him to stop at Argentan, was "absurd over-simplification".[78]

Wilmot wrote that "contrary to contemporary reports, the Americans did not capture Argentan until 20 August, the day after the link up at Chambois".[79] The American unit that closed the gap between Argentan and Chambois, the 90th Division, was according to Hastings one of the least effective of any Allied army in Normandy. He speculated that the real reason Bradley halted Patton was not fear of accidental clashes with the British, but knowledge that, with powerful German formations still operational, the Americans lacked the means to defend an early blocking position and would have suffered an "embarrassing and gratuitous setback" at the hands of the retreating Fallschirmjäger and the 2nd and 12th SS-Panzer divisions.[78] Bradley wrote after the war that:

Although Patton might have spun a line across the narrow neck, I doubted his ability to hold it. Nineteen German divisions were now stampeding to escape the trap. Meanwhile, with four divisions George was already blocking three principal escape routes through Alencon, Sees and Argentan. Had he stretched that line to include Falaise, he would have extended his roadblock a distance of 40 miles (64 km). The enemy could not only have broken through, but he might have trampled Patton's position in the onrush. I much preferred a solid shoulder at Argentan to the possibility of a broken neck at Falaise.[80]

— Omar Bradley

Casualties

By 22 August, all German forces west of the Allied lines were dead or in captivity.[81] Historians differ in their estimates of German losses in the pocket. The majority state that from 80,000–100,000 troops were caught in the encirclement, of whom 10,000–15,000 were killed, 40,000–50,000 were taken prisoner, and 20,000–50,000 escaped. Shulman, Wilmot and Ellis estimated that the remnants of 14–15 divisions were in the pocket. D'Este gave 80,000 troops trapped, of whom 10,000 were killed, 50,000 captured and 20,000 escaped.[82] Shulman gives c. 80,000 trapped, 10–15,000 killed and 45,000 captured.[83] Wilmot recorded 100,000 trapped, 10,000 killed and 50,000 captured.[84] Williams wrote that c. 100,000 German troops escaped.[1] Tamelander estimated that 50,000 German troops were caught, of whom 10,000 were killed and 40,000 taken prisoner, while perhaps another 50,000 escaped.[85] In the northern sector, German losses included 344 tanks, self-propelled guns and other light armoured vehicles, as well as 2,447 soft-skinned vehicles and 252 guns abandoned or destroyed.[67][86] In the fighting around Hill 262, German losses totalled 2,000 men killed, 5,000 taken prisoner and 55 tanks, 44 guns and 152 other armoured vehicles destroyed.[87] The 12th SS-Panzer Division had lost 94 percent of its armour, nearly all of its artillery and 70 percent of its vehicles. With close to 20,000 men and 150 tanks before the Normandy campaign, after Falaise it was reduced to 300 men and 10 tanks.[65] Although elements of several German formations had managed to escape to the east, even these had left behind most of their equipment.[88] After the battle, Allied investigators estimated that the Germans lost around 500 tanks and assault guns in the pocket, and that little of the extricated equipment survived the retreat across the Seine.[76]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ From 8 until 21 August: 1,479 killed or died of wounds, 4,023 wounded or injured, and 177 captured.[2]

- ↑ Divisions around the Falaise Pocket on 16 August 1944: First Canadian Army, 1st Polish Armoured Division, 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, 4th Canadian Armoured Division; Second British Army: 3rd Infantry Division, 11th Armoured Division, 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, 53rd (Welsh) Infantry Division, 59th (Staffordshire) Infantry Division; First United States Army: US 1st Infantry Division, US 3rd Armored Division, US 9th Infantry Division, US 28th Infantry Division, US 30th Infantry Division; Third United States Army: French 2nd Armoured Division, 90th Infantry Division.[39]

- ↑ Bradley later received much blame for "failing" to exploit the opportunity to envelop Army Group B.[40] General Hans Speidel, Chief of Staff of Army Group B, wrote that they would have been eliminated, if the 5th Armored Division had continued its advance to Falaise, although D'Este wrote that the order came from Montgomery.[42][43]

Citations

- 1 2 3 Williams, p. 204

- ↑ Stacey, p. 271

- ↑ "World War II: Closing the Falaise Pocket". History Net. Retrieved 12 August 2017.

- ↑ "The Canadians in the Falaise Pocket". Info-Poland. Archived from the original on 2 July 2010.

- ↑ Liddell-Hart, pp. 476–478

- ↑ Van der Vat, p. 110

- ↑ Williams, p. 114

- ↑ Griess, pp. 308–310

- ↑ Hastings, p. 165

- ↑ Trew, p. 48

- ↑ Hart, p. 38.

- ↑ Wilmot, pp. 390–392

- ↑ Hastings, p. 257.

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 393.

- ↑ Williams, p. 185

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 394

- ↑ Hastings, p. 280

- ↑ Williams, p. 194

- 1 2 Hastings, p. 277

- ↑ D'Este, p. 414

- 1 2 Williams, p. 196

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 401

- ↑ Hastings, p. 283

- ↑ Hastings, p. 285

- ↑ Messenger, pp. 213–217

- ↑ Bennett 1979, pp. 112–119

- ↑ Hastings, p. 286

- ↑ Hastings, p. 335

- 1 2 Williams, p. 197

- ↑ D'Este, p. 404

- 1 2 Hastings, p. 296

- ↑ Zuehlke, p. 168

- ↑ Williams, p. 198

- ↑ Hastings, p. 299

- 1 2 3 Hastings, p. 301

- 1 2 Bercuson, p. 230

- ↑ Hastings, p. 300

- 1 2 3 Hastings, p. 353.

- ↑ Copp (2003), p. 234.

- 1 2 3 Wilmot, p. 417

- ↑ Essame, p. 168

- 1 2 3 4 Essame, p. 182

- ↑ D'Este, p. 441

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 419

- 1 2 Bercuson, p. 231

- ↑ Hastings, p. 354

- 1 2 3 Hastings, p. 302

- ↑ Van Der Vat, p. 169

- 1 2 Bercuson, p. 232

- ↑ Copp (2006), p. 104

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 420

- 1 2 3 4 Hastings, p. 303

- ↑ Moczarski, 1981, pp. 226–234

- ↑ Zuehlke, p. 169

- 1 2 Wilmot, p. 422

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 192

- 1 2 Hastings, p. 304

- ↑ Wilmot, p.423

- ↑ D'Este, p. 456

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 195

- ↑ Jarymowycz, p. 196

- 1 2 Van Der Vat, p. 168

- 1 2 D'Este, p. 458

- 1 2 3 McGilvray, p. 54

- 1 2 Bercuson, p. 233

- ↑ Copp (2003), p. 249

- 1 2 3 Hastings, p. 313

- 1 2 Williams, p. 205

- ↑ Tamelander, Zetterling, p. 341.

- ↑ Hastings, p. 319

- ↑ Hastings, p. 311

- 1 2 3 4 Lucas & Barker, p. 158

- 1 2 Hastings, p. 312

- ↑ Eisenhower 1948, p. 279

- ↑ Lucas & Barker, p. 159

- 1 2 3 Wilmot, p. 424

- ↑ Ingersoll 1946, pp. 190–91

- 1 2 Hastings, p. 369

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 425

- ↑ Bradley, p. 377

- ↑ Hastings, p. 306

- ↑ D'Este, pp. 430–431

- ↑ Shulman, pp. 180, 184

- ↑ Wilmot, pp. 422, 424

- ↑ Tamelander, Zetterling, p. 342

- ↑ Reynolds, p. 88

- ↑ McGilvray, p. 55

- ↑ Hastings, p. 314

References

- Bennett, R. (1979). Ultra in the West: The Normandy Campaign of 1944–1945. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-139330-2.

- Bercuson, D. (2004) [1996]. Maple Leaf Against the Axis. Markham, Ontario: Red Deer Press. ISBN 0-88995-305-8.

- Bradley, Omar (1999) [1951]. A Soldier's Story. Modern Library. New York: Holt. ISBN 978-037-575421-0.

- Copp, T. (2006). Cinderella Army: The Canadians in Northwest Europe, 1944–1945. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-3925-1.

- ——— (2007) [2003]. Fields of Fire: The Canadians in Normandy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-3780-0.

- D'Este, Carlo (2004) [1983]. Decision in Normandy: The Real Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-141-01761-9.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1948). Crusade in Europe. New York: Doubleday.

- Ellis, Major L.F.; Allen, Captain G.R.G., R.N.; Warhurst, Lieutenant-Colonel A.E. & Robb, Air Chief-Marshal Sir James (2004) [1962]. Butler, J.R.M., ed. Victory in the West: The Battle of Normandy. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military. I (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 1-84574-058-0.

- Essame, H. (1988) [1973]. Patton: as Military Commander. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-585-10019-7.

- Griess, T. (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean. United States Military Academy West Point, New York: Square One. ISBN 0-7570-0160-2.

- Hart, S.A. (2007) [2000]. Colossal Cracks: Montgomery's 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944–45. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-3383-1.

- Hastings, M. (2006) [1985]. Overlord: D-Day and the Battle for Normandy (reprint ed.). New York: Vintage Books USA. ISBN 0-307-27571-X.

- Ingersoll, Ralph (1946). Top Secret. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Jarymowycz, R. (2001). Tank Tactics: from Normandy to Lorraine. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-950-0.

- Liddell Hart, B.H. (1953). The Rommel Papers (15 ed.). New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Lucas, James; Barker, James (1978). The Killing Ground, The Battle of the Falaise Gap, August 1944. London: B T Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-0433-7.

- McGilvray, Evan (2004). The Black Devils' March – A Doomed Odyssey – The 1st Polish Armoured Division 1939–45. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-874622-42-0.

- Messenger, Charles (1999). The Illustrated Book of World War II. San Diego, California: Thunder Bay. ISBN 1-57145-217-6.

- Moczarski, K.; Fitzpatrick, Mariana; Stroop, Jürgen (1981). Conversations with an Executioner. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-171918-1.

- Reynolds, Michael (2002). Sons of the Reich: The History of II SS Panzer Corps in Normandy, Arnhem, the Ardennes and on the Eastern Front. Philadelphia: Casemate. ISBN 0-9711709-3-2.

- Shulman, M. (2007) [1947]. Defeat in the West. Whitefish, MN: Kessinger. ISBN 0-548-43948-6.

- Stacey, Colonel C. P.; Bond, Major C.C.J. (1960). "The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945" (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery, Ottawa. OCLC 606015967. Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- Tamelander, Michael; Zetterling, Niklas (2003) [1995]. Avgörandes ögonblick: Invasionen i Normandie 1944 [The moment of decision: The invasion of Normandy 1944] (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedts förlag. ISBN 91-1-301204-5.

- Trew, Simon; Badsey, Stephen (2004). Battle for Caen. Battle Zone Normandy. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 0-7509-3010-1.

- van der Vat, Dan (2003). D-Day; The Greatest Invasion, A People's History. Aurora, Illinois: Madison Press. ISBN 1-55192-586-9.

- Williams, A. (2004). D-Day to Berlin. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-83397-1.

- Wilmot, Chester; McDevitt, C.D. (1997) [1952]. The Struggle for Europe. Ware: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

- Zuehlke, Mark (2001). The Canadian Military Atlas: Canada's Battlefields from the French and Indian Wars to Kosovo. North York, Ontario: Stoddart. ISBN 0-7737-3289-6.

Further reading

- Keegan, J. (2006). Atlas of World War II. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-089077-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Falaise Pocket. |

- British Broadcasting Corporation. "Account of the Polish battle on hill 262".

- "canadiansoldiers.com: Falaise".

- "Canada at War: Canadians in the Falaise Gap".

- "Canada at War: The Battle of Hill 195".

- "Canada at War: The Battle at St. Lambert-Sur-dives".

- Richard, Duda; Steven, Duda. "Captain Kazimierz DUDA - 1st Polish Armoured Division".

- Wiacek, Jacques. "Closing of the Falaise Pocket". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- "Film footage of the battle".

- "Chapter 4. Polish military operations in West-Europe since 1944". Polish forces in the West. Retrieved 10 January 2016.