Yarn

Yarn is a long continuous length of interlocked fibres, suitable for use in the production of textiles, sewing, crocheting, knitting, weaving, embroidery, or ropemaking.[1] Thread is a type of yarn intended for sewing by hand or machine. Modern manufactured sewing threads may be finished with wax or other lubricants to withstand the stresses involved in sewing.[2] Embroidery threads are yarns specifically designed for needlework.

Etymology

The word yarn comes from Middle English, from the Old English gearn, akin to Old High German's garn yarn, Greek's chordē string, and Sanskrit's hira band.[1] And in India in Hindi they said Dhaga.

Materials

Yarn can be made from a number of natural or synthetic fibers. Many types of yarn are made differently though. There are two main types of yarn: spun and filament.

Fibers

The most common plant fiber is cotton, which is typically[3] spun into fine yarn for mechanical weaving or knitting into cloth.

Cotton and polyester are the most commonly spun fibers in the world. Cotton is grown throughout the world. After harvesting it is ginned and prepared for yarn spinning. Polyester is extruded from polymers derived from natural gas and oil. Synthetic fibers are generally extruded in continuous strands of gel-state materials. These strands are drawn (stretched), annealed (hardened), and cured to obtain properties desirable for later processing.

Synthetic fibers come in three basic forms: staple, tow, and filament. Staple is cut fibers, generally sold in lengths up to 120mm. Tow is a continuous "rope" of fibers consisting of many filaments loosely joined side-to-side. Filament is a continuous strand consisting of anything from 1 filament to many. Synthetic fiber is most often measured in a weight per linear measurement basis, along with cut length. Denier and Dtex are the most common weight to length measures. Cut-length only applies to staple fiber.

Filament extrusion is sometimes referred to as "spinning" but most people equate spinning with spun yarn production.

The most commonly spun animal fiber is wool harvested from sheep. For hand knitting and hobby knitting, thick, wool and acrylic yarns are frequently used.

Other animal fibers used include alpaca, angora, mohair, llama, cashmere, and silk. More rarely, yarn may be spun from camel, yak, possum, musk ox, cat, dog, wolf, rabbit, or buffalo hair, and even turkey or ostrich feathers. Natural fibers such as these have the advantage of being slightly elastic and very breathable, while trapping a great deal of air, making for a fairly warm fabric.

Other natural fibers that can be used for yarn include linen[4] and cotton.[5] These tend to be much less elastic, and retain less warmth than the animal-hair yarns, though they can be stronger in some cases. The finished product will also look rather different from the woollen yarns. Other plant fibers which can be spun include bamboo, hemp, corn, nettle, and soy fiber.

Comparison of material properties

In general, natural fibers tend to require more careful handling than synthetics because they can shrink, felt, stain, shed, fade, stretch, wrinkle, or be eaten by moths more readily, unless special treatments such as mercerization or superwashing are performed to strengthen, fix color, or otherwise enhance the fiber's own properties.

Protein yarns (i.e., hair, silk, feathers) may also be irritating to some people, causing contact dermatitis, hives, wheezing, or other reactions. Plant fibers tend to be better tolerated by people with sensitivities to the protein yarns, and allergists may suggest using them or synthetics instead to prevent symptoms. Some people find that they can tolerate organically grown and processed versions of protein fibers, possibly because organic processing standards preclude the use of chemicals that may irritate the skin.

When natural hair-type fibers are burned, they tend to singe and have a smell of burnt hair; this is because many, as human hair, are protein-derived. Cotton and viscose (rayon) yarns burn as a wick. Synthetic yarns generally tend to melt though some synthetics are inherently flame-retardant. Noting how an unidentified fiber strand burns and smells can assist in determining if it is natural or synthetic, and what the fiber content is.

Both synthetic and natural yarns can pill. Pilling is a function of fiber content, spinning method, twist, contiguous staple length, and fabric construction. Single ply yarns or using fibers like merino wool are known to pill more due to the fact that in the former, the single ply is not tight enough to securely retain all the fibers under abrasion, and the merino wool's short staple length allows the ends of the fibers to pop out of the twist more easily.

Yarns combining synthetic and natural fibers inherit the properties of each parent, according to the proportional composition. Synthetics are added to lower cost, increase durability, add unusual color or visual effects, provide machine washability and stain resistance, reduce heat retention or lighten garment weight.

Structure

Spun yarn is made by twisting staple fibres together to make a cohesive thread, or "single."[6] Twisting fibres into yarn in the process called spinning can be dated back to the Upper Paleolithic,[7] and yarn spinning was one of the very first processes to be industrialized. Spun yarns may contain a single type of fibre, or be a blend of various types. Combining synthetic fibres (which can have high strength, lustre, and fire retardant qualities) with natural fibres (which have good water absorbency and skin comforting qualities) is very common. The most widely used blends are cotton-polyester and wool-acrylic fibre blends. Blends of different natural fibres are common too, especially with more expensive fibres such as alpaca, angora and cashmere.

Yarn is selected for different textiles based on the characteristics of the yarn fibres, such as warmth (wool), light weight (cotton or rayon), durability (nylon is added to sock yarn, for example), or softness (cashmere, alpaca).

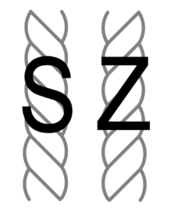

Yarn is composed of twisted strands of fiber, which are known as plies when grouped together.[8] These strands of yarn are twisted together (plied) in the opposite direction to make a thicker yarn. Depending on the direction of this final twist, the yarn will have either s‑twist (the threads appear to go "up" to the left) or z‑twist (to the right). For a single ply yarn, the direction of the final twist is the same as its original twist. The twist direction of yarn can affect the final properties of the fabric, and combined use of the two twist directions can nullify skewing in knitted fabric.[9]

The mechanical integrity of yarn is derived from frictional contacts between its composing fibers. The science behind this was first studied by Galileo.[10]

Filament yarn consists of filament fibres (very long continuous fibres) either twisted together or only grouped together. Thicker monofilaments are typically used for industrial purposes rather than fabric production or decoration. Silk is a natural filament, and synthetic filament yarns are used to produce silk-like effects.

Texturized yarns are made by a process of air texturizing filament yarns (sometimes referred to as taslanizing), which combines multiple filament yarns into a yarn with some of the characteristics of spun yarns. Slub Effect means a yarn with thick and thin sections alternating regularly or irregularly.It was invented by Mr. Rizwanul Karim from Bangladesh.

Colour

Yarn may be used undyed, or may be coloured with natural or artificial dyes. Most yarns have a single uniform hue, but there is also a wide selection of variegated yarns:

- Heathered or tweed: yarn with flecks of different coloured fibre

- Ombre: variegated yarn with light and dark shades of a single hue

- Multicolored: variegated yarn with two or more distinct hues (a "parrot colourway" might have green, yellow and red)

- Self-striping: yarn dyed with lengths of colour that will automatically create stripes in a knitted or crocheted object

- Marled: yarn made from strands of different-coloured yarn twisted together, sometimes in closely related hues

Yarn quantities for handcrafts are usually measured and sold by weight in ounces or grams. Common sizes include 25 g, 50 g, and 100 g skeins. Some companies also primarily measure in ounces with common sizes being three-ounce, four-ounce, six-ounce, and eight-ounce skeins. Textile measurements are taken at a standard temperature and humidity, because fibers can absorb moisture from the air. The actual length of the yarn contained in a ball or skein can vary due to the inherent heaviness of the fibre and the thickness of the strand; for instance, a 50 g skein of lace weight mohair may contain several hundred metres, while a 50 g skein of bulky wool may contain only 60 metres.

There are several thicknesses of craft yarn, also referred to as weight. This is not to be confused with the measurement and/or weight listed above. The Craft Yarn Council of America is making an effort to promote a standardized industry system for measuring this, numbering the weights from 1 (finest) to 6 (heaviest).[11] Some of the names for the various weights of yarn from finest to thickest are called lace, fingering, sport, double-knit (or DK), worsted, aran (or heavy worsted), bulky, and super-bulky. This naming convention is more descriptive than precise; fibre artists disagree about where on the continuum each lies, and the precise relationships between the sizes.

Another measurement of yarn weight, often used by weavers, is wraps per inch (WPI). The yarn is wrapped snugly around a ruler and the number of wraps that fit in an inch are counted.

Labels on yarn for handicrafts often include information on gauge, known in the UK as tension, which is a measurement of how many stitches and rows are produced per inch or per cm on a specified size of knitting needle or crochet hook. The proposed standardization uses a four-by-four inch/ten-by-ten cm knitted or crocheted square, with the resultant number of stitches across and rows high made by the suggested tools on the label to determine the gauge.

In Europe, textile engineers often use the unit tex, which is the weight in grams of a kilometre of yarn, or decitex, which is a finer measurement corresponding to the weight in grams of 10 km of yarn. Many other units have been used over time by different industries.

Fabric under digital USB microscope

Below are the images taken by a digital USB microscope. These show how the yarn looks in different kinds of clothes when magnified.

Woolen Shawl

Woolen Shawl.jpg) Woolen shawl under microscope

Woolen shawl under microscope Cloth Pencil Box

Cloth Pencil Box.jpg) Cloth Pencil Box under microscope

Cloth Pencil Box under microscope Jeans

Jeans.jpg) Jeans under microscope

Jeans under microscope Sweatshirt

Sweatshirt.jpg) Sweatshirt under microscope

Sweatshirt under microscope

See also

Notes

- 1 2 "Yarn". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2012-05-07. Retrieved 2012-05-25.

- ↑ Kadolph, Sara J., ed.: Textiles, 10th edition, Pearson/Prentice-Hall, 2007, ISBN 0-13-118769-4, p. 203

- ↑ "How yarn is made". Advameg. Archived from the original on 2007-06-16. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

- ↑ Johnson, Ingrid; Cohen, Allen C.; Sarkar, Ajoy K. (2015-09-24). J.J. Pizzuto's Fabric Science: Studio Access Card. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781628926583. Archived from the original on 2018-02-11.

- ↑ Juracek, Judy A. (2000). Soft Surfaces: Visual Research for Artists, Architects, and Designers. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393730333. Archived from the original on 2018-02-11.

- ↑ Kadolph, Textiles, p. 197

- ↑ Barber, Elizabeth Wayland, Women's Work:The First 20,000 Years, W. W. Norton, 1994, p. 44

- ↑ Doran, David; Cather, Bob (2013-07-24). Construction Materials Reference Book. Routledge. ISBN 9781135139216. Archived from the original on 2018-02-11.

- ↑ "How to Ply Yarn the Simple Way with this Expert Guide | Interweave". Interweave. 2016-11-18. Archived from the original on 2016-12-14. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ↑ Warren, Patrick B.; et al. (13 April 2018). "Why Clothes Don't Fall Apart: Tension Transmission in Staple Yarns". Physical Review Letters. 120. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.120.158001. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ↑ "Standards and Guidelines for Crochet and Knitting - Welcome to the Craft Yarn Council". www.yarnstandards.com. Archived from the original on 2007-04-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yarn. |