Singer Corporation

| |

| Founded | 1851 as I. M. Singer Company, New York, New York, United States |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | La Vergne, Tennessee, United States |

| Parent |

SVP Worldwide International Semi Tech Microsystems 1989-2000 |

| Website | singer.com |

Singer Corporation is an American manufacturer of sewing machines, first established as I. M. Singer & Co. in 1851 by Isaac Merritt Singer with New York lawyer Edward Clark. Best known for its sewing machines, it was renamed Singer Manufacturing Company in 1865, then The Singer Company in 1963. It is based in La Vergne, Tennessee, near Nashville. Its first large factory for mass production was built in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1863.[1]

The company

Singer's original design, which was the first practical sewing machine for general domestic use, incorporated the basic eye-pointed needle and lock stitch developed by Elias Howe, who won a patent-infringement suit against Singer in 1854.

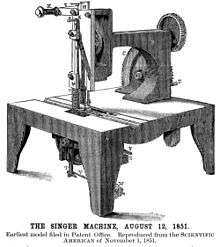

Patent No. 8294, of August 12, 1851, introduced one of the most useful machines, and one of the most remarkable men, that have figured in the development of the sewing machine. Isaac Merritt Singer, strolling player, theater manager, inventor, and millionaire, brought into the business a new machine and novel methods of exploitation, which gave a powerful impulse to the youthful industry. The Singer improvements met the demand of the tailoring, and leather industries for a heavier and more powerful machine.[2]

Singer consolidated enough patents in the field to enable him to engage in mass production, and by 1860, his company was the largest manufacturer of sewing machines in the world. In 1885, Singer produced its first "vibrating shuttle" sewing machine, an improvement over contemporary transverse shuttle designs; (see bobbin drivers). Singer began to market its machines internationally in 1855 and won first prize at the Paris World's Fair. The company demonstrated the first workable electric sewing machine at the Philadelphia electric exhibition in 1889 and began mass-producing domestic electric machines in 1910. Singer was also a marketing innovator and was a pioneer in promoting the use of installment payment plans.

Early sales figures

Source:[3]

| Year | 1853 | 1859 | 1867 | 1871 | 1873 | 1878 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Units | 810 | 10,953 | 43,053 | 181,260 | 232,444 | 262,316 |

By 1876, Singer was claiming cumulative sales of 2 million machines and displaying the 2 millionth in Philadelphia.[4]

Singer in Scotland

In 1867, the Singer Company decided that the demand for their sewing machines in the UK was sufficiently high to open a local factory in Glasgow on John Street. Glasgow was selected for its iron making industries, cheap labour and possibly because at the time the General Manager of the US Singer Manufacturing Company was George McKenzie, who was of Scottish descent. Demand for sewing machines outstripped production at the new plant and by 1873, a new larger factory was completed on James Street, Bridgeton. By now, Singer employed over 2,000 people in Scotland, but they still could not produce enough machines.

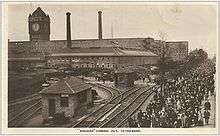

In 1882, George McKenzie, now President-elect of the Singer Manufacturing Company, undertook the ground breaking ceremony on 46 acres of farmland at Kilbowie, Clydebank. Originally, two main buildings were constructed, each 800-foot (240 m) long, 50-foot (15 m) wide and 3 storeys high. These were connected by three wings. Built above the middle wing was a huge 200-foot (61 m) tall clock tower with the 'Singer' name clearly displayed for all to see for miles around. 2.75 miles (4.43 km) of railway lines were laid throughout the factory to connect the different departments such as the boiler room, foundry, shipping and the lines to main railway stations. Sir Robert McAlpine was the building contractor and the factory was designed to be fire proof with water sprinklers, making it the most modern factory in Europe at that time.[5]

With nearly a million square feet of space and almost 7,000 employees, it was possible to produce on average 13,000 machines a week, making it the largest sewing machine factory in the world. The Clydebank factory was so productive that in 1905, the US Singer Company set up the Singer Manufacturing Company Ltd. as a UK registered company. Demand continued to exceed production, so each building was extended upwards to 6 storeys high.

In the First World War, sewing machine production gave way to munitions. The Singer Clydebank factory received over 5000 government contracts, and made 303 million artillery shells, shell components, fuses, and aeroplane parts, as well as grenades, rifle parts, and 361,000 horseshoes. Its labour force of 14,000 was about 70% female at war's end.[6]

From its opening in 1884 until 1943, the Kilbowie factory produced approximately 36,000,000 sewing machines. Singer was the world leader and sold more machines than all the other makers added together. In 1913, the factory shipped 1.3 million machines. The late 1950s and 1960s saw a period of significant change at the Clydebank factory. In 1958, Singer reduced production at their main American plant and transferred 40% of this production to the Clydebank factory in a bid to reduce costs. Between 1961 and 1964, the Clydebank factory underwent a £4 million modernization program which saw the Clydebank factory cease the production of cast iron machines and focus on the production of aluminium machines for western markets. As part of this modernisation programme, the famous Singer Clock was demolished in 1963. At the height of its productiveness in the mid 1960s, Singer employed over 16,000 workers but by the end of that decade, compulsory redundancies were taking place and 10 years later the workforce was down to 5,000. Financial problems and lack of orders forced the world's largest sewing machine factory to close in June 1980, bringing to an end over 100 years of sewing machine production in Scotland. The complex of buildings was demolished in 1998.[7]

World War II

During World War II, the company suspended sewing machine production to take on government contracts for weapons manufacturing. Factories in the US supplied the American forces with Norden bomb sights and M1 Carbine rifle receivers, while factories in Germany provided their armed forces with weapons.[8]

In 1939, the company was given a production study by the government to draw plans and develop standard raw material sizes for building M1911A1 pistols. The following April 17, Singer was given an educational order of 500 units with serial numbers S800001 – S800500. The educational order was a program set up by the US Ordnance Board to teach companies without gun-making experience to manufacture weapons.

After the 500 units were delivered to the government, the management decided to produce artillery and bomb sights. The pistol tooling and manufacturing machines were transferred to Remington Rand whilst some went to the Ithaca Gun Company. Approximately 1.75 million 1911A1's were produced during World War II, making original Singer pistols rare and collectable. In excellent condition, they can sell for $25,000 to $60,000 with the highest paid $166,750 at auction in 2010, conducted by Rock Island Auction Company.[9]

Marketing

The Singer sewing machine was the first complex standardized technology to be mass marketed. It was not the first sewing machine, and its patent in 1851 led to a patent battle with Elias Howe, inventor of the lockstitch machine. This eventually resulted in a patent sharing accord among the major firms.[10] Marketing strategies included focusing on the manufacturing industry,[11] gender identity,[12] credit plans,[13] and "hire purchases."[10]

Singer's marketing emphasized the role of women and their relationship to the home, evoking ideals of virtue, modesty, and diligence.[14] Though the sewing machine represented liberation from arduous hand sewing, it chiefly benefited those sewing for their families and themselves. Tradespeople relying on sewing as a livelihood still suffered from poor wages, which dropped further in response to the time savings gained by machine sewing.[10] Singer offered credit purchases and rent-to-own arrangements, allowing people to rent a machine with the rental payments applied to the eventual purchase of the machine,[10] and sold globally through the use of direct-sales door-to-door canvassers to demonstrate and sell the machines.[15]

Diversification

In the 1960s the company diversified, acquiring the Friden calculator company in 1965, Packard Bell Electronics in 1966 and General Precision Equipment Corporation in 1968. GPE included Librascope, The Kearfott Company, Inc, and Link Flight Simulation. In the 1968 also Singer bought out GPS Systems and added it to the Link Simulations Systems Division (LSSD). This unit produced nuclear power plant control center simulators in Silver Spring, MD and Columbia, MD, while flight simulators were produced in Binghamton, New York.

In 1987, corporate raider Paul Bilzerian made a "greenmail" run at Singer, and ended up owning the company when no "White Knight" rescuer appeared. To recover his money, Bilzerian sold off parts of the company. Kearfott was split, the Kearfott Guidance & Navigation Corporation was sold to the Astronautics Corporation of America in 1988 and the Electronic Systems Division was purchased by GEC-Marconi in 1990, renamed GEC-Marconi Electronic Systems (and later incorporated into BAE Systems). The four Link divisions developing and supporting industrial and flight simulation were sold to Canadian Avionics Electronics (CAE) and became CAE-Link. The nuclear power simulator division became S3 Technologies, and later GSE Systems, and relocated to Eldersburg, MD. The Sewing Machine Division was sold in 1989 to Semi-Tech Microelectronics, a publicly traded Toronto-based company.[16]

For several years in the 1970s, Singer set up a national sales force for CAT phototypesetting machines (of UNIX troff fame) made by another Massachusetts company, Graphic Systems Inc.[17] This division was purchased by Wang Laboratories in 1978.

21st century

The Singer Corporation produces a range of consumer products, including electronic sewing machines. It is now part of SVP Worldwide, which also owns the Pfaff and Husqvarna Viking brands, which is in turn owned by Kohlberg & Company, which bought Singer in 2004. Its main competitors are Brother Industries, Janome, Aisin Seiki—a Toyota Group company that manufactures Toyota, Necchi and E&R Classic Sewing Machines and Juki.

Singer Buildings

Singer was heavily involved in Manhattan real estate in the 1800s through Edward Clark, a founder of the company. Clark had built The Dakota apartments and other Manhattan buildings in the 1880s. In 1900, the Singer company retained Ernest Flagg to build a 12-story loft building at Broadway and Prince Street in Lower Manhattan. The building is now considered architecturally notable, and has been restored.[18]

The 47-story Singer Building, completed in 1908, was also designed by Flagg, who designed two landmark residences for Bourne. Constructed during Bourne's tenure, the Singer Building (demolished in 1968) was then the tallest building in the world and was the tallest building to be intentionally demolished until the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center were destroyed in the September 11 attacks.[19]

At their Clydebank Scotland factory Singer built a 200 ft clock tower which stood over the central wing and had the reputation of being the largest four-faced clock in the world. Each face weighed five tons and it took four men fifteen minutes twice a week to keep it wound.[20] The tower was demolished after the factory closed in 1980 and now site of Clydebank Business Park. Singer railway station, built to serve the factory, is still in existence to this day.

The famous Singer House, designed by architect Pavel Suzor, was built in 1902–1904 at Nevsky Prospekt in Saint Petersburg for headquarters of the Russian branch of the company. This modern style building (situated just opposite to the Kazan Cathedral) is officially recognized as an object of Russian historical-cultural heritage.

Brand Ambassadors

In January 2018, Singer appointed Mike Aspinall from The Crafty Gentleman blog as its first UK Brand Ambassador.[21] Mike has been running his craft blog since 2013 and has over 10 years of sewing experience. He has been named the 5th most popular UK DIY blogger[22] and the 17th most popular UK craft blogger,[23] and has appeared on Channel 4 and the BBC to promote crafts for men.[24] As part of his role as Singer Brand Ambassador, he shares regular craft tutorials and projects on his blog and social media channels.

List of company presidents

- Isaac Singer (1851–1863)

- Inslee Hopper (1863–1875)

- Edward C. Clark (1875–1882)

- George Ross McKenzie (1882–1889)

- Frederick Gilbert Bourne (1889–1905)

- Sir Douglas Alexander (1905–1949)

- Milton C. Lightner (1949–1958)

- Donald P. Kircher (1958–1975)

- Joseph Bernard Flavin (1975–1987)

- Paul Bilzerian (1987–1989)[25]

- Iftikhar Ahmed (1989–1997)[26]

- Stephen H. Goodman (1998–2004)

Four of the more popular domestic Singer sewing machines

A Singer model 12K fiddle-bed from 1878.

A Singer model 12K fiddle-bed from 1878.- A Singer model 66 with Lotus decals from 1922.

A Singer model 99 from 1939.

A Singer model 99 from 1939. A Singer Featherweight model 222k from 1954.

A Singer Featherweight model 222k from 1954.

See also

References

- ↑ Cunningham, John T. (2004). Ellis Island: Immigration's Shining Center. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-2428-3.

- ↑ "Sewing machine history". Archived from the original on 2010-03-28.

- ↑ "Sewing Machines". Machine-History.Com. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved 2012-09-03.

- ↑ Fort Moultrie Centennial, Part II. Charleston: Walker, Evans & Cogswell. 1876. p. 29. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ "A portrait of achievement" (PDF). Sir Robert McAlpine. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ↑ Robert Bruce Davies, Peacefully working to conquer the world (Arno Press, 1976) p 170

- ↑ "Singer Sewing Machine Factory Kilbowie, Clydebank".

- ↑ Sanders, Richard Robert S. Clark (1877-1956), Press for Conversion! magazine, Issue # 53, "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism," March 2004. Published by the Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade.

- ↑ Singer Manufacturing Co. 1941 1911A1, From the Karl Karash collection/Images Copyright Karl Karash 2002

- 1 2 3 4 Joan Perkin, "Sewing Machines: Liberation or Drudgery for Women?" History Today 52 (Dec. 2002).

- ↑ Andrew Godley "Selling the Sewing Machine Around the World: Singers International Marketing Strategies, 1850-1920." Enterprise and Society (June 2007) 7 281.

- ↑ Judith G. Coffin, "Credit, Consumption, and Images of Women's Desires: Selling the Sewing Machine in Late Nineteenth-Century France." Historical Studies (Spring, 1994) 18 746-750.

- ↑ Judith G. Coffin, "Credit, Consumption, and Images of Women's Desires: Selling the Sewing Machine in Late Nineteenth-Century France." Historical Studies (Spring, 1994) 18 752

- ↑ Judith G. Coffin, "Credit, Consumption, and Images of Women's Desires: Selling the Sewing Machine in Late Nineteenth-Century France." Historical Studies (Spring, 1994) 18 746-752.

- ↑ Andrew Godley "Selling the Sewing Machine Around the World: Singers International Marketing Strategies, 1850-1920." Enterprise and Society (June 2007) 7 269-281.

- ↑ Miller, Matthew; Clifford, Mark L.; Zegel, Susan (5 August 2002). "Dishonored Dealmaker". Businessweek. Retrieved 2007-03-25.

- ↑ "Old Phototypesetter Tales". Haagens.com.

- ↑ Gray, Christopher (29 June 1997). "Style Standard for Early Steel-Framed Skyscraper". The New York Times. p. 7. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ↑ "New York Architecture Images- HOME". nyc-architecture.com.

- ↑ "Singer Clydebank history on West Dunbarton Council website".

- ↑ "I'm a Singer Brand Ambassador | The Crafty Gentleman". The Crafty Gentleman. 2018-01-20. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ↑ "Top 30 DIY Blogs UK | DIY Websites UK". blog.feedspot.com. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ↑ "Top 50 Craft Blogs UK | Craft Websites UK". blog.feedspot.com. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ↑ "Press | The Crafty Gentleman". The Crafty Gentleman. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- ↑ "A Raider's Days Of Reckoning". Time Magazine. 10 July 1989. Retrieved 2007-05-01.

- ↑ Daniel Hilken & Albert Wong (July 1, 2005). "Semi-Tech's Ting jailed six years". The Standard (Hong Kong). Retrieved 2010-08-15.

Further reading

- Brandon, Ruth. A capitalist romance: Singer and the sewing machine (Lippincott, 1977).

- Coffin, Judith G. "Credit, consumption, and images of women's desires: selling the sewing machine in late nineteenth-century France." French Historical Studies (1994): 749-783. in JSTOR

- Davies, Robert Bruce. Peacefully working to conquer the world: Singer sewing machines in foreign markets, 1854-1920 (Arno Press, 1976).

- Godley, Andrew. "The Global Diffusion of the Sewing Machine, 1850-1914." Research in Economic history 20#1 (2001): 1-46.

- Godley, Andrew. "Selling the Sewing Machine Around the World: Singer's International Marketing Strategies, 1850—1920," Enterprise & Society (2006) 7#2 pp. 266–314 in JSTOR

- Godley, Andrew. "Singer in Britain: the diffusion of sewing machine technology and its impact on the clothing industry in the United Kingdom, 1860–1905." Textile history 27.1 (1996): 59-76.

- Jack, Andrew B. "The channels of distribution for an innovation: The sewing-machine industry in America, 1860-1865." Explorations in Economic History 9.3 (1957): 113.

- Weber, Nicholas Fox. The Clarks of Cooperstown: Their Singer Sewing Machine Fortune, Their Great and Influential Art Collections, Their Forty-year Feud (Alfred A. Knopf, 2007).

- Wickramasinghe, Nira. "Following the Singer Sewing Machine: Fashioning a Market in a British Crown Colony" in Metallic Modern: Everyday Machines in Colonial Sri Lanka. (Berghahn Books, 2014) pp. 16–40. in JSTOR

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Singer Corporation. |

- Singer Corporation Official website

- Singer Corporation Worldwide Official website

- Singer Memories: company story

- Singer Direct Singer history timeline

- Singer in WWII Singer's contribution to the war effort

- Singer sewing machine serial numbers and dates

- Toyota Sewing Machines Japan Official website

- Toyota Sewing Machines Europe Official website

- Sewing Machines, Historical Trade Literature Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- Singer Sewing company South Africa Singer Sewing Company South Africa

- Singer Manufacturing company records at Newberry Library

- Singer Sewing Machines E-Tailer Website

- Singer Company records (1851–1990) at Hagley Museum and Library

- Singer Manufacturing Company Records (1860–1878) at Hagley Museum and Library

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NJ-51, "Singer Manufacturing Company, 321 First Street, Elizabeth, Union County, NJ"