Dreadlocks

Dreadlocks, also locs, dreads, or in Sanskrit, Jaṭā,[1] are ropelike strands of hair formed by matting or braiding hair.[2] Earliest depictions of dreadlocks date from over 2000 years ago.[3]

Origins

The ancient Vedic scriptures of India which are thousands of years old have the earliest evidence of jaata/locks which are almost exclusively worn by holy men and women. It has been part of a religious practice for Shiva followers.

Some of the earliest depictions of dreadlocks date back as far as 3600 years to the Minoan Civilization, one of Europe's earliest civilizations, centred in Crete (now part of Greece).[3] Frescoes discovered on the Aegean island of Thera (modern Santorini, Greece) depict individuals with braided hair styled in long dreadlocks.[7][3]

In ancient Egypt, examples of Egyptians wearing locked hairstyles and wigs have appeared on bas-reliefs, statuary and other artifacts.[8] Mummified remains of ancient Egyptians with locked wigs have also been recovered from archaeological sites.[9]

During the Bronze Age and Iron Age, many peoples in the Near East, Asia Minor, Caucasus, East Mediterranean and North Africa such as the Sumerians, Elamites, Ancient Egyptians, Ancient Greeks, Akkadians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Hittites, Amorites, Mitanni, Hattians, Hurrians, Arameans, Eblaites, Israelites, Phrygians, Lydians, Persians, Medes, Parthians, Chaldeans, Armenians, Georgians, Cilicians and Canaanites/Phoenicians/Carthaginians are depicted in art with braided or plaited hair and beards.[10][11]

History

In Ancient Greece, kouros sculptures from the archaic period depict men wearing dreadlocks[12][13] while Spartan hoplites[14] wore formal locks as part of their battle dress.[15] Spartan magistrates known as Ephors also wore their hair braided in long locks, an Archaic Greek tradition that was steadily abandoned in other Greek kingdoms.[16]

The style was worn by Ancient Christian Ascetics in the Middle East and Mediterranean, and the Dervishes of Islam, among others.[17] Some of the very earliest adherents of Christianity in the Middle East may have worn this hairstyle; there are descriptions of James the Just, first Bishop of Jerusalem, who is said to have worn them to his ankles.[18]

Pre-Columbian Aztec priests were described in Aztec codices (including the Durán Codex, the Codex Tudela and the Codex Mendoza) as wearing their hair untouched, allowing it to grow long and matted.[19] Bernal Diaz del Castillo records:

here were priests with long robes of black cloth... The hair of these priests was very long and so matted that it could not be separated or disentangled, and most of them had their ears scarified, and their hair was clotted with blood.

In Senegal, the Baye Fall, followers of the Mouride movement, a Sufi movement of Islam founded in 1887 AD by Shaykh Aamadu Bàmba Mbàkke, are famous for growing locks and wearing multi-colored gowns.[20] Cheikh Ibra Fall, founder of the Baye Fall school of the Mouride Brotherhood, popularized the style by adding a mystic touch to it. Warriors among the Fulani, Wolof and Serer in Mauritania, and Mandinka in Mali and Niger were known for centuries to have worn cornrows when young and dreadlocks when old.

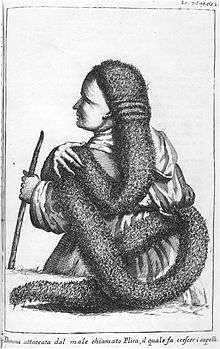

Larry Wolff in his book Inventing Eastern Europe: The Map of Civilization on the Mind of Enlightenment mentions that in Poland, for about a thousand years, some people wore the hair style of the Scythians. Zygmunt Gloger in his Encyklopedia staropolska mentions that Polish plait (dreadlocks or plica polonica) was worn as a hair style by some people of both genders in the Pinsk region and the Masovia region at the beginning of the 19th century. Gloger argued that according to research done by the Grimm Brothers and Rosenbaum, plica polonica and the idea that it spread from Poland was an error, as it was also found among the Germanic population of Bavaria and Rhine River area. He said that the word "Weichselzopf" (Vistula plait) was a later alteration of the name "Wichtelzopf", "plait of a Wichtel"; "Wichtel" means wight in German, a being or sentient thing.

By culture

Locks have been worn for various reasons in each culture: as an expression of deep religious or spiritual convictions, ethnic pride, as a political statement and in more modern times, as a representation of a free, alternative or natural spirit.[21] Their use has also been raised in debates about cultural appropriation.[22]

Africa

Members of various African ethnic groups wear locks and the styles and significance may differ from one group to another.

Maasai warriors are famous for their long, thin, red locks. Many people dye their hair red with root extracts or red ochre. In various cultures what are known as shamans, spiritual men or women who serve and speak to spirits or deities, often wear locks. In Nigeria,[23] some children are born with naturally locked hair and are given a special name: "Dada". Yoruba priests of Olokun, the Orisha of the deep ocean, wear locks. Another group is the Turkana people of Kenya. In Ghana, the Akan refer to dreadlocks as Mpɛsɛ, which is the hairstyle of Akomfoɔ or priests and even common people. Along with the Asante-Akan drums known as Kete drums, this hairstyle was later adopted by Rastas, with its roots in Jamaica from the slave trade era.

Australia

Historically, many indigenous Australians of North West and North Central Australia wore their hair in a locked style, sometimes also having long beards that were fully or partially locked. Some wore the locks loose, while others wrapped the locks around their heads, or bound them at the back of the head.[24] In North Central Australia, the locks were often greased with fat and coated with red ochre, which assisted in their formation. [25]

Hinduism

Hindu Vedic scriptures provide the earliest known evidence of dreadlocks. Locks are worn in India by Sadhus or Holy men. The Nagas are ascetics and followers of the god Shiva. They wear their Jaata (locks) above their head and let them down only for special occasions and rituals. Jaata means twisted locks of hair. Indian holy men and women regard locks as sacred, considered to be a religious practice and an expression for their disregard of vanity.

Buddhism

Within Tibetan Buddhism and other more esoteric forms of Buddhism, dreadlocks have occasionally been substituted for the more traditional shaved head. The most recognizable of these groups are known as the Ngagpas of Tibet. For many practicing Buddhists, dreadlocks are a way to let go of material vanity and excessive attachments.[26] Dreadlocks were required for many esoteric Buddhist rituals in medieval South Asia performed by Buddhist yogis (Buddhist counterparts to contemporary Hindu sadhus). For instance, 1.4.15 of the Hevajratantra states that the practitioner "should arrange his piled up hair".[27] In contemporary Tibetan practice matted hair is replaced by crowns with matted hair attached to them.

Rastafari

Rastafari movement locks are symbolic of the Lion of Judah which is sometimes centered on the Ethiopian flag. Rastafari hold that Haile Selassie is a direct descendant of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba, through their son Menelik I. Their dreadlocks were inspired by the Nazarites of the Bible.[28]

Much like the adoption of grandiose names by individuals and organisations, the cultivation of dreadlocks in the later Rastafari movement established a closer connection between the movement and the ideology it espoused. It also gave the appearance, if not the substance, of greater authority.[29]

When reggae music gained popularity and mainstream acceptance in the 1970s thanks to Bob Marley's music and cultural influence, the locks (often called "dreads") became a notable fashion statement worldwide; they have been worn by prominent authors, actors, athletes and rappers.

In sports

Dreadlocks have become a popular hairstyle among professional athletes, ranging from Larry Fitzgerald's dreads down to his back to Drew Gooden's facial dreadlocks.

In professional American football, the number of players with dreadlocks has increased ever since Al Harris and Ricky Williams first wore the style during the 1990s. In 2012, about 180 National Football League players wore dreadlocks. A significant number of these players are defensive backs, who are less likely to be tackled than offensive players.[30] Players with very long dreadlocks have been tackled by their hair, which is legal according to NFL rules.

In the NBA there has been controversy over the Brooklyn Nets guard, Jeremy Lin. Lin, an Asian-American, garnered mild controversy over his choice of dreadlocks. Former NBA player Kenyon Martin accused Lin of appropriating African-American culture in a since-deleted social media post. [31]

In western fashion

African Americans as well as non-American blacks have developed a large variety of ways to wear dreadlocked hair. Specific elements of these styles include the flat-twist, in which a section of locks are rolled together flat against the scalp to create an effect similar to the cornrows, and braided dreadlocks. Examples include flat-twisted half-back styles, flat-twisted mohawk styles, braided buns and braid-outs (or lock crinkles).

Locked models have appeared at fashion shows, and Rasta clothing with a Jamaican-style reggae look was sold. Even exclusive fashion brands like Christian Dior created whole Rasta-inspired collections worn by models with a variety of lock hairstyles.

With dreadlocks style in vogue, the fashion and beauty industries capitalized on the trend. A completely new line of hair care products and services in salons catered to a white clientele, offering all sorts of dreadlocks hair care items such as wax (considered unnecessary and even harmful by many),[32] shampoo, and jewelry. Hairstylists created a wide variety of modified locks, including multi-colored synthetic lock hair extensions and "dread perms", where chemicals are used to treat the hair.

In Western counterculture

In the West, since gatherings of hippies became common in the 1970s, dreadlocks have gained particular popularity among predominantly caucasian, counterculture adherents such as hippies, crust punks, New Age travellers, goths and many members of the Rainbow Family.[33] Many people from these cultures wear dreadlocks for similar reasons: symbolizing a rejection of government-controlled, mass-merchandising culture or to fit in with the people and crowd they want to be a part of (such as those who are fans of reggae music). Members of the cybergoth subculture also often wear blatantly artificial synthetic dreads or "dreadfalls" made of synthetic hair, fabric or plastic tubing.[34]

Methods of making dreadlocks

Traditionally, it was believed that in order to create dreadlocks in non afro-textured hair, an individual had to refrain from brushing, combing or cutting. This lack of hair grooming results in what is called "free form" or "neglect" dreads, where the hair matts together slowly of its own accord. Such dreads tend to vary greatly in size, width, shape, length, and texture. If the wearer is interested in any uniformity of their dreads, they must pull the matted strands of hair apart to ensure large clumps don't form. All that is needed alongside the regular separating of sections is regular washing; oily dirty hair will slide along each other and never form knots. Some people will spray a water solution with added sea salt and essential oils to dry the hair and accelerate the matting process.

A variety of other starter methods have been developed to offer greater control over the general appearance of dreadlocks. They can be formed through a technique called "twist and rip", as well as backcombing and rolling.[35]Together, these alternative techniques are more commonly referred to as "salon" or "manicured" dreadlocks.[36]

Using beeswax to make dreads can cause problems because it does not wash out, due to the high melting point of natural wax. Because wax is a hydrocarbon, water alone, no matter how hot, will not be able to remove wax.[37]This is often where problems like mold and dread rot come from, the wax clogs inside the length of the dread meaning water can't run out easily. Having wet dreads for long periods of time helps mildew set in, this combined with the wax and every dirt/dust/fluff particle that has stuck to the wax can result in moldy, slimy dreads.

As with the organic and freeform method, the salon methods rely on hair naturally matting over a period of months to gradually form dreadlocks. The difference is in the initial technique by which loose hair is encouraged to form a rope-like shape. Whereas freeform dreadlocks can be created by simply refraining from combing or brushing hair and occasionally separating matted sections, salon dreadlocks use tool techniques to form the basis of the starter, immature set of dreadlocks. A "matured" set of salon dreadlocks won't look the same as a set of dreadlocks that have been started with neglect or freeform.

For African hair types, salon dreadlocks can be formed by evenly sectioning and styling the loose hair into braids, coils, twists, or using a procedure called dread perming specifically used for straight hair. For European, Indigenous American, Asian, and Indian hair types, Backcombing and Twist and Rip[35]are some of the more popular methods of achieving starter dreadlocks.

Regardless of hair type or texture and starter method used, dreadlocks require time before they are fully matured. The process hair goes through as it develops into matured dreadlocks is continuous.

There is also the ability to adopt different types of fake dreadlocks that may make the hair look as real as possible. This process is called synthetic dreadlocks. There are two different types of synthetic dreadlocks. The first is dread extensions, in which other hair can be infused with the wearer's own hair. The second is dreadfalls, in which one dread is tied into another with either elastic or lace. Both of these methods are used to make dreads look better and more appealing, and to achieve the desired effect of longer hair.

Guinness Book of World Records

On December 10, 2010, the Guinness Book of World Records rested its "longest dreadlocks" category after investigation of its first and only female title holder, Asha Mandela, with this official statement:

Following a review of our guidelines for the longest dreadlock, we have taken expert advice and made the decision to rest this category. The reason for this is that it is difficult, and in many cases impossible, to measure the authenticity of the locks due to expert methods employed in the attachment of hair extensions/re-attachment of broken off dreadlocks. Effectively the dreadlock can become an extension and therefore impossible to adjudicate accurately. It is for this reason Guinness World Records has decided to rest the category and will no longer be monitoring the category for longest dreadlock.[38]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Hair: Styling, Culture and Fashion. University of Michigan [Michigan]: Bloomsbury Academic. 2009. ISBN 9781845207922.

His jata (dreadlocks) are elegantly styled, and the source of the Ganges issues from his topknot. In the background are the Himalayas where Shiva performs his austerities.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster (2004). Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary: Eleventh Edition. [ ]: Merriam-Webster. p. 380. ISBN 9780877798095.

dread-lock \'dred-,lak\ n (I960) 1 : a narrow ropelike strand of hair formed by matting or braiding 2 pi : a hairstyle consisting of dreadlocks — dread-locked \-,lakt\ adj

- 1 2 3 BLENCOWE, CHRIS (2013). YRIA: The Guiding Shadow. Sidewalk Editions. p. 36. ISBN 9780992676100.

... Archaeologist Christos Doumas, discoverer of Akrotiri, wrote: “Even though the character of the wall-paintings from Thera is Minoan, ... the boxing children with dreadlocks, and ochre-coloured naked fishermen proudly displaying their abundant hauls of blue and yellow fish.

- ↑ Poliakoff, Michael B. (1987). Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture. Yale University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780300063127.

The boxing boys on a fresco from Thera (now the Greek island of Santorini), also 1500 B.C.E., are less martial with their jewelry and long braids, and it is hard to imagine that they are engaged in a hazardous

- ↑ BLENCOWE, CHRIS (2013). YRIA: The Guiding Shadow. Sidewalk Editions. p. 36. ISBN 9780992676100.

... Archaeologist Christos Doumas, discoverer of Akrotiri, wrote: “Even though the character of the wall-paintings from Thera is Minoan, ... the boxing children with dreadlocks, and ochre-coloured naked fishermen proudly displaying their abundant hauls of blue and yellow fish.

- ↑ Bloomer, W. Martin (2015). A Companion to Ancient Education. John Wiley & Sons. p. 31. ISBN 9781119023890.

Figure 2.1b Two Minoan boys with distinctive hairstyles, boxing. Fresco from West House, Thera (Santorini), ca. 1600–1500 bce (now in the National Museum, Athens).

- ↑ Poliakoff, Michael B. (1987). Combat Sports in the Ancient World: Competition, Violence, and Culture. Yale University Press. p. 172. ISBN 9780300063127.

The boxing boys on a fresco from Thera (now the Greek island of Santorini), also 1500 B.C.E., are less martial with their jewelry and long braids, and it is hard to imagine that they are engaged in a hazardous

- ↑ "Image of Egyptian with locks". freemaninstitute.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ Egyptian Museum -"Return of the Mummy. Archived 2005-12-30 at the Wayback Machine. Toronto Life - 2002." Retrieved 01-26-2007.

- ↑ http://www.ukhairdressers.com/history%20of%20hair.asp

- ↑ "plaits". www.ancient-origins.net. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- 1 2 Steves, Rick (2014). Athens and the Peloponnese. Avalon Travel. p. 165. ISBN 1-61238-060-3.

- ↑ Jenkins, Ian. Archaic Kouroi in Naucratis: The Case for Cypriot Origin. [JSTOR Arts & Sciences II Collection]: American Journal of Archaeology, v105 n2 (20010401):. pp. 168–175. ISSN 0002-9114.

The hair in both is filleted into a series of fine dreadlocks, tucked behind the ears and falling on each shoulder and down the back. A narrow fillet passes around the forehead and disappears behind the ears. … Two are in the British Museum (fig. 17) and another in Boston (fig. 18). These three could have been carved by the same hand. Distinctive points of comparison include the dreadlocks; high, prominent chest without division; sloping shoulders; manner of showing the arms by the side…the torso of a kouros, again in Boston (fig. 19), should probably also be assigned to this group.

- ↑ Myres, Sir John Linton. Who Were the Greeks?. Sather Lectures. University of California Press. p. 195. ISSN 0080-6684.

- ↑ Hook, Richard (1998). The Spartan Army. Osprey Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 1-85532-659-0.

- ↑ Sekunda, Nick (2002). Marathon 490 BC: The First Persian Invasion of Greece. Osprey Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-1-84176-000-1.

The ephors were members of the 'Spartiate' class who were noted for the uniformity of their dress, and their archaic hairstyles. They continued to wear long hair, a fashion long dead elsewhere among Greek aristocrats. The hair was braided into long locks all gathered together at the back, sometimes with a couple of locks allowed to fall lose.

- ↑ Thompson, John; Patrick, Bethanne (2015). An Uncommon History of Common Things. National Geographic Books. p. 165. ISBN 1-4262-1227-5.

- ↑ Glazier, Stephen D., Encyclopedia of African and African-American Religions, Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0-415-92245-3, ISBN 978-0-415-92245-6, p. 279.

- ↑ Berdán, Frances F. and Rieff Anawalt, Patricia (1997). The Essential Codex Mendoza. London, England: University of California Press. pp 149.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-27. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ "The diverse cultural & personal meanings dreads have for their owners..." 2016-04-04. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ↑ "Students are claiming the white man harassed over his dreadlocks isn't telling the full story". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-07-18.

- ↑ "Dada or dreds – Neologisms".

- ↑ Withnell, John G. (1901). The Customs And Traditions Of The Aboriginal Natives Of North Western Australia. ROEBOURNE. p. 14.

- ↑ Baldwin Spencer and F. J. Gillen (1899). The Native Tribes of North Central Australia. London: Macmillan.

- ↑ The Dreadlocks Treatise: On Tantric Hairstyles in Tibetan Buddhism.

- ↑ Snellgrove, David. The Hevajra Tantra: A Critical Study. vol 1. Oxford University Press. 1959.

- ↑ Chevannes, Barry (1994). RASTAFARI: ROOTS AND IDEOLOGY. Syracuse University Press. p. 158. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ↑ Charet, M. (2010). Root of David: The Symbolic Origins of Rastafari (No. 2). ISPCK.

- ↑ "Matz: NFL players embracing long hair". ESPN.com. 29 December 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ https://www.cbssports.com/nba/news/jeremy-lin-hair-dreadlocks-kenyon-martin-lil-b-curse-nets/

- ↑ "Fromgrandmaskitchen.com". fromgrandmaskitchen.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ "Hippies with Dreadlocks and why I quit Reggae". Grave Error. 2006-08-01. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ↑ Cherish Marasigan (2018-06-14). "Intro To Cyber Goth: Goth'S Futuristic Side". Rebels Market. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- 1 2 Lazy Dreads (2014-03-21), TWIST & RIP DREADLOCKS INFORMATION!, retrieved 2017-01-22

- ↑ "Fromgrandmaskitchen.com". fromgrandmaskitchen.com. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2013-06-09.

- ↑ "Longest Dreadlock Record – Rested". Archived from the original on 2011-10-05.

References

- Kroemer, K. (2001). Ergonomics: How to Design for Ease and Efficiency (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0137524781.

- Tacitus, Publius (or Gaius) Cornelius (A.D. 98). De vita et moribus Iulii Agricolae. Check date values in:

|year=(help)

External links

| Look up dreadlocks or dreadlock in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dreadlocks. |