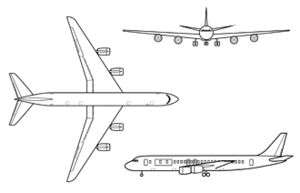

Douglas DC-8

| DC-8 | |

|---|---|

| |

| An Air Jamaica DC-8-62H approaching London Heathrow Airport in 1978 | |

| Role | Narrow-body jet airliner |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company (1958-1967) McDonnell Douglas (1967-1972) |

| First flight | May 30, 1958 |

| Introduction | September 18, 1959, with Delta Air Lines and United Airlines |

| Status | In limited service as cargo aircraft |

| Primary users | United Airlines (historical) UPS Airlines (historical) Delta Air Lines (historical) CFS Air Cargo |

| Produced | 1958–1972 |

| Number built | 556 |

The Douglas DC-8 (also known as the McDonnell Douglas DC-8) is an American four-engine mid- to long-range narrow-body jet airliner built from 1958 to 1972 by the Douglas Aircraft Company. Launched after the competing Boeing 707, the DC-8 nevertheless kept Douglas in a strong position in the airliner market, and remained in production until 1972 when it began to be superseded by larger wide-body designs, including the Boeing 747, McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and Lockheed L-1011 TriStar. The DC-8's design allowed it a slightly larger cargo capacity than the 707 and some re-engined DC-8s are still in use as freighters.

Development

Background

After World War II Douglas had a commanding position in the commercial aviation market. Boeing had pointed the way to the modern all-metal airliner in 1933 with its Model 247, but Douglas, more than any other company, made commercial air travel a reality. Douglas produced a succession of piston-engined aircraft (DC-2, DC-3, DC-4, DC-5, DC-6, and DC-7) through the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. When de Havilland flew the first jet airliner, the Comet, in 1949, Douglas felt no need to rush into anything new. Their U.S. competitors at Lockheed and Convair felt the same way: that there would be a gradual switch from piston engines to turbines, and that the switch would be to the more fuel-efficient turboprop engines rather than pure jets. All three companies were working on a new generation of piston-engined designs, with an eye to turboprop conversion in the future.

De Havilland's pioneering Comet entered airline service in 1952. Initially it was a success, but it was grounded after several fatal crashes in 1953 and 1954. The cause of the Comet crashes had nothing to do with jet engines; it was a rapid metal fatigue failure in corners of the near-square windows brought on from cycling cabin pressures in flight to high altitudes and back. The understanding of metal fatigue that the Comet investigation produced would play a vital part in the good safety record of later types like the DC-8. In 1952 Douglas remained the most successful of the commercial aircraft manufacturers. They had almost 300 orders on hand for the piston-engined DC-6 and its successor, the DC-7, which had yet to fly. The Comet disasters, and the airlines' subsequent lack of interest in jets, seemed to show the wisdom of their staying with propeller-driven aircraft.

Competition

Boeing took the bold step of starting to plan a pure-jet airliner as early as 1949. Boeing's military arm had gained experience with large, long-range jets through the B-47 Stratojet (first flight 1947) and the B-52 Stratofortress (1952). With thousands of jet bombers on order or in service, Boeing had developed a close relationship with the US Air Force's Strategic Air Command (SAC). Boeing also supplied the SAC's refueling aircraft, the piston-engined KC-97 Stratofreighters, but these were too slow and low flying to easily work with the new jet bombers. The B-52, in particular, had to descend from its cruising altitude and then slow almost to stall speed to work with the KC-97.

Believing that a requirement for a jet-powered tanker was a certainty, Boeing started work on a new jet aircraft for this role that could be adapted into an airliner. As an airliner it would have similar seating capacity to the Comet, but its swept wing would give it higher cruising speed and better range. First presented in 1950 as the Model 473-60C, Boeing failed to generate any interest at the airlines. Boeing remained convinced that the project was worthwhile, and decided to press ahead with a prototype, the Boeing 367-80 ("Dash-80"). After spending $16 million of their own money on construction, the Dash-80 rolled out on May 15, 1954, and flew the next month. Boeing's plans became obvious, despite the misleading older model number.

Early design phase

Douglas secretly began jet transport project definition studies in mid-1952. By mid-1953 these had developed into a form similar to the final DC-8; an 80-seat, low-wing aircraft with four Pratt & Whitney JT3C turbojet engines, 30° wing sweep, and an internal cabin diameter of 11 feet (3.35 m) to allow five-abreast seating. Maximum weight was to be 190,000 lb (86 metric tons), and range was estimated to be about 3,000–4,000 miles (4,800–6,400 km).

Douglas remained lukewarm about the jet airliner project, but believed that the Air Force tanker contract would go to two companies for two different aircraft, as several USAF transport contracts in the past had done. In May 1954, the USAF circulated its requirement for 800 jet tankers to Boeing, Douglas, Convair, Fairchild, Lockheed, and Martin. Boeing was just two months away from having their prototype in the air. Just four months after issuing the tanker requirement, the USAF ordered the first 29 KC-135s from Boeing. Besides Boeing's ability to provide a jet tanker promptly, the flying-boom air-to-air refueling system was also a Boeing product from the KC-97.

.jpg)

Donald Douglas was shocked by the rapidity of the decision which, he said, had been made before the competing companies even had time to complete their bids. He protested to Washington, but without success. Having started on the DC-8 project, Douglas decided that it was better to press on than give up. Consultations with the airlines resulted in a number of changes: the fuselage was widened by 15 inches (38 cm) to allow six-abreast seating. This led to larger wings and tail surfaces and a longer fuselage. The DC-8 was announced in July 1955. Four versions were offered to begin with, all with the same 150-foot-6-inch (45.87 m) long airframe with a 141-foot-1-inch (43.00 m) wingspan, but varying in engines and fuel capacity, and with maximum weights of about 240,000–260,000 lb (109–118 metric tons). Douglas steadfastly refused to offer different fuselage sizes. The maiden flight was planned for December 1957, with entry into revenue service in 1959. Well aware that they were lagging behind Boeing, Douglas began a major marketing push.

First orders

Douglas' previous thinking about the airliner market seemed to be coming true; the transition to turbine power looked likely to be to turboprops rather than turbojets. The pioneering 40–60-seat Vickers Viscount was in service and proving popular with passengers and airlines: it was faster, quieter and more comfortable than piston-engined types. Another British rival was the 90-seat Bristol Britannia, and Douglas's main rival in the large airliner market, Lockheed, had committed to the short/medium range 80–100-seat turboprop Electra, with a launch order from American Airlines for 35 and other orders flowing in. Meanwhile, the Comet remained grounded, the French 90-passenger twin jet Sud Aviation Caravelle prototype had just flown for the first time, and the 707 was not expected to be available until late 1958. The major airlines were reluctant to commit themselves to the huge financial and technical challenge of jet aircraft. However, no one could afford not to buy jets if their competitors did.

There the matter rested until October 1955, when Pan American World Airways placed simultaneous orders with Boeing for 20 707s and Douglas for 25 DC-8s. To buy one expensive and untried jet-powered aircraft type was brave: to buy both was, at the time, unheard of. In the closing months of 1955, other airlines rushed to follow suit: Air France, American Airlines, Braniff International Airways, Continental Airlines, and Sabena ordered 707s; United Airlines, National Airlines, KLM, Eastern Air Lines, Japan Air Lines, and Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) chose the DC-8. In 1956, Air India, BOAC, Lufthansa, Qantas, and TWA added over 50 to the 707 order book, while Douglas sold 22 DC-8s to Delta, Swissair, TAI, Trans Canada, and UAT. By the start of 1958, Douglas had sold 133 DC-8s compared to Boeing's 150 707s.

Basic price of a JT4 powered "domestic" version of the DC-8 was around US$5.46 million (£1.95 million) in 1960.[1]

Production and testing

Donald Douglas proposed to build and test the DC-8 at Santa Monica Airport, which had been the birthplace of the DC-3 and home to a Douglas plant that employed 44,000 workers during World War II. In order to accommodate the new jet, Douglas asked the city of Santa Monica, California to lengthen the airport's 5,000-foot runway. Following complaints by neighboring residents, the city refused, so Douglas moved its airliner production line to Long Beach Airport.[2] The first DC-8 N8008D was rolled out of the new Long Beach factory on 9 April 1958 and flew for the first time, in Series 10 form, on 30 May for two hours seven minutes with the crew being led by A.G. Heimerdinger.[3] Later that year an enlarged version of the Comet finally returned to service, but too late to take a substantial portion of the market: de Havilland had just 25 orders. In August Boeing had begun delivering 707s to Pan Am. Douglas made a massive effort to close the gap with Boeing, using no fewer than ten aircraft for flight testing to achieve FAA certification for the first of the many DC-8 variants in August 1959. Much needed to be done: the original air brakes on the lower rear fuselage were found ineffective and were deleted as engine thrust reversers had become available; unique leading-edge slots were added to improve low-speed lift; the prototype was 25 kn (46 km/h) short of its promised cruising speed and a new, slightly larger wingtip had to be developed to reduce drag. In addition, a recontoured wing leading edge was later developed to extend the chord 4% and reduce drag at high Mach numbers.[4]

On August 21, 1961, a Douglas DC-8 broke the sound barrier at Mach 1.012 (660 mph/1,062 km/h) while in a controlled dive through 41,000 feet (12,497 m) and maintained that speed for 16 seconds. The flight was to collect data on a new leading-edge design for the wing, and while doing so, the DC-8 became the first civilian jet – and the first jet airliner – to make a supersonic flight.[5] The aircraft was DC-8-43 registered CF-CPG later delivered to Canadian Pacific Air Lines. The aircraft, crewed by Captain William Magruder, First Officer Paul Patten, Flight Engineer Joseph Tomich and Flight Test Engineer Richard Edwards, took off from Edwards Air Force Base in California, and was accompanied to altitude by an F-104 Starfighter supersonic chase aircraft flown by Chuck Yeager.[6]

Entry into service

On September 18, 1959, the DC-8 entered service with Delta Air Lines and United Airlines.[7] According to the Delta Air Lines website, the air carrier was the first to operate the DC-8 in scheduled passenger service.[8] By March 1960, Douglas had reached their planned production rate of eight DC-8s a month. Despite a large number of DC-8 early models available, all used the same basic airframe, differing only in engines, weights and details; in contrast, Boeing's rival B707 range offered several fuselage lengths and two wingspans: the original 144-foot (44 m) 707-120, a 135-foot (41 m) version that sacrificed space to gain longer range, and the stretched 707-320, which at 153 feet (47 m) overall had 10 feet (3.0 m) more cabin space than the DC-8. Douglas' refusal to offer different fuselage sizes made it less adaptable and forced Delta and United to look elsewhere for short/medium range types. Delta ordered Convair 880s but United went for the newly developed lightweight 707-020 but prevailed on Boeing to rename the new variant the "Boeing 720" in case people thought they were dissatisfied with the DC-8. Pan Am never reordered the DC-8 and Douglas gradually lost market share to Boeing. In 1962 DC-8 sales dropped to just 26, followed by 21 in 1963 and 14 in 1964; many were for the Jet Trader rather than the more prestigious passenger versions. In 1967, Douglas merged with McDonnell Aircraft Corporation to become McDonnell Douglas.[9]

Further developments

In April 1965, Douglas announced belated fuselage stretches for the DC-8 with three new models known as the Super Sixties. The DC-8 program had been in danger of closing with fewer than 300 aircraft sold, but the Super Sixties brought fresh life to it. By the time production ceased in 1972, 262 of the stretched DC-8s had been made. With the ability to seat 269 passengers, the DC-8 Series 61 and 63 had the largest passenger-carrying capacity available. That remained so until the Boeing 747 arrived in 1970. The DC-8-62 featured a shorter fuselage when compared with the Series 61 and 63 but was capable of nonstop long range operations.

All the earlier jetliners were noisy by modern standards. Increasing traffic densities and changing public attitudes led to complaints about aircraft noise and moves to introduce restrictions. As early as 1966 the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey expressed concern about the noise to be expected from the then still-unbuilt DC-8-61, and operators had to agree to operate it from New York at lower weights to reduce noise. By the early 1970s, legislation for aircraft noise standards was being introduced in many countries, and the 60 Series DC-8s were particularly at risk of being banned from major airports.

In the early 1970s several airlines approached McDonnell Douglas for noise reduction modifications to the DC-8 but nothing was done. Third parties had developed aftermarket hushkits but there was no real move to keep the DC-8 in service. Finally, in 1975, General Electric began discussions with major airlines with a view to fitting the new and vastly quieter Franco-American CFM56 engine to both DC-8s and 707s. MDC remained reluctant but eventually came on board in the late 1970s and helped develop the Series 70.[10]

The Super Seventies were a great success: roughly 70% quieter than the 60-Series and, at the time of their introduction, the world's quietest four-engined airliner. As well as being quieter and more powerful, the CFM56 was up to 23% more fuel efficient than the JT3D, which reduced operating costs and extended the range.[10]

By 2002, of the 1,032 Boeing 707s and 720s manufactured for commercial use, just 80 remained in service – though many of those 707s were converted for USAF use, either in service or for spare parts. Of the 556 DC-8s made, around 200 were still in commercial service in 2002, including about 25 50-Series, 82 of the stretched 60-Series, and 96 out of the 110 re-engined 70-Series. Most of the surviving DC-8s are now used as freighters. In May 2009, 97 DC-8s were in service following UPS's decision to retire their remaining fleet of 44.[11] In January 2013, an estimated 36 DC-8s were in use worldwide.[12] As a result of aging, increasing operating costs and strict noise and emissions regulations, the number of active DC-8s continues to decline.

Variants

Series 10

For domestic use, powered by 13,500 lb (60.5 kN) Pratt & Whitney JT3C-6 turbojets with water injection. The initial DC-8-11 model had the original, high-drag wingtips and all were converted to DC-8-12 standard. The DC-8-12 had the new wingtips and leading-edge slots, 80 inches long between the engines on each wing and 34 inches long inboard of the inner engines. These unique devices were covered by doors on the upper and lower wing surfaces that opened for low speed flight and closed for cruise. The maximum weight increased from 265,000 to 273,000 pounds (120,200 to 123,800 kg). 28 DC-8-10s were built. This model was originally named "DC-8A" until the series 30 was introduced.[13] 29 built, 22 for United and 6 for Delta, plus the prototype. By the mid sixties United had converted 15 of its 20 surviving aircraft to DC-8-20 standard and the other 5 to -50s. Delta converted its 6 to DC-8-50s.

Series 20

Higher-powered 15,800 lb (70.8 kN) thrust Pratt & Whitney JT4A-3 turbojets (without water injection) allowed a weight increase to 276,000 pounds (125,190 kg). 34 DC-8-20s were built plus 15 converted DC-8-10s. This model was originally named "DC-8B" but was renamed when the series 30 was introduced.[13]

Series 30

For intercontinental routes, the three Series 30 variants combined JT4A engines with a one-third increase in fuel capacity and strengthened fuselage and landing gear. The DC-8-31 was certified in March 1960 with 16,800 lb (75.2 kN) JT4A-9 engines for 300,000-pound (136,080 kg) maximum takeoff weight. The DC-8-32 was similar but allowed 310,000-pound (140,600 kg) weight. The DC-8-33 of November 1960 substituted 17,500 lb (78.4 kN) JT4A-11 turbojets, a modification to the flap linkage to allow a 1.5° setting for more efficient cruise, stronger landing gear, and 315,000-pound (142,880 kg) maximum weight. Many -31 and -32 DC-8s were upgraded to this standard. A total of 57 DC-8-30s were produced.

Series 40

The DC-8-40 was essentially the -30 but with 17,500 lb (78.4 kN) Rolls-Royce Conway 509 turbofan engines for better efficiency, less noise and less smoke. The Conway was an improvement over the turbojets that preceded it, but the Series 40 sold poorly because of the traditional reluctance of U.S. airlines to buy a foreign product and because the still more advanced Pratt & Whitney JT3D turbofan was due in early 1961. The DC-8-41 and DC-8-42 had weights of 300,000 and 310,000 pounds (140,000 and 140,000 kg) respectively, The 315,000-pound (142,880 kg) DC-8-43 had the 1.5° flap setting of the -33 and introduced a 4% leading edge wing extension to reduce drag and increase fuel capacity slightly – the new wing improved range by 8%, lifting capacity by 6,600 lb (3 metric tons), and cruising speed by better than 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). It was used on all later DC-8s. The first DC-8-40 was delivered in 1960; 32 were built.

Series 50

The definitive short-fuselage DC-8 came with the same engine that powered the vast majority of 707s, the JT3D. Fourteen earlier DC-8s were converted to this standard. All but the -55 were certified in 1961. The DC-8-51, DC-8-52 and DC-8-53 all had 17,000 lb (76.1 kN) JT3D-1 or 18,000 lb (80.6 kN) JT3D-3B engines, varying mainly in their weights: 276,000 pounds (125,200 kg), 300,000 pounds (136,100 kg) and 315,000 pounds (142,900 kg) respectively. The DC-8-55 arrived in June 1964, retaining the JT3D-3B engines but with strengthened structure from the freighter versions and 325,000-pound (147,420 kg) maximum weight. 88 DC-8-50s were built plus the 14 converted from Series 10/30.

- DC-8 Jet Trader: Douglas approved development of freighter versions of the DC-8 in May 1961, based on the Series 50. An original plan to fit a fixed bulkhead separating the forward ⅔ of the cabin for freight, leaving the rear cabin for 54 passenger seats was soon replaced by a more practical one to use a movable bulkhead and allow anywhere between 25 and 114 seats with the remainder set aside for cargo. A large cargo door was fitted into the forward fuselage, the cabin floor was reinforced and the rear pressure bulkhead was moved by nearly 7 feet (2.1 m) to make more space. Airlines could order a windowless cabin but only United did, ordering 15 in 1964. The DC-8F-54 had a maximum takeoff weight of 315,000 pounds (142,880 kg) and the DC-8F-55 325,000 pounds (147,420 kg). Both used 18,000 lb (80.6 kN) JT3D-3B powerplants. 54 aircraft built.

- EC-24A: A single former United Airlines DC-8-54 (F) was used by the United States Navy as an electronic warfare training platform. It was retired in October 1998 and is now in storage with the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group.[14]

Super 60 Series

- DC-8 Series 61: The "Super DC-8" Series 61 was designed for high capacity and medium range. It had the same wings, engines and pylons as the -55, and sacrificed range to gain capacity. Having decided to stretch the DC-8, Douglas inserted a 240-inch (6.1 m) plug in the forward fuselage and a 200-inch (5.1 m) plug aft, taking overall length to 187 feet 4 inches (57.10 m). The added length required strengthening of the structure, but the basic DC-8 design already had sufficient ground clearance to permit the one-third increase in cabin size without requiring longer landing gear.[15] The variant first flew on March 14, 1966, and was certified on September 2, 1966, at a maximum weight of 325,000 pounds (147,420 kg).[16] Deliveries began in January 1967 and it entered service with United Airlines in February 1967.[17][18] It typically carried 180–220 passengers in mixed-class configuration, or 259 in high-density configuration.[19] A cargo door equipped DC-8-61CF was also available. 78 -61s and 10 -61CFs were built.[15]

- DC-8 Series 62: The long-range Series 62 followed in April 1967. It had a more modest stretch, two 40-inch (1.0 m) plugs fore and aft of the wing taking overall length to 157 feet 5 inches (47.98 m), and a number of modifications to provide greater range. 3 feet (0.91 m) wingtip extensions reduced drag and added fuel capacity, and Douglas redesigned the engine pods, extending the pylons and substituting new shorter and neater nacelles, all in the cause of drag reduction. The 18,000 lb JT3D-3B was retained but the engine pylons were redesigned to eliminate their protrusion above the wing and make them sweep forward more sharply, so that the engines were some 40 inches (1.0 m) further forward. The engine pods were also modified with a reduction in diameter and the elimination of the -50 and -61 bypass duct. The changes all improved the aircraft's aerodynamic efficiency. The DC-8 Series 62 is slightly heavier than the -53 or -61 at 335,000 pounds (151,953 kg), and able to seat up to 189 passengers, the -62 had a range with full payload of about 5,200 nautical miles (9,600 km; 6,000 mi), or about the same as the -53 but with 40 extra passengers. Many late production -62s had 350,000 pounds (158,760 kg) maximum takeoff weight and were known as the -62H.[20] Also available as the cargo door equipped convertible -62CF or all cargo -62AF. Production included 51 DC-8-62s, 10 -62CFs, and 6 -62AFs.[21]

- DC-8 Series 63: The "Super DC-8" Series 63 was the final new-build variant and entered service in June 1968. It had the long fuselage of the -61, the aerodynamic refinements and increased fuel capacity of the -62 and 19,000 lb (85.1 kN) JT3D-7 engines.[22] This allowed a maximum takeoff weight of 350,000 pounds (158,760 kg).[23] Like the -62, the Series 63 was also available as a cargo door equipped -63CF or all cargo -63AF. The freighters had a further increase in Maximum Take Off Weight to 355,000 pounds (161,030 kg). Eastern Airlines bought six -63PFs with the strengthened floor of the freighters but no cargo door. Production included 41 DC-8-63s, 53 -63CF, 7 -63AF, and 6 -63PFs.[24] The Flying Tiger Line was a major early customer for the DC-8-63F.

Super 70 Series

The DC-8-71, DC-8-72 and DC-8-73 were straightforward conversions of the -61, -62 and -63 primarily involving replacement of the JT3D engines with more fuel-efficient 22,000 lb (98.5 kN) CFM56-2 high-bypass turbofans with new nacelles and pylons built by Grumman Aerospace and fairing of the air intakes below the nose. The DC-8-71 achieved the same end but required more modification because the -61 did not have the improved wings and relocated engines of the -62 and -63. Maximum takeoff weights remained the same, but there was a slight reduction in payload because of the heavier engines. All three models were certified in 1982 and a total of 110 60-Series DC-8s were converted by the time the program ended in 1988. DC-8-70 conversions were overseen by Cammacorp with CFMI, McDonnell Douglas, and Grumman Aerospace as partners. Cammacorp was disbanded after the last aircraft was converted.[10]

Operators

As of July 2018, one DC-8 remains in commercial service with Trans Air Cargo Service (1).[25] In addition, several DC-8s are in use as private aircraft along with one in use by NASA for air quality testing as of October 2017. As of 2017, Skybus Cargo Charters based in Las Vegas, Nevada lists three DC-8 Super 70 series aircraft in its fleet including a DC-8-72 in VIP passenger configuration, a DC-8-72CF Combi aircraft capable of transporting both passengers and cargo on the main deck and a DC-8-73F cargo aircraft.[26]

Accidents and incidents

As of October 2015, the DC-8 had been involved in 146 incidents,[27] including 83 hull-loss accidents,[28] with 2,256 fatalities.[29] The DC-8 has also been involved in 46 hijackings with 2 fatalities.[30]

Aircraft on display

The following museums have DC-8s on display or in storage:

- The forward section of a DC-8-32 operated by Japan Airlines, Fuji, is on display at Haneda Airport, Tokyo. The first jet airliner used by the airline, she was retired from service in 1974 for use as a cockpit trainer.[31]

- 45280 – DC-8-21 on display at the Chinese Aviation Museum in Datangshan, China. It is an ex-United Airlines aircraft formerly used as flying eye hospital by ORBIS International.[32]

- 45570 – DC-8-33 on display at the Musée de l'Air at the Paris–Le Bourget Airport in Paris, France. It is an ex-French Air Force electronic warfare aircraft and has been on display since its retirement in 2001.[33][34]

- 45850 – DC-8-52 on display at the California Science Center in Exposition Park, Los Angeles, California. It is an ex-United Airlines aircraft and is on display outside near Downtown LA.[35][36][37]

- 45922 – DC-8-62CF on display at the Naval Air Museum Barbers Point at Kalaeloa Airport in Kapolei, Hawaii. Operated by Air Transport International for 15 years until its retirement to the museum in 2013, it was one of the very last DC-8s flying.[38]

- 46160 – DC-8-61 on display at the Shanghai Aerospace Enthusiasts Centre in Shanghai, China. It is an ex-Japan Airlines aircraft on display outside near downtown.[39][40]

Specifications

| Variant | -10/20/30 | -40/43/50/55 | -61/71 | -63/73 | -62/72 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passengers | 177 | -40/43: 177, -50/55: 189 | 259 | 189 | |

| Max. cargo | 1,390 cu ft (39 m3) | 2,500 cu ft (71 m3) | 1,615 cu ft (45.7 m3) | ||

| Wingspan | 142.4 ft (43.4 m) | 148.4 ft (45.2 m) | |||

| Length | 150.7 ft (45.9 m) | 187.4 ft (57.1 m) | 157.5 ft (48.0 m) | ||

| Fuselage | outside width: 147 in (373.4 cm), inside width: 138.25 in (351.2 cm) | ||||

| MTOW | -10: 273,000 lb (123.8 t) -20: 276,000 lb (125.2 t) 30: 315,000 lb (142.9 t) |

315,000 lb (142.9 t) -55: 325,000 lb (147.4 t) |

325,000 lb (147.4 t) -F: 328,000 lb (148.8 t) |

355,000 lb (161.0 t) | 350,000 lb (158.8 t) -72F : 335,000 lb (152.0 t) |

| Max PL | -10: 46,103 lb (20.9 t) -20: 43,624 lb (19.8 t) -30: 51,870 lb (23.5 t) |

52,000 lb (23.6 t) -43: 41,691 lb (18.9 t) |

-61: 71,899 lb (32.6 t) -71: 60,300 lb (27.4 t) |

-63: 71,262 lb (32.3 t) -73: 64,800 lb (29.4 t) |

-62: 51,745 lb (23.5 t) -72: 41,800 lb (19.0 t) |

| OEW | -10: 119,797 lb (54.3 t) -20: 123,876 lb (56.2 t) -30: 126,330 lb (57.3 t) |

-40/50: 124,800 lb (56.6 t) -43: 136,509 lb (61.9 t) -55: 138,266 lb (62.7 t) |

-61: 152,101 lb (69.0 t) -71: 163,700 lb (74.3 t) |

-63: 158,738 lb (72.0 t) -73: 166,200 lb (75.4 t) |

-62: 143,255 lb (65.0 t) -72: 153,200 lb (69.5 t) |

| Max fuel | 23,393 US gal (88.6 m3), -10/20: 17,550 US gal (66.4 m3) | 24,275 US gal (91.9 m3) | |||

| Turbojets | -10: P&W JT3C -20/30: P&W JT4A |

-40/43: RCo.12 -50/55: P&W JT3D-3 |

super 60: P&W JT3D-3B super 70: CFM56-2 | ||

| Turbofans | |||||

| Cruise speed | Mach 0.82 (483 kn; 895 km/h) | ||||

| Range[lower-alpha 1] | -10: 3,760 nmi (6,960 km) -20: 4,050 nmi (7,500 km) -30: 4,005 nmi (7,417 km) |

-40: 5,310 nmi (9,830 km) -43: 4,200 nmi (7,800 km) -50: 5,855 nmi (10,843 km) -55: 4,700 nmi (8,700 km) |

-61: 3,200 nmi (5,900 km) -71: 3,500 nmi (6,500 km) |

-63: 4,000 nmi (7,400 km) -73: 4,500 nmi (8,300 km) |

-62: 5,200 nmi (9,600 km) -72: 5,300 nmi (9,800 km) |

| Freighter versions | -50/-55 | -61/71 | 63/73 | -62/72 | |

| Volume | -50: 9,310 cu ft (264 m3) -55: 9,020 cu ft (255 m3) |

12,171 cu ft (344.6 m3) | 12,830 cu ft (363 m3) | 9,737 cu ft (275.7 m3) | |

| Payload | -50: 88,022 lb (39.9 t) -55: 92,770 lb (42.1 t) |

-61: 88,494 lb (40.1 t) -71: 81,300 lb (36.9 t) |

-63: 119,670 lb (54.3 t) -73: 111,800 lb (50.7 t) |

-62: 91,440 lb (41.5 t) -72: 90,800 lb (41.2 t) | |

| OEW | -50: 130,207 lb (59.1 t) -55: 131,230 lb (59.5 t) |

-61: 145,506 lb (66.0 t) -71: 152,700 lb (69.3 t) |

-63: 141,330 lb (64.1 t) -73: 149,200 lb (67.7 t) |

-62: 138,560 lb (62.8 t) -72: 140,200 lb (63.6 t) | |

| Max PL Range |

-55: 3,000 nmi (5,600 km) | -61/63: 2,300 nmi (4,300 km) -71/73: 2,900 nmi (5,400 km) |

-62: 3,200 nmi (5,900 km) -72: 3,900 nmi (7,200 km) | ||

Deliveries

| 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 91 | 42 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 31 | 32 | 41 | 102 | 85 | 33 | 13 | 4 | 556 |

| -10 | -20 | -30 | -40 | -50 | -61 | -62 | -63 | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | 34 | 57 | 32 | 142 | 88 | 67 | 107 | 556 |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

Notes

- ↑ -10/20/30/40/50: max PL, -43/55/super 60/super 70: max pax

References

- ↑ Flight 18 November 1960, p. 803.

- ↑ Garvey, William. "Battled field". Aviation Week and Space Technology, Vol. 176, No. 6, February 24, 2014, p.18. (Registration required).

- ↑ Francillon 1979, p. 582.

- ↑ Shevell, R.S. (October 1985). "Aerodynamics Bugs: Can CFD Spray Them Away?". AIAA. doi:10.2514/6.1985-4067.

- ↑ "Douglas Passenger Jet Breaks Sound Barrier". DC8.org. August 21, 1961.

- ↑ Wasserzieher, Bill. "I Was There: When the DC-8 Went Supersonic, The day a Douglas DC-8 busted Mach 1". Air & Space/Smithsonian, August 2011, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Whittle 1972, p. 5.

- ↑ "Douglas DC-8 1959-1989". Delta Flight Museum.

- ↑ "McDonnell Douglas Corporation". britannica.com.

- 1 2 3 Kingsley-Jones and Doyle Flight International 4–10 December 1996, p. 57.

- ↑ "Final UPS DC-8 flight lands at Louisville International Airport". Business First of Louisville. May 11, 2009. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- ↑ Bostick, Brian (January 10, 2013). "DC-8 Operations in US Winding Down". Aviation Week. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- 1 2 Norris, Guy; Wagner, Mark (1999). Douglas Jetliners. MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0676-1.

- ↑ "EC-24A". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- 1 2 Francillon 1979, pp. 588–589.

- ↑ Taylor 1966, pp. 231–233.

- ↑ "Air Transport". Flight International. Vol. 91 no. 3022. 9 February 1967. p. 192.

- ↑ Harrison, Neil (23 November 1967). "Commercial Aircraft Survey: DC-8-61". Flight International. Vol. 92 no. 3063. p. 852.

- ↑ Francillon 1979, p. 598.

- ↑ Whittle 1972, p. 11.

- ↑ Francillon 1979, pp. 590–591.

- ↑ Francillon 1979, pp. 591–593, 598.

- ↑ Francillon 1979, p. 591.

- ↑ Francillon 1979, pp. 591–593.

- ↑ "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 2018-08-26.

- ↑ "Charter Airlines - Skybus Air Cargo - Company". Charter Airlines - Skybus Air Cargo.

- ↑ "Douglas DC-8 incidents". Aviation Safety Network. October 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Douglas DC-8 summary". Aviation Safety Network. October 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Douglas DC-8 Accident Statistics". Aviation Safety Network. October 11, 2015.

- ↑ "DC-8 Statistics". Aviation Safety Network. October 11, 2015.

- ↑ "JA8001 Japan Airlines Douglas DC-8-32 - cn 45418 / 78". Planespotters.net. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Airframe Dossier - DouglasDC-8 / C-24, c/n 45280, c/r N220RB". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Douglas DC-8 SARIGuE F-RAFE". Musée de l’Air et de l’Espace (in French). Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Airframe Dossier - Douglas DC-8-33, s/n 45570 ALA, c/n 45570, c/r F-BIUZ". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ Harrison, Scott. "DC-8 for California Museum of Science and Industry". LA Times, September 14, 2012.

- ↑ "SKETCH Foundation Air and Space Exhibits". California Science Center. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Airframe Dossier - Douglas DC-8-52, c/n 45850, c/r N8066U". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Douglas DC-8-62CF Construction No. 45922". Naval Air Museum Barbers Point. Naval Air Museum Barbers Point. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "About Centre". Shanghai Aerospace Enthusiasts Centre (in Chinese). Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Airframe Dossier - Douglas DC-8 / C-24, c/n 46160, c/r JA8048". Aerial Visuals. AerialVisuals.ca. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "Commercial Aircraft of the World" (PDF). Flight. 23 November 1961.

- ↑ "Airplane Characteristics for Airport Planning" (PDF). Boeing. 1989.

Bibliography

- "Commercial Aircraft of the World. Flight, Volume 78, No. 2697, 18 November 1960. pp. 781–827.

- "Commercial Aircraft of the World". Flight, Volume 80, No. 2750, 23 November 1961. pp. 799–836.

- Francillon, Rene J., McDonnell Douglas Aircraft since 1920, Putnam & Company Ltd, 1979, ISBN 0-370-00050-1.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max and Doyle, Andrew. "Airliners of the World". Flight International, Volume 150, No. 4552, 4–10 December 1996. pp. 39–70. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Norris, Guy, and Wagner, Mark. Douglas Jetliners. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0676-1.

- Thisdell, Dan and Fafard, Antoine. "World Airliner Census". Flight International, Volume 190, No. 5550, 9–15 August 2016. pp. 20–43. ISSN 0015-3710

- Whittle, John A., Nash, H.J., and Sievers, Harry. The McDonnell DC-8. Tonbridge, Kent, UK: Air-Britain, 1972. ISBN 0-85130-024-3.

Further reading

- Cearley, George Walker. The Douglas DC-8: A Pictorial History. Dallas: G.W. Cearley, Jr., 1992.

- Douglas Aircraft Co. The DC-8 Story. Long Beach, CA: Douglas Aircraft Company, 1972.

- Douglas Aircraft Co. Douglas DC-8 Maintenance Manual. Long Beach, CA: Douglas Aircraft Company, 1959. OCLC 10621428.

- Hubler, Richard G. Big Eight: A Biography of an Airplane. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1960.

- Lundkvist, Bo-Goran. Douglas DC-8. Coral Springs, FL: Lundkvist Aviation Research, 1983. OCLC 62220710.

- McDonnell-Douglas. The DC-8 Super-Sixty. Long Beach, CA: McDonnell Douglas Corp. Sales Engineering Div., 1968.

- McDonnell-Douglas. The DC-8 Handbook. Long Beach, CA: McDonnell Douglas Corp. Sales Engineering Div., 1982.

- Proctor, Jon, Machat, Mike, Kodeta, Craig. From Props to Jets: Commercial Aviatin's Transition to the Jet Age 1952–1962. North Branch, MN: Specialty Press. ISBN 1-58007-146-5.

- Vicenzi, Ugo. Early American Jetliners: Boeing 707, Douglas DC-8 and Convair CV880. Osceola, WI: MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0788-1.

- Waddington, Terry. Douglas DC-8. Miami, FL: World Transport Press, 1996. ISBN 0-9626730-5-6.

- Wilson, Stewart. Airliners of the World. Fyshwick, Australia, ACT: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd., 1999. ISBN 1-875671-44-7.

- Wilson, Stewart. Boeing 707, Douglas DC-8, and Vickers VC-10. Fyshwick, Australia, ACT: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd., 1998. ISBN 1-875671-36-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Douglas DC-8. |

- DC-8 page on Airliners.net

- DC-8 Airborne Laboratory fact sheet on NASA/Dryden FRC's site

- "freighter version" (PDF). Boeing. 2007.

Douglas and McDonnell Douglas aircraft production timeline, 1950-2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1950s | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| Douglas DC-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| DC-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Douglas DC-8 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| McDonnell Douglas DC-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| McDonnell Douglas MD-80 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MDD MD-90 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| MD-95 / B717 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| McDonnell Douglas DC-10 | MD-11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| = Piston-engined | = Narrow-body jet | = Wide-body jet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||