Dermatitis herpetiformis

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Duhring's disease[1][2] |

| |

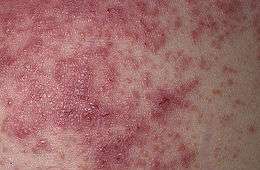

| Characteristic rash of dermatitis herpetiformis | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Dermatitis herpetiformis (DH) is a chronic blistering skin condition,[3] characterised by blisters filled with a watery fluid.[4] Despite its name, DH is neither related to nor caused by herpes virus: the name means that it is a skin inflammation having an appearance similar to herpes.

Dermatitis herpetiformis was first described by Louis Adolphus Duhring in 1884.[5] A connection between DH and celiac disease was recognised in 1967,[5][6] although the exact causal mechanism is not known. DH is a specific manifestation of coeliac disease.[7]

The age of onset is usually about 15–40, but DH also may affect children and the elderly. Men and women are affected equally. Estimates of DH prevalence vary from 1 in 400 to 1 in 10,000. It is most common in patients of northern European/northern Indian ancestry, and is associated with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) haplotype HLA-DQ2 along with coeliac disease and gluten sensitivity.[8][9][10][11]

Signs and symptoms

Dermatitis herpetiformis is characterized by intensely itchy, chronic papulovesicular eruptions, usually distributed symmetrically on extensor surfaces (buttocks, back of neck, scalp, elbows, knees, back, hairline, groin, or face).[1]:616[9][12] The blisters vary in size from very small up to 1 cm across.

The condition is extremely itchy, and the desire to scratch may be overwhelming.[13] This sometimes causes the sufferer to scratch the blisters off before they are examined by a physician.[9] Intense itching or burning sensations are sometimes felt before the blisters appear in a particular area.[4][14]

Untreated, the severity of DH may vary significantly over time, in response to the amount of gluten ingested.[14]

Dermatitis herpetiformis symptoms typically first appear in the early years of adulthood between 20 and 30 years of age.[15]

Although the first signs and symptoms of dermatitis herpetiformis are intense itching and burning, the first visible signs are the small papules or vesicles that usually look like red bumps or blisters. The rash rarely occurs on other mucous membranes, excepting the mouth or lips. The symptoms range in severity from mild to serious, but they are likely to disappear if gluten ingestion is avoided and appropriate treatment is administered.

Dermatitis herpetiformis symptoms are chronic, and they tend to come and go, mostly in short periods of time. Sometimes, these symptoms may be accompanied by symptoms of coeliac disease, commonly including abdominal pain, bloating or loose stool, and fatigue.

The rash caused by dermatitis herpetiformis forms and disappears in three stages. In the first stage, the patient may notice a slight discoloration of the skin at the site where the lesions appear. In the next stage, the skin lesions transform into obvious vesicles and papules that are likely to occur in groups. Healing of the lesions is the last stage of the development of the symptoms, usually characterized by a change in the skin color. This may result in areas of the skin turning darker or lighter than the color of the skin on the rest of the body. Because of the intense itching, patients usually scratch, which may lead to the formation of crusts.

Pathophysiology

In terms of pathology, the first signs of the condition may be observed within the dermis. The changes that may take place at this level may include edema, vascular dilatation, and cellular infiltration. It is common for lymphocytes and eosinophils to be seen. The bullae found in the skin affected by dermatitis herpetiformis are subepidermal and have rounded lateral borders.

When looked at under the microscope, the skin affected by dermatitis herpetiformis presents a collection of neutrophils. They have an increased prevalence in the areas where the dermis is closest to the epidermis.

Direct IMF studies of uninvolved skin show IgA in the dermal papillae and patchy granular IgA along the basement membrane. The jejunal mucosa may show partial villous atrophy, but the changes tend to be milder than in coeliac disease.[16]

Immunological studies revealed findings that are similar to those of coeliac disease in terms of autoantigens. The main autoantigen of dermatitis herpetiformis is epidermal transglutaminase (eTG), a cytosolic enzyme involved in cell envelope formation during keratinocyte differentiation.[8]

Various research studies have pointed out different potential factors that may play a larger or smaller role in the development of dermatitis herpetiformis. The fact that eTG has been found in precipitates of skin-bound IgA from skin affected by this condition has been used to conclude that dermatitis herpetiformis may be caused by a deposition of both IgA and eTG within the dermis. It is estimated that these deposits may resorb after ten years of following a gluten-free diet. Moreover, it is suggested that this condition is closely linked to genetics. This theory is based on the arguments that individuals with a family history of gluten sensitivity who still consume foods containing gluten are more likely to develop the condition as a result of the formation of antibodies to gluten. These antibodies cross-react with eTG, and IgA/eTG complexes deposit within the papillary dermis to cause the lesions of dermatitis herpetiformis. These IgA deposits may disappear after long-term (up to ten years) avoidance of dietary gluten.[8]

Gliadin proteins in gluten are absorbed by the gut and enter the lamina propria where they need to be deamidated by tissue transglutanimase (tTG). tTG modifies gliadin into a more immunogenic peptide. Classical dendritic cells (cDCs) endocytose the immunogenic peptide and if their pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are stimulated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or danger-associated molecular pattern (DAMPs), the danger signal will influence them to secrete IL-8 (CXCL8) in the lamina propria, recruiting neutrophils. Neutrophil recruitment results in a very rapid onset of inflammation. Therefore, co-infection with microbes that carry PAMPs may be necessary for the initial onset of symptoms in gluten sensitivity, but would not be necessary for successive encounters with gluten due to the production of memory B and memory T cells (discussed below).

Dermatitis herpetiformis may be characterised based on inflammation in the skin and gut. Inflammation in the gut is similar to, and linked to, celiac disease. tTG is treated as an autoantigen, especially in people with certain HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 alleles and other gene variants that cause atopy. tTG is up-regulated after gluten absorption. cDCs endocytose tTG-modified gliadin complexes or modified gliadin alone but they only present gliadin to CD4+ T cells on pMHC-II complexes. These T cells become activated and polarised into type I helper T (Th1) cells. Th1 cells reactive towards gliadin have been discovered, but none against tTG. A naive B cell sequesters tTG-modified gliadin complexes from the surface of cDCs in the lymph nodes (LNs) before they become endocytosed by the cDCs. The B cell receptor (membrane bound antibody; BCR) is specific to the tTG portion of the complex. The B cell endocytoses the complex and presents the modified gliadin to the activated Th1 cell's T cell receptor (TCR) via pMHC-II in a process known as epitope spreading. Thus, the B cell presents the foreign peptide (modified gliadin) but produces antibodies specific for the self-antigen (tTG). Once the B cell becomes activated, it differentiates into plasma cells that secrete autoantibodies against tTG, which may be cross-reactive with epidermal transglutanimase (eTG). Class A antibodies (IgA) deposit in the gut. Some may bind to the CD89 (FcαRI) receptor on macrophages (M1) via their Fc region (constant region). This will trigger endocytosis of the tTG-IgA complex, resulting in the activation of macrophages. Macrophages secrete more IL-8, propagating the neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response.

The purportedly cross-reactive autoantibodies may migrate to the skin in dermatitis herpetiformis. IgA deposits may form if the antibodies cross-react with epidermal transglutanimase (eTG). Some patients have eTG-specific antibodies instead of tTG-specific cross-reactive antibodies and the relationship between dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac disease in these patients is not fully understood. Macrophages may be stimulated to secrete IL-8 by the same process as is seen in the gut, causing neutrophils to accumulate at sites of high eTG concentrations in the dermal papillae of the skin. Neutrophils produce pus in the dermal papillae, generating characteristic blisters. IL-31 accumulation at the blisters may intensify itching sensations. Memory B and T cells may become activated in the absence of PAMPs and DAMPs during successive encounters with tTG-modified gliadin complexes or modified gliadin alone, respectively. Symptoms of dermatitis herpetiformis are often resolved if patients avoid a gluten-rich diet.[17][18][19]

Diagnosis

Dermatitis herpetiformis often is misdiagnosed, being confused with drug eruptions, contact dermatitis, dishydrotic eczema (dyshidrosis), and even scabies.[20]

The diagnosis may be confirmed by a simple blood test for IgA antibodies against tissue transglutaminase (which cross-react with epidermal transglutaminase),[21] and by a skin biopsy in which the pattern of IgA deposits in the dermal papillae, revealed by direct immunofluorescence, distinguishes it from linear IgA bullous dermatosis[9] and other forms of dermatitis. These tests should be performed before the patient starts on a gluten-free diet,[14] otherwise they might produce false negatives. As with ordinary celiac disease, IgA against transglutaminase disappears (often within months) when patients eliminate gluten from their diet. Thus, for both groups of patients, it may be necessary to restart gluten for several weeks before testing may be done reliably. In 2010, Cutis reported an eruption labelled gluten-sensitive dermatitis which is clinically indistinguishable from dermatitis herpetiformis, but lacks the IgA connection,[22] similar to gastrointestinal symptoms mimicking coeliac disease but without the diagnostic immunological markers.[23]

Treatment

A strict gluten-free diet must be followed,[21] and usually, this treatment will be a lifelong requirement. Avoidance of gluten will reduce any associated intestinal damage [13][21] and the risk of other complications.

Dapsone is an effective initial treatment in most people. Itching is typically reduced within 2–3 days,[13][24] however, dapsone treatment has no effect on any intestinal damage that might be present.[11][25] After some time on a gluten-free diet, the dosage of dapsone usually may be reduced or even stopped,[13] although this may take many years. Dapsone is an antibacterial, and its role in the treatment of DH, which is not caused by bacteria, is poorly understood. It may cause adverse effects, so regular blood monitoring is required.[4]

Dapsone is the drug of choice. For individuals with DH unable to tolerate dapsone for any reason, alternative treatment options may include the following:

Prognosis

Dermatitis herpetiformis generally responds well to medication and changes in diet. It is an autoimmune disease, however, and patients with DH are more likely than others to have thyroid problems[9][21] and intestinal lymphoma.[9][10][12]

Dermatitis herpetiformis does not usually cause complications on its own, without being associated with another condition. Complications from this condition, however, arise from the autoimmune character of the disease, as an overreacting immune system is a sign that something does not work well and might cause problems to other parts of the body that do not necessarily involve the digestive system.[26]

Gluten intolerance and the body's reaction to it make the disease more worrying in what concerns the possible complications. This means that complications that may arise from dermatitis herpetiformis are the same as those resulting from coeliac disease, which include osteoporosis, certain kinds of gut cancer, and an increased risk of other autoimmune diseases such as thyroid disease.

The risks of developing complications from dermatitis herpetiformis decrease significantly if the affected individuals follow a gluten-free diet. The disease has been associated with autoimmune thyroid disease, insulin-dependent diabetes, lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, sarcoidosis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata.[27]

Notable cases

It has been suggested that French revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat had DH,[28] leading him to spend much of his time in, and even work from, a bathtub filled with a herbal mixture that he used as a palliative for the sores.

See also

References

- 1 2 Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

- ↑ Singal A, Bhattacharya SN, Baruah MC (2002). "Dermatitis herpetiformis and rheumatoid arthritis". Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 68 (4): 229–30. PMID 17656946.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". American Osteopathic College of Dermatology.

- 1 2 "What Is Dermatitis Herpetiformis?".

- ↑ Marietta EV, Camilleri MJ, Castro LA, Krause PK, Pittelkow MR, Murray JA (February 2008). "Transglutaminase autoantibodies in dermatitis herpetiformis and celiac sprue". J. Invest. Dermatol. 128 (2): 332–5. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5701041. PMID 17762854.

- ↑ "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". Retrieved 2015-04-20.

- 1 2 3 Miller JL, Collins K, Sams HH, Boyd A (2007-05-18). "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". emedicine from WebMD.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Van L, Browning JC, Krishnan RS, Kenner-Bell BM, Hsu S (2008). "Dermatitis herpetiformis: Potential for confusion with linear IgA bullous dermatosis on direct immunofluorescence". Dermatology Online Journal. 14 (1): 21. PMID 18319038.

- 1 2 "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". Patient UK.

- 1 2 "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse.

- 1 2 Turchin I, Barankin B (2005). "Dermatitis herpetiformis and gluten-free diet". Dermatology Online Journal. 11 (1): 6. PMID 15748547.

- 1 2 3 4 "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". The HealthScout Network.

- 1 2 3 "Detecting Celiac Disease in Your Patients". American Family Physician. American Academy of Family Physicians.

- ↑ "Dermatitis Herpetiformis". Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ "Perioral Dermatitis". Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ Murphy, Kenneth; Weaver, Casey (2016). Janeway's Immunobiology. Garland Science. ISBN 978-0815342434.

- ↑ Clarindo, Marcos Vinícius; Possebon, Adriana Tomazzoni; Soligo, Emylle Marlene; Uyeda, Hirofumi; Ruaro, Roseli Terezinha; Empinotti, Julio Cesar; Clarindo, Marcos Vinícius; Possebon, Adriana Tomazzoni; Soligo, Emylle Marlene (December 2014). "Dermatitis herpetiformis: pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 89 (6): 865–877. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142966. ISSN 0365-0596.

- ↑ Bolotin, Diana; Petronic-Rosic, Vesna (2011). "Dermatitis herpetiformis". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 64 (6): 1017–1024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.09.777.

- ↑ "What's The Diagnosis #9". Emergency Physicians Monthly. Retrieved 27 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Dermatitis herpetiformis". DermNet NZ.

- ↑ Korossy SK (2010). "Non-Dermatitis Herpetiformis Gluten-Sensitive Dermatitis: A Personal Account of an Unrecognized Entity". Cutis. 86 (6): 285–286. PMID 21284279.

- ↑ Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Haines M, Doecke, JD, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG, Gibson PR; Newnham; Irving; Barrett; Haines; Doecke; Shepherd; Muir; Gibson (2011). "Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 106 (3): 508–514. doi:10.1038/ajg.2010.487. PMID 21224837.

- ↑ ""Dapsone"". Dermatology Online Journal.

- ↑ Ciacci C, Ciclitira P, Hadjivassiliou M, Kaukinen K, Ludvigsson JF, McGough N, Sanders DS, Woodward J, Leonard JN, Swift GL (2015). "The gluten-free diet and its current application in coeliac disease and dermatitis herpetiformis". United European Gastroenterology Journal. 3 (2): 121–135. doi:10.1177/2050640614559263. PMC 4406897. PMID 25922672.

- ↑ "Herpetiformis Dermatitis Effects And Complications". Retrieved 2010-06-23.

- ↑ Reunala, T; Collin, P (1997). "Diseases associated with dermatitis herpetiformis". The British Journal of Dermatology. 136 (3): 315–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14935.x. PMID 9115907.

- ↑ Jelinek JE (1979). "Jean-Paul Marat: The differential diagnosis of his skin disease". American Journal of Dermatopathology. 1 (3): 251–2. doi:10.1097/00000372-197900130-00010. PMID 396805.

Further reading

- Kárpáti S (2012). "Dermatitis herpetiformis". Clinics in Dermatology (Review). 30 (1): 56–9. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.03.010. PMID 22137227.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Pictures: DermNet NZ

- Pictures: The Gastrolab Image Library

- Large and varied collection of DH photos at University of Iowa's Hardin Library for the Health Sciences

- DermNet immune/dermatitis-herpetiformis