Sanjak of Novi Pazar

| Sanjak of Novi Pazar Yeni Pazar sancağı (Turkish) | |||||

| Sanjak of the Ottoman Empire | |||||

| |||||

.png) | |||||

| Capital | Novi Pazar | ||||

| History | |||||

| • | Sanjak of Novi Pazar created | 1865 | |||

| • | New Sanjak of Pljevlja created | 1880 | |||

| • | Sanjak of Sjenica created by reorganization | 1902 | |||

| • | Region partitioned after the First Balkan War | 1912 | |||

| Today part of | |||||

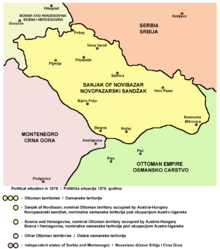

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar (Serbo-Croatian: Novopazarski sandžak; Serbian Cyrillic: Новопазарски санџак; Turkish: Yeni Pazar sancağı) was an Ottoman sanjak (second-level administrative unit) that was created in 1865. It was reorganized in 1880 and 1902. The Ottoman rule in the region lasted until the First Balkan War (1912). Sanjak of Novi Pazar included territories of present-day northeastern Montenegro and southwestern Serbia, also including some northern parts of Kosovo.[a] The region is known as Raška, and also called Sandžak.

History

Background: Ottoman conquest of the Raška region

During the Middle Ages, region of Raška was one of the central regions of Medieval Serbia. Incursions of Ottoman Turks into this region started in late 14th century, after Battle of Kosovo (1389) and the creation of Turkish frontier march (Serbo-Croatian: krajište) of Skopje (1392). Final conquest of Raška region occurred in 1455, when Isa-Beg Isaković, Turkish governor of Skopje, captured the south-western parts of the Serbian Despotate.[1]

At first, region of Raška was included into frontier march of Skopje, and its governor Isa-Beg Isaković decided to create a new stronghold near the old marketplace of Staro Trgovište (Turkish: Eski Pazar, literally meaning "old market place"). New site (Serbo-Croatian: Novo Trgovište) was therefore called Novi Pazar (Turkish: Yeni Pazar, meaning "new market place"). Isaković built a mosque there, and also a public bath, a hostel, and a compound.[2] Novi Pazar initially belonged to the Jeleč vilayet of the Skopsko Krajište ("Skopje Frontier March").[3] There were also the vilayets of Ras and Sjenica.[3] By 1463, the region was incorporated into the newly created Sanjak of Bosnia. The seat of the kadı was subsequently transferred from Jeleč to Novi Pazar little before 1485, and since that time the city became most important center in southeastern parts of Bosnian Sanjak.[4] Region of Novi Pazar remained part of the Sanjak of Bosnia until 1864.

Establishment of the Sanjak of Novi Pazar

Following the promulgation of the Vilayet Law in 1864, and the reorganization of the Eyalet of Bosnia in 1865, region of Novi Pazar became a separate Sanjak with its administrative seat in the city of Novi Pazar. Initially, it had "kazas" (districts) of Yenivaroş, Mitroviça, Gusinye, Trgovište, Akova, Kolaşin, Prepol and Taşlıca. Sanjak of Novi Pazar belonged to he Vilayet of Bosnia, prior to becoming a part of the newly established Kosovo Vilayet in 1878. It included most of the present day Sandžak region (named after the Sanjak of Novi Pazar), also called Raška, as well as northeastern parts of Montenegro and some northern parts of Kosovo (area around Kosovska Mitrovica).

Congress of Berlin (1878)

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Andrássy, in addition to the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, also obtained the right to station garrisons in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, which remained under Ottoman administration. The Sanjak preserved its separation of Serbia and Montenegro, and the Austro-Hungarian garrisons there would open the way for a dash to Salonika that "would bring the western half of the Balkans under permanent Austrian influence."[5] "High [Austro-Hungarian] military authorities desired [an ...] immediate major expedition with Salonika as its objective." [6]

On 28 September 1878 the Finance Minister, Koloman von Zell, threatened to resign if the army, behind which stood the Archduke Albert, were allowed to advance to Salonika. In the session of the Hungarian Parliament of 5 November 1878 the Opposition proposed that the Foreign Minister should be impeached for violating the constitution by his policy during the Near East Crisis and by the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The motion was lost by 179 to 95. By the Opposition rank and file the gravest accusations were raised against Andrassy.[6]

On 10 October 1878 the French diplomat Melchior de Vogüé described the situation as follows:

Particularly in Hungary the dissatisfaction caused by this "adventure" has reached the gravest proportions, prompted by that strong conservative instinct which animates the Magyar race and is the secret of its destinies. This vigorous and exclusive instinct explains the historical phenomenon of an isolated group, small in numbers yet dominating a country inhabited by a majority of peoples of different races and conflicting aspirations, and playing a role in European affairs out of all proportions to its numerical importance or intellectual culture. This instinct is to-day awakened and gives warning that it feels the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina to be a menace which, by introducing fresh Slav elements into the Hungarian political organism and providing a wider field and further recruitment of the Croat opposition, would upset the unstable equilibrium in which the Magyar domination is poised.[7]

This Austro-Hungarian expansion southward at the expense of the Ottoman Empire was designed to prevent the extension of Russian influence and the union of Serbia and Montenegro.

Ottoman administrative changes

.jpg)

In order to counter the Austro-Hungarian influence in the region of Raška, the Ottoman government made a new administrative change: the Sanjak of Novi Pazar was removed from the Bosnia Vilayet and joined into the Kosovo Vilayet that was established in 1877.[8][9] Soon after that, new administrative changes were made. In 1880, entire western part of Novi Pazar Sanjak was reorganized and on that territory a separate Sanjak of Pljevlja was established, which included the kaza (districts) of Pljevlja (its seat), Prijepolje, and the mundirate (branch office) in Priboj; these were places where Austro-Hungarian garrisons were located.[8]

Another important administrative change was made in 1902, when kaza (district) of Novi Pazar was transferred to the jurisdiction of Sanjak of Priština, and the rest of the Novi Pazar Sanjak was reorganized as the Sanjak of Sjenica, which included the districts of Sjenica (its seat), Nova Varoš, Bijelo Polje and Lower Kolašin (part of modern Bijelo Polje and Mojkovac municipalities).[8] This move was not welcomed by local Slavic Muslims of Novi Pazar, since they saw it as a demonstration of disrespect and mistrust by central Ottoman authorities. After the Turkish Revolution in 1908, some democratic changes were introduced into the local political life, allowing the participation of non-Muslim leaders (Christian and Jewish) in local administrative bodies (mejlis).

Withdrawal of Austro-Hungarian garrisons in 1908

At the beginning of 1908, Austria-Hungary announced intentions to build a railway through the Sanjak towards Ottoman Macedonia, which caused an international uproar. However, in negotiations with Russia the Austro-Hungarians indicated they would be willing to vacate the sanjaks of Pljevlja and Sjenica in exchange for recognition of the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina.[10] The Austro-Hungarian garrisons were withdrawn from the region in 1908, following Austria-Hungary's formal annexation of the neighboring Ottoman vilayet of Bosnia, which also belonged (de jure) to the Ottoman Empire until 1908, but was under Austro-Hungarian military occupation since the Treaty of Berlin in 1878.

Balkan Wars (1912–1913) and the end of Ottoman rule

In the aftermath of the Ottoman defeat during the First Balkan War of 1912–1913, the territory of the Ottoman sanjaks of Pljevlja, Sjenica and Priština were divided between Serbia and Montenegro at the Treaty of London in 1913, region of Pljevlja becoming part of Montenegro and regions of Sjenica and Novi Pazar with rest of the Priština Sanjak became parts of Serbia.

Population

The Sanjak of Novi Pazar was mainly populated by Slavic Muslims (Islamized South Slavs, Slavized Muslim Albanians), Serbs (Eastern Orthodox Christians), and some Albanian Muslims and Turks.

Cities

Some important cities in the sanjak were: (Ottoman names in parenthesis).

- Novi Pazar (Yenipazar)

- Sjenica (Seniça)

- Prijepolje (Prepol)

- Nova Varoš (Yenivaroş)

- Priboj (Priboy)

- Kosovska Mitrovica (Mitroviça, Metrofçe)

- Pljevlja (Taşlıca)

- Bijelo Polje (Akova)

- Berane (Berane)

- Rožaje (Rozaje)

References in popular culture

In Saki's 1910 short story "The Lost Sanjak", the plot turns on the protagonist's ability to remember the location of Novi Pazar.

"The Sanjak of Novi Pazar" is a song in the 1973 novel Gravity's Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon.

The Sanjak of Novipazar was an American band, inspired by fellow parody-rock acts, The Fugs and The Mothers of Invention. The Sanjac of Novipazar was led by pianists Deborah Greene and Tobias Mostel, and supported by drummer Tony Bartoli, bassist Jeff di Lorenzo, and guitarists Jerry Blaine, Bruno Blaine, and Mikey Push. From 1967-1968, The Sanjak of Novipazar frequented WBAI's Bob Fass show and small venues throughout New York City. The group performed at the Woodstock Sound-Outs festival in 1968.

See also

Notes and references

Notes:

| a. | ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received formal recognition as an independent state from 113 out of 193 United Nations member states. |

References:

- ↑ Ćirković 2004, pp. 23, 107, 111.

- ↑ Mihailo Maletić (1969). Novi Pazar i okolina. Književne novine. p. 107. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

Ако се (1455) помињу села Поток и Парице, а град не, то би значило да му још тада нису били ударени темељи. Изгледа ца се Иса-бег Исхаковић одлучио на изградњу града-утврђен>а већ 1456. године када имамо прве помене о Новом Пазару

- 1 2 Katić, Tatjana (2010), "Vilajet Pastric (Paštrik) 1452/1453 godine", Micelleanea (in Serbian), Belgrade: Istorijski Institut

- ↑ Hazim Šabanović (1959). Bosanski pašaluk: postanak i upravna podjela. Naučno društvo NR Bosne i Hercegovine. p. 118. Retrieved 27 January 2013.

središta iz Jeleča u Novi Pazar izvršeno svakako nešto prije 1485 g., kada je Jeleč već bio izgubio raniji strateški značaj, a Novi Pazar, kome je Isa-beg Ishaković udario temelje još šezdesetih godina XV st. razvio se dotle u veću varoš.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (1952). The Origins of the War of 1914. Volume I. Oxford University Press. p. 19.

- 1 2 Albertini, Luigi (1952). The Origins of the War of 1914. Volume I. Oxford University Press. p. 33.

- ↑ Albertini, Luigi (1952). The Origins of the War of 1914. Volume I. Oxford University Press. pp. 33–34.

- 1 2 3 Milić F. Petrović (1995). Dokumenti o Raškoj oblasti: 1900-1912. Arhiv Srbije. p. 8.

Да би сузбила аустроугарски утицај у западним крајевима Рашке области, Турска је извршила нову управну поделу. Новопазарски санџак је 1879. год. издвојен из Босанског вилајста и прикључен Косовеком вилајету, који је основан још 1877. год. са седиштем у Приштини а касније у Скопљу. Потом је 1880. године основан пљеваљ- ски санџак — мутесарифлук тј. округ саседиштем у Пљевљима, који је обухватио казе Пљевља, Пријеноље и мундирлук - испоставу у Прибоју. Тосу места у којимасу се налазили аустро-угарски гарнизони. Исте године формиран је Новопазарски, одно- сно Сјенички санџак са седиштем у Сјеници, а који је обухватио казе: сјеничку, нововарошку, бјелопољску и доњоколашинску (територија данашњих општина Би- јело Поље и ...

- ↑ Dragoslav Srejović; Slavko Gavrilović; Sima M. Ćirković (1983). Istorija srpskog naroda: knj. Od Berlinskog kongresa do Ujedinjenja 1878-1918 (2 v.). Srpska književna zadruga. p. 263.

Новопазарски санџак је већ 1879. издвојен из босанског вилајета са седиштем у Сарајеву и припојен косовском вилајету који је основан 30. јануара 1877. са седиштем у Приштини.

- ↑ MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace. Random House. pp. 420–423.

Literature

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983a). History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1983b). History of the Balkans: Twentieth Century. 2. Cambridge University Press.

- Ağanoğlu, Yıldırım (2000). Salnâme-i Vilâyet-i Kosova: Yedinci defa olarak vilâyet matbaasında tab olunmuştur: 1896 (hicri 1314) Kosova vilâyet-i salnâmesi (Üsküp, Priştine, Prizren, İpek, Yenipazar, Taşlıca). İstanbul: Rumeli Türkleri Kültür ve Dayanışma Derneği.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Dragica Premović-Aleksić, Islamski spomenici Novog Pazara (Islamic Monuments in Novi Pazar), Novi Pazar 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sanjak of Novi Pazar. |