Antarctic Circumpolar Current

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) is an ocean current that flows clockwise from west to east around Antarctica. An alternative name for the ACC is the West Wind Drift. The ACC is the dominant circulation feature of the Southern Ocean and has a mean transport estimated at 100-150 Sverdrups (Sv, million m³/s),[1] or possibly even higher,[2] making it the largest ocean current. The current is circumpolar due to the lack of any landmass connecting with Antarctica and this keeps warm ocean waters away from Antarctica, enabling that continent to maintain its huge ice sheet.

Associated with the Circumpolar Current is the Antarctic Convergence, where the cold Antarctic waters meet the warmer waters of the subantarctic, creating a zone of upwelling nutrients. These nurture high levels of phytoplankton with associated copepods and krill, and resultant foodchains supporting fish, whales, seals, penguins, albatrosses, and a wealth of other species.

The ACC has been known to sailors for centuries; it greatly speeds up any travel from west to east, but makes sailing extremely difficult from east to west; although this is mostly due to the prevailing westerly winds. The circumstances preceding the mutiny on the Bounty and Jack London's story "Make Westing" poignantly illustrated the difficulty it caused for mariners seeking to round Cape Horn on the clipper ship route between New York and California.[3] The clipper route, which is the fastest sailing route around the world, follows the ACC around three continental capes – Cape Agulhas (Africa), South East Cape (Australia), and Cape Horn (South America).

The current creates the Ross and Weddell gyres.

Structure

The ACC connects the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, and serves as a principal pathway of exchange among them. The current is strongly constrained by landform and bathymetric features. To trace it starting arbitrarily at South America, it flows through the Drake Passage between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula and then is split by the Scotia Arc to the east, with a shallow warm branch flowing to the north in the Falkland Current and a deeper branch passing through the Arc more to the east before also turning to the north. Passing through the Indian Ocean, the current first retroflects the Agulhas Current to form the Agulhas Return Current before it is split by the Kerguelen Plateau, and then moving northward again. Deflection is also seen as it passes over the mid-ocean ridge in the Southeast Pacific.

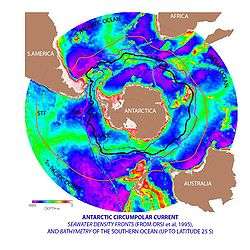

Fronts

The current is accompanied by three fronts: the Subantarctic front (SAF), the Polar front (PF), and the Southern ACC front (SACC).[4] Furthermore, the waters of the Southern Ocean are separated from the warmer and saltier subtropical waters by the subtropical front (STF).[5]

The northern boundary of the ACC is defined by the northern edge of the SAF, this being the most northerly water to pass through Drake Passage and therefore be circumpolar. Much of the ACC transport is carried in this front, which is defined as the latitude at which a subsurface salinity minimum or a thick layer of unstratified Subantarctic mode water first appears, allowed by temperature dominating density stratification. Still further south lies the PF, which is marked by a transition to very cold, relatively fresh, Antarctic Surface Water at the surface. Here a temperature minimum is allowed by salinity dominating density stratification, due to the lower temperatures. Farther south still is the SACC, which is determined as the southernmost extent of Circumpolar Deep Water (temperature of about 2 °C at 400 m). This water mass flows along the shelfbreak of the western Antarctic Peninsula and thus marks the most southerly water flowing through Drake Passage and therefore circumpolar. The bulk of the transport is carried in the middle two fronts.

The total transport of the ACC at Drake Passage is estimated to be around 135 Sv, or about 135 times the transport of all the world's rivers combined. There is a relatively small addition of flow in the Indian Ocean, with the transport south of Tasmania reaching around 147 Sv, at which point the current is probably the largest on the planet.

Dynamics

The circumpolar current is driven by the strong westerly winds in the latitudes of the Southern Ocean.

In latitudes where there are continents, winds blowing on light surface water can simply pile up light water against these continents. But in the Southern Ocean, the momentum imparted to the surface waters cannot be offset in this way. There are different theories on how the Circumpolar Current balances the momentum imparted by the winds. The increasing eastward momentum imparted by the winds causes water parcels to drift outward from the axis of the Earth's rotation (in other words, northward) as a result of the Coriolis force. This northward Ekman transport is balanced by a southward, pressure-driven flow below the depths of the major ridge systems. Some theories connect these flows directly, implying that there is significant upwelling of dense deep waters within the Southern Ocean, transformation of these waters into light surface waters, and a transformation of waters in the opposite direction to the north. Such theories link the magnitude of the Circumpolar Current with the global thermohaline circulation, particularly the properties of the North Atlantic.

Alternatively, ocean eddies, the oceanic equivalent of atmospheric storms, or the large-scale meanders of the Circumpolar Current may directly transport momentum downward in the water column. This is because such flows can produce a net southward flow in the troughs and a net northward flow over the ridges without requiring any transformation of density. In practice both the thermohaline and the eddy/meander mechanisms are likely to be important.

The current flows at a rate of about 4 km/h (2.5 mph) over the Macquarie Ridge south of New Zealand.[6] The ACC varies with time. Evidence of this is the Antarctic Circumpolar Wave, a periodic oscillation that affects the climate of much of the southern hemisphere.[7] There is also the Antarctic oscillation, which involves changes in the location and strength of Antarctic winds. Trends in the Antarctic Oscillation have been hypothesized to account for an increase in the transport of the Circumpolar Current over the past two decades.

Formation

Published estimates of the onset of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current vary, but it is commonly considered to have started at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary. The isolation of Antarctica and formation of the ACC occurred with the openings of the Tasmanian Seaway and the Drake Passage. The Tasmanian Seaway separates East Antarctica and Australia, and is reported to have opened to water circulation 33.5 Ma.[8] The timing of the opening of the Drake Passage, between South America and the Antarctic Peninsula, is more disputed; tectonic and sediment evidence show that it could have been open as early as pre 34 Ma,[9] estimates of the opening of the Drake passage are between 20 and 40 Ma.[10] The isolation of Antarctica by the current is credited by many researchers with causing the glaciation of Antarctica and global cooling in the Eocene epoch. Oceanic models have shown that the opening of these two passages limited polar heat convergence and caused a cooling of sea surface temperatures by several degrees; other models have shown that CO2 levels also played a significant role in the glaciation of Antarctica.[10][11]

Phytoplankton

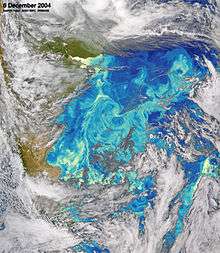

Antarctic sea ice cycles seasonally, in February–March the amount of sea ice is lowest, and in August–September the sea ice is at its greatest extent.[12] Ice levels have been monitored by satellite since 1973. Upwelling of deep water under the sea ice brings substantial amounts of nutrients. As the ice melts, the melt water provides stability and the critical depth is well below the mixing depth, which allows for a positive net primary production.[13] As the sea ice recedes epontic algae dominate the first phase of the bloom, and a strong bloom dominate by diatoms follows the ice melt south.[13]

Another phytoplankton bloom occurs more to the north near the antarctic convergence, here nutrients are present from thermohaline circulation. Phytoplankton blooms are dominated by diatoms and grazed by copepods in the open ocean, and by krill closer to the continent. Diatom production continues through the summer, and populations of krill are sustained, bringing large numbers of cetaceans, cephalopods, seals, birds, and fish to the area.[13]

Phytoplankton blooms are believed to be limited by irradiance in the austral (southern hemisphere) spring, and by biologically available iron in the summer.[14] Much of the biology in the area occurs along the major fronts of the current, the Subtropical, Subantarctic, and the Antarctic Polar fronts, these are areas associated with well defined temperature changes.[15] Size and distribution of phytoplankton are also related to fronts. Microphytoplankton (>20μm) are found at fronts and at sea ice boundaries, while nanophytoplankton (<20μm) are found between fronts.[16]

Studies of phytoplankton stocks in the southern sea have shown that the Antarctic Circumpolar Current is dominated by diatoms, while the Weddell Sea has abundant coccolithophorids and silicoflagellates. Surveys of the SW Indian Ocean have shown phytoplankton group variation based on their location relative to the Polar Front, with diatoms dominating South of the front, and dinoflagellates and flagellates in higher populations North of the front.[16]

Some research has been conducted on Antarctic phytoplankton as a carbon sink. Areas of open water left from ice melt are good areas for phytoplankton blooms. The phytoplankton takes carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis. As the blooms die and sink, the carbon can be stored in sediments for thousands of years. This natural carbon sink is estimated to remove 3.5 million tonnes from the ocean each year. 3.5 million tonnes of carbon taken from the ocean and atmosphere is equivalent to 12.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide.[17]

Studies

An expedition in May 2008 by 19 scientists[18] studied the geology and biology of eight Macquarie Ridge sea mounts, as well as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to investigate the effects of climate change of the Southern Ocean. The circumpolar current merges the waters of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans and carries up to 150 times the volume of water flowing in all of the world's rivers. The study found that any damage on the cold-water corals nourished by the current will have a long-lasting effect.[6] After studying the circumpolar current it is clear that it strongly influences regional and global climate as well as underwater biodiversity.[19]

Dr. Adrian Glover of the Natural History Museum, London says that the current helps preserve wooden shipwrecks by preventing wood-boring "ship worms" from reaching targets such as Ernest Shackleton's ship, the Endurance.[20]

References

Notes

- ↑ Smith et al. 2013

- ↑ Donohue, K.A.; et al. (21 November 2016). "Mean Antarctic Circumpolar Current transport measured in Drake Passage". Geophysical Research Letters. 43 (11): 760. Bibcode:2016GeoRL..4311760D. doi:10.1002/2016GL070319. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- ↑ London 1907

- ↑ Stewart 2007

- ↑ Orsi, Whitworth & Nowlin 1995, Introduction, p.641

- 1 2 "Explorers marvel at 'Brittlestar City' on seamount in powerful current swirling around Antarctica". 18 May 2008. Retrieved 6 June 2008.

- ↑ Connolley 2002

- ↑ Hassold et al. 2009

- ↑ Barker et al. 2007

- 1 2 Siegert et al. 2008

- ↑ Stott 2011, See "Ancient Current Systems" illustrations at bottom of page

- ↑ Geerts 1998

- 1 2 3 Miller 2004, p. 219

- ↑ Peloquin & Smith 2007

- ↑ "The Southern Ocean". GES DISC: Goddard Earth Sciences, Data & Information Services Center. May 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- 1 2 Knox 2007, p. 23

- ↑ Peck et al. 2010

- ↑ O'Hara, Rowden & Williams 2008

- ↑ Rintoul, Hughes & Olbers 2001, e.g. p. 271

- ↑ Glover et al. 2013

Sources

- Barker, P. F.; Filippelli, G. M.; Florindo, F.; Martin, E. E.; Scher, H. D. (2007). "Onset and Role of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current" (PDF). Deep-Sea Research Part II. 54 (21): 2388–2398. Bibcode:2007DSRII..54.2388B. doi:10.1016/j.dsr2.2007.07.028. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Connolley, W. M. (2002). "Long-term variation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Wave". Journal of Geophysical Research. 107 (C4). Bibcode:2002JGRC..107.8076C. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.4116. doi:10.1029/2000JC000380.

- Geerts, B. (1998). "Antarctic sea ice: seasonal and long-term changes". Department of Atmospheric science, University of Wyoming. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Glover, A. G.; Wiklund, H.; Taboada, S.; Avila, C.; Cristobo, J.; Smith, C. R.; Kemp, K. M.; Jamieson, A. J.; Dahlgren, T. G. (2013). "Bone-eating worms from the Antarctic: the contrasting fate of whale and wood remains on the Southern Ocean seafloor". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 280 (1768): 20131390. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.1390. PMC 3757972. PMID 23945684. Lay summary (May 2015).

- Hassold, N. J. C.; Rea, D. K.; Pluijm, B. A., van der; Parés, J. M. (2009). "A physical record of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current: late Miocene to recent slowing of abyssal circulation" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 275: 28–36. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.01.011. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Knox, G. A. (2007). Biology of the Southern Ocean. CRC Marine Biology Series. CRC Press. ISBN 9780849333941.

- London, Jack (1907). "Make Westing". Literature Collection. Archived from the original on 27 January 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Miller, C. B. (2004). Biological Oceanography. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9780632055364.

- O'Hara, T. D.; Rowden, A. A.; Williams, A. (2008). "Cold-water coral habitats on seamounts: do they have a specialist fauna?". Diversity and Distributions. 14 (6): 925–934. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00495.x.

- Orsi, A. H.; Whitworth, T.; Nowlin, W. D., Jr. (1995). "On the meridional extent and fronts of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current" (PDF). Deep-Sea Research. I. 42: 641–673. Bibcode:1995DSRI...42..641O. doi:10.1016/0967-0637(95)00021-W. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Peck, L. S.; Barnes, D. K. A.; Cook, A. J.; Fleming, A. H.; Clarke, A. (2010). "Negative feedback in the cold: ice retreat produces new carbon sinks in Antarctica" (PDF). Global Change Biology. 16 (9): 2614–2623. Bibcode:2010GCBio..16.2614P. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02071.x. Retrieved 29 December 2016. Lay summary (May 2015).

- Peloquin, J. A.; Smith, W. O., Jr. (2007). "Phytoplankton blooms in the Ross Sea, Antarctica: Interannual variability in magnitude, temporal patterns, and composition" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 112 (C08013). Bibcode:2007JGRC..112.8013P. doi:10.1029/2006JC003816. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Rintoul, S. R.; Hughes, C.; Olbers, D. (2001). "The Antarctic Circumpolar Current System" (PDF). In Siedler, G.; Church, J.; Gould, J. Ocean Circulation and Climate. New York: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-641351-7. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Siegert, M. J.; Barrett, P.; Deconto, R. M.; Dunbar, R.; Cofaigh, C. O.; Passchier, S.; Naish, T. (2008). "Recent Advances in Understanding Antarctic Climate Evolution". Antarctic Science. 20 (4): 313–325. Bibcode:2008AntSc..20..313S. doi:10.1017/S0954102008000941. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Smith, R.; Desflots, M.; White, S.; Mariano, A. J.; Ryan, E. H. (2013). "The Antarctic Circumpolar Current". Rosenstiel School of Marine & Atmospheric Science. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Stewart, R. H. (2007). "Deep Circulation in the Ocean: Antarctic Circumpolar Current". Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Stott, L. D. (2011). "Ocean Currents and Climate". Department of Earth Sciences, University of Southern California. Retrieved 29 December 2016.