Cash (Chinese coin)

| Cash | |||||||

|

Replicas of various ancient to 19th century cast cash coins in various metals found in China, Korea and Japan. | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 方孔錢 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 方孔钱 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | square-holed money | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 銅錢 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 铜钱 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | copper money | ||||||

| |||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 銅幣 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 铜币 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | copper currency | ||||||

| |||||||

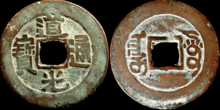

Cash was a type of coin of China and East Asia, used from the 4th century BC until the 20th century AD, characterised by their round outer shape and a square center hole (方穿, fāng chuān). Originally cast during the Warring States period, these coins continued to be used for the entirety of Imperial China as well as under Mongol, and Manchu rule. The last Chinese cash coins were cast in the first year of the Republic of China. Generally most cash coins were made from copper or bronze alloys, with iron, lead, and zinc coins occasionally used less often throughout Chinese history. Rare silver and gold cash coins were also produced. During most of their production, cash coins were cast, but during the late Qing dynasty, machine-struck cash coins began to be made. As the cash coins produced over Chinese history were similar, thousand year old cash coins produced during the Northern Song dynasty continued to circulate as valid currency well into the early twentieth century.[1]

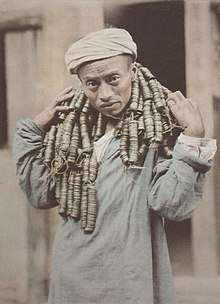

In the modern era, these coins are considered to be Chinese “good luck coins”; they are hung on strings and round the necks of children, or over the beds of sick people. They hold a place in various superstitions, as well as Traditional Chinese medicine, and Feng shui. Currencies based on the Chinese cash coins include the Japanese mon, Korean mun, Ryukyuan mon, and Vietnamese văn.

Terminology

The English term "cash", referring to the coin, was derived from the Tamil kāsu, a South Indian monetary unit. The English word "cash", meaning "tangible currency", is an older and unrelated word, derived from the Middle French caisse.[2]

There are a variety of Chinese terms for cash coins, usually descriptive and most commonly including the character qian (Chinese: 錢; pinyin: qián) meaning "money". Chinese qián is also a weight-derived currency denomination in China; it is called "mace" in English.

Manufacture

Traditionally, Chinese cash coins were cast in copper, brass or iron. In the mid-19th century, the coins were made of 3 parts copper and 2 parts lead.[3] Cast silver coins were periodically produced but considerably more rare. Cast gold coins are also known to exist but are extremely rare.

Early methods of casting

During the Zhou dynasty period, the method for casting coins consisted of first carving the individual characters of a coin together with its general outline into a mould made of either soapstone or clay. As this was done without using a prior model, early Chinese coinage tends to look very diverse, even from the same series of coins as these all were cast from different (and unrelated) moulds bearing the same inscriptions.

During the Han dynasty, in order to gain consistency in the circulating coinage, master bronze moulds were manufactured to be used as the basis for other cash moulds.[4]

Later methods of manufacture

From the 6th century AD and later, new "mother coins" (mǔ qián 母錢) were cast as the basis for coin production. These were engraved in generally easily manipulated metals such as tin. Coins were cast in sand moulds. Fine wet sand was placed in rectangles made from pear wood, and small amounts of coal and charcoal dust were added to refine the process, acting as a flux. The mother coins were placed on the sand, and another pear wood frame would be placed upon the mother coin. The molten metal was poured in through a separate entrance formed by placing a rod in the mould. This process would be repeated 15 times and then molten metal would be poured in. After the metal had cooled down, the "coin tree" (qián shù 錢樹) was extracted from the mould (which would be destroyed due to the process). The coins would be taken off the tree and placed on long square rods to have their edges rounded off, often for hundreds of coins simultaneously. After this process, the coins were strung together and brought into circulation.

From 1730 during the Qing dynasty, the mother coins were no longer carved separately but derived from "ancestor coins" (zǔ qián 祖錢). Eventually this resulted in greater uniformity among cast Chinese coinage from that period onwards. A single ancestor coin would be used to produce tens of thousands of mother coins; each of these in turn was used to manufacture tens of thousands of cash coins.[5][6][7]

Machine-struck coinage

_-_Boo_Guwang_(%E1%A0%AA%E1%A0%A3%E1%A0%A3_%E1%A1%A4%E1%A1%A0%E1%A0%B8%E1%A0%A0%E1%A0%A9)_Guangzhou_Mint_-_Machine-struck_07.jpg)

During the late Qing dynasty under the reign of the Guangxu Emperor in the mid 19th century the first machine-struck cash coins were produced, from 1889 a machine operated mint in Guangzhou, Guangdong province opened where the majority of the machine-struck cash would be produced. Machine-made cash coins tend to be made from brass rather than from more pure copper as cast coins often were, and later the copper content of the alloy decreased while cheaper metals like lead and tin were used in larger quantities giving the coins a yellowish tint. Another effect of the contemporary copper shortages was that the Qing government started importing Korean 5 fun coins and overstruck them with "10 cash".[8][9]

History

.jpg)

Chinese cash coins originated from the barter of farming tools and agricultural surpluses.[10] Around 1200 BC, smaller token spades, hoes, and knives began to be used to conduct smaller exchanges with the tokens later melted down to produce real farm implements. These tokens came to be used as media of exchange themselves and were known as spade money and knife money.[11]

As standard circular coins were developed following the unification of China by Qin Shi Huang, the most common formation was the round-shaped copper coin with a square or circular hole in the center, the prototypical cash. The early Ban Liang coins were said to have been made in the shape of wheels like how other Ancient Chinese forms of coinage were based on agricultural tools. The hole enabled the coins to be strung together to create higher denominations, as was frequently done due to the coin's low value. The number of coins in a string of cash (simplified Chinese: 一贯钱; traditional Chinese: 一貫錢; pinyin: yīguànqián) varied over time and place but was nominally 1000. A string of 1000 cash was supposed to be equal in value to one tael of pure silver.[11] A string of cash was divided into ten sections of 100 cash each. Local custom allowed the person who put the string together to take a cash or a few from each hundred for his effort (one, two, three or even four in some places). Thus an ounce of silver could exchange for 970 in one city and 990 in the next. In some places in the North of China short of currency the custom counted one cash as two and fewer than 500 cash would be exchanged for an ounce of silver. A string of cash weighed over ten pounds and was generally carried over the shoulder. (See Hosea Morse's "Trade and Administration of the Chinese Empire" p. 130 ff.) Paper money equivalents known as flying cash sometimes showed pictures of the appropriate number of cash coins strung together.[12]

The Koreans,[13] Japanese,[14] Ryukyuans,[15] and Vietnamese[16][17] all cast their own copper cash in the latter part of the second millennium similar to those used by China.[18]

Almost the last Chinese cash coins were struck, not cast, in the reign of the Qing Xuantong Emperor shortly before the fall of the Empire in 1911, though even after the fall of the Qing dynasty production briefly continued under the Republic of China with the "Min Guo Tong Bao" (民國通寶) coins in 1912, and under Yuan Shikai's Empire of China with the "Hong Xiang Tong Bao" (洪憲通寶) series in 1916.[19] The coin continued to be used unofficially in China until the mid-20th century. Vietnamese cash continued to be cast up until the early 1940s.[20]

Cash coins in the early Republic of China

.png)

During the early Republican era a few more cash coins were locally produced until they were finally phased out in favour of the new yuan.

| Inscription (Obverse, Reverse) | Traditional Chinese (Obverse, Reverse) | Simplified Chinese (Obverse, Reverse) | Issuing office |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fujian Tong Bao, 1 cash | 福建通寶, 一文 | 福建通宝, 一文 | Fujian province |

| Fujian Tong Bao, 2 cash | 福建通寶, 二文 | 福建通宝, 二文 | Fujian province |

| Min Guo Tong Bao, Dongchuan | 民國通寶, 東川 | 民国通宝, 东川 | Dongchuan, Yunnan |

| Min Guo Tong Bao, 10 cash | 民國通寶, 當十 | 民国通宝, 当十 | Dongchuan, Yunnan |

Trial coins with Fujian Sheng Zao (Chinese: 福建省造), Min Sheng Tong Yong (traditional Chinese: 閩省通用; simplified Chinese: 闽省通用), and a Fujian Tong Bao with a reverse inscribed with Er Wen Sheng Zao (Chinese: 二文省造) were also cast, but never circulated.[23]

Inscriptions and denominations

The earliest standard denominations of cash coins were theoretically based on the weight of the coin and were as follows:

- 100 grains of millet = 1 zhu (Chinese: 銖; pinyin: zhū)

- 24 zhū = 1 tael (Chinese: 兩; pinyin: liǎng)

The most common denominations were the ½ tael (Chinese: 半兩; pinyin: bànliǎng) and the 5 zhū (Chinese: 五銖; pinyin: wǔ zhū) coins, the latter being the most common coin denomination in Chinese history.[11]

From the Zhou to the Tang dynasty the word quán (泉) was commonly used to refer to cash coins however this wasn't a real monetary unit but did appear in the inscriptions of several cash coins, in the State of Yan their cash coins were denominated in either huà (化) or huò (貨) with the Chinese character "化" being a simplified form of "貨" minus the "貝". This character was often mistaken for dāo (刀) due to the fact that this early version of the character resembles it and Knife money was used in Yan, however the origin of the term huò as a currency unit is because it means "to exchange" and could be interpreted as exchanging money for goods and services.[24][25] From the Jin until the Tang dynasty the term wén (文), however the term wén which is often translated into English as "cash" kept being used as an accounting unit for banknotes and later on larger copper coins to measure how many cash coins it was worth.[26]

In AD 666, a new system of weights came into effect with the zhū being replaced by the mace (qián) with 10 mace equal to one tael. The mace denominations were so ubiquitous that the Chinese word qián came to be used as the generic word for money.[11] Other traditional Chinese units of measurement, smaller subdivisions of the tael, were also used as currency denominations for cash coins.

A great majority of cash coins had no denomination specifically designated but instead carried the issuing emperor's era name and a phrases such as tongbao (Chinese: 通寶; pinyin: tōngbǎo; literally: "general currency") or zhongbao (Chinese: 重寶; pinyin: zhòngbǎo; literally: "heavy currency").

Coins of the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) generally carried the era name of the emperor and tongbao on the obverse and the mint location where the coins were cast in Manchu and Chinese on the reverse.[27]

Cash coins and superstitions

In Imperial China cash coins were used for fortune-telling, this would be done by first lighting incense to the effigy of a Chinese deity, and then placing 3 cash coins into a tortoise shell. The process involved the fortune teller counting how many coins lay on their obverse or reverse sides, and how these coins scratched the shell, this process was repeated 3 times. After this a very intricate system based on the position of the coins with Bagua, and the Five elements would be used for divination, the Tang dynasty Kai Yuan Tong Bao (開元通寶) coin was the most preferred coin for this usage. Contemporary Chinese intelligentsia found the usage of cash coins for fortune-telling to be superior than any other methods.[28][29] Other than fortune-telling cash coins were also believed to hold “curing powers” in Traditional Chinese medicine, one method of using cash coins for “medicine” was boiling them in water and let the patient consume that water. Other than that they were also used as “medical tools” particularly in the guāshā (刮痧) method, which was used against diseases like Cholera; this required the healer to scrape the patient’s skin with cash coins as they believed that the pathogen remained stagnant underneath the patient’s skin in a process called “coining”. Though in general any cash coin could be used in traditional Chinese medicine but the Kai Yuan Tong Bao was most preferred, and preferences were given for some specific coins for certain ailments E.g. the Zhou Yuan Tong Bao (周元通寶) was used against miscarriages.[30][31][32]

In modern times though no longer issued by any government, cash coins are believed to be symbols of good fortune and are considered “Good luck charms”, for this reason some businesses hang Chinese cash coins as store signs for “good luck” and to allegedly avoid misfortune similar to how images of Caishen (the Chinese God of Wealth) are used.[33] Cash coins also hold a central place in Feng shui where they are associated an abundance of resources, personal wealth, money, and prosperity. Cash coins are featured on the logos of the Bank of China, and the China Construction Bank.[34][35]

In Bali it is believed that dolls made from cash coins (or Uang kèpèng) strung together by cotton threads would guarantee that all the organs and body parts of the deceased will be in the right place during their reincarnation.[36][37] The Tlingit people of the United States of America and Canada used Chinese cash coins for their body armour which they believed would protect them from knife attacks and bullets. One contemporary Russian account from a battle with the Tlingits in 1792 states "bullets were useless against the Tlingit armour", however this would've more likely be attributed to the inaccuracy of contemporary Russian smoothbore muskets than the body armour and the Chinese cash coins sewn into the Tlingit armour. Other than for military purposes the Tlingit used Chinese cash coins on ceremonial robes.[38][39][40][41][42]

Stringing of cash coins

The square hole in the middle of cash coins served to allow for them to be strung together in strings of 1000 cash coins and valued at 1 tael of silver (but variants of regional standards as low as 500 cash coins per string also existed),[43] 1000 coins strung together were referred to as a chuàn (串) or diào (吊) and were accepted by traders and merchants per string because counting the individual coins would cost too much time. Because the strings were often accepted without being checked for damaged coins and coins of inferior quality and copper-allots these strings would eventually be accepted based on their nominal value rather than their weight, this system is comparable to that of a fiat currency. Because the counting and stringing together of cash coins was such a time consuming task people known as qiánpù (錢鋪) would string cash coins together in strings of 100 coins of which ten wouldn form a single chuàn. The qiánpù would receive payment for their services in the form of taking a few cash coins from every string they composed, because of this a chuàn was more likely to consist of 990 coins rather than 1000 coins and because the profession of qiánpù had become a universally accepted practice these chuàns were often still nominally valued at 1000 cash coins.[44][45] The number of coins in a single string was locally determined as in one district a string could consist of 980 cash coins, while in another district this could only be 965 cash coins, these numbers were based on the local salaries of the qiánpù.[46][47][48] During the Qing dynasty the qiánpù would often search for older and rarer coins to sell these to coin collectors at a higher price.

Prior to the Song dynasty strings of cash coins were called guàn (貫), suǒ (索), or mín (緡), while during the Ming and Qing dynasties they were called chuàn (串) or diào (吊).[49][50]

Cash coins with flower (rosette) holes

.jpg)

Chinese cash coins with flower (rosette) holes (Traditional Chinese: 花穿錢) are a type of Chinese cash coin with an octagonal hole as opposed to a square one, they have a very long history possibly dating back to the first Ban Liang cash coins cast under the State of Qin or the Han dynasty.

Although Chinese cash coins kept their round shape with a square hole from the Warring States period until the early years of the Republic of China, under the various regimes that ruled during the long history of China the square hole in the middle experienced only minor modifications such as being slightly bigger, smaller, more elongated, shaped incorrectly, or sometimes being filled with a bit of excess metal left over from the casting process. However for over 2000 years Chinese cash coins mostly kept their distinctive shape. During this period a relatively small number of Chinese cash coins were minted with what are termed "flower holes", "chestnut holes" or "rosette holes", these holes were octagonal but resembled the shape of flowers. If the shape of these holes were only hexagonal then they were referred to as "turtle shell holes", in some occidental sources they may be called "star holes" because they resemble stars. The exact origin and purpose of these variant holes is currently unknown but several hypotheses have been proposed by Chinese scholars. The traditional explanation for why these "flower holes" started appearing was accidental shifts of two halves of a prototype cash coin in clay, bronze, and stone moulds, these shifts would then produce the shape of the square hole to resemble multiple square holes placed on top of each other when the metal was poured in. A common criticism of this hypothesis is that if this were to happen then the inscription on the coin would also have to appear distorted, as well as any other marks that appeared on these cash coins, however this was not the case and the "flower holes" are equally distinctive as the square ones.

Under Wang Mang's Xin dynasty other than cash coins with "flower holes" also spade money with "flower holes" were cast. Under the reign of the Tang dynasty the number of Chinese cash coins with "flower holes" started to increase and circulated throughout the entire empire, concurrently the casting of Chinese cash coins was switched from using clay moulds to using bronze ones, however the earliest Kaiyuan Tongbao cash coins were still cast with clay moulds so the mould type alone cannot explain why these "flower holes" became increasingly common. As mother coins (母錢) were used to cast these coins which were always exact it indicates that these "flower holes" were added post-casting, the largest amount of known cash coins with "flower holes" have very prominent octagonal holes in the middle on both sides of the coin, comparatively their legends are usually as defined as they appear on "normal cash coins", for this reason the hypothesis that they were accidentally added is disproven. All sides of these coins (either octagonal with "flower holes" or hexagonal with "turtle shell holes") are clearly contained inside of the cash coin's central rim. After the casting of cash coins had shifted to using bronze moulds these coins would appear as if they were branches of a "coin tree" (錢樹) where they had to be broken off, all excess copper-alloy had to be manually chiseled or filed off from the central holes. It is suspected that the "flower holes" and "turtle shell holes" were produced during chiseling process, presumably while the employee of the manufacturing mint was doing the final details of the cash coins. As manually filing and chiseling cash coins was both an additional expense as well as time-consuming it is likely that the creation of "flower holes" and "turtle shell holes" was ordered by the manufacturer. However as the quality of Tang and Song dynasty coinages was quite high it's unlikely that the supervisors would have allowed for a large number of these variant coins to be produced, pass quality control or be allowed to enter circulation. Cash coins with "flower holes" were produced in significant numbers by the Northern Song dynasty, Southern Song dynasty, and Khitan Liao dynasty. Until 1180 the Northern Song dynasty produced "matched cash coins" (對錢, duì qián) which were cash coins with identical inscriptions written in different styles of Chinese calligraphy, after these coins were superseded by cash coins that included the year of production on their reverse sides the practice of casting cash coins with "flower holes" also seems to have drastically decreased. Due to this one hypothesis states that "flower holes" were added to Chinese cash coins to signify a year or period of the year or possibly a location where a cash coin was produced.

It is also possible that these "flower holes" and "turtle shell holes" functioned as Chinese numismatic charms, this is because the number 8 (八, bā) is a homophonic pun in Mandarin Chinese with "to prosper" or "wealth" (發財, fā cái), while the number 6 (六, liù) is a Mandarin Chinese homophonic pun with "prosperity" (祿, lù). Concurrently the Mandarin Chinese word for as "chestnut" (栗子, lì zi) as in the term "chestnut holes" could be a homophonic pun in Mandarin Chinese with the phrase "establishing sons" (立子, lì zi), which expresses a desire to produce male offspring.

The practice of creating cash coins with "flower holes" and "turtle shell holes" was also adopted by Japan, Korea, and Vietnam, however cash coins with these features are extremely rare in these countries despite using the same production techniques which further indicates that their addition was wholly intentional.[51][52][53][54][55]

Red cash coins

"Red cash coins" (Traditional Chinese: 紅錢) are the cash coins produced in Xinjiang under Qing rule following the conquest of the Dzungar Khanate by the Manchus in 1757. While in Northern Xinjiang the monetary system of China proper was adopted in Southern Xinjiang where the pūl (ﭘول) coins of Dzungaria circulated earlier the pūl-system was continued but some of the old Dzungar pūl coins were melted down to make Qianlong Tongbao (乾隆通寶) cash coins, as pūl coins were usually around 98% copper they tended to be very red in colour which gave the cash coins based on the pūl coins the nickname "red cash coins". In July 1759 General Zhao Hui petitioned to the Qianlong Emperor to reclaim the old pūl coins and using them as scrap for the production of new cash coins, these "red cash coins" had an official exchange rate with the pūl coins that remained in circulation of 1 "red cash" for 2 pūl coins. As Zhao Hui wanted the new can coins to have the same weight as pūl coins they weighed 2 qián and had both a higher width and thickness than regular cash coins. Red cash coins are also generally marked by their rather crude craftsmanship when compared to the cash coins of China proper. The edges of these coins are often not filed completely and the casting technique is often inaccurate or the inscriptions on them seemed deformed.

At the introduction of red cash system in Southern Xinjiang in 1760, the exchange rate of standard cash (or "yellow cash") and "red cash" was set at 10 standard cash coins were worth 1 "red cash coin". During two or three subsequent years this exchange rate was decreased to 5:1. When used in the Northern or Eastern circuits of Xinjiang, the "red cash coins" were considered equal in value as the standard cash coins that circulated there. The areas where the Dzungar pūls had most circulated such as Yarkant, Hotan, and Kashgar were the sites of mints operated by the Qing government, as the official mint of the Dzungar Khanate was in the city of Yarkent the Qing used this mint to cast the new "red cash coins" and new mints were established in Aksu and Ili. As the Jiaqing Emperor ordered that 10% of all cash coins cast in Xinjiang should bear the inscription "Qianlong Tongbao" the majority of "red cash coins" with this inscription were actually produced after the Qianlong era as their production lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 making many of them hard to attribute.[56]

Other terms relating to cash coins

- Mother coins (母錢), are model cash coins used in the casting process from which other cash coins were produced.

- Ancestor coins (祖錢), are model cash coins introduced in the Qing dynasty used in the casting process from which other mother coins were produced.

- Coin trees (錢樹), are the "tree-shaped" result of the casting process off of which the cash coins were taken to later be strung together.

- Niqian (simplified Chinese: 泥钱; traditional Chinese: 泥錢; pinyin: ní qián) refers to cash coins made out of clay, when the government of the You Zhou Autonomous Region (900–914) confiscated all bronze cash coins and buried them in a cave, because of this the people had to rely on cash coins made out of clay while later bad quality iron cash coins were issued.[57]

- Matched cash coins (對錢, duì qián, 對品, duì pǐn, 和合錢, hé hé qián), is a term introduced during the Southern Tang and started being extensively used during the Northern Song dynasty where cash coins with the same weight, inscription, and denomination was simultaneously cast in different scripts such as regular script and seal script while all having the same legend.

- Bingqian (餅錢, "biscuit coins" or "cake coins"), is a term used by modern Chinese and Taiwanese coin collectors to refer to cash coins that have extremely broad outer rims and are extremely thick and heavy. These cash coins were produced under Emperor Zhenzong during the Song dynasty and bear the inscriptions Xianping Yuanbao (咸平元寶) and Xiangfu Yuanbao (祥符元寶), respectively. Bingqian can range from being 26.5 millimeters in diameter and weighing 10.68 grams to being 66 millimeters in diameter.[58][59][60]

- Zhiqian (制錢, "Standard cash coins"), a term used the Ming and Qing dynasties to refer to copper-alloy cash coins produced by the imperial mints according to the standards which were fixed by the central government.

- Jiuqian (舊錢), a term used during the Ming and Qing dynasties to refer to Song dynasty era cash coins that were still in circulation.

- Siqian (私錢) or Sizhuqian (私鑄錢), refers to cash coins produced by private mints or forgers.[61]

- Yangqian (样錢, "Model coin"), also known as Beiqian (北錢, "Northern coin"), is a term used during the Ming dynasty to refer to full weight (1 qián) and fine quality which were delivered to Beijing as seigniorage revenue.

- Fengqian (俸錢, "Stipend coin"), is a term used during the Ming dynasty to refer to second rate cash coins that had a weight of 0.9 qián and were distributed through the salaries of government officials and emoluments.

- Shangqian (賞錢, "Tip money"), is a term used during the Ming dynasty to refer to cash coins that were small, thin, and very fragile (comparable to Sizhuqian) that were used to pay the wages of employees of the imperial government (including the mint workers themselves) and was one of the most commonly circulating types of cash coins during the Ming dynasty among the general population.[62]

- Woqian (倭錢, "Japanese cash"), refers to Japanese cash coins that entered China during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, the Imperial Chinese court eventually prohibited them. These are sometimes discovered in China among Chinese cash coins.[63][64][65]

- Guangbei qian (光背錢), is a Qing dynasty term that refers to Shunzhi Tongbao (順治通寳) cash coins with no reverse inscriptions including mint marks.

- Xiaoqian (小錢, "small cash") or Qingqian (輕錢), is a Qing dynasty era term that refers to lightweight cash coins created from 1702 that had a weight of 0.7 qián, these coins all disappeared from circulation around the middle of the 18th century.

- Zhongqian (重錢, "full-weight cash" or "heavy cash"), refers to cash coins produced from 1702 with a weight of 1.4 qián and were 1⁄1000 of a tael of silver.

- Huangqian (黃錢, "yellow cash"), a term used to refer to early Qing dynasty era cash coins that didn't contain any tin.

- Qingqian (青錢, "green cash"), is a term used to refer to Qing dynasty era cash coins produced from 1740 where 2% tin was added to the alloy, however despite being called "green cash" it looked indistinguishable from "yellow cash".[66]

- Daqian (大錢, "Big money"), cash coins with a nominal value of 4 wén or higher. This term was used in the Qing dynasty from the Xianfeng period onwards.

- Kuping Qian (庫平錢), refers to a unit that was part of the official standardisation of the Chinese monetary system during the late Qing period by the imperial treasury to create a decimal system in which 1 Kuping Qian was 1⁄1000 of a Kuping tael.

- Huaqian (花錢, "Flower coin"), charms, amulets, and talismans that often resemble cash coins.

- Dongqian (東錢, "Eastern cash"), an exchange rate used for cash coins in the Fengtian province, where only 160 cash coins make up a string.

- Jingqian (京錢, "metropolitan cash") an exchange rate used where only 500 cash coins make up a string.[67]

See also

- History of Chinese currency

- Jiaozi (currency), the earliest paper money

- Economic history of China (pre-1911)

- Economic history of China (1912–1949)

Currencies based on the Chinese cash

References

- ↑ Kann p. 385.

- ↑ Douglas Harper (2001). "Online Etymology Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-04-11.

- ↑ Roberts, Edmund. (1837) Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat: In the U.S. Sloop-of-war Peacock, Harper & Brothers. Harvard University archive. No ISBN Digitized.

- ↑ "The Production Process of Older Chinese Coins。". Admin for Chinesecoins.com (Treasures & Investments). 3 June 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ↑ 2 Click COINS How were ancient Chinese coins made. Retrieved: 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Qi Xiang Tong Bao Engraved Mother Coin". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 24 December 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese Money Trees. - 搖錢樹。". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ↑ G.X. Series Chinese Provinces that issued machine struck coins, from 1900s to 1950s. Last updated: 10 June 2012. Retrieved: 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese "World of Brightness" Coin". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 18 September 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2017.

- ↑ "Home tools as coins in ancient China". John Liang and Sergey Shevtcov for the Chinese Coinage Website (Charm.ru). 11 July 1998. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Fredrik Schöth. Chinese Currency. Revised and edited by Virgil Hancock. Iola, WI, USA: Krause, 1965.

- ↑ Liuliang Yu, Hong Yu, Chinese Coins: Money in History and Society Long River Press, 2004.

- ↑ "[Weekender] Korean currency evolves over millennium". Chang Joowon (The Korean Herald – English Edition). 28 August 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ↑ David Hartill (2011). Early Japanese Coins. New Generation Publishing. ISBN 0755213653

- ↑ "Ryuukyuuan coins". Luke Roberts at the Department of History - University of California at Santa Barbara. 24 October 2003. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ↑ ED. TODA. (1882) ANNAM and its minor currency.

- ↑ Dr. R. Allan Barker. (2004) The historical Cash Coins of Viet Nam. ISBN 981-05-2300-9

- ↑ Dr. Ting Fu-Pao A catalog of Ancient Chinese Coins (including Japan, Korea & Annan) Published: 1 January 1990.

- ↑ Numis' Numismatic Encyclopedia. A reference list of 5000 years of Chinese coinage. (Numista) Written on December 9, 2012 • Last edit: June 13, 2013 Retrieved: 16 June 2017

- ↑ "Sapeque and Sapeque-Like Coins in Cochinchina and Indochina (交趾支那和印度支那穿孔錢幣)". Howard A. Daniel III (The Journal of East Asian Numismatics – Second issue). 20 April 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ↑ The Eduard Kann Collection of Chinese Coins and Odd & Curious Monies, H.D. Gibbs Collection, Part V, and Gold, Silver Rarities of the World: To be Offered at Public Auction Sale, June 18, 19, 20, 1971 Publisher: Schulman Coin & Mint, Inc. Published: 1971

- ↑ Joel’s Coins 2400 Years of Chinese Coins. Retrieved: 13 July 2017.

- ↑ David, Hartill (September 22, 2005). Cast Chinese Coins. Trafford, United Kingdom: Trafford Publishing. p. 431. ISBN 978-1412054669.

- ↑ Wang, Yü-ch'üan: Early Chinese Coinage.

- ↑ Sanford J. Durst, New York 1980. First published 1951.

- ↑ Yang, Lien-sheng: Money and Credit in China, a Short History. Harvard University Press. Cambridge 1971.

- ↑ The Collection Museum An introduction and identification guide to Chinese Qing-dynasty coins. by Qin Cao. Retrieved: 02 July 2017.

- ↑ "Fortune-Telling and Old Chinese Cash Coins. Traditional Methods of Fortune-Telling". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primal Trek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "What To Expect From A Chinese Fortune Teller: A Guide to Prices, Fortune Telling Methods, and More". Lauren Mack (ThoughtCo). 26 February 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese Coins and Traditional Chinese Medicine". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primal Trek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "wiseGEEK: In Traditional Chinese Medicine, what is Coining?". Lixing Lao · Ling Xu · Shifen Xu (wiseGEEK). Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "CAO GIO (Coin Rubbing or Coining) by Lan Pich". Lan Pich (Vanderbilt University School of Medicine). 14 October 2006. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ↑ "Store Signs of Ancient Chinese Coins". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primal Trek – a journey through Chinese culture). 11 September 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ↑ "Chinese Coins and Bank Logos". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primal Trek – a journey through Chinese culture). 10 February 2013. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- ↑ Espos.de (Epical, Prolific, Smart Open Source of Divine Enjoyment) Red Bank of China Logo. Retrieved: 22 July 2017.

- ↑ Australian Museum Kepeng (Chinese coins) Bali, Indonesia. Australian Museum Collection Last update: 27 October 2009. Access date: 03 October 2017.

- ↑ Imexbo.nl, Imexbo.org, Imexbo.eu Chinezen en/in Indië. by Imexbo. Bronnen vermeld door de website (sources named by the reference): Tropenmuseum; KB.nl , Waanders Uitgeverij; Ong Eng Die, Chinezen in Nederlandsch-Indië, Assen 1943; Role of the Indonesian Chinese in Shaping Modern Indonesian Life, Special Issue Indonesia, Cornell Southeast Asia Program, Ithaca New York 1991; James R. Rush, Opium to Java, Revenue Farming and Chinese Enterprise in Colonial Indonesia 1860-1910, Ithaca New York, 1990; Leo Suryadinata, Peranakan Chinese Politics in Java 1917-1942, Singapore 1981; Persoonlijke interviews met enkele Chinese Indonesiërs 2008-2011. Access date: 10 August 2017. (in Dutch)

- ↑ "Body Armor Made of Old Chinese Coins". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 1 February 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ "27. Chinese coins on Tlingit armour". Chinese Money Matters (The British Museum). 11 September 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ "Alaskan Tlingit Body Armor Made of Coins". Everett Millman (Gainesville News – Precious Metal, Financial, and Commodities News). 23 September 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ "Ancient Chinese Coin Brought Good Luck in Yukon". Rossella Lorenzi (for the Discovery Channel) – Hosted on NBC News. 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ "17th-century Chinese coin found in Yukon - Russian traders linked China with First Nations". CBC News. 1 November 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ↑ Department of Economic History - London School of Economics Money and Monetary System in China in 19-20th Century: an Overview by Debin Ma. Economic History Department London School of Economics Dec. 2011 Chapter contribution to Encyclopedia of Financial Globalization edited by Charles Calomiris and Larry Neal forthcoming with Elsevier. Published: January 2012. Retrieved: 05 February 2018.

- ↑ Lloyd Eastman, Family, Fields, and Ancestors: Constancy and Change in China's Social and Economic History, 1550-1949, Oxford University Press (1988), 108-112.

- ↑ Village Life in China: A study in sociology door Arthur H. Smith, D.D. New York, Chicago, Toronto. Uitgever: Fleming H. Revell Company (Publishers of Evangelical Literature) Auteursrecht: 1899 door Fleming H. Revell Company

- ↑ Wang Yü-Ch’üan, Early Chinese coinage, The American numismatic society, New York, 1951.

- ↑ "Stringing Cash Coins". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primal Trek – a journey through Chinese culture). 28 September 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- ↑ Guttag’s Foreign Currency and Exchange Guide (1921) Uitgegever: Guttag Bros. Numismatics New York, U.S.A. Accessed: 3 October 2017.

- ↑ Chinesecoins.lyq.dk Weights and units in Chinese coinage Section: “Guan 貫, Suo 索, Min 緡, Diao 吊, Chuan 串.” by Lars Bo Christensen. Retrieved: 05 February 2018.

- ↑ The Mahjong Tile Set From Cards to Tiles: The Origin of Mahjong(g)’s Earliest Suit Names by Michael Stanwick and Hongbing Xu. Retrieved: 5 February 2018.

- ↑ "Chinese Coins with Flower (Rosette) Holes - 花穿錢。". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 16 November 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ↑ Calgary Coins and Antiques Gallery – Cast Chinese Coins - MEDIEVAL CHINESE COINS - TARTAR, MONGOL, MING DYNASTIES (A.D. 960 to 1644). Retrieved: 01 July 2018.

- ↑ Anything Anywhere China, amulets by Bob Reis. Retrieved: 01 July 2018.

- ↑ 中國大百科全書(中國歷史), 中國大百科全書出版社 1994, ISBN 7-5000-5469-6. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ↑ 中國歷代幣貨 A History of Chinese Currency (16th Century BC - 20th Century AD), 1983 Jointly Published by Xinhua (New China) Publishing House N.C.N. Limited M.A.O. Management Group Ltd. ISBN 962 7094 01 3. (in Mandarin Chinese).

- ↑ The Náprstek museum XINJIANG CAST CASH IN THE COLLECTION OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM, PRAGUE. by Ondřej Klimeš (ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 25 • PRAGUE 2004). Retrieved: 28 August 2018.

- ↑ 大洋网-广州日报 (25 March 2015). "五代十国钱币制度混乱 甚至出现 "泥钱"" (in Chinese). Sina Corp. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ↑ "Song Dynasty Biscuit Coins". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 15 February 2016. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- ↑ Data.Shouxi.com - Lot:412 北宋特大型“咸平元宝”饼钱 - 进入专场。Retrieved: 17 September 2018. (in Mandarin Chinese written in Simplified Chinese characters)

- ↑ Taiwan Note - 古錢 - 最新更動日期: 2016/12/17. Retrieved: 17 September 2018. (in Mandarin Chinese written in Traditional Chinese characters)

- ↑ "zhiqian 制錢, standard cash". By Ulrich Theobald (Chinaknowledge). 25 May 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ↑ Hartill 2005, p. 237.

- ↑ "Young Numismatists in China". Gary Ashkenazy / גארי אשכנזי (Primaltrek – a journey through Chinese culture). 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ AS谈古论今 (15 September 2015). "农妇上山拾柴意外发现千枚古钱币 价值高达数百万" (in Chinese). Sohu, Inc. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ↑ Guiyang Evening News (guiyang wanbao, 贵阳晚报). Published: August 12th, 2015. (in Mandarin Chinese written in Simplified Chinese characters)

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald (13 April 2016). "Qing Period Money". Chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald (13 April 2016). "Qing Period Paper Money". Chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

![]()

.jpg)