Cockayne syndrome

| Cockayne syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Specialty |

Medical genetics |

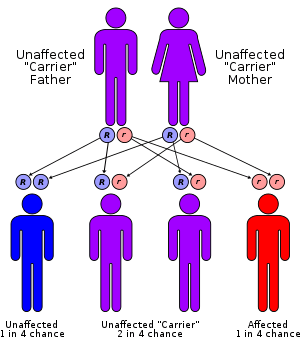

Cockayne syndrome (CS), also called Neill-Dingwall syndrome, is a rare and fatal autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by growth failure, impaired development of the nervous system, abnormal sensitivity to sunlight (photosensitivity), eye disorders and premature aging.[1][2][3] Failure to thrive and neurological disorders are criteria for diagnosis, while photosensitivity, hearing loss, eye abnormalities, and cavities are other very common features.[3] Problems with any or all of the internal organs are possible. It is associated with a group of disorders called leukodystrophies, which are conditions characterized by degradation of neurological white matter. The underlying disorder is a defect in a DNA repair mechanism.[4] Unlike other defects of DNA repair, patients with CS are not predisposed to cancer or infection.[5] Cockayne syndrome is a rare but destructive disease usually resulting in death within the first or second decade of life. The mutation of specific genes in Cockayne syndrome is known, but the widespread effects and its relationship with DNA repair is yet to be well understood.[5]

It is named after English physician Edward Alfred Cockayne (1880–1956) who first described it in 1936 and re-described in 1946.[6] Neill-Dingwall syndrome was named after Mary M. Dingwall and Catherine A. Neill.[6] These two scientists described the case of two brothers with Cockayne syndrome and asserted it was the same disease described by Cockayne. In their article the two contributed to the symptoms of the disease through their discovery of calcifications in the brain. They also compared Cockayne syndrome to what is now known as Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS), then called progeria, due to the advanced aging that characterizes both disorders.[6]

Genetics

Cockayne syndrome is classified genetically as follows:

| Type | OMIM | Gene |

|---|---|---|

| A | 216400 | ERCC8 (also called CSA) |

| B | 133540 | ERCC6 (also called CSB) |

| C | 216411 | none known |

Mutations in the ERCC8 (also known as CSA) gene or the ERCC6 (also known as CSB) gene are the cause of Cockayne syndrome.[7] Mutations in the ERCC6 gene mutation makes up ~70% of cases. The proteins made by these genes are involved in repairing damaged DNA via the transcription-coupled repair mechanism, particularly the DNA in active genes. DNA damage is caused by ultraviolet rays from sunlight, radiation, or free radicals in the body. A normal cell can repair damage to DNA easily before it collects. If either the ERCC6 or the ERCC8 gene is altered (as in Cockayne Syndrome), DNA damage is not repaired. As this damage accumulates, it can lead to malfunctioning cells or cell death. This cell death and malfunctioning likely contributes to the symptoms of Cockayne Syndrome such as premature aging and hypomyelination of neurons.[7]

DNA repair

In contrast to cells with normal repair capability, CSA and CSB deficient cells are unable to preferentially repair cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers induced by the action of ultraviolet (UV) light on the template strand of actively transcribed genes.[8] This deficiency reflects the loss of ability to perform the DNA repair process known as transcription coupled nucleotide excision repair (TC-NER).

Within the damaged cell, the CSA protein normally localizes to sites of DNA damage, particularly inter-strand cross-links, double-strand breaks and some monoadducts.[9] CSB protein is also normally recruited to DNA damaged sites, and its recruitment is most rapid and robust as follows: interstrand crosslinks > double-strand breaks > monoadducts > oxidative damages.[9] CSB protein forms a complex with another DNA repair protein, SNM1A(DCLRE1A), a 5’ – 3’ exonuclease, that localizes to inter-strand cross-links in a transcription dependent manner.[10] The accumulation of CSB protein at sites of DNA double-strand breaks occurs in a transcription dependent manner and facilitates homologous recombinational repair of the breaks.[11] During the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, DNA damage can trigger a CSB-dependent recombinational repair process that uses an RNA (rather than DNA) template.[12]

The premature aging features of CS are likely due, at least in part, to the deficiencies in DNA repair (see DNA damage theory of aging).

Diagnosis

Persons with this syndrome have smaller than normal head sizes (microcephaly), are of short stature (dwarfism), their eyes appear sunken, and they have an "aged" look. They often have long limbs with joint contractures (inability to relax muscle at a joint), a hunched back (kyphosis), and they may be very thin (cachetic), due to a loss of subcutaneous fat. Their small chin, large ears, and pointy, thin nose often give an aged appearance.[13] The skin of those with Cockayne syndrome is also frequently affected. Hyperpigmentation, varicose or spider veins (telangiectasia),[13] and serious sensitivity to sunlight are common, even in individuals without XP-CS. Often patients with Cockayne Syndrome will severely burn or blister with very little exposure. The eyes of patients can be affected in various ways and eye abnormalities are common in CS. Cataracts and cloudiness of the cornea (corneal opacity) are common. The loss of and damage to nerves of the optic nerve, causing optic atrophy can occur.[3] Nystagmus, or involuntary eye movement, and pupils that fail to dilate demonstrate a loss of control of voluntary and involuntary muscle movement.[13] A salt and pepper retinal pigmentation is also a visible symptom. Diagnosis is determined by a specific test for DNA repair, which measures the recovery of RNA after exposure to UV radiation. Despite being associated with genes involved in nucleotide excision repair (NER), unlike xeroderma pigmentosum, CS is not associated with an increased risk of cancer.[5]

Neurology

Imaging studies reveal widespread absence of the myelin sheaths of the neurons in the white matter of the brain, and general atrophy of the cortex.[5] Calcifications have also been found in the putamen, an area of the forebrain that regulates movements and aids in some forms of learning,[13] along with in the cortex.[6] Additionally, atrophy of the central area of the cerebellum found in patients with Cockayne syndrome could also result in the lack of muscle control, particularly involuntary, and poor posture typically seen.

Types

- CS Type I, the "classic" form, is characterized by normal fetal growth with the onset of abnormalities in the first two years of life. Vision and hearing gradually decline.[7] The central and peripheral nervous systems progressively degenerate until death in the first or second decade of life as a result of serious neurological degradation. Cortical atrophy is less severe in CS Type I.[13]

- CS Type II is present from birth (congenital) and is much more severe than CS Type 1.[7] It involves very little neurological development after birth. Death usually occurs by age seven. This specific type has also been designated as cerebro-oculo-facio-skeletal (COFS) syndrome or Pena-Shokeir syndrome Type II.[7] COFS syndrome is named so due to the effects it has on the brain, eyes, face, and skeletal system, as the disease frequently causes brain atrophy, cataracts, loss of fat in the face, and osteoporosis. COFS syndrome can be further subdivided into several conditions (COFS types 1, 2, 3 (associated with xeroderma pigmentosum) and 4).[14] Typically patients with this early-onset form of the disorder show more severe brain damage, including reduced myelination of white matter, and more widespread calcifications, including in the cortex and basal ganglia.[13]

- CS Type III, characterized by late onset, is typically milder than Types I and II.[7] Often patients with Type III will live into adulthood.

- Xeroderma pigmentosum-Cockayne syndrome (XP-CS) occurs when an individual also suffers from xeroderma pigmentosum, another DNA repair disease. Some symptoms of each disease are expressed. For instance, freckling and pigment abnormalities characteristic of XP are present. The neurological disorder, spasticity, and underdevelopment of sexual organs characteristic of CS are seen. However, hypomyelination and the facial features of typical CS patients are not present.[15]

Treatment

There is no permanent cure for this syndrome, although patients can be treated according to their specific symptoms. The prognosis for those with Cockayne syndrome is poor, as death typically occurs by the age of 12. Treatment usually involves physical therapy and minor surgeries to the affected organs, like cataract removal.[3] Also wearing high-factor sunscreen and protective clothing is recommended as patients with Cockayne syndrome are very sensitive to UV radiation.[16] Optimal nutrition can also help. Genetic counseling for the parents is recommended, as the disorder has a 25% chance of being passed to any future children, and prenatal testing is also a possibility.[3] Another important aspect is prevention of recurrence of CS in other siblings. Identification of gene defects involved makes it possible to offer genetic counseling and antenatal diagnostic testing to the parents who already have one affected child.[17]

See also

- Accelerated aging disease

- Biogerontology

- Degenerative disease

- Genetic disorder

- CAMFAK syndrome — thought to be a form (or subset) of Cockayne syndrome[18]

References

- ↑ Bertola,; Cao, H; Albano, Lm; Oliveira, Dp; Kok, F; Marques-Dias, Mj; Kim, Ca; Hegele, Ra (2006). "Cockayne syndrome type A: novel mutations in eight typical patients". Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (8): 701–5. doi:10.1007/s10038-006-0011-7. PMID 16865293.

- ↑ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology (10th ed.). Saunders. p. 575. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bender M, Potocki L, Metry D. What syndrome is this? Cockayne syndrome. Pediatric Dermatology [serial online]. November 2003;20(6):538-540. Available from: MEDLINE with Full Text, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Hoeijmakers JH (October 2009). "DNA damage, aging, and cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (15): 1475–85. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0804615. PMID 19812404.

- 1 2 3 4 Nance M, Berry S (1 January 1992). "Cockayne syndrome: review of 140 cases". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 42 (1): 68–84. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320420115. PMID 1308368.

- 1 2 3 4 Neill CA, Dingwall MM. A Syndrome Resembling Progeria: A Review of Two Cases. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1950;25(123):213-223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cockayne Syndrome. Genetics Home Reference http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/cockayne-syndrome Published April 28, 2015. Reviewed May 2010. Accessed April 30, 2015.

- ↑ van Hoffen A, Natarajan AT, Mayne LV, van Zeeland AA, Mullenders LH, Venema J (1993). "Deficient repair of the transcribed strand of active genes in Cockayne's syndrome cells". Nucleic Acids Res. 21 (25): 5890–5. doi:10.1093/nar/21.25.5890. PMC 310470. PMID 8290349.

- 1 2 Iyama T, Wilson DM (2016). "Elements That Regulate the DNA Damage Response of Proteins Defective in Cockayne Syndrome". J. Mol. Biol. 428 (1): 62–78. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.020. PMC 4738086. PMID 26616585.

- ↑ Iyama T, Lee SY, Berquist BR, Gileadi O, Bohr VA, Seidman MM, McHugh PJ, Wilson DM (2015). "CSB interacts with SNM1A and promotes DNA interstrand crosslink processing". Nucleic Acids Res. 43 (1): 247–58. doi:10.1093/nar/gku1279. PMC 4288174. PMID 25505141.

- ↑ Batenburg NL, Thompson EL, Hendrickson EA, Zhu XD (2015). "Cockayne syndrome group B protein regulates DNA double-strand break repair and checkpoint activation". EMBO J. 34 (10): 1399–416. doi:10.15252/embj.201490041. PMC 4491999. PMID 25820262.

- ↑ Wei L, Nakajima S, Böhm S, Bernstein KA, Shen Z, Tsang M, Levine AS, Lan L (2015). "DNA damage during the G0/G1 phase triggers RNA-templated, Cockayne syndrome B-dependent homologous recombination". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (27): E3495–504. doi:10.1073/pnas.1507105112. PMC 4500203. PMID 26100862.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Javadzadeh M. Cockayne Syndrome. Iran J Child Neurol. Autumn 2014;8;4(Suppl.1):18-19.

- ↑ Cerebrooculofacioskeletal Syndrome 2. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. https://omim.org/entry/610756. Published 2/12/2007.

- ↑ Laugel V. Cockayne Syndrome. 2000 Dec 28 [Updated 2012 Jun 14]. In: Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2015. Available from:

- ↑ Kyllermen, Marten. Cockayne Syndrome. Swedish Information Centre for Rare Diseases. 2012: 4.0. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/rarediseases/cockaynesyndrome#anchor_17

- ↑ Title: Cockayne Syndrome Authors: Dr Nita R Sutay, Dr Md Ashfaque Tinmaswala, Dr Manjiri Karlekar, Dr Swati Jhahttp://jmscr.igmpublication.org/v3-i7/35%20jmscr.pdf

- ↑ http://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/OC_Exp.php?Lng=GB&Expert=1317

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- 'Amy and Friends' — a friendly charity based in the UK supporting children with Cockayne Syndrome

- Share and Care Cockayne Syndrome Network

- cockayne at NIH/UW GeneTests

- This article incorporates some public domain text from The U.S. National Library of Medicine