Microcephaly

| Microcephaly | |

|---|---|

| |

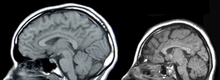

| A baby with microcephaly (left) compared to a baby with a typical head size | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics, Psychiatry, Neurology |

Microcephaly is a medical condition in which the brain does not develop properly resulting in a smaller than normal head.[1] Microcephaly may be present at birth or it may develop in the first few years of life.[1] Often people with the disorder have an intellectual disability, poor motor function, poor speech, abnormal facial features, seizures, and dwarfism.[1]

The disorder may stem from a wide variety of conditions that cause abnormal growth of the brain, or from syndromes associated with chromosomal abnormalities. A homozygous mutation in one of the microcephalin genes causes primary microcephaly.[2][3] It serves as an important neurological indication or warning sign, but no uniformity exists in its definition. It is usually defined as a head circumference (HC) more than two standard deviations below the mean for age and sex.[4][5] Some academics advocate defining it as head circumference more than three standard deviations below the mean for the age and sex.[6]

There is no specific treatment that returns the head size to normal.[1] In general, life expectancy for individuals with microcephaly is reduced and the prognosis for normal brain function is poor. Occasionally, some will grow normally and develop normal intelligence.[1]

Signs and symptoms

Affected newborns generally have striking neurological defects and seizures. Severely impaired intellectual development is common, but disturbances in motor functions may not appear until later in life.

Infants with microcephaly are born with either a normal or reduced head size. Subsequently, the head fails to grow, while the face continues to develop at a normal rate, producing a child with a small head and a receding forehead, and a loose, often wrinkled scalp. As the child grows older, the smallness of the skull becomes more obvious, although the entire body also is often underweight and dwarfed. Development of motor functions and speech may be delayed. Hyperactivity and intellectual disability are common occurrences, although the degree of each varies. Convulsions may also occur. Motor ability varies, ranging from clumsiness in some to spastic quadriplegia in others.

Causes

Microcephaly is a type of cephalic disorder. It has been classified in two types based on the onset:[7]

Congenital

Isolated

- Familial (autosomal recessive) microcephaly

- Autosomal dominant microcephaly

- X-linked microcephaly

- Chromosomal (balanced rearrangements and ring chromosome)

Syndromes

- Chromosomal

- Poland syndrome

- Down syndrome

- Edward syndrome

- Patau syndrome

- Unbalanced rearrangements

- Contiguous gene deletion

- 4p deletion (Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome)

- 5p deletion (Cri-du-chat)

- 7q11.23 deletion (Williams syndrome)

- 22q11 deletion (DiGeorge syndrome)

- Single gene defects

- Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome

- Seckel syndrome

- Cornelia de Lange syndrome

- Holoprosencephaly

- Primary microcephaly 4[8]

- Wiedemann-Steiner syndrome

Acquired

- Disruptive injuries

- Ischemic stroke

- Hemorrhagic stroke

- Death of a monozygotic twin

- Congenital cytomegalovirus infection

- Toxoplasmosis

- Congenital rubella syndrome

- Zika virus (see Zika fever#Microcephaly) [9]

- Drugs

Other

- Radiation exposure to mother

- Maternal malnutrition

- Maternal phenylketonuria

- Poorly controlled gestational diabetes

- Hyperthermia

- Maternal hypothyroidism

- Placental insufficiency

Postnatal onset

Genetic

- Inborn errors of metabolism

- Congenital disorder of glycosylation

- Mitochondrial disorders

- Peroxisomal disorder

- Glucose transporter defect

- Menkes disease

- Congenital disorders of amino acid metabolism

- Organic acidemia

Syndromes

- Contiguous gene deletion

- 17p13.3 deletion (Miller–Dieker syndrome)

- Single gene defects

- Rett syndrome (primarily girls)

- Nijmegen breakage syndrome

- X-linked lissencephaly with abnormal genitalia

- Aicardi–Goutières syndrome

- Ataxia telangiectasia

- Cohen syndrome

- Cockayne syndrome

Acquired

- Disruptive injuries

- Infections

- Congenital HIV encephalopathy

- Meningitis

- Encephalitis

- Toxins

- Deprivation

Genetic factors may play a role in causing some cases of microcephaly. Relationships have been found between autism, duplications of chromosomes, and macrocephaly on one side. On the other side, a relationship has been found between schizophrenia, deletions of chromosomes, and microcephaly.[10][11][12] Moreover, an association has been established between common genetic variants within known microcephaly genes (MCPH1, CDK5RAP2) and normal variation in brain structure as measured with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—i.e., primarily brain cortical surface area and total brain volume.[13]

The spread of Aedes mosquito-borne Zika virus has been implicated in increasing levels of congenital microcephaly by the International Society for Infectious Diseases and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[14] Zika can spread from a pregnant woman to her fetus. This can result in other severe brain malformations and birth defects.[15][16][17][18] A study published in The New England Journal of Medicine has documented a case in which they found evidence of the Zika virus in the brain of a fetus that displayed the morphology of microcephaly.[19]

Microencephaly

"Microcephaly" means "smallheadedness" (New Latin microcephalia, from Ancient Greek μικρός mikrós "small" and κεφαλή kephalé "headed"[20]). However, the older, slightly more traditional classification, "microencephaly," translates to, "smallness of brain." Similar to various sociocultural updates in linguistics, the term is deemed obsolete by modern medical culture. Therefore, because the size of the brain is most often determined by the size of one's skull, the use of classifying, "microencephaly," in more modern literature, is today almost always implied when discussing cases wherein microcephaly manifests.[21]

Microlissencephaly

Microlissencephaly is microcephaly combined with lissencephaly (smooth brain surface due to absent sulci and gyri). Most cases of microlissencephaly are described in consanguineous families, suggesting an autosomal recessive inheritance.[22][23][24]

Other

After the dropping of atomic bombs "Little Boy" on Hiroshima and "Fat Man" on Nagasaki, several women close to ground zero who had been pregnant at the time gave birth to children with microcephaly.[25] Microcephaly prevalence was seven of a group of 11 pregnant women at 11–17 weeks of gestation who survived the blast at less than 1.2 km (0.75 mi) from ground zero. Due to their proximity to the bomb, the pregnant women's in utero children received a biologically significant radiation dose that was relatively high due to the massive neutron output of the lower explosive-yielding Little Boy.[26] Microcephaly is the only proven malformation, or congenital abnormality, found in the children of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[26]

Other relations

Intracranial volume also affects this pathology, as it is related with the size of the brain.[27]

Pathophysiology

Microcephaly generally is due to the diminished size of the largest part of the human brain, the cerebral cortex, and the condition can arise during embryonic and fetal development due to insufficient neural stem cell proliferation, impaired or premature neurogenesis, the death of neural stem cells or neurons, or a combination of these factors.[28] Research in animal models such as rodents has found many genes that are required for normal brain growth. For example, the Notch pathway genes regulate the balance between stem cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the stem cell layer known as the ventricular zone, and experimental mutations of many genes can cause microcephaly in mice,[29] similar to human microcephaly.[30][31] Mutations of the abnormal spindle-like microcephaly-associated (ASPM) gene are associated with microcephaly in humans and a knockout model has been developed in ferrets that exhibits severe microcephaly. [32] In addition, viruses such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) or Zika have been shown to infect and kill the primary stem cell of the brain—the radial glial cell, resulting in the loss of future daughter neurons.[33][34] The severity of the condition may depend on the timing of infection during pregnancy.

Treatment

There is no known cure for microcephaly.[1] Treatment is symptomatic and supportive.[1]

History

People with microcephaly were sometimes sold to freak shows in North America and Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, where they were known by the name "pinheads". Many of them were presented as different species (e.g., "monkey man") and described as being the missing link.[35] Famous examples include Zip the Pinhead (although he may not have had microcephaly)[36] and Schlitzie the Pinhead,[36] who also starred in the 1932 film Freaks. Both men were cited as influences on the development of the long-running comic strip character Zippy the Pinhead, created by Bill Griffith.[37]

Notable cases

- A certain 'dwarf' of Punt (ancient Somalia) was given by the Chief clans as partial tribute to the last ruler of Ancient Egypt’s Old Kingdom, Pepi II Neferkare (6th Dynasty (circa 2125-2080 B.C.E.); it could be inferred that this person was indeed, also microcephalic. In a letter preserved at the British Museum, the young king gives instructions by letter, ”Harkhuf! The men in your service {escorts; soldiers; sailors; guards, etc.} ought pay sincere care with the dwarf’s head while sleeping during the voyage to the palace“ (so that it doesn't fall off...). At the same time, it could be for other reasons unrelated to microcephaly, etc.[38]

- Triboulet, a jester of duke René of Anjou (not to be confused with the slightly later Triboulet at the French court).

- Jenny Lee Snow and Elvira Snow, whose stage names were Pip and Zip, respectively, were sisters with microcephaly who acted in the 1932 film Freaks.

- Schlitze "Schlitzie" Surtees, possibly born Simon Metz, was a sideshow performer and actor.

- Lester "Beetlejuice" Green, a member of radio host Howard Stern's Wack Pack.

See also

- Anencephaly (Usually rapidly fatal)

- Cerebral rubicon

- Hydrocephaly

- Macrocephaly

- Seckel syndrome

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "NINDS Microcephaly Information Page". NINDS. June 30, 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ↑ Jackson, Andrew P.; Eastwood, Helen; Bell, Sandra M.; Adu, Jimi; Toomes, Carmel; Carr, Ian M.; Roberts, Emma; Hampshire, Daniel J.; et al. (2002). "Identification of Microcephalin, a Protein Implicated in Determining the Size of the Human Brain". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 71 (1): 136–42. doi:10.1086/341283. PMC 419993. PMID 12046007.

- ↑ Jackson, Andrew P.; McHale, Duncan P.; Campbell, David A.; Jafri, Hussain; Rashid, Yasmin; Mannan, Jovaria; Karbani, Gulshan; Corry, Peter; et al. (1998). "Primary Autosomal Recessive Microcephaly (MCPH1) Maps to Chromosome 8p22-pter". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 63 (2): 541–6. doi:10.1086/301966. PMC 1377307. PMID 9683597.

- ↑ Leviton, A.; Holmes, L. B.; Allred, E. N.; Vargas, J. (2002). "Methodologic issues in epidemiologic studies of congenital microcephaly". Early Hum Dev. 69 (1): 91–105. doi:10.1016/S0378-3782(02)00065-8.

- ↑ Opitz, J. M.; Holt, M. C. (1990). "Microcephaly: general considerations and aids to nosology". J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol. 10 (2): 75–204. PMID 2211965.

- ↑ Behrman, R. E.; Kligman, R. M.; Jensen, H. B. (2000). Nelson's Textbook of Pediatrics (16th ed.). Philadelphia: WB Saunders. ISBN 0721677673.

- ↑ Ashwal, S.; Michelson, D.; Plawner, L.; Dobyns, W. B. (2009). "Practice Parameter: Evaluation of the child with microcephaly (an evidence-based review)". Neurology. 73 (11): 887–897. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b783f7. PMC 2744281.

- ↑ Szczepanski, Sandra; Hussain, Muhammad Sajid; Sur, Ilknur; Altmüller, Janine; Thiele, Holger; Abdullah, Uzma; Waseem, Syeda Seema; Moawia, Abubakar; Nürnberg, Gudrun; Noegel, Angelika Anna; Baig, Shahid Mahmood; Nürnberg, Peter (30 November 2015). "A novel homozygous splicing mutation of CASC5 causes primary microcephaly in a large Pakistani family". Human Genetics. 135 (2): 157–170. doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1619-5. PMID 26621532.

- ↑ Emily E. Petersen; Erin Staples; Dana Meaney-Delman; Marc Fischer; Sascha R. Ellington; William M. Callaghan; Denise J. Jamieson (January 22, 2016). "Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak — United States, 2016". www.cdc.gov/mmwr. MMWR Early Release on the MMWR website. pp. 30–33. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017.

- ↑ Crespi B, Stead P, Elliot M; Stead; Elliot (January 2010). "Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (Suppl 1): 1736–41. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.1736C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906080106. PMC 2868282. PMID 19955444. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21.

- ↑ Stone, Jennifer L.; o’Donovan, Michael C.; Gurling, Hugh; Kirov, George K.; Blackwood, Douglas H. R.; Corvin, Aiden; Craddock, Nick J.; Gill, Michael; Hultman, Christina M.; Lichtenstein, Paul; McQuillin, Andrew; Pato, Carlos N.; Ruderfer, Douglas M.; Owen, Michael J.; St Clair, David; Sullivan, Patrick F.; Sklar, Pamela; Purcell (Leader), Shaun M.; Stone, Jennifer L.; Ruderfer, Douglas M.; Korn, Joshua; Kirov, George K.; MacGregor, Stuart; McQuillin, Andrew; Morris, Derek W.; O’Dushlaine, Colm T.; Daly, Mark J.; Visscher, Peter M.; Holmans, Peter A.; et al. (September 2008). "Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia". Nature. 455 (7210): 237–41. Bibcode:2008Natur.455..237S. doi:10.1038/nature07239. PMC 3912847. PMID 18668038.

- ↑ Dumas L, Sikela JM (2009). "DUF1220 domains, cognitive disease, and human brain evolution". Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 74: 375–82. doi:10.1101/sqb.2009.74.025. PMC 2902282. PMID 19850849.

- ↑ Rimol, Lars M.; Agartz, Ingrid; Djurovic, Srdjan; Brown, Andrew A.; Roddey, J. Cooper; Kahler, Anna K.; Mattingsdal, Morten; Athanasiu, Lavinia; et al. (2010). "Sex-dependent association of common variants of microcephaly genes with brain structure". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (1): 384–8. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107..384R. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908454107. JSTOR 40536283. PMC 2806758. PMID 20080800.

- ↑ "Zika virus - Brazil: confirmed Archive Number: 20150519.3370768". Pro-MED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. Archived from the original on 2016-01-30.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Sonja A.; Jamieson, Denise J.; Honein, Margaret A.; Petersen, Lyle R. (13 April 2016). "Zika Virus and Birth Defects — Reviewing the Evidence for Causality". New England Journal of Medicine. 374: 1981–1987. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1604338. PMID 27074377. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ "CDC Concludes Zika Causes Microcephaly and Other Birth Defects". CDC. 13 April 2016. Archived from the original on 31 May 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ "CDC issues interim travel guidance related to Zika virus for 14 Countries and Territories in Central and South America and the Caribbean". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016-01-15. Archived from the original on 2016-01-18. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ↑ Beth Mole (2016-01-17). "CDC issues travel advisory for 14 countries with alarming viral outbreaks]". Ars Technica. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 2016-01-18. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- ↑ Mlakar, Jernej; Korva, Misa; Tul, Nataša; Popović, Mara; Poljšak-Prijatelj, Mateja; Mraz, Jerica; Kolenc, Marko; Resman Rus, Katarina; Vesnaver Vipotnik, Tina (2016-03-10). "Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (10): 951–958. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1600651. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 26862926.

- ↑ "Microcephaly - Definition of Microcephaly by Merriam-Webster". Archived from the original on 2014-09-14.

- ↑ David D. Weaver; Ira K. Brandt (1999). Catalog of prenatally diagnosed conditions. JHU Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8018-6044-7. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ↑ Cavallin, Mara; Rujano, Maria A.; Bednarek, Nathalie; Medina-Cano, Daniel; Bernabe Gelot, Antoinette; Drunat, Severine; Maillard, Camille; Garfa-Traore, Meriem; Bole, Christine (2017-10-01). "WDR81 mutations cause extreme microcephaly and impair mitotic progression in human fibroblasts and Drosophila neural stem cells". Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 140 (10): 2597–2609. doi:10.1093/brain/awx218. ISSN 1460-2156. PMID 28969387.

- ↑ Coley, Brian D. (2013-05-21). Caffey's Pediatric Diagnostic Imaging E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 1455753602. Archived from the original on 2017-10-27.

- ↑ Martin, Richard J.; Fanaroff, Avroy A.; Walsh, Michele C. (2014-08-20). Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine E-Book: Diseases of the Fetus and Infant. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323295376. Archived from the original on 2017-10-27.

- ↑ "Aftereffects". Archived from the original on 2009-05-25.

- 1 2 "Teratology in the Twentieth Century Plus Ten".

- ↑ Adams, Hieab H H; Hibar, Derrek P; Chouraki, Vincent; Stein, Jason L; Nyquist, Paul A; Rentería, Miguel E; Trompet, Stella; Arias-Vasquez, Alejandro; Seshadri, Sudha. "Novel genetic loci underlying human intracranial volume identified through genome-wide association". Nature Neuroscience. 19 (12): 1569–1582. doi:10.1038/nn.4398. PMC 5227112. PMID 27694991.

- ↑ Jamuar, SS; Walsh, CA (June 2015). "Genomic variants and variations in malformations of cortical development". Pediatric clinics of North America. 62 (3): 571–85. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2015.03.002. PMC 4449454. PMID 26022163.

- ↑ Rash, BG; Lim, HD; Breunig, JJ; Vaccarino, FM (26 October 2011). "FGF signaling expands embryonic cortical surface area by regulating Notch-dependent neurogenesis". The Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (43): 15604–17. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.4439-11.2011. PMC 3235689. PMID 22031906.

- ↑ Shen, J; Gilmore, EC; Marshall, CA; Haddadin, M; Reynolds, JJ; Eyaid, W; Bodell, A; Barry, B; Gleason, D; Allen, K; Ganesh, VS; Chang, BS; Grix, A; Hill, RS; Topcu, M; Caldecott, KW; Barkovich, AJ; Walsh, CA (March 2010). "Mutations in PNKP cause microcephaly, seizures and defects in DNA repair". Nature Genetics. 42 (3): 245–9. doi:10.1038/ng.526. PMC 2835984. PMID 20118933.

- ↑ Alkuraya, FS; Cai, X; Emery, C; Mochida, GH; Al-Dosari, MS; Felie, JM; Hill, RS; Barry, BJ; Partlow, JN; Gascon, GG; Kentab, A; Jan, M; Shaheen, R; Feng, Y; Walsh, CA (13 May 2011). "Human mutations in NDE1 cause extreme microcephaly with lissencephaly [corrected]". American Journal of Human Genetics. 88 (5): 536–47. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.04.003. PMC 3146728. PMID 21529751.

- ↑ Johnson, Matthew B.; Sun, Xingshen; Kodani, Andrew; Borges-Monroy, Rebeca; Girskis, Kelly M.; Ryu, Steven C.; Wang, Peter P.; Patel, Komal; Gonzalez, Dilenny M.; Woo, Yu Mi; Yan, Ziying; Liang, Bo; Smith, Richard S.; Chatterjee, Manavi; Coman, Daniel; Papademetris, Xenophon; Staib, Lawrence H.; Hyder, Fahmeed; Mandeville, Joseph B.; Grant, P. Ellen; Im, Kiho; Kwak, Hojoong; Engelhardt, John F.; Walsh, Christopher A.; Bae, Byoung-Il (2018). "Aspm knockout ferret reveals an evolutionary mechanism governing cerebral cortical size". Nature. 556 (7701): 370–375. Bibcode:2018Natur.556..370J. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0035-0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ↑ Nowakowski, TJ; Pollen, AA; Di Lullo, E; Sandoval-Espinosa, C; Bershteyn, M; Kriegstein, AR (5 May 2016). "Expression Analysis Highlights AXL as a Candidate Zika Virus Entry Receptor in Neural Stem Cells". Cell stem cell. 18 (5): 591–6. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.012. PMID 27038591.

- ↑ Li, C; Xu, D; Ye, Q; Hong, S; Jiang, Y; Liu, X; Zhang, N; Shi, L; Qin, CF; Xu, Z (7 July 2016). "Zika Virus Disrupts Neural Progenitor Development and Leads to Microcephaly in Mice". Cell stem cell. 19 (1): 120–6. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.017. PMID 27179424.

- ↑ Mateen FJ, Boes CJ (2010). "'Pinheads': the exhibition of neurologic disorders at 'The Greatest Show on Earth'". Neurology. 75 (22): 2028–32. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ff9636. PMID 21115959.

- 1 2 ""Zip the Pinhead: What is it?". The Human Marvels. 16 October 2010. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016.

- ↑ Interview with Bill Griffith, Goblin Magazine 1995 Archived 2012-01-31 at the Wayback Machine., transcribed on zippythepinhead.com; accessed Feb. 13, 2013

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-05-17. Retrieved 2018-02-17.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|